The Japanese learning industry has, for all intents and purposes, failed you. It's not your fault that learning kanji is like hitting your face on a curb, it's the industry as a whole. Sure, there are pockets here and there that are pretty smart about it, but they tend to be small and nobody really knows about them. Most likely, you know what your teachers says about kanji, or what Rosetta Stone Japanese (doesn't) say about kanji, or what your textbook throws at you… But, here's the problem, though: You're learning kanji from native Japanese speakers, and they have no idea what it's like to learn kanji anymore (and even if they do, they just emulate the way Japanese school children learn kanji), which really just doesn't work.

The Japanese learning industry, on a whole, has failed us when it comes to kanji learning. But, you can learn from their mistakes, and in doing so, learn how to fix the way you learn kanji.

FAILURE #1: You Learn Kanji Stroke By Stroke By Stroke…

Sure, there's something to be said about learning correct stroke order. I'm all for that, but the problem is that it ends up putting emphasis on learning kanji stroke by stroke by stroke. When kanji is simple, it's easy to learn this way. Three strokes? Only three things to learn. Huzzah! But, when you start out learning kanji like this (i.e. when you think of kanji as a bunch of separate strokes), you keep learning kanji like this. That's why in most Japanese classes, when the kanji homework goes out, people automatically see how many strokes a kanji has. "I know a 20-stroke kanji, I'm impressive!" people think. No. You're not. Thinking this way is unimpressive. Thinking of kanji as a bunch of strokes is inefficient. A 20-stroke kanji = 20+ different things you have to remember. If you think of a kanji as individual strokes making up the whole, then you've already failed. So how should you think of kanji, then?

FAILURE #2: You Don't Learn Your Kanji Radicals

Oh sure, you might learn a few radicals here and there, like the water radical (just a few little strokes next to a kanji). "If you see this," the kanji resource says, "you'll know that this kanji probably has something to do with water." For the most part, though, radicals are a distant afterthought in the kanji-learning world, and this is a huge mistake. Most people teach radicals (if they teach them at all) as a method for looking up kanji in a paper dictionary. When's the last time you used one of those? It's probably been a while. Thank you smartphones.

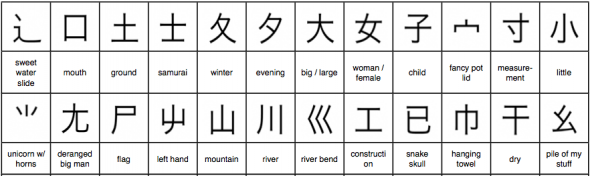

Instead, learning radicals should be treated like building blocks. Remember how I said kanji should not be learned stroke-by-stroke? More complicated kanji should be put together radical-by-radical. If you take the time to learn the 200-250 kanji radicals (it may seem like a lot, but it's really a pretty quick process), you can put a fairly complicated kanji together in 3, maybe 4 steps. Think of radicals like the ABCs of English. You can't put together the English word FAILURE if you don't know the letters F-A-I-L-U-R-E, right? If you didn't know those letters, and just wrote the words FAILURE by trying to mimic those weird letter shapes — and did that 2000 times — you would be in trouble. Learning radicals is like learning the letters of the alphabet (admittedly at a much bigger scale). Still, you cut down on the memorization required for every single kanji by 300-800%. Here's an example:

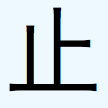

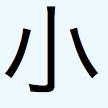

Now, this kanji isn't particularly difficult, but you get the drift. Learning this kanji stroke-by-stroke would set you back eight steps (because there are eight strokes). Instead, let's take a look at the radicals that make this kanji up. If you learn all the kanji radicals (or, at least the ones I recommend), putting this particular kanji together can be done in a mere 3 steps, depending on which radicals you use. That's a 260% less to learn which means you're saving valuable time and brain-space.

As you can see, these three "radicals" can be put together (like letters in a word) to create the kanji above. The first one (止) makes up the top portion, the second one (小) takes up the bottom, and the third (ノ) rounds it out. The best part is that you associate these radicals with names and concepts, which means you can come up with some kind of mnemonic story to help you remember what goes where (more on mnemonics below).

