Working hard is not enough. To succeed, you have to let go of fear.

Higuchi Ichiyō is considered one of the most influential writers of the Meiji era. Her stories are held as groundbreaking masterpieces. And her face is on Japan's 5000 yen note.

But she didn't achieve this through sheer will or hard work. She was also fearless. Circumstances, setbacks, tragedy, and the world around her gave her plenty of reason to fear. But she found a way to overcome it, and achieve more in her short life than any man of the Meiji period.

The Meiji Period: Higuchi Ichiyō's World

Everything in Japan was flipped on its head in the early Meiji period (1868 - 1912). The shogun gave up his power to the Emperor. The class system that put the samurai class above everyone else was abolished. And the country ended its long standing isolation from the rest of the world.

Japan as a whole felt like it had fallen behind and the only way to catch up was to modernize, and fast. The government sent out groups of scholars to bring back technology, political ideas, language, and everything else they could get their hands on to turn Japan into a modern mishmash of the best parts. This flood of new technology bombarded the Japanese people, forcing them to play catch-up while the country reinvented itself.

And for women, this did a few really harmful things.

Education

Revisions to the educational system crippled girls compulsory education. Not only was the education provided to girls embarrassingly lower than that given to boys, but they were only required to attend six years of school.

Suddenly people were arguing that an education would make girls misbehave. They said women didn't need schooling if they were going to do their duty as mothers.

Pressure to turn women into "Good Wives, Wise Mothers" 良妻賢母 in order to make Japanese citizens loyal, hardworking, and dedicated, put women's place at home helping raise children and industrialize the country.

Conservatives attacked Christianity, which honestly wasn't new for them, and forced the closing of schools that taught religion. This destroyed the missionary schools that were teaching girls a better, higher education than those set up by the government.

Suddenly people were arguing that an education would make girls misbehave. They said women didn't need schooling if they were going to do their duty as mothers. Therefore an educated woman wasn't going to help the country. Instead, they should be home taking care of the household.

Social Standing

After finishing school, things didn't get better for women as they got older. Once they were married, they had pretty much no rights whatsoever.

A married woman in the Meiji period was considered the property of her husband. The head of the household, her husband or father, had all the power.

He would make most of the decisions for all the family members — whom they should marry, where they should live, whether they could adopt children, and so forth. Wives had almost no legal authority, and since marriage was perceived as a transaction between families, the groom's family sometimes did not register a marriage until the bride proved to be capable of adjusting to her husband's family. — Yukiko Tanaka

Because women were legally considered to be property, this led to a rise in prostitution. Female prostitutes were licensed and worked in houses under contracts. They usually had a certain amount of debt on their contract and would work for the house to pay it off. This kept it from being considered slavery, which was illegal according to the new Meiji Constitution.

The idea that women could be easily and openly bought with money was a substantial impediment to men's seeing women as their equals. Over many years, Confucian ideology had instilled a certain mistrust and contempt toward women in men's minds, and now Meiji men perpetuated another inheritance that hobbled social progress by their socially sanctioned practice of selling and buying women. — Yukiko Tanaka

Not only that, but men could still have mistresses along with their wives. And when women tried to do something about it, they discovered that the people in power within the government who they needed to convince, were men who supported the practice more than anyone.

Who Am I?

Another thing you need to be aware of is the idea of the "individualism." Briefly put, it's a focus on the thoughts, needs, and wants of the individual rather than of a larger group (in this case, the nation of Japan). The idea that people were individuals whose needs could matter more than that of the groups they belong to did not exist yet in Japan. They were a collectivist society, one that gave importance to groups specifically, instead of the individuals in said group. If you've studied Japanese, you've probably come across in-group/out-group concepts and these ideas are very much intertwined.

Individualism: a focus on the thoughts, needs, and wants of the individual rather than of a larger group.

There is a crazy amount of research on the subject of Japanese collectivism vs Western individualism, which cover much more than I'm saying here, so please check them out if you're interested in learning more.

Now we end up in a world where women are forced to take a step back in a country that was forging ahead at an incredible pace. This is the world Higuchi Ichiyō was born into, and the world of her characters.

