You just started learning Japanese. You're cruising through your beginner kanji list nice and easy.

木. Hey, a tree! 山. Hey, a mountain! Heck yeah, this is easy! The characters even sort of look like trees and mountains.

But then you look at the pronunciations… wait. Why are there two ways to read 木? Is it もく or is it き? Do I read 山 as さん or やま? Which one should I use? Why can this one be read ten possible ways? Who did this and where are they hiding?!

However, it's too late. You're here, and there's no way home. Welcome… to Kanji Park.

The readings (on'yomi and kun'yomi) of kanji are very complicated. At least, that's what many people will tell you. It's kind of true, but it doesn't have to be this way. Figuring out what to learn and when to use which kanji reading is a lot simpler than everyone makes it out to be.

We're going to show you how to do this so you can apply it to your own kanji studies. Kanji will make more sense, and you'll be able to focus on what's actually important: learning how to read Japanese.

Prerequisite: By the way, this article is going to use hiragana, one of Japan's two phonetic alphabets, so if you don't know it yet, if you're a little iffy, or if you just want a refresher, take a look at our hiragana guide first. It usually only takes a day or two (with the help of mnemonics) to get it down pat.

- First, Some History

- Two Kanji Readings for the Price of One

- Single Reading Exceptions

- Why Are There So Many Kanji Readings?

- Romance of the Three Language Shifts

- Multiple Kun'yomi Readings

- How Can I Know the Reading?

- How To Learn Kanji Readings

- Next Steps to Learning Kanji

Before you read any further: we also recorded a podcast on on'yomi and kun'yomi. We highly recommend you read the article and listen to the podcast episode (instead of just one or the other) for a deeper understanding of the concept. Trust us, your understanding of kanji readings will be so much better when you know about on'yomi and kun'yomi!

Now you can subscribe to the Tofugu podcast and come back later once you finish reading this article.

First, Some History

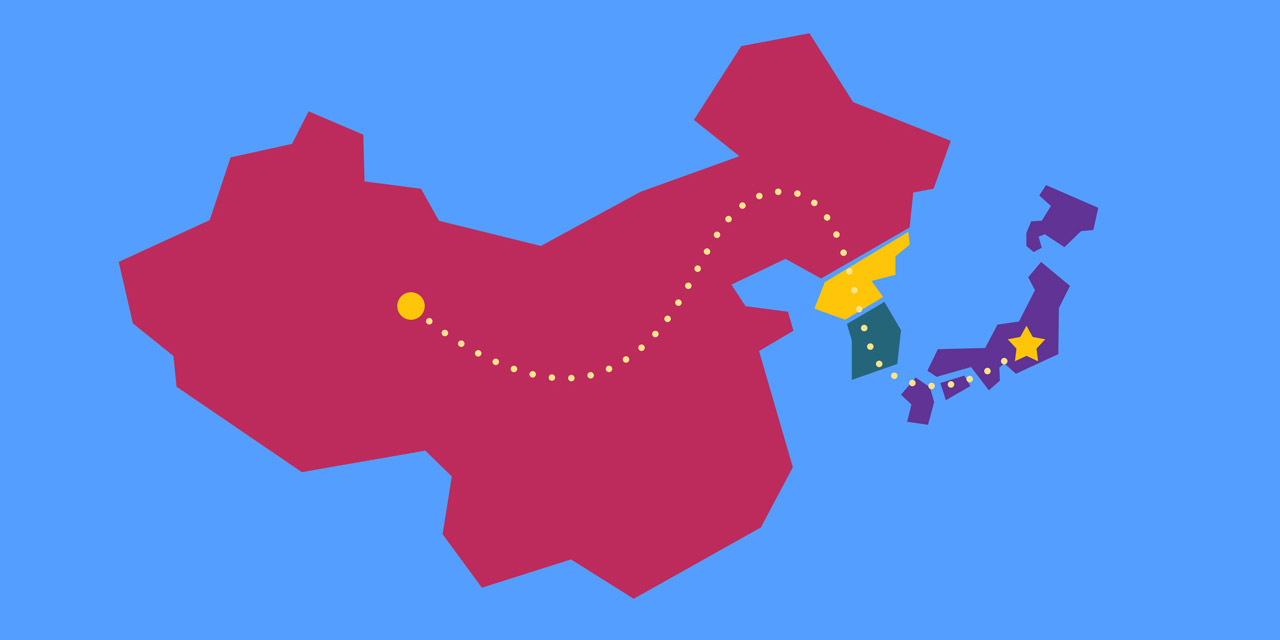

What we know today as "kanji" originated in China (they call it hànzì). These hànzì characters made their way through the Korean Peninsula, then hopped over to Japan mostly via Classical Chinese religious texts.

