As you might have guessed from the inaugural article in this series, the sword-slinging samurai Tomoe Gozen seems like a tough act to follow. That said, I don't think Murasaki Shikibu has anything to worry about. This 11th century wordsmith single-handedly wrote her way into history as the world's first novelist and one of Japan's most-celebrated cultural heroes. At a time when paper and ink were precious luxury items, people were scraping together every scrap available just for the chance to read her scribbles. If the pen is indeed mightier than the katana, Murasaki could have kicked Tomoe's ass.

Cutthroat Court Life in the Mid-Heian Period

From 794 to 1185–almost four hundred years—the hip and happening city of Heian-kyo (modern day Kyoto) acted as Japan's imperial capital. It was also Murasaki Shikibu's hometown. As the center of the Japanese universe at the time, Heian-kyo lent its name to these four centuries in Japanese history, known as the Heian period (heian jidai 平安時代). Heian-kyo was THE place to see and be seen–anybody who was anybody could be found strolling through those streets (or, more likely, being carried through them on palanquins). When the Fujiwara family dominated court life (from the mid-9th to the mid-11th century), aristocratic government and culture was at its peak. Court members led lives of luxury funded by their estates in the countryside while they looked down upon "the little people" outside the capital. If this sounds a little like our own starstruck Hollywood, it kinda was—with all the glitzy glamour and cutthroat competition that that implies.

So how did Heian courtiers go about trying to win the popularity contest that was daily life? Screw math, science, and standardized tests—an aristocratic education meant learning musical instruments, perfecting your calligraphy, and—most importantly–honing your poetic genius. During the Heian period, poetry was your ticket to both romantic and bureaucratic success, the language of courting lovers and courting imperial sponsors alike. And in their quest to make life imitate art, courtiers followed a cumbersome beauty regimen that turned them into living dolls—in fact, their likenesses live on in the annual nationwide "Doll Festival" (hinamatsuri) featuring replicas of Heian courtiers. Men and women alike painted their faces white, blackened their teeth (that's right, blackened, not whitened), fastidiously styled and scented their hair, and meticulously dressed according to complex color combinations that symbolized everything from social status to weather to season. Basically it was very easy to spend more time getting ready to go out than the time you actually spent out. Sometimes I can barely bring myself to throw on jeans and a t-shirt before leaving my apartment.

On the one hand, these aristocratic families and their pursuit of aesthetic refinement in all areas of life had a positive and permanent impact on the content and quality of Japanese arts and culture. But on the other hand, being constantly pressed by the stringent demands of the courtly cult of beauty must have felt like living in a tabloid. The imperial city was like the red carpet on Oscar night, where the slightest fashion crime or lackluster rhyme could turn you into a royal laughingstock. Foolishly wearing last season's color combinations to this season's party could make you wish you were dead. There was constant scrutiny, judgment, and petty gossip. There was marriage politicking, cutthroat social climbing, and competition for rank at court. There were scandals and drunken revelry galore! Merely falling out of favor with the imperial powers could get you kicked out of court. Rubbing an important someone the wrong way could get you either exiled or banished to the countryside (which were equally terrible fates in the eyes of the courtiers).

All this drama gave capital dwellers a lot to write about—and write they did. It was during these linguistically fertile centuries that both kana systems were developed, radically transforming the course of written Japanese. While Chinese continued to act as the official written language of government (also known as "men's letters" or otokomoji), women churned out reams of kana (also known as "women's hand" or onna-de) that collectively created the first indigenous Japanese literature. Even though Chinese characters would never fully disappear, the kana were here to stay and make all of our lives easier—radically reducing the number of kanji necessary to be literate and completely eliminating the need to use Chinese grammar. So we Japanese language learners have the female nobility to thank for the fact that we don't have to learn Chinese in order to write Japanese. Huzzah!

Murasaki Shikibu From Birth To Death

Roughly around the year 978, Murasaki Shikibu was born into a lesser branch of the sprawling Fujiwara family tree. Her mother passed away not long after she was born, leaving her father Fujiwara no Tametoki (a scholar and minor bureaucrat) to raise his children as a single dad—a highly unusual upbringing at the time. But that was just the beginning of Murasaki's unconventional (at least by Heian aristocratic standards) life. Her insatiable intellectual appetite led her to not only become extremely well-educated, but also to master what was then considered an exclusively masculine subject: literary Chinese. As she reveals in her diary, this skill made her father "sigh and say to me: 'If only you were a boy how proud and happy I should be.'" On top of that, she spent most of her life as a single woman even though the vast majority of women of her status got married at puberty. She also accompanied her father to his four-year governorship posting in "distant" Echizen. What was then a five-day road trip from the capital might seem like no biggie now, but engaging in that sort of long-distance travel was unheard of for aristocratic women at the time. And when she finally did tie the knot, that marriage lasted all of two years (from 999-1001)–an unsurprisingly short period of time considering that she married an elderly cousin destined to die.