Growing Up Poor: Higuchi Ichiyō's Early Life

Higuchi Ichiyō was born as Natsu, or Natsuko, in Tokyo when it was still called Edo in 1872. Her father and mother had moved to Edo from the country before she was born to find success in the city. Her father had worked hard to buy the rank of a lowly samurai and everything seemed to be looking up. Unfortunately for them, almost immediately after he got it, the rank lost all meaning thanks to the removal of classes in the Meiji Restoration.

He eventually found work as a low ranking member of the local government, but the family was never able to find financial stability again.

Struggles of A Young Girl

Higuchi Ichiyō was a bookworm. She was shy, quiet, and poor. She read stories about heroes going on adventures and fighting villains and doing exciting things. She wanted to be a hero and do something important with her life. But being born in Meiji Japan made that difficult, if not impossible.

Elementary schools had just been introduced in Tokyo when she was a baby, but as we now know, they were more focused on making girls into productive members of society than giving them a proper education.

Though Ichiyō received top grades, her mother pulled her out of school after the required six years, believing the ever popular idea that schooling wasn't becoming of young women. Her father, however, bought her poetry books and a private tutor to help her study. He was well educated himself and wanted his daughter to be well educated too.

When Ichiyō was fourteen, her father helped her enroll in a private school called Haginoya, run by a woman named Nakajima Utako. She studied waka poetry and the Heian classics: The Kokinshū, The Tale of Genji, and The Tales of Ise.

Although she was at the top of her class, her classmates were the daughters of rich, important people. For them, it was a finishing school, but for Ichiyō it was much more. She never felt like she fit in and this pushed her to focus intensely on her schoolwork. As a result, she was consistently at the top of her class and won many poetry composition contests.

Tragedy

When Ichiyō was sixteen, her father and older brother passed away from tuberculosis. Her other brother had been disowned years earlier. This left her as head of the household and caretaker of her mother and younger sister.

This was a pretty unique position for a woman of the Meiji period. As we know, women were legally considered the property of their father or husband, but Higuchi Ichiyō was a young, single woman put in charge of herself and her family.

When Ichiyō was sixteen, her father and older brother passed away from tuberculosis. This left her as head of the household and caretaker of her mother and younger sister.

Before her father had passed, there were talks about her engagement to a well-to-do law student. However, once he realized how poor they were, he left; a huge betrayal to the Higuchi family.

Because her mother hadn't allowed her to continue school, she wasn't qualified to work as a teacher, even though the opportunity existed at Haginoya. They borrowed money from family and neighbors and took in cleaning and sewing work to make ends meet. The only other options for women to make money at the time were prostitution or becoming the mistress of a rich man.

Work to Live, Live to Work

Ichiyō had been writing in a private diary for years as a way to hone her skills and express her thoughts while attending school. So when a classmate from Haginoya, under the pen name Miyake Kaho, became famous for publishing a novel, she decided to try making money writing fiction.

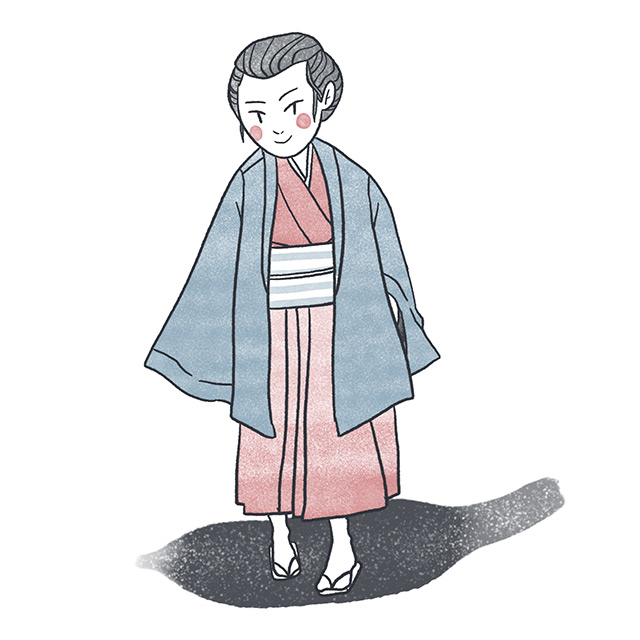

She wrote her first novel at the age of twenty under the pen name Ichiyō 一葉, or "floating leaf," and continued writing for the next four years. But she constantly struggled with separating writing for art and writing for money.

