Table of Contents

The Basics

We all know what a sentence is, but have you ever heard of a clause? We're talking about grammar here, not Santa Claus or your cat's claws. Being able to recognize clauses in Japanese sentences will make it much easier to parse complicated sentences, and help you to develop a deeper understanding of Japanese grammar.

Simple Sentences

We'll start things out by looking at simple sentences. A simple sentence is a sentence with only one clause. In this case, the clause and the sentence are the same thing! Yay for simplicity!

Before we jump into the grammatical nuts and bolts of clauses, let's look at it from a somewhat simplified point of view. In general, we could say that the purpose of a sentence is to state a "thing" that we want to talk about, and then to give some information about that "thing."

| Thing | Info About Thing |

| The bus | is coming |

| The sky | is bright |

| This | is my house |

In English, both the "thing" and the information about that thing are required for a clause to be complete. In a sentence like "It's hot outside today," "it" doesn't really refer to anything, but it has to be there to make the sentence grammatically correct. To put it another way, English requires that every clause have a subject. That is, the subject is an essential clause element in English. Of course, the second part of the sentence, or the "info about the subject" is also required in English.

Essential Clause Elements

Now let's turn the focus back to Japanese. As you may know, the subject is often dropped in Japanese. This means that, when the thing we want to talk about is known from context, we don't have to mention it at all.

| (Thing) | Info About Thing |

| (バスが) | 来る |

| (空が) | 明るい |

| (これが) | 私の家です |

In the examples above, the thing being discussed is placed in (parentheses) to show that it is optional. You can include the "thing" you're talking about if it's not clear from the context of the conversation, but it's not required in the same way that English requires a subject. The only essential clause element in Japanese is that second part of the clause — the info about the thing you're talking about.

Predicate

This "info about the thing you're talking about" is called the predicate. A range of different word types can serve as the predicate of a Japanese sentence:

| Noun: | (それは)犬。 | That is a dog. |

| な-adjective: | (花子は)きれい。 | Hanako is pretty. |

| い-adjective: | (今日は)暑い。 | Today is hot. |

| Verb: | (今から)歌う。 | Now I will sing. |

You can dress up these predicates with other clause elements to add more meaning and complexity, but all that you need in order to form a complete simple sentence in Japanese is a predicate!

Nonessential Clause Elements

So what are these nonessential clause elements that we can use to dress up the predicate? There are quite a few, and each of them are complex enough to deserve their own page, but we'll give a simple introduction to each of them here.