This unconventional life culminated in unconventional success. Despite Murasaki's refusal to participate in marriage politics and social climbing, in either 1005 or 1006 Murasaki was invited to become a lady-in-waiting at court to serve Empress Shoshi as a Chinese tutor and resident writer. Residing at court was every little aristocrat's dream, but Murasaki seemed less than impressed with life there. She moved out to a mansion near Lake Biwa with Empress Shoshi in either 1010 or 1012. Most scholars assume that she died around 1014, but there's a contingent that argues she was alive and well in 1025, having retired to a nearby convent at age 50 or so.

Basically, Murasaki Shikibu was too busy being a badass to be normal. Whether she died in 1014 or 1025, Murasaki Shikibu must have had her nose to the inkstone during the majority of her forty or fifty years on earth. Most of what we know about her life comes from her three-year diary and a collection of 128 poems that she left to posterity.

And then there's Genji. All 54 chapters and 400-plus characters of it. Murasaki's masterpiece The Tale of Genji (or Genji Monogatari) is also known as the world's first novel and the "greatest work of Japanese literature." Part-soap opera, part-existential poetry, The Tale of Genji tells (surprise!) the tale of Genji: the fictional son of an emperor and a dead concubine. Genji woos his way around the court like a Japanese Casanova, until karma comes to bite him in the ass and he is exiled to die in obscurity. (belated spoiler alert!)

What sets the story apart from One Life To Live is the narrative's lush descriptions, psychological complexity, and insightful observations of nature and the human condition. Or, as Japan scholar and translator Helen McCollough puts it, the universal appeal of The Tale of Genji, "transcends both its genre and age. Its basic subject matter and setting—love at the Heian court—are those of the romance, and its cultural assumptions are those of the mid-Heian period, but Murasaki Shikibu's unique genius has made the work for many a powerful statement on human relationships, the impossibility of permanent happiness in love…and the vital importance, in a world of sorrows, of sensitivity to the feelings of others." Doesn't sound too bad, eh?

Murasaki Shikibu's Many Afterlives

It didn't take long for Murasaki Shikibu and her writing to reach celebrity status. Before the days of instant online publishing and New York Times' bestseller lists, popular books had the rarity and appeal of rock stars. The Tale of Genji was rabidly popular from the moment it was completed in 1021, obsessively hand-copied and distributed through the provinces within a decade, and hailed as a timeless classic within the century. To get a sense of just how gaga for Genji every literate person was, one 11th century writer wrote a whole passage in her diary about her lust for the copies of Genji in the capital and longing to visit someday, somehow just to get the chance to read it in person. Ever since then, Murasaki and her masterpiece have been compelling audiences to read, study, and write about her life and her art. She's also been inspiring artists to imitate, illustrate, and innovate in new works of their own. As Japanese literature scholar Haruo Shirane observes, "The Tale of Genji has become many things to many different audiences through many different media over a thousand years … unmatched by any other Japanese text or artifact." Don't quite believe him? Well, here's a brief timeline of some of Murasaki and Genji's highlights over the centuries:

