When you were a wee one, did you dream of being a doctor or a lawyer when you grew up? Or maybe something even more ambitious like an astronaut? How about a shamaness-queen? Almost 2000 years ago, Queen Himiko of Yamatai raised the bar for women everywhere when she was crowned high priestess and supreme ruler of her kingdom. As the political and religious leader of the proto-Japanese federation of Yamatai, she was beloved at home for her peaceful rule and respected abroad for her diplomatic savvy.

Himiko (also known as Pimiko) is not just any old badass chick in Japanese history. She holds the distinct honor of being the first badass chick in Japanese history. In fact, she's the first named and confirmed (male or female) figure in Japanese history, period. Most people on earth who lived and died during the 3rd century have been rendered anonymous by temporal and cultural distance. But not the queen. According to a recent survey by the Ministry of Education and Sciences, 99% of Japanese schoolchildren recognize and can identify her. Like Oprah or Madonna, Himiko's on a first name basis with the Japanese general public. Meanwhile, she continues to fuel intense debate among amateurs and scholars alike concerning the exact location of her kingdom, a debate that more or less hinges on the location of her grave.

- Before Japan Was Japan

- Chinese Records of Queen Himiko

- Queen Himiko's Legacy: From Hero to Zero and Back

- Himiko Today: Town Mascot, Role Model, X-Rated Fantasy?

- What's So Great About Queen Himiko?

Before Japan Was Japan

Himiko's reign roughly spanned the first half of the 3rd century, long before the Japanese islands were the single political entity that we now call Japan. Rather, the archipelago was scattered with hundreds of "countries" or clan-nations linked into regional confederations. Agricultural communes had started giving way to diversified kingdoms. Political power became increasingly consolidated and social status increasingly stratified. Historians and archeologists often refer to these decades as a "transitional era" between the Yayoi (300BC-300AD) and Kofun (250-538AD) periods—hence the overlap in dates.

What qualified someone to rule one of these emerging kingdoms? Well, it helped if you were on speaking terms with the gods, or at least could convince other people that you were. As in many other ancient (and not so ancient) societies, religious authority was linked to spiritual authority in 3rd century Japan. Luckily for Himiko, female shamans were highly regarded in the folk religion and proto-Shintoism of the time, considered to be capable of banishing pesky malignant spirits on the one hand and speaking on behalf of divine spirits on the other. Since women had equal access to the spiritual realm, they also had access to the political realm. So far from being the shamaness-queen, she was likely one of many shamaness-queens.

Another quirky characteristic of the times lent its name to the Kofun Period. At their most basic, kofun are big piles of dirt. Impressively big piles of dirt shaped like keyholes. First constructed in the mid-3rd century, these large earthen mounds served as mausoleums for deceased rulers. They began to appear in the Kyoto-Osaka-Nara region and then spread throughout the archipelago in tandem with the increasing dominance of the Yamato clan. Over 5,200 have been identified so far in a variety of standardized shapes and uniformly staggering sizes. Himiko may have received one of the first such burials. Stay tuned for more about that.

Chinese Records of Queen Himiko

The little we know about the life and times of Himiko has been gleaned from a combination of written Chinese (and Korean) histories along with archeological verification. Before the Japanese began to record their own history, the Chinese did everyone the favor of writing some of it for them. The History of the Kingdom of Wei (297 AD) stands alone as the first written source about Japan. However, at that time Chinese historians relegated information about the "Land of Wa" (their name for Japan) and its peoples to the flattering "Accounts of the Eastern Barbarians" section of their histories, almost as an afterthought. At any rate, it's got lots of juicy information about the shaman queen and her kingdom. Later Chinese dynastic histories reiterated and confirmed the information included in this first history, and the oldest surviving Korean text (Historical Records of the Three Kingdoms, 1145 AD) briefly describes Himiko's relationship with the Korean peninsula. Collectively, this is what they can tell us:

During the second half of the 2nd century (ca. 147-190 AD), the lack of a capable leader plunged the Land of Wa into political turmoil and violent upheaval. Finally, in 190 AD the unmarried shamaness was chosen by the people to rule. Installed in a palace with armed guards and watch towers, she was served by "1,000" female attendants while her "brother" acted as a medium of communication, transmitting her instructions and pronouncements to the outside world. After ascending to the throne, she went on to restore order and maintain peace like a boss for the next 50 or 60 years.

In addition to upholding her religious duties, Himiko presided over more than 100 "countries" that acknowledged her as their ruler. But she didn't just stay in her own backyard. On behalf of the entire federation of Yamatai, the shamaness queen dispatched diplomatic missions to China at least four times during her reign. In recognition of her legitimacy, the Chinese Wei Dynasty bestowed upon her the title "Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei" along with a nifty golden seal and over 100 ceremonial bronze mirrors. I know that might not seem very exciting now, but back then mirrors were THE ULTIMATE status symbol. A decent stash of mirrors could turn you into the coolest kid on the block.