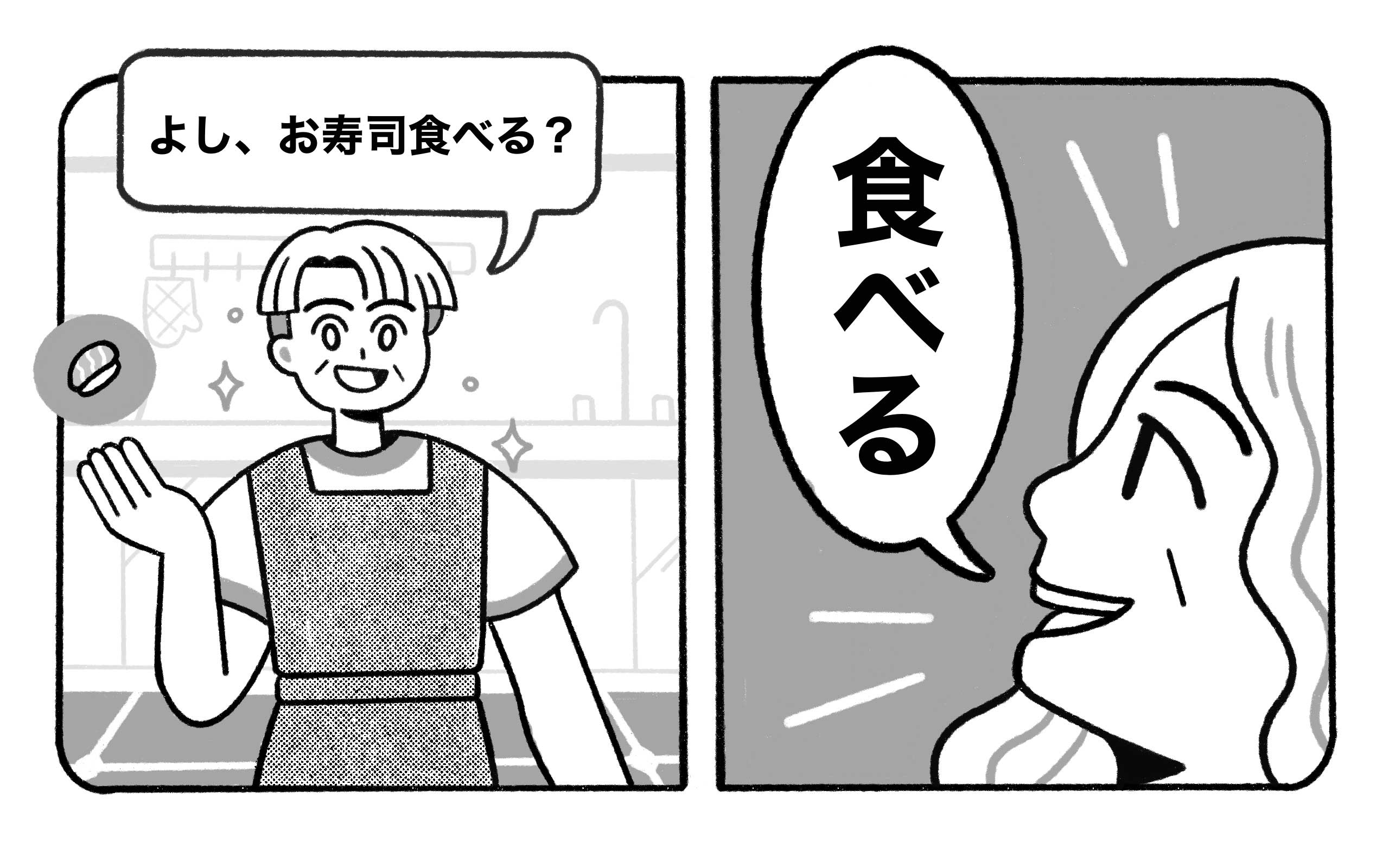

Let's start with a simple predicate — the verb 食べる (eat). This verb could be used all on its own to create a complete sentence in Japanese. For example, your dad (who is known for his sushi making skills) is gearing up to make some sushi for your mom. He asks her, よし、お寿司食べる? (Alright, want to eat some sushi?). She emphatically responds:

- 食べる!

- I do!

As you can see, there is a pretty big difference between the Japanese example sentence and the English translation. The English sentence contains a "thing" (I) and "information about the thing" (do). In Japanese though, the sentence is boiled all the way down to just that "information about the thing," or in other words, a predicate verb: 食べる.

While this basic, predicate-only sentence is possible, it's a bit limited when you want to add new information to a context. Let's check out each of the categories of nonessential clause elements that we can add on to a predicate.