12th century

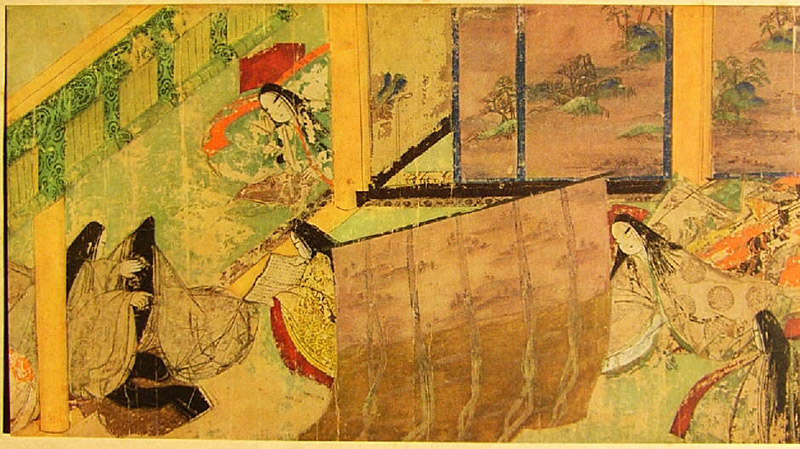

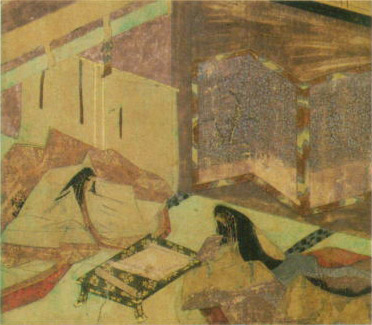

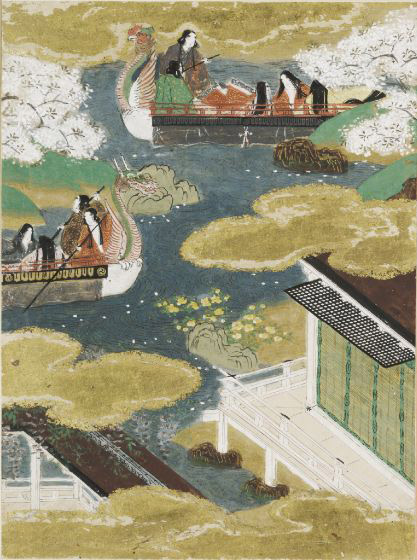

One hundred years after Murasaki's death, The Tale of Genji has basically become required reading for any literate Japanese person. Meanwhile, artists and calligraphers collaborate to create the picture scroll known as the Genji Monogatari Emaki, a very fancy picture book version of the tale that is now officially recognized as a National Treasure of Japan. Four scrolls with 19 paintings and 20 sheets of calligraphy (about 15% percent of the original) still survive and are currently housed at the Gotoh Museum and the Tokugawa Art Museum.

13th century

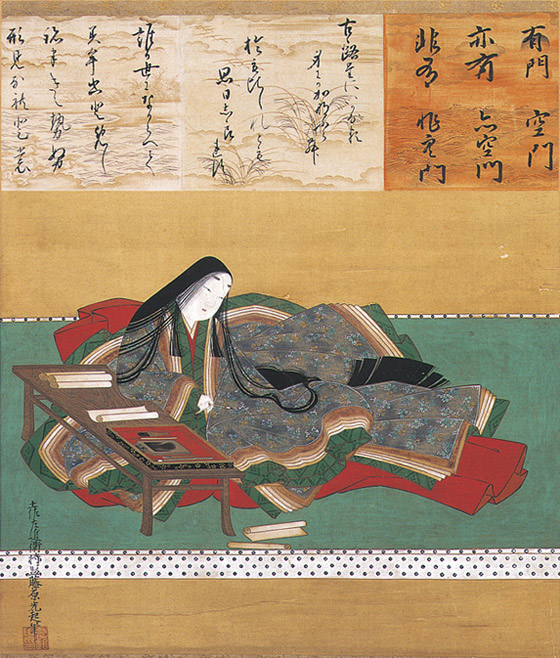

Another crew of artists and calligraphers get together—this time to commemorate Murasaki's own life by illustrating her diary in the Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Emaki scrolls.

Fujiwara no Teika also compiles the Hyakunin Isshu poetry collection (destined to become the star deck in competitive karuta), including this poem by Murasaki Shikibu:

めぐり 逢ひて 見しやそれとも わかぬ 間に 雲 隠れにし 夜半の 月かげ

I wandered forth this moonlight night,

And some one hurried by;

But who it was I could not see,—

Clouds driving o'er the sky

Obscured the moon on high.

(Translated by William N. Porter)

14th century

Murasaki's fictional creations start living and breathing in three-dimensional Noh plays. Aoi no Ue (or "The Lady Aoi") was the first of many plays to be based on characters and events from Genji. Aoi no Ue itself continued to have a life of its own, reinventing itself in the 20th century as a "modern Noh" play written by the infamous Yukio Mishima in 1954 and then a wacky avant-garde mash-up by Kara Juro in 1979. Apparently watching a female shaman exorcise the spirit of Lady Rokujo from the near-dead Lady Aoi never gets old.

16th century

Acclaimed artist Tosa Mitsunobu churns out 54 paintings revolving around Genji themes in a collection now known as the "Tale of Genji Album."

17th century

Confucian scholars declare that not only is Genji a fun way to waste time, if you read between the lines it's also a self-help manual that contains all you need to know to live like a good little Confucian. Prominent scholar Kumazawa Banzan prescribes a dose of Murasaki to everyone in Japan, especially the wimmins!

17th and 18th century

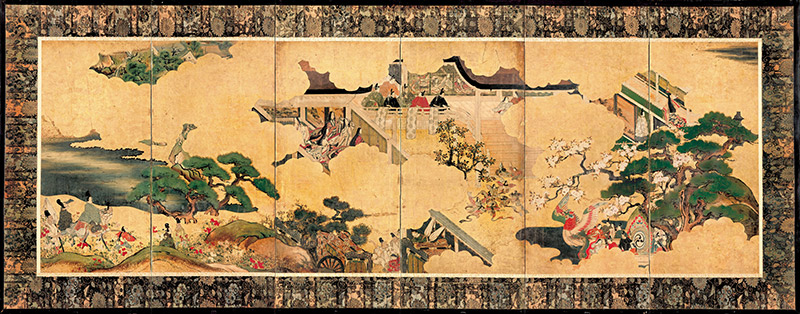

From byobu-e (screen paintings) and hanging scrolls to lacquer boxes, all things Genji become powerful status symbols, cultural caviar that everyone wants to display in the parlor.