It was extremely hard on her. She would agonize over her work, and even though her family was struggling to make ends meet, she refused to publish work she wasn't satisfied with.

In the afternoon I sat at my desk and, somehow or other, I was engaged in writing. However, for various reasons I got disgusted. I have already torn up my manuscripts about ten times. It is really strange that I haven't even completed a new story… I can't go on like this forever, and so I start writing anew thinking up another plot; but none is good enough. Every time I read famous tales and novels, both ancient and modern, I become distressed over my own writing and finally I begin to feel like giving up. However, perverse as I am, I can't give it up quite so easily, and presumptuously enough, I have started writing again. I must, by all means, complete it by day after tomorrow. I feel that I will die if I don't finish it. If people wish to laugh at my faint heart, let them laugh! — Higuchi Ichiyō, translated by Hisako Tanaka

Although she knew she could write faster and churn out a product that would make money, she couldn't force herself to publish anything she wasn't proud of.

It had been nearly one year since I began writing novels. I have published none yet, and none satisfies me. My mother and sister blame me repeatedly by saying that I am weak minded and always retrospective… Even though I write for our livelihood, what is poorly done would seem poor to anyone's eyes. Once I have claimed myself as a writer, I would dare not write anything that may be thrown into a waste basket after being read once, as is the case with the majority of writers. People today are frivolous, and what is welcomed today may be discarded tomorrow in a world like this, but if I appeal to the genuine feeling of the people, and if I depict genuine feeling, even though it may be a fictitious writing by Ichiyo, how could it be without value? I do not desire a brocade gown nor am I after a stately mansion. How could I ever stain my name which I wish to leave behind for a thousand years for the sake of temporary gain? I will rewrite even a short story three times, and then I will ask the world to pass judgement. In spite of that, should my efforts be lost as a mere waste of paper and brush, still I would take it as heaven's decree. — Higuchi Ichiyō, translated by Hisako Tanaka

With the stress and disapproval from her family, not to mention the numerous societal pressures, it's amazing she managed to continue at all.

The Road to Success

Getting published in the Meiji period wasn't particularly difficult, but getting an "in" would require a mentor. Someone who was already established in the literary world. This is where Tosui Nakarai came in.

Ichiyō came to him asking for help, and with time, unexpectedly found herself attracted to him. They were both uncomfortable around one another, considering the social implications of a man and a woman who were not related spending any time together. Though he did eventually help her publish the first of her short stories through a literary journal.

"I would dare not write anything that may be thrown into a waste basket after being read once… but if I appeal to the genuine feeling of the people, and if I depict genuine feeling… how could it be without value?"

— Higuchi Ichiyō

However, soon rumors began to spread, particularly around Haginoya, where Ichiyō had been working as a teacher's aid. Soon Nakajima Utako approached her, revealing the rumor that was following her: Tosui was telling people that the two were sleeping together.

Shocked and offended, Ichiyō was forced to cut off contact with him to save face and her career before it spread. This, along with her broken engagement plans, gave her a realistic and bitter outlook on love, and heavily influenced her writing.

Female friends and writers, including Miyake Kaho (the woman who inspired her to write for money in the first place) and Nakajima Utako helped her make new connections in the literary world, including a group called Bungakkai (The Literary Circle).

She continued to work hard and made money off of her publications, but her need to create quality content and refusal to make anything subpar crippled her income.

Eventually she got so fed up with this struggle between art and money, that she moved the family to a little shop near the pleasure quarters of Yoshiwara. There they opened a store that sold knick knacks, small wares, and candy. Though the shop became popular, they weren't able make a profit and they were forced to move only ten months later. But it's astonishing that a single woman in her early 20s during the Meiji period was able to do this at all.

She continued to write after the business failed, but her experiences in the pleasure quarters had a huge impact on her writing, and ended up inspiring what is now considered to be her masterpiece.

Short Stories

In her lifetime Ichiyō wrote 21 short stories, thousands of poems, and a multi-year, multi-part diary, which many people argue is a piece of art in its own right. But what is it about her writing that made her so famous and so memorable?

First of all, most of her main characters are women; almost always poor, almost always in a situation that is completely out of their control. She wrote about orphans, divorcees, children, and prostitutes. She wrote in a way that is painfully realistic. No one is "saved" or whisked away in some sort of fairytale ending, and most of her stories end without any kind of real closure.