Object

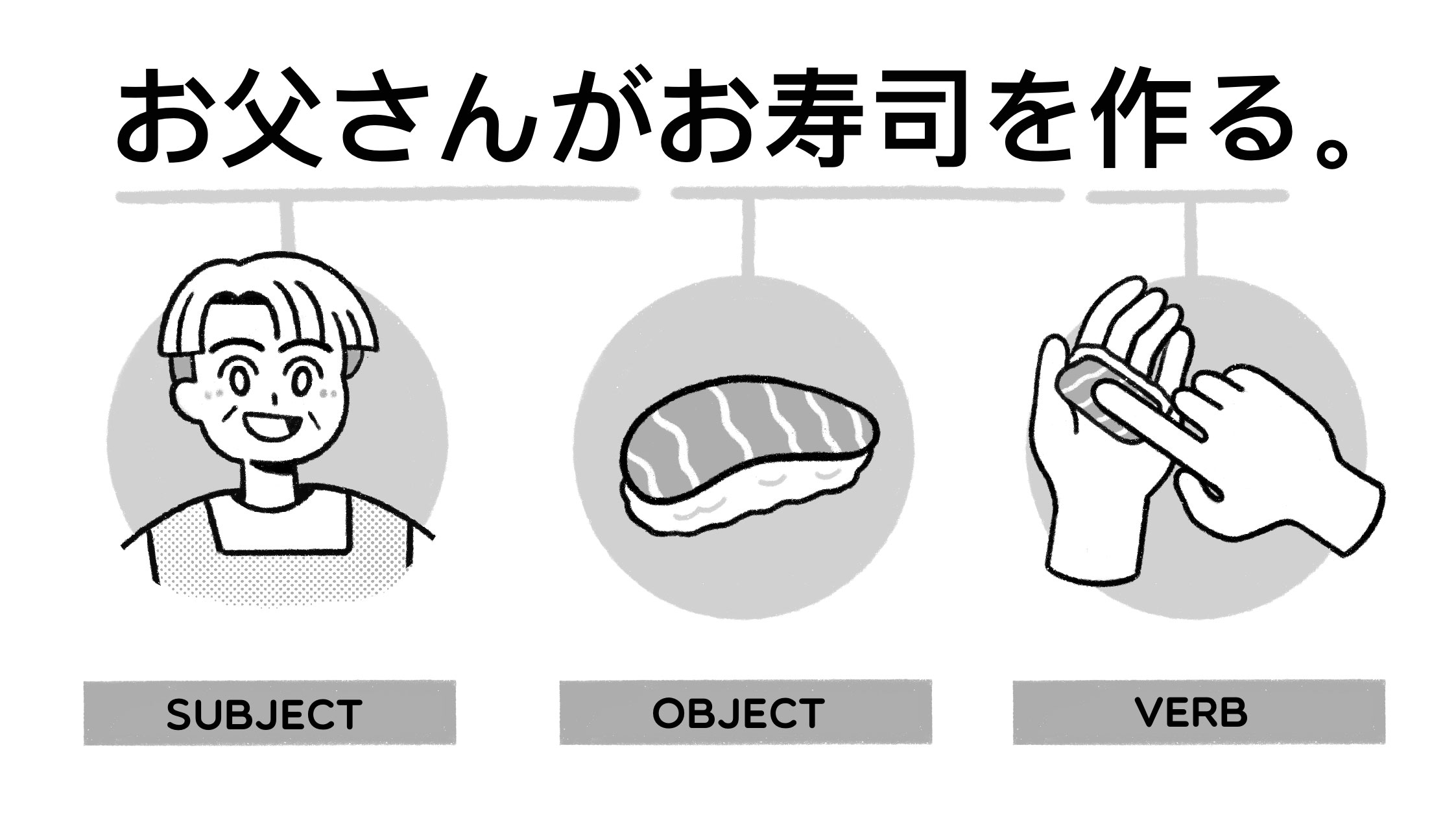

We'll start off by adding an object to the verb 作る (make). An object is the element of a clause that is acted upon by a transitive verb. In Japanese, this element is marked by the particle を:

- お寿司を作る。

- Make sushi.

In this sentence, お寿司 is marked as the object by the particle を. This tells us what is being 作るed.

Subject

Next, let's add a subject in. Subjects are typically marked by the particle が in Japanese:

- お父さんがお寿司を作る。

- My father makes sushi.