In summary, everyone should learn their radicals before even thinking about learning kanji. If you don't, it's like building a highrise with no foundation, or like learning to read English without memorizing the ABCs.

Failure #3: You Memorize Instead of Acquire

Good things can be said about repetition and "memorization." I think they're a necessary part of kanji learning, but everything has it's limits (and you can use all the help you can get when it comes to kanji). One of the problems I have with the "normal" way people have you learn kanji is that they give you 10-20 kanji, sit you down with a kanji worksheet, and have you write the kanji over and over again (and of course, the focus is on the number of strokes, right?).

The problem, though, is with our brains. First of all, there's only so much information (or so many steps) we can fit in our short term memory. That means as soon as you move on to the next kanji, there's a good chance you're already forgetting the one before it. Another problem is that with too much repetition, our brains switch to autopilot. At that point you aren't learning any more, you're just going through the motions. To solve this, there are a couple of solutions.

SOLUTION A) First of all, don't think of the kanji as strokes, think of them as particles. This will help you learn more effectively (and get the information in your long term memory more quickly). When you're practicing, think of the individual radicals that you're writing, and how they go together to form the whole kanji. The more you do this, the faster you'll be able to learn kanji.

SOLUTION B) Don't write a single kanji more than three times in a row. If you have multiple kanji to practice, switch back and forth and go back to previous ones. Come up with some kind of pattern. I would recommend something like this. Each letter represents a kanji, and each time it shows up it should be written for practice: A, A, A, B, B, B, A, B, C, C, C, A, B, C, D, D, D, A, B, C, D, E, E, E… etc. When you run out of space for "A" kanji, you would just start at "B" the next time around. This way you are forcing your brain to actually think and process the information, instead of hitting autopilot the moment you've written a kanji for the 4th or 5th time.

SOLUTION C) Apply some kind of mnemonic strategy to your kanji. Mnemonics help you to remember things. They basically leave hints in your brain that when seen trigger another memory, which really helps you to remember kanji more effectively. One way to do this is to come up with "stories" for your kanji. If you've learned the kanji radicals, it is pretty easy to do. If you take the example above (ho 歩), we can use the three radicals to come up with a story to help us remember whatever it is we want to remember. The radical examples below are ones I've given meaning to. You can come up with your own meanings if you want to, or use a set that someone else has developed.

止 is a radical that means STOP 小 is a radical that means SMALL ノ is a radical that means SLIDE So, we can use these three concepts / words and put them together in a way that helps us remember that the kanji 歩 means "walk." Here's one: "Stop! It's a small slide. We will walk from here" (you know, because zombies hang around slides). As long as you know the radicals already, the hints to trigger this little "story" will be right in the kanji, every time you see it.

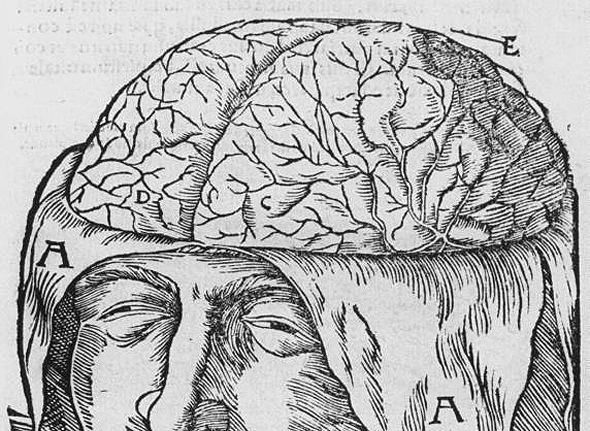

Of course, we could get even more in depth with it and start associating emotion as well as our senses. This gets into the concept of creating "flashbulb memories" for yourself (these are memories your brain produces during traumatic or incredible events, that's why you remember where you were, say, when you learned about 9/11). By imagining the emotion you felt when you saw the small slide, or the smell of the aluminum, or perhaps even the shock you felt when you saw how small it was, you can make this memory a lot stronger by tricking your brain into thinking it was really important. The more senses or emotions you associate with it (you really have to imagine they're happening, though!), the more likely you are to remember. This may seem like a lot of work at first, but it actually gets quite quick and easy as you practice.