She took inspiration from the Heian classics she studied in school, and later, Ihara Saikaku, who was famous for writing about the common people of the pleasure quarters during the Edo period. And of course, she took inspiration from her own experiences as a woman living in Meiji Japan; being spurned by the men in her life, living below her means, being unable to control her own destiny, and especially from her time in Yoshiwara.

As she grew as a person, she grew as a writer. Her first works were overly flowery, relying heavily on Heian language and motifs. But they slowly transformed into strong representations of the people living in the Meiji period; of the time she was alive and of the struggles of the downtrodden. She stopped focusing on pretty words and shifted into trying to represent the world around her; merging a beautifully written style with allusions to the Japanese classics and problems of the modern day.

But it's important to note, that in all her writing about women and their unfortunate situations, she never said anything revolutionary.

What I mean by that is she didn't write about women who tried to fight back, or change their situation. She wasn't calling out for political or social change. And she wasn't among the early feminists of her time, though they did exist. She never crossed the line past "good wife, wise mother" and instead, was able to express the pain and sorrow of women, children, and the poor without blaming the system that put them there.

Because of this, her male contemporaries saw her as, "a writer who beautifully told the sad stories of women," (Yukiko Tanaka) and not as one of the feminist writers they saw as an annoyance. Whether this interpretation was something she would have agreed with, we can't say. But if she had been received differently, we might not be remembering her today.

To sum it up nicely:

Her motive to write stories was not simply to emancipate women from the oppression of men, as is often argued of women writers in early modern societies; it is more complex: she wanted to write because she knew her writing skills were much more sophisticated than those of her peers, whether male or female. But she also needed to write for practical reasons; she needed to make money in order to support her family as the registered head of the household. - Kyōko Ōmori

Let's look at a few summaries of her most popular stories to get a better idea of what she was really writing about.

The Thirteenth Night 十三夜

Oseki is a woman from a poor family who is married to a rich, well connected man. The marriage helps support her family and improve their standard of living, as well as find a job for her younger brother.

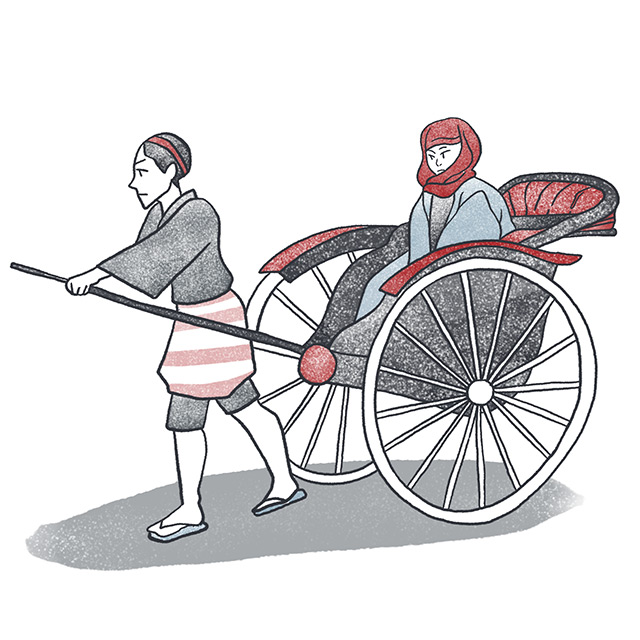

The story opens with Oseki taking a rickshaw late at night to her parents' home, on the thirteenth night of the ninth month of the lunar calendar (one of two special nights for moon viewing). She overhears them talking about how wonderful her marriage has made their lives and how thankful they are for the match. This makes her hesitate because she's come to tell them that she is planning to leave her husband and young son because of the mental abuse from her husband.

She finally goes in and admits why she has come. About how her husband may have married below his social standing, but he was the one who found her, who courted her, and convinced the family of the choice. But once their son was born he's done nothing but hurl insults and tell her she's worthless, stupid, and uneducated every time he sees her.

Higuchi Ichiyō wrote in a way that is painfully realistic. No one is "saved" or whisked away in some sort of fairytale ending, and most of her stories end without any kind of real closure.

Once everything is revealed the family laments together. Her parents agree that the situation is a bad one, and they don't blame her for seeking them out and wanting to leave. But they explain that she must go back to her husband for her son's sake.