Japan was sooOOOooo in love with China at the time they adopted the Chinese writing system and applied it to their own language.

Taking the meanings of the Chinese hànzì and applying them to the Japanese language was fairly straightforward. If you saw the character 食, you'd know the meaning was "meal," "food," or something along those lines.

But the sounds of the Chinese language and the Japanese language are completely different. Despite this, Japan went ahead and adopted the Chinese readings for the kanji too.

What we know today as "kanji" originated in China (they call it hànzì). These hànzì characters made their way through the Korean Peninsula, then hopped over to Japan mostly via Classical Chinese religious texts.

"But wait," you say. "How is that even possible? Wouldn't that mean Japanese people started speaking Chinese?"

Short answer: no. Japan had their own language, and while it isn't the same as Japanese today, it wasn't Chinese either. They had their own words for things like water, fire, food, and all the other stuff that exists in life. Instead of converting the Japanese language into Chinese, they decided each kanji will have a Chinese way of reading it and a Japanese way of reading it.

These two readings are what we know as on'yomi and kun'yomi readings.

- On'yomi 音読み: Readings derived from the Chinese pronunciations.

- Kun'yomi 訓読み: The original, indigenous Japanese readings.

Notice how I said the on'yomi were derived from Chinese pronunciations? The Japanese didn't bring over the Chinese pronunciation for kanji wholesale.

Japanese is a very simple language (in terms of the number of sounds available to it). The Chinese language has far more sounds than the Japanese language does. Things like distinct pitches can lead to a complete change of meaning. Thus, Japan had to convert these Chinese readings into something that could be said within the Japanese alphabet of sounds. This, as well as Japan's lack of tones, is why they're (sometimes) similar, but not exactly the same as the originals.

Two Kanji Readings for the Price of One

Thanks to this adoption of characters and readings, almost all kanji have at least one on'yomi (Chinese origin) and one kun'yomi (Japanese origin) reading. So if you want to easily read Japanese you'll need to know them both. Here are some examples of kanji where both readings are commonly used:

| Kanji | Meaning | On'yomi | Kun'yomi |

|---|---|---|---|

| 水 | Water | すい | みず |

| 火 | Fire | か | ひ |

| 木 | Tree | もく | き |

| 国 | Country | こく | くに |

| 犬 | Dog | けん | いぬ |

| 山 | Mountain | さん | やま |

| 女 | Woman | じょ | おんな |

| 男 | Man | だん | おとこ |

| 内 | Inside | ない | うち |

| 目 | Eye | もく | め |

Note: Sometimes you'll see on'yomi readings written in katakana or English, and kun'yomi readings written in hiragana. This is a dictionary-only method used for differentiation. We won't be using them here.

Multiply this by pretty much every other kanji. Sure, some kanji will have one reading that is way more useful than the others, but for the most part, there will be an on'yomi and kun'yomi reading worth learning.

I'm going to leave it at that for now, so we can look beyond "one on'yomi and one kun'yomi," because, unfortunately, kanji readings are not that simple.

Single Reading Exceptions

Although most kanji have both an on'yomi and kun'yomi reading, there are exceptions. There are kanji that only have one or the other.

Kanji that only have an on'yomi reading are usually for things that either:

- Do not have a single, unified term (in Japanese), and thus took the Chinese reading for clarity, or…

- Were ideas or concepts that didn't yet exist for the Japanese people.

This may seem impossible. How could a language not have a concept for some things?

Remember these language transitions were happening way back in history and Japan was not yet the unified group of islands we know today. They were fractured, unrelated groups with unique leaders and systems of government that happened to live together on a couple of big islands. Not only did they enjoy fighting among themselves, they also did not have the Internet.

With that in mind, here are examples of kanji that only have on'yomi readings:

| Kanji | Meaning | On'yomi |

|---|---|---|

| 肉 | Meat | にく |

| 材 | Lumber | ざい |

| 感 | Feeling | かん |

| 点 | Point | てん |

| 医 | Doctor | い |

| 茶 | Tea | ちゃ |

| 胃 | Stomach | い |

| 職 | Work | しょく |

| 象 | Elephant | ぞう |

| 秒 | Second | びょう |

On the flip side, there are also kanji characters that only have kun'yomi readings because they are kanji created in Japan. This means they (Japanese elite/scholars/priests) took pieces of kanji characters and put them together to create a new kanji, for a concept that was native to Japan. These are called Kokuji 国字 (literally "national characters").