Unfortunately, the party couldn't last forever. In 248, Queen Himiko died. Some uppity dude reportedly attempted to succeed the throne in the wake of her death, but his reign was heavily resisted and short-lived. According to Chinese sources, order was restored again only once the 13-year-old Queen Iyo took the throne—who just so happened to be her relative. I guess badassery ran in the family.

But that's not all. In Himiko's honor "a great mound was raised, more than a hundred paces in diameter" and 100 of her attendants, um, euphemistically "followed her to the grave." The aforementioned "great mound" was almost certainly one of the first kofun ever erected. Just a few years ago in 2009, a group of Japanese archeologists claimed that they had identified the great shamaness queen's tomb as the Hashihaka Kofun in Sakurai City near Nara. Radiocarbon-dated artifacts found on the periphery of the Hashihaka Kofun date to between 240 and 260 AD. In other words, the time of Himiko's death. Unfortunately, the Imperial Household Agency has designated Hashihaka a royal tomb and thereby forbids further excavation, so we may never know with certainty.

Queen Himiko's Legacy: From Hero to Zero and Back

Truth be told, Himiko didn't have much of a legacy until the late Edo period (1600-1868). How did such badassery go unrecognized for so long? Well, in large part this is because she was conspicuously snubbed in the first Japanese texts, the mythic Kojiki (712) and the mytho-history Nihongi (720). Neither shamaness queen nor her kingdom are mentioned in either, despite the fact that the writers of the Nihongi clearly reference and cite the Chinese histories where she appears. Did they just skip those pages or something? Scholars attribute this blindness to the fact that the 8th century Japanese ruling house was consciously emulating patriarchal Chinese ideals and institutions. And this ideological framework didn't leave much room for the existence of shamaness-queens. Meanwhile, the Japanese adoption of Buddhism and Confucianism didn't do much to elevate the status of women, either. So in the interest of looking cool by Chinese standards, the Japanese court just decided to pretend the great shamaness queen and her ilk hadn't existed.

Luckily, she wasn't permanently erased. Queen Himiko and her kingdom of Yamatai resurfaced during the Edo period with the work of philosopher-statesman Arai Hakuseki and scholar Motoori Norinaga. Between the two of them, they started one of the oldest and most heated controversies in Japanese scholarship: where was the queen's kingdom of Yamatai? Hakuseki rejected the Japanese histories as inaccurate, threw his weight behind the veracity of the Chinese records, and claimed that Yamatai had been in the heart of Japan—the Kyoto-Osaka-Nara region known as the Kinai Plain. Norinaga, on the other hand, rejected the Chinese histories as inaccurate, upheld the veracity of the Japanese histories, and went so far as to claim that the queen's kingdom of Yamatai had merely fooled the Chinese government into thinking that they were the ruling clan.

Norinaga's view became dominant throughout the ensuing decades from the Meiji era through the end of World War II. During this time questions about Himiko's kingdom became tangled with the nationalist-imperialist politics of the day. With the emperor enshrined as divine, rejecting the ancient Japanese histories could be viewed as an attack on the imperial system in general—and some historians who refused to conform lost everything at the hands of censorship laws. One such professor was Naka Michiyo, who from 1878 until the end of his life continually criticized the chronology of the ancient histories and disproved Norinaga's claims about Yamatai.

In the post-war era, historians and archeologists picked up where Naka Michiyo left off, digging into the ancient texts as well as various archeological sites. Between 1955 and 1964, a series of archeological discoveries ignited the debate about the location of Yamatai—including the excavation of a tomb near Kyoto with numerous bronze mirrors possibly dating from the 3rd century. The 1960s through the early 1970s witnessed what the media proclaimed as a "Yamatai boom" as the debate became a national obsession ping-ponging between claims for Kyushu and the Kinai. Suddenly everyone was clamoring to claim Himiko.

Himiko Today: Town Mascot, Role Model, X-Rated Fantasy?

In life Himiko was a religious and political leader. In death she's become just about everything else. As a historical figure, she's turned out to be remarkably pliable, probably because so little is known about her and the little that is known about her creates such fertile soil for the imagination. As a result, she's been repurposed and repackaged in all sorts of ways. For example…

Thanks to the debate over the location of Yamatai, several cities in Japan claim her as a sort of town mascot. In Kyushu, there are statues of her outside Kanzaki Station, near Miyazaki Takachiho Gorge, and on the grounds of the Himiko Shrine in Hayato.

The city of Yoshinogari holds an annual bonfire festival that climaxes with the appearance of a costumed "Himiko" and a Kyushu brewery released "Himiko Fantasia" shochu.