You see, in the Meiji period you could get a divorce, but the woman would not be able to get custody of her children. A divorce would mean abandoning her son to her abusive husband and leaving him alone to grow up under a step-mother or mistress.

She makes up her mind, with the support of her parents, to go back to her home and live out her life for her son and forgo any happiness of her own.

It was selfish of me to think of a divorce. You're right. If I couldn't see Tarō, there'd be no point in living. I might flee my present sorrows, but what kind of future would I have? If I could think of myself as already dead, that would solve everything… Then Tarō would have both his parents with him. It was a foolish idea I had, and I've troubled you with the whole unpleasant business. From tonight I will consider myself dead — a spirit who watches over Tarō. That way I can bear Isamu's cruelty for a hundred years to come.1

She leaves to go home in a new rickshaw and discovers that it's being pulled by a man she once knew when she was young and living in the poor neighborhood. They bitterly reflect on their situations and finally Oseki heads back to her home to start living a life in misery for the sake of her son.

Separate Ways わかれ道

This is a very short story about a woman named Okyō and a young boy named Kichizō. Okyō has recently moved into the poor quarters where she befriends Kichizō: a short orphan who's always getting into trouble and isn't very popular among the other kids in the neighborhood. His time spent with Okyō calms him down and helps him feel like life isn't so horrible as long as you have someone to share it with.

But one day he finds Okyō packing up her things to move. She explains that she's going to become a man's mistress and she won't be seeing him anymore.

"Oh, dear," Okyō sighed. She stopped walking. "Kichizō, I'm sick of all this washing and sewing. Anything would be better. I'm tired of these drab clothes. I'd like to wear a crepe kimono, too, for a change—even if it is tainted."

She tried to calm him down but he's too disgusted to listen to her and speaks openly about how hard his life has been so far. Her leaving feels like a betrayal. Finally the story ends with this passage:

"You're too impatient. You jump to conclusions."

"You mean you're not going to be someone's mistress?" Kichizō turned around.

"It's not the sort of thing anybody wants to do. But it's been decided. You can't change things."

He stared at her with tears in his eyes.

"Take your hands off me, Okyō."

Child's Play たけくらべ

By far, her most famous and decorated work, Child's Play is centered around the interactions between two groups of youths living in Yoshiwara. They're split between two street gangs of kids (in their early to mid teens), one led by Chōkichi, a selfish, loud kid, and the other Shōta, a similarly loud kid who happens to be well-liked by most of the neighborhood.

But the part of the story that everyone focuses on is the relationship between two young people on opposing sides.

Midori is a young girl who is living at the brothel house where her sister works as a prostitute. She's beautiful, spoiled, and very confident in herself. The people who live with her give her an exorbitant allowance and she always has extra money to give to her friends and spend on frivolous things. This attention is most likely the result of the proprietress's guilt about the girl's inevitable future, and Midori's carefree nature a lack of knowledge to her fate.

Nobu is around the same age and lives with his rich family at a temple, and he is destined to become a monk like his father. Chōkichi asks him to join his gang for the power it will bring to the group.

Though the story follows a conflict between the groups run by the two head boys, throughout it, there is obvious tension between Midori and Nobu. It's hinted that the two are in love with one another but because of their positions in life, more so than their groups of friends, they are never able to express their feelings or even look directly at one another. Instead they are left acting like they hate each other.

At the end of the story, Nobu is sent off to training and has to leave his friends. Midori no longer goes out and plays with everyone else, she's changed; she's more ladylike, quiet, and not so happy-go-lucky. Scholars argue that this probably means she either, 1. got her first period and is of age to become a prostitute like her sister, or 2. was "initiated" into her position as a prostitute with her first client. Either way, it's changed her forever.

Most of the kids in the story are oblivious to the impending doom surrounding Midori and Nobu, and it's touched upon quite a few times, especially in regards to Midori's fate.

In one scene Shōta, arguably Midori's closest friend, is talking to another boy in his gang and reveals to the reader that things aren't as nice as they seem:

"Oh, Midori, she went by a little while ago. I saw her take one of the side bridges into the quarter. Shōta, you should have seen her. She had her hair all done up like this." He made an oafish effort to suggest the splendor of Midori's new grown-up hairdo. "She's really something, that girl!" The boy wiped his nose as he extolled her.