Here are examples of made-in-Japan kanji:

| Kanji | Meaning | Kun'yomi |

|---|---|---|

| 畑 | Field | はたけ |

| 姫 | Princess | ひめ |

| 匂い | Fragrant | におい |

| 峠 | Mountain Pass | とうげ |

| 枠 | Frame | わく |

| 籾 | Unhulled Rice | もみ |

| 鰯 | Sardine | いわし |

| 栃 | Horse Chestnut | とち |

| 込む | To Be Crowded | こむ |

| 咲く | To Bloom | さく |

So, you can't always assume a kanji will have two readings: an on'yomi and a kun'yomi. Sometimes it's just one of them, for the reasons listed above. That makes it simpler for you, the kanji learner!

Unfortunately, things are about to take a darker turn.

Why Are There So Many Kanji Readings?

Now that you know about Chinese and Japanese readings, everything should be cake right? Well, not exactly. Let's take a step back.

We know kanji came over from China via Korea, but history spans a long, long time. And if you know anything about Chinese history (or if you've played Dynasty Warriors), you know that the seat of power in China was pretty much constantly changing hands.

As an outsider, you probably think of these kingdoms as a bunch of "Chinese" people fighting each other while speaking the same "Chinese" language. China is big, there are many groups, many cultures, and – most importantly for this article – many languages.

As power in China changed, so did the "official" language.

As power in China changed, so did the "official" language.

These language shifts had a direct effect on the types of Chinese language that were brought to Japan. And not every kanji was brought over at the same time or from the same place.

For example, one version of Chinese pronounces the character 下 as げ while another pronounces it as か, centuries later. The character and the concept stayed the same, but for some reason Japan thought it would be neat to just adopt both Chinese readings for the same kanji. In the case of this kanji, we end up with words that use the げ reading:

| Kanji | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 下品 | げひん | Crude, Vulgar |

| 下巻 | げかん | Last volume (in a series) |

| 下旬 | げじゅん | End of the month |

| 下駄 | げた | Geta, Japanese wooden clogs |

| 下痢 | げり | Diarrhea |

And words that use the か reading:

| Kanji | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 地下 | ちか | Underground |

| 以下 | いか | Less than, Below |

| 地下鉄 | ちかてつ | Subway |

| 廊下 | ろうか | Corridor, Hallway |

| 却下 | きゃっか | Rejection |

Can you guess which reading arrived in Japan later? (Hint: it's the reading used with subway systems.)