In this sentence, the particle が marks お父さん as the person who makes the sushi, showing that it's him and not anyone else who is going to do it. How important this emphasis is varies a lot depending on the context, though.

Topic

On the surface, the topic seems quite similar to the subject, but there are some differences. Topics are generally marked by the particle は:

- 毎週日曜日はお父さんがお寿司を作る。

- Every Sunday, my father makes sushi.

In the example sentence above, the particle は marks 毎週日曜日 as the topic of this sentence, and also the topic of the conversation, until it shifts to something else. This is a little different from a subject, which can change from clause to clause without the topic necessarily shifting. For example, if we follow up our example sentence with それから、お母さんがその寿司を一人で食べる (then, my mother eats the sushi all by herself), we can see that the subject of the new sentence is お母さん (marked by が). The topic, however, is still 毎週日曜日.

Adverbials

Another of the optional clause elements is adverbials. Adverbials give information about the circumstances surrounding a sentence, such as when, where, why, or how. They come in many shapes and forms, but you'll often see them marked with particle に and particle で:

- 毎週日曜日はお父さんが台所でお寿司を作る。

- Every Sunday, my father makes sushi in the kitchen.

Now we've added 台所で (in the kitchen) to our sentence. This tells us where the sushi making takes place.

Sentence Final Particles

Lastly, let's add a sentence-final particle to the end of our sentence:

- 毎週日曜日はお父さんが台所でお寿司を作るの。

- Every Sunday, my father makes sushi in the kitchen.

Sentence-final particles are often very hard to translate into English. In this example, we see that the particle の has been added to the end of the sentence. This adds an explanatory nuance.

Other common sentence-final particles include the conversational particle よ and particle ね.

Sentence Order

Japanese is said to be an "SOV language," meaning that the typical order of clause elements in a sentence is "subject, object, verb." English, on the other hand, is an "SVO language," meaning that sentences tend to take a "subject, verb, object" order. Let's turn back to our previous example to see how this works:

- [お父さんが] [お寿司を] [作る]

sub obj verb - [My father] [makes] [sushi]

sub verb obj

In English, it's very unnatural to deviate from this sentence order, unless you intend to sound like Yoda <(-.-)> In Japanese, however, it's much easier to switch up the order of your sentence. Thanks to those handy-dandy particles, it's clear what clause element a word is supposed to be even if the order is unusual. For example, let's say that you call up your mom on Sunday to see what she's up to. She says:

- 寿司を作っているの、お父さんがね。私は見ているだけ、お父さんのことを!

- We're making sushi, well, your dad is. I'm just watching, your dad that is.

In the example sentences above, you can see that the sentence is in a pretty wacky order! The first sentence is OVS (object: 寿司を), (verb: 作っている), (subject: お父さんが). By placing the subject at the end of the sentence, it starts off sounding like she is making the sushi, until she throws in at the end of the sentence that it's your dad doing it, almost as though it's an unimportant detail. Oh Mom… 😑😅 In this way, Japanese sentence order can be manipulated to highlight information at the beginning of the sentence, or tuck it away at the end like an afterthought.

Beyond the Basics

In the previous section, we looked at the elements of a simple sentence, which is a sentence that contains only one clause. In the following sections, we'll take a look at sentences that contain multiple clauses.

Complex Sentences

A sentence that contains multiple clauses is known as a complex sentence. Generally speaking, there are two main ways to form a complex sentence — you can link clauses together, and you can embed clauses inside each other.

Linked Clauses

Clauses are considered "linked" when the end of a clause attaches to the beginning of another, rather than having a period in between. Let's see what this looks like:

- 今日は忙しい。ストレスが溜まっている。

- Today I'm busy. I'm feeling stressed out.

As it is right now, we have two simple sentences, one after the other. We can use our judgement to determine that the first sentence is the reason for the second sentence, so wouldn't it be nice if these were combined into a complex sentence, rather than just listed one after another? This would result in a more interesting and advanced sentence structure. Let's look at two ways of combining these sentences — with conjunctive particles and with conjugation.