You can even take this a step further and learn the pronunciation of the kanji like this as well. Once you know the meaning of the kanji, you can learn the pronunciation using a similar strategy. For the kanji 歩, the most common on-yomi for this kanji is ほ (ho). When you know this, you can come up with another story that uses "ho" in it. Maybe something like: "When you walk around, be careful about stepping on a hoe (ほ). Since we know the meaning of the kanji from the previous story, we can use that as our hint to figure out what the pronunciation of it is as well. Beyond that, though, I'd recommend also learning the common words that use that kanji, since there are often plenty of different ways to pronounce the same kanji, and learning through example is the best way, I think.

FAILURE #4: You Learn Kanji Like Japanese School Children (i.e. In The Wrong Order)

When Japanese school children learn kanji, they go from simpler kanji meanings to more complicated kanji meanings. Sometimes, a simple kanji will have a simple meaning, but sometimes it won't. Take a look at these kanji, for example. These are learned in secondary school (i.e. they are "higher level" kanji), but if you look at them, you'll notice they're really, really simple to write. Two or three strokes each.

乙 了 丈 勺

Even though these kanji are simple to write, the meanings aren't as simple, which is why Japanese school children don't learn them until later in their education. On the other hand, take a look at these kanji, which have very simple meanings associated with them, yet consist of many, many more strokes. These are learned by second graders in elementary school. We're talking tiny little kids, with tiny little brains.

曜 線 鳴 算

The problem with a lot of Japanese learning resources is that they emulate this Japanese school children method of learning kanji. The thing they seem to have totally forgotten is that you, as someone who is learning Japanese as a second (or third, or fourth) language, probably are not a child (not to mention a Japanese child, in Japan), which means it really doesn't matter if you learn kanji with difficult meanings earlier. You already understand the meanings behind the words, because you've learned them all in English. The difficult part is the actual kanji itself (and how to write / read them), not the meaning associated with that kanji. Because many resources forget this, you are introduced to more difficult kanji early on just because the meaning of the kanji is easier.

Instead, everyone should learn kanji based on the simplicity of the kanji itself. Who cares about the meaning. Start with 1-stroke kanji and work your way up. There are approximately 2,000 kanji you have to learn no matter what, so you might as well put them in an order that makes a lot more sense. By starting simply and moving your way up, you are able to build one kanji upon another. You'll find that more complicated kanji are really just made up of less complicated kanji (or radicals). But, if you learn kanji the way Japanese school children learn them, it feels random, overwhelming, and just plain confusing. Learning kanji isn't the same as learning vocabulary in Spanish, German, or whatever. It's its own monster, and should be treated that way.

FAILURE #5: You Don't Use The Best Tools Out There

I'm pretty sure most teachers today don't say "okay, when you go home, I want you to fire up your Spaced Repetition System application to practice yoru kanji!" No, it's more like "okay, when you get home write this kanji a gazillion times in this kanji sheet until you feel tired and lethargic." Now, you don't need fancy tools to do anything. Tiger Woods could pick up a garbage golf club and still beat you every time. But, when it comes to language learning, it certainly doesn't hurt.

First of all, get on the SRS train. Spaced Repetition Systems space out reviews because the best memories are formed when there is time between recall. If you are doing better, they will make the space bigger. If you're doing worse on a word or kanji, the space will get smaller. They're essentially smart flashcards. Anki, iKnow.jp, and Memrise are all popular SRS applications amongst Japanese learners. If you want to stick with physical paper and pen, Rainbowhill has a pretty good method.

Then comes the question of mnemonics. Hesig's Remembering The Kanji is good for learning the meanings of the main kanji, but that's it. This is a book that you'll want to pair with one of the SRS methods above. Also, there is WaniKani, which combines everything: SRS, mnemonics, and ordering. It does require a subscription, but the first two levels are free so you can see if it's effective for you.