Romance of the Three Language Shifts

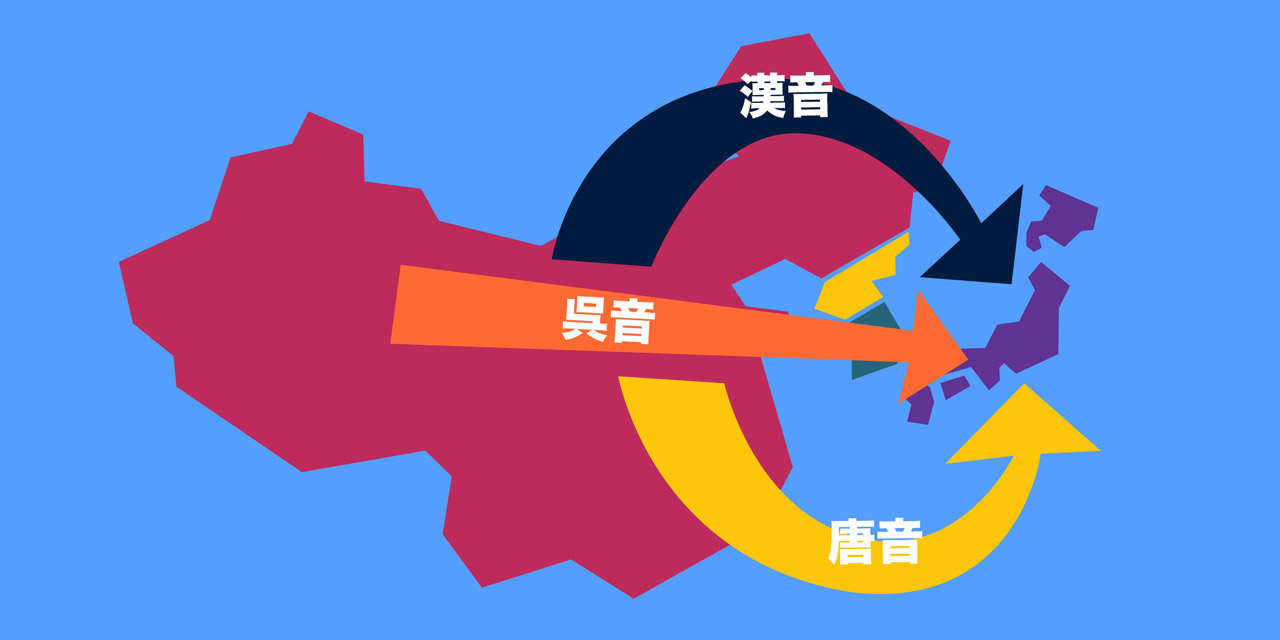

There were three major reading adoption periods in the history of the Japanese language:

- Go-on 呉音 (4–6th century): The Wu Dynasty pronunciation

- Kan-on 漢音 (7–9th century): The Han Dynasty pronunciation

- Tō-on 唐音 (1185–1573): The "Chinese" pronunciation

In pretty much every case, these characters and their readings were brought over by scholars of Buddhism and Confucianism in the form of religious and historical texts (usually through scrolls). Japanese scholars would then copy and adapt those texts into their own writing.

The majority of the on'yomi readings we use today are from the Kan-on group, though you'd never know it by looking at a dictionary. In fact, most dictionaries make no mention of the origins of the on'yomi readings and simply list them all without any differentiation.

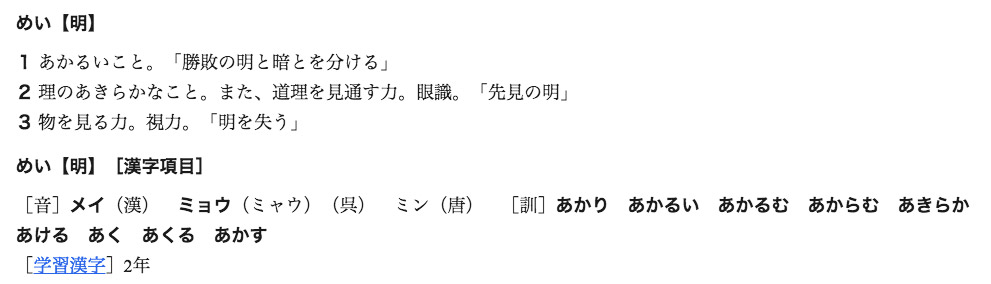

The two major Japanese-Japanese dictionaries (that I'm aware of) that do have this information are 新漢語林 and 新選漢和辞典. Some online Japanese dictionaries also list them for certain kanji, take this example of 明 in コトバンク:

Here you can see among the on'yomi readings that めい is from 漢 (Kan-on), みょう is from 呉 (Go-on), and みん is from 唐 (Tō-on). If you ever see these three kanji in a dictionary or resource, now you know what they're talking about!

Let's take a look at examples of kanji with multiple on'yomi readings, which, as you know now, are just readings from different Chinese language eras.

| Kanji | Go-on (呉) | Kan-on (漢) | Tō-on (唐) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 明 | みょう | めい | みん |

| 京 | きょう | けい | きん |

| 行 | ぎょう | こう | あん |

| 和 | わ | か | お |

| 頭 | ず | とう | じゅう |

| 珠 | しゅ | しゅ | じゅ |

| 子 | し | し | す |

| 清 | しょう | せい | しん |

If you know some Mandarin, you may notice the Tō-on readings are the closest to modern Chinese (specifically Mandarin Chinese). You can probably guess why: because they are the most recent additions to the Japanese language.

I can almost guarantee you'll never be asked about which on'yomi reading is from when or where, but knowing why there are multiple readings can help alleviate the overall confusion that comes with learning kanji.

Multiple Kun'yomi Readings

Just because kun'yomi readings originated in Japan, you may start out thinking there is only one kun'yomi per kanji, but it isn't that simple. There can be multiple kun'yomi readings for one kanji, just like there can be multiple on'yomi readings, but the reasons are slightly different.

In Japan, before there was writing, spoken language still existed and words for similar concepts would be said different ways.

In Japan, before there was writing, spoken language still existed and words for similar concepts would be said different ways.

For example, if you ask someone about a bubbly beverage in different areas of the United States you'll get multiple names for it: soda, pop, coke, or cola are all acceptable answers (though if we're being real, "soda" is the only correct one). Still, at the end of the day, everyone's describing the same tooth-rotting beverage.