Conjunctive Particles

- 今日は忙しいから、ストレスが溜まっている。

- Today I'm busy, so I'm feeling stressed out.

As you can see, we've added the particle から to the end of the first clause, allowing it to attach directly to the beginning of the next clause. から makes it clear that the first clause is the reason for the second clause, so it's similar to the English conjunction "because." There are a range of other particles that function similarly, but add a different shade of meaning, such as ので, けど, なら, etc.

Conjugation

In addition to particles, there are some conjugation forms that allow one clause to link up with another. A conjugation is when a word changes its own structure, which is a capability of verbs and い-adjectives in Japanese. Let's see how it works:

- 今日は忙しくて、ストレスが溜まっている。

- Today I'm busy, so I'm feeling stressed out.

By conjugating the い-adjective 忙しい into the て form, it can now attach to the beginning of another sentence. This option is a little less direct than adding a conjunctive particle, since the particle makes the relationship between the two linked clauses explicitly clear.

Embedded Clauses

You can also form a complex sentence by embedding a clause inside another clause. There are a few different ways to do this, such as through quotation and noun modification. We'll take a look at both in the following sections.

Quotation

One way to embed a clause inside another is to treat the embedded clause as a quotation. This is not all that different from English, as you'll see:

- 弟は「火星に住みたい」と言いました。

- My little brother said, "I want to live on Mars."

First, let's locate the two clauses in this sentence. We have the embedded clause, which is 火星に住みたい, and we have the main clause, which is 弟は〜と言いました. In this case, the embedded clause is surrounded by 「quotation marks」 (or 鉤括弧 in Japanese). Unlike in English though, these quotation marks are not required for signaling a direct quote, so you can't always rely on them being there. In fact, there is no marked difference in Japanese between direct and indirect quotes — you'll even see quotation marks added to indirect quotations, just to add emphasis.

Next let's take a look an an indirect quotation that doesn't use any markings. A good example of this is when you express your thoughts using 〜と思う:

- 人間は火星に住めないと思う。

- I don't think that humans can live on Mars.

The embedded clause is a little harder to see in this case, since it isn't surrounded by quotation marks. If you're uncertain, look for the particle と, which acts almost like a spoken quotation mark. The most probable interpretation of this sentence is that 人間は火星に住めない is the embedded clause, and 〜と思う is the main clause. We can assume that 私は has been omitted from the beginning of the sentence since it's clear that I am sharing my thoughts, so there's no need to point myself out. You could also argue that 人間は〜と思う is the main clause, and 火星に住めない is the embedded clause, meaning "Humans think that you can't live on Mars." This is one of those cases where you need to use context clues to figure out the intended meaning.

Noun Modification

The other way that a clause can be embedded inside another is when the embedded clause modifies a noun. In other words, a clause can modify a noun, like an adjective does. Let's check it out:

- 可愛い猫

- cute cat

In the example above, we see that the noun 猫 (cat) is being modified by an adjective, 可愛い (cute). This allows us to describe the cat in more detail. We can also modify a noun with an entire clause:

- スーパーの前で拾った猫

- the cat that I found in front of the supermarket

In this example, the clause スーパーの前で拾った modifies 猫. In English grammar, this is called a "relative clause," and it comes after the noun. That's why you see "the cat that I found in front of the supermarket" in the translation. In Japanese, noun modifiers always come right before the noun.

A noun with a clause modifier can be used in any part of a sentence. Let's check out an example with スーパーの前で拾った猫 being used in a sentence. Can you tell which clause element it is?

- 残念ながら、[スーパーの前で拾った] 猫が逃げたんだ。

- Unfortunately, the cat that I found in front of the supermarket ran away.