"Yes, she's even prettier than her sister. I hope she won't end up like Ōmaki." Shōta looked down at the ground.

"What do you mean—that would be wonderful! Next year I'm going to open a shop, and after I save some money I'll buy her for a night!" He didn't understand things.

"Don't be such a smart aleck. Even if you tried, she wouldn't have anything to do with you."

"Why? Why should she refuse me?"

"She just would." Shōta flushed as he laughed. "I'm going to walk around for a while. I'll see you later." He went out the gate.

"Growing up,

she plays among the butterflies

and flowers.

But she turns sixteen,

and all she knows

is work and sorrow."

He sang the popular refrain in a voice that was curiously quavering for him, and repeated it again to himself. His sandals drummed their usual ring against the paving stones, as all at once his little figure vanished into the crowd.

The severity of her situation hadn't been lost on him, but the story doesn't dwell on it. Instead, it continues on and simply tells what happens to these kids and how their happy lives are inevitably about to change for the worse - and there isn't anything they can do about it.

Uramurasaki うらむらさき

One of her last stories only consists of one chapter and is about a woman named Oritsu, who is married to a rich man who pays for everything she could need. He's kind to her and loves her, but she cheats on him with a young man named Yoshioka anyway, out of her need for emotional fulfillment.

In the beginning we see her lie to her husband, saying she is going to visit her sister, when really she's going to meet with her lover. Once she's on her way she stops and thinks about her actions and how they will affect the people around her, specifically the life of the young man she's sleeping with and how being discovered could ruin both of their lives.

In the end, she decides to continue the affair and heads towards her lover's home, smirking as she walks.

Impact and Reception

She hated being treated as if she were something unique and special simply because she was a woman. She wanted her peers to point out her flaws and help her improve, not marvel at her like some kind of circus act.

You couldn't be a writer back in the day without being involved in a literary circle. There weren't any message boards or group chats to get people together, but there was mail and literary journals. After she joined the Bungakkai, the young men of the group looked up to and admired Ichiyō for her skills. She was like an older sister to them, and the contacts she gained helped her find new publishers and help with her own writing.

While her works were extremely well received, she was never satisfied. And the problem of being a woman who wasn't taken seriously, continued to plague her.

…Of all the visitors I receive, nine out of ten come merely out of curiosity, because they find it amusing that I am a woman. That is why they praise and congratulate me as a "modern Sei Shonagon" or a "modern Murasaki Shikibu," even when I only produce scratch paper. They do not have enough insight to fathom my deepest thoughts, and they only delight in the fact that I am a woman writer. Thus they reveal nothing in their criticism. Even if there are flaws in my work, they cannot see them. They merely say, "Ichiyō is good," "she is skillful," and "her skills even exceed those of male writers, not to mention other female writers," and "indeed, she is good and talented." Besides such empty phrases, can they find no other words to say? Can they not see any flaws in my work to criticize? This is indeed a strange phenomenon. - Higuchi Ichiyō, translated by Kyōko Ōmori

She hated being treated as if she were something unique and special simply because she was a woman. She wanted her peers to point out her flaws and help her improve, not marvel at her like some kind of circus act. And to add some present day context, the essay this is from comes from a larger book called The Modern Murasaki! How hard do you think she'd roll her eyes at that bit of irony?

Even the other famous writers of the time couldn't get past the fact she was female. Mori Ōgai and Koda Rohan wrote a review of what was to become her most popular short story, all but calling her a writing goddess:

What is amazing is that the characters which appear in this story are not those beastlike human beings frequently depicted by Zola and Ibsen, whose technique the naturalist writers tried to imitate to the utmost, but they are real human individuals who laugh and cry with us… Even though I may be derided by the world for worshipping Ichiyō, I do not hesitate in conferring the title of ‘real poet' upon this person… - Mori Ōgai

Then, in the same review, Koda Rohan added:

…I feel like making pulls out of some words in the story and let a great number of critics and novelists of our day take them as a magical formula to improve their ability in writing… - Koda Rohan

Even if she was good, which she was, she knew their praise was over the top, and it infuriated her.

Digging Deeper

Her contemporaries knew she was good but never seemed to be able to explain why, other than the typical, "gee whiz look what this lady did!" Which means it's up to more modern scholars to explain what exactly made her so special and why we still remember her today.