When a kanji character that encompassed multiple concepts appeared, all the different ways of saying it went under a one character umbrella.

A modern example would look a lot like this: if the 🍪 emoji made its way to American shores, we might assign both "cookie" and "biscuit" to it as meanings, only use those words in speech, and replace all writing with the 🍪 emoji.

With that in mind, take a look at kanji that have multiple kun'yomi readings:

| Kanji | Vocab | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 上 | 上 | うえ | Up |

| 上げる/上がる | あげる/あがる | To Raise/To Rise | |

| 上る | のぼる | To Climb |

| Kanji | Vocab | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 下 | 下 | した | Down |

| 下げる/下がる | さげる/さがる | To Hang | |

| 下さい | ください | Please |

| Kanji | Vocab | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 生 | 生 | なま | Raw |

| 生む | うむ | To Give Birth | |

| 生きる | いきる | To Live | |

| 生える | はえる | To Grow |

As you can see, the words have similar meanings, but slightly different readings, living under the same kanji roof. You can imagine the person making these decisions thinking: "'To climb,' ‘to rise,' and ‘up' all have to do with upward things, so let's put them all inside 上. Woo wee, I'm such a genius!"

How Can I Know the Reading?

Now you know everything about the why and the where, but now it's time to cover the how.

How exactly do you know which reading is being used? The general rules are fairly simple, but with every language there are exceptions.

So, let's start by focusing on those patterns. This will help you identify the correct reading of a kanji, most of the time. The rest? We'll talk about that after you understand the basics.

On'yomi Compounds

A two-kanji (or more) compound usually takes the on'yomi readings. These are called jukugo 熟語. There are no hanging-on hiragana (okurigana) sticking out from the word.

Also, these words most resemble the Chinese language, which is just one character after another. When you see a compound word like this, chances are these kanji will use the on'yomi readings.

| Japanese | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 東京 | とうきょう | Tokyo |

| 先生 | せんせい | Teacher |

| 元気 | げんき | Energy |

| 最高 | さいこう | Best |

| 地下鉄 | ちかてつ | Subway |

Single Kanji Kun'yomi

Most words that consist of a single kanji, sitting all alone with no okurigana, are read with the kun'yomi reading. These include nouns and they make up the majority of beginner words you learn from textbooks and in classrooms.

| Japanese | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 人 | ひと | Person |

| 手 | て | Hand |

| 心 | こころ | Heart |

| 南 | みなみ | South |

| 冬 | ふゆ | Winter |

Single Kanji On'yomi

While less common than single kanji words that use the kun'yomi reading, there are many instances of single kanji using the on'yomi reading. This is especially true for single kanji numbers, but there are plenty of other examples as well.

| Japanese | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 本 | ほん | Book |

| 天 | てん | Heaven |

| 字 | じ | Character |

| 文 | ぶん | Sentence |

| 一 | いち | One |

Kun'yomi with Okurigana

If a kanji has hiragana attached to it, it almost always uses the kun'yomi reading. These kana suffixes are called okurigana 送り仮名 and they are mostly adjectives and verbs, but they can be used for nouns too.

| Japanese | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 大きい | おおきい | Big |

| 食べる | たべる | To Eat |

| 行く | いく | To Go |

| 玉ねぎ | たまねぎ | Onion |

| 乗り場 | のりば | Bus Stop |

Kun'yomi Compounds

Some kanji compounds words, especially those that have to do with nature (very Japanese) or cardinal directions, can take the kun'yomi readings for both kanji. While not as common as on'yomi compounds, they do exist in some very common words.

| Japanese | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 月見 | つきみ | Moon Viewing |

| 南口 | みなみぐち | South Exit |

| 朝日 | あさひ | Morning Sun |

| 虫歯 | むしば | Cavity |

| 場合 | ばあい | Case |

Exceptions

There are, of course, many exceptions to the rules above:

- Words that contain kanji that have both on'yomi and kun'yomi readings.

- Kanji that get assigned to katakana words.

- Words with kanji that have readings that don't make any logical sense when you look them up in the dictionary.

You can read about all of these and more in our article about weird kanji.

How To Learn Kanji Readings

Now that you know the basics patterns, it's time to take a look at ways you can learn kanji readings. It's not easy, especially when one kanji can have so many (correct) ways of reading it.

First, let's consider the traditional method for learning kanji readings.

- Teacher tells you to learn the kanji readings, because they're going to be on the quiz.