Over in the Kinai region, Sakurai City (where Hashihaka Kofun is located) features the shamaness queen on signs, online, and in person (well, at least a person in a mascot costume). City leaders have created online Himiko-themed anime shorts, and there's a municipal webpage devoted to her called "Himiko-chan's Page."

As a role model the shamaness queen can symbolize female power, innate occult abilities, national origins, and even good eating habits. No kidding, she's the poster girl for a school campaign that urges students "to chew your food as thoroughly Queen Himiko did" in order to improve digestion and tooth health.

You can even be crowned "Queen Himiko" by participating in one of a number of Queen Himiko Contests, which are more or less beauty pageants. Women 18 and older are eligible to compete for a substantial cash prize on the basis of their charm and appearance—which is a bit depressing when you consider Queen Himiko's historical worth probably had nothing to do with her ability to put on eyeliner.

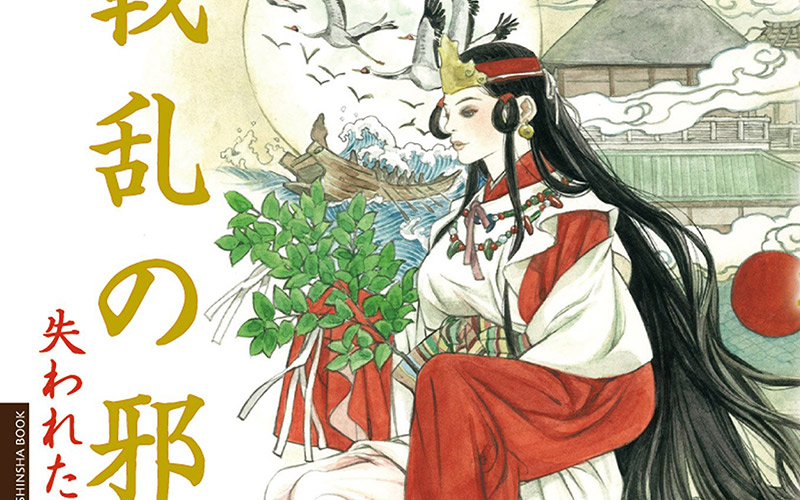

Himiko has also served as the inspiration for characters in numerous films, novels, manga, anime, and video games. A powerful and dignified shamaness queen rules with authority and grace in the 1967 bestseller "Maboroshi no Yamatotaikoku." The 2008 film version of the book starred a venerated Japanese actress as the Queen Himiko, and her image in the role was selected for a set of commemorative stamps by the Japanese government.

And then for something entirely different, an irresponsibly promiscuous queen meets her downfall in the 1974 film drama "Himiko" directed by Masahiro Shinoda.

In addition to a symbol of female power (whether for good or ill), Himiko has also been used as a tool for political critique. The first book of manga maven Osamu Tezuka's acclaimed Phoenix series depicts a vain, power-hungry queen as the first of many vain, power-hungry rulers throughout Japanese, and world history—"power leads to corruption" being the main theme that Tezuka pursues throughout the rest of the series. And one of Kobayashi Yoshinori's political cartoons features her in order to argue for changing the imperial succession laws to allow for the throning of an empress.

Himiko pops up all over the place. A clone of the queen appears in the manga Afterschool Charisma and in the anime Shangri-la. The 2013 Tomb Raider video game reboot features a menacing Himiko as its primary antagonist. She's the "Queen of all Nippon" in the Zelda-like video game, Okami. The Legend of Himiko encompasses an anime, manga, and video game series that appeals to pre-teen girl power sensibilities. And for the 18+ set, Taniguchi Chika's erotic manga series aimed at women stars none other than Queen Himiko in various X-rated adventures. So whether you're looking for a despotic villain, a role model, a symbol of national or local identity, a naïve shrine attendant, or a sexual fantasy, there's a Himiko out there for you.

What's So Great About Queen Himiko?

Himiko ruled a kingdom 2000 years ago, fuels a bunch of debate about said kingdom, and continues to get a lot of face time in modern Japan in the form of statues and stamps and just about everything else. As impressive as all that is, what makes her noteworthy is that she wasn't unique in her time. In the earliest periods of Japanese history, women more generally had public authority, economic power, and spiritual prestige. The historical figure is merely representative of the heights of the political and religious leadership that women in Japan held prior to the importation of Chinese, Buddhist, and Confucian ideology. And even after these patriarchal influences first took root, it was many decades (centuries, even) before ideology and practice fully merged (if indeed they ever did).

In other words, Himiko was not an anomaly. She was merely the first notable ancestor of a strong tradition of female religious leaders (a la miko priestesses in Shinto) and political leaders (a la empresses) in Japanese history. Over time women's roles may have devolved from active initiators to assistants in both spiritual and secular realms. But Himiko serves as a shining example that symbolically reflects the many other (now anonymous) women who were also leaders in their communities.