The cultural significances of telling the stories of those who had no voice: women, the poor, and children, was big enough to warrant praise on its own, but there's more she did.

I think it will help to look at some more modern analysis of Higuchi Ichiyō's works:

She is representative of women who thrived (though briefly) without being discouraged by gender barriers and poverty, as well as a symbol of Japan's literary achievement in the early modern period. - Kyōko Ōmori

The most remarkable quality of her fiction was its skillful combination of elegant classical language and classical references with an acute depiction of the class and gender distinctions that underpinned Meiji society. - Sharalyn Orbaugh

Not only the first woman writer of distinction for centuries but… the finest writer of her day. - Donald Keene

Through her dedication to her art, Ichiyō succeeded in creating a literature of her own, thus paving the way for the generations of women writers who were to follow. - Margaret Mitsutani

Cut a wide swath through Meiji letters. Her grasp of high Heian, her love of low Edo were almost legendary, but she was still sui generis. In her bold and idiosyncratic style, she had rediscovered a way to be serious in fiction, something nearly two-hundred years' worth of writers had forgotten. She returned the novel to the province of the heart. - Hisako Tanaka

Like a shooting star, Ichiyo shone brightly for a moment, then disappeared. Some cherished her work because of its lyrical and nostalgic quality; for them she was "the last woman of the old Meiji." However, a close examination of her fiction — particularly the later works — reveals that Ichiyo was more than a writer who depicted the sad fate of Meiji women beautifully and with resignation. A protest against the men's domination of women is in her fiction… - Hisako Tanaka

In subject, setting, and theme Ichiyō had limited herself, but there were no shackles on the emotional range or literary effect of her stories. It was revolutionary of Ichiyō to see dignity and pathos in the unhappiness of children, and to make of this apparent trivia a metaphor for the drama, so new to Japan, of the sudden, confusing attaining of selfhood. - Robert Lyons Danly

What's So Great About Higuchi Ichiyō?

People look to Higuchi Ichiyō as an example of what Japanese literature can be; a beautiful mix of style, language, and an accurate portrayal of the lives of Japanese people while still including allusions to old Japan.

You might be wondering why she only wrote a little over twenty short stories. I'm sorry to say, it's because she passed away in 1896, at the age of twenty-four. She had become extremely popular and was making money from her writing. But she contracted tuberculosis, like her father and brother before her, and was forced to stop writing a few months before her death.

Her short life, along with the novelty of her status as a female writer during the Meiji period, added to her popularity and mystique. But by now you can see that her stories stand on their own, even without the buzz surrounding her circumstances.

She wrote about Japanese women in a realistic, beautifully sad way. She went from telling the stories of abused women who had no choice but to stay with their abusers, and a little girl who learned the hard truth about growing up under a prostitution contract, to women who were able to make their own choices. She wrote about women like Okyō, who made the decision to become a mistress to escape poverty. It may not have been an ideal choice, but it was a choice she made on her own. She wrote about women like Oriki, who came to a literal crossroads: to stop doing what she wanted, or to defy her husband and society and continue seeing her young lover, and she chose the latter. This was a hint of individualism about to sneak its way into Japan.

Higuchi Ichiyō spoke for the women of Japan in a way that was true and beautiful. Tragic, but subtly strong.

"Not only the first woman writer of distinction for centuries but… the finest writer of her day."

— Donald Keene

If you're interested in reading Higuchi Ichiyō's works for yourself, Robert Lyons Danly has a wonderful collection of translations, as well as a very in depth history of her life, in the book In the Shade of Spring Leaves. If you'd like to read her work in Japanese, Aozora Bunko has them online for free in both the original kobun format and some modern Japanese translations.

There is also a tour you can take in Tokyo called "In the footsteps of novelist Higuchi Ichiyo" where you can walk through the Yoshiwara district, temples she visited, her former home, her burial site, as well as the Higuchi Ichiyō Museum. There you can see original manuscripts and a model recreation of her writing desk.

I'll leave you with one final quote. Hopefully it speaks to you the way it spoke to so many others.

"In attempting a venture with all one's heart, discarding worldly desires and being unafraid in all matters of life and death, a woman can achieve as much as a man can." - Higuchi Ichiyō

-

All story excerpts from In The Shade of Spring Leaves, translated by Robert Lyons Danly. ↩