- You take the quiz.

There is no thought about what kanji reading(s) are more useful to know. As you saw from the examples above, not all kanji readings are created equally. Some readings get used a lot. Others almost never. And you're just being asked to memorize sounds without much context.

We're not going to get into a huge amount of detail about how to choose good kanji readings to learn here. We already did that in our article about how to learn kanji. So, let's paint in broad strokes (and I'll point you in the right direction when things need to get more specific).

1. Just Learn One Reading Per Kanji

This goes against what a lot of people say and do, so stick with me here. Learning all of the readings of a kanji actually means you are learning less.

You have multiple strands of weak, new information in your head. By trying to hold onto all of them, you end up holding onto none of them (you can't remember the readings).

However, by learning and associating one reading for the meaning (which you should already know), you're creating a stronger bond. Thus, you will learn this one reading easily.

Also, you need to have faith in one thing: the long run, you will learn all the important readings for this kanji, but for now, you are learning one. We'll tell you why in the next section.

2. Choose the "Best" Kanji Reading to Learn

You are only learning one kanji reading. So which one should you learn? The "best" one, of course, but how do you know which reading that is?

For most kanji, there will be a single reading that shows up in 80–90% of the vocabulary. Let's consider – as an example – a kanji that has three readings. We will also assume – for the sake of this example – that each reading will cost you ten minutes of time. Here is the value of each of that kanji's readings:

- Kanji Reading 1: Used in 90% of the vocabulary.

- Kanji Reading 2: Used in 7% of the vocabulary.

- Kanji Reading 3: Used in 3% of the vocabulary.

You are paying ten minutes of time to learn each reading. One of the readings is clearly way more valuable than the others. Why would you pay the same amount of time for something that has, comparatively, almost no value? You could use the extra time to learn more kanji (which means you will be able to read more overall).

Of course, the percentages will be different from kanji to kanji, but in general there will be one reading that is way more valuable than the others. You need to pick that reading out. Forget about on'yomi, forget about kun'yomi, and just think of the "best" reading as "the reading."

So what about the other readings? Aren't they important to know?

3. Learn Other Readings Through vocabulary

You will learn the other kanji readings by studying vocabulary. So really, you're not missing out on anything by not learning the less common readings along with the kanji.

You won't have the issue of crossing your memory wires (readings learned through vocabulary will be more associated with that vocabulary word than the original kanji), and assuming you are learning useful vocabulary words, you will naturally learn the next most common kanji readings.

You will learn the other kanji readings by studying vocabulary. So really, you're not missing out on anything by not learning the less common readings along with the kanji.

Using this method, you will learn the kanji readings and words that are most common. You will also be able to learn more kanji in less time.

That means you will be able to read a higher percentage of Japanese text sooner, and the faster you do this, the more you'll be able to learn (because there's nothing better for learning Japanese than reading Japanese).

This method requires a lot of long term thinking, but you will get to the end much, much faster.

Next Steps to Learning Kanji

Now you know where kanji came from (China), what their readings are (on'yomi and kun'yomi), and a bit about how and when to use them. But it's not over yet.

Since language is fluid and old and complicated, there are still exceptions to rules everywhere. The best thing to do is use these rules as a first guess, then look up the answer to see if the word you're looking at follows the rules or not.

Or, if you want to be a kanji master, you can start to learn both the on'yomi and kun'yomi readings for kanji with the vocabulary words that use them. However, don't just jump in right away and try to memorize them all at once, as there are over 2,000 kanji used in everyday life in Japan. That's a lot of information, and quite a pit of chaos, especially to the new learner.

To bring some order to this chaos, we recommend looking at our article on spaced repetition learning, as well as our big how to learn kanji guide. You will learn how to choose the right information to learn, then build yourself a durable system for getting it into your long term memory.

And if you don't feel like spending time putting together your own study technique, take a look at WaniKani for a kanji method that does all this and much more. The first three levels are free and cover 75+ kanji (meanings plus the best readings) and 200+ vocabulary words that use the kanji (so you can learn more than one kanji reading). This is more than most Japanese classes can finish in a year, and you'll finish it all in a month. If you go through the whole system, you'll be able to learn over 2,000 kanji and 6,000 words.

Whatever you end up doing, I hope this article helped you understand kanji readings. It's not easy, but once you know what each reading does, and where it comes from, it gets simpler. Don't be overwhelmed by all the readings either. The more readings that you learn, the easier it gets (that's good news).

Have faith it'll get better and keep moving forward. Good luck, linguistic adventurer!