If it's hard to tell, we recommend removing the embedded clauses to find the simpler, main clause. This means removing the part of the sentence you see above in [brackets]. If you do that, you're left with 残念ながら、猫が逃げたんだ (Unfortunately, the cat ran away). 猫 is the subject of this sentence, right? You'll even notice the particle が after it, marking it as such. Adding the relative clause back in doesn't change that, it just tells us a bit more about that subject 猫.

Let's step this up a notch. You can have a sentence with multiple relative clauses in the same sentence, which can be pretty tricky to parse:

- [スーパーの前で拾った] 猫が [お母さんからもらった] ランプを壊した。

- The cat that I found in front of the supermarket broke the lamp that I got from my mother.

Yikes! What a sentence! We already know that スーパーの前で拾った is modifying 猫, but what else is going on? Let's remove the relative clauses real quick to see the bigger picture. If we do that, we get 猫がランプを壊した (the cat broke the lamp). So where does お母さんからもらった fit in? You guessed it! It's a clause that modifies ランプ, telling us that it's a lamp that I got from my mother.

です and ます in Clauses

In Japanese, you can use です and ます to express politeness towards the person you're talking to. These politeness markers can be used in a clause, but not always.

です and ます in Linked Clauses

です and ます can appear in linked clauses, which are basically two independent sentences combined into one. Here's an example:

- 桜が満開ですから、お花見に行きます。

- The cherry blossoms are in full bloom, so we will go to see them.

See how there are two clauses, [A: 桜が満開です] and [B: お花見に行きます]?

- [A: 桜が満開です]から、[B: お花見に行きます]。

- [A: The cherry blossoms are in full bloom], so [B: we will go to see them].

They're connected by the particle から. Without から, clause A and clause B are two independent sentences. This means it's possible for both clauses to have です and/or ます in them.

However, note that a single politeness marker located at the end of the full sentence would usually work just fine, too. For instance, in the previous example you can replace the first politeness marker です with だ to turn it to the plain form while keeping ます at the end of the sentence, like this:

- [A: 桜が満開だ]から、[B: お花見に行きます]。

- [A: The cherry blossoms are in full bloom], so [B: we will go to see them].

The overall tone of this sentence remains polite as long as it ends with a politeness marker. In Japanese, the end of a sentence is what sets the tone, so make sure to have a politeness marker at the end of the sentence if you want to sound polite. On the flip side, having a politeness marker in the middle of the sentence without having one at the end of the sentence would be a bit unnatural.

One exception to this would be when quoting something someone said. Let's check out how that works in the next section.

です and ます For Quoting Someone

です and ます can be used in the middle of a sentence to quote something someone said, such as:

- 近所の人から「桜が満開ですよ」と教えてもらいました。

- A neighbor told me, "the cherry blossoms are in full bloom."

In this example,「桜が満開ですよ」is a direct quote, meaning the exact words your neighbor said to you, or at least what you remember them saying. The quote in this example sentence is considered an embedded clause because it's inserted inside the main clause: 近所の人から…と教えてもらいました.

However, note that です and ます can't be used in an embedded clause for indirect quotes. Indirect quotes are a summary of what someone said, not their exact words. Here's an example of an indirect quote:

- 近所の人から桜が満開だと教えてもらった。

- A neighbor told me that the cherry blossoms were in full bloom.

In this sentence, 桜が満開だ is a summary of the neighbor's message. Notice that this example doesn't have 「」(kagikakko), which are generally used for direct quotes. But you don't exactly see quotation marks (or a lack of them) when you're having a real-life conversation. So what other hints can you use to tell what's being said is just a summary and not a direct quote?

Compared to the politeness markers です and ます, だ is sort of an "assertiveness" marker. Using it without a communicative particle like よ or ね would sound standoff-ish and abrupt in spoken Japanese. So a sentence ending with だ wouldn't sound like something that's used in an actual conversation.

Since this clause is no longer a direct quote, a politeness marker shouldn't be added — it would come off as unnatural if you used them to relay a summary.