18th and 19th century

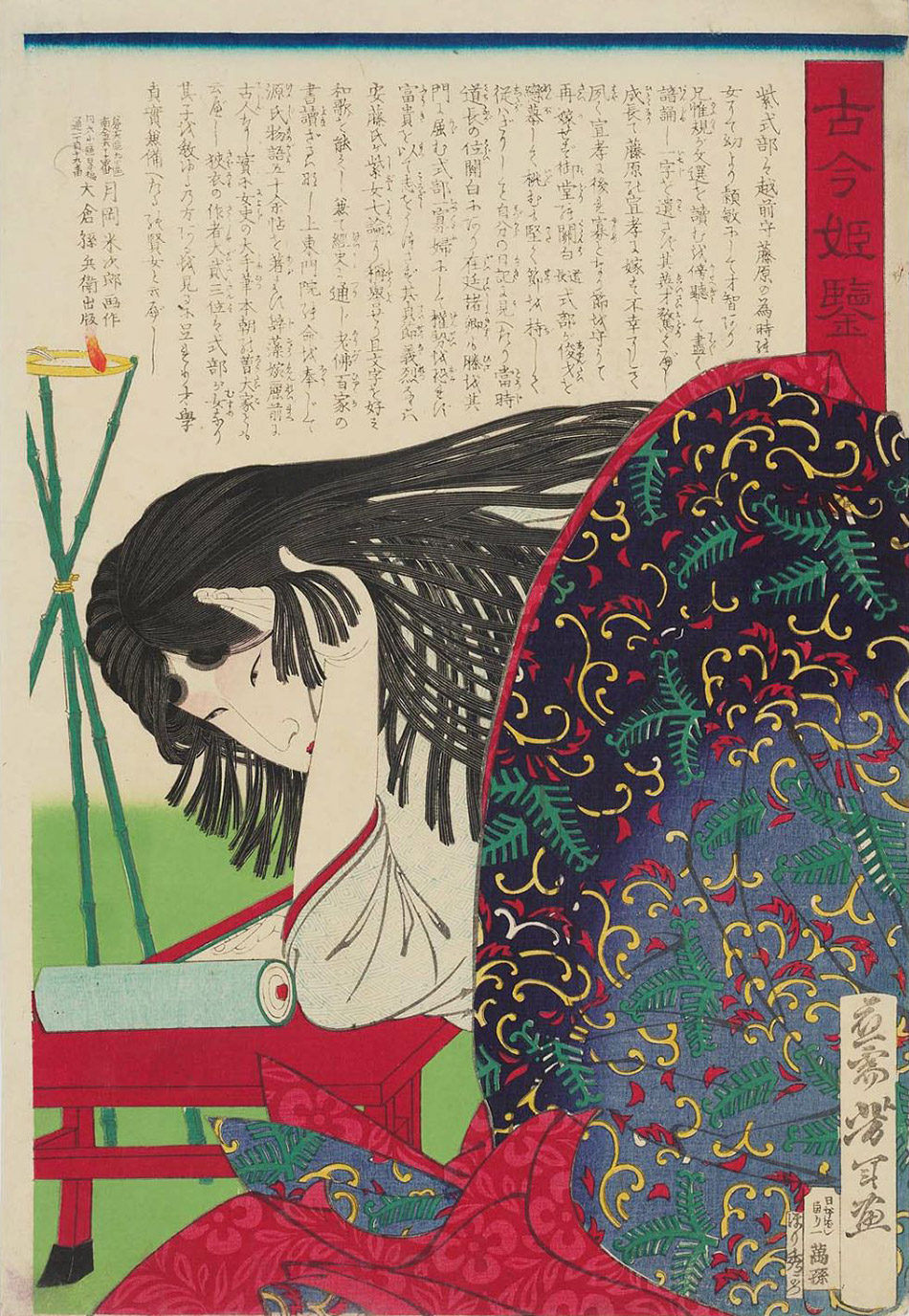

The less wealthy samurai and commoner classes don't want to be left out of the Genji craze, but can't afford all that fancy pants lacquering. But no matter! Just like cubic zirconia can make-do as fake diamond, inexpensive ukiyo-e woodblock prints stepped in to supply the Genji demand. Not everyone was kissing Genji's boots, though—Ryotei Tanehiko penned a parody called Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji that's been translated as "A Fraudulent Murasaki's Bumpkin Genji."

20th century to the present

The rest of the world finally discovers Murasaki Shikibu, and with that discovery comes a flood of translations into dozens of languages (including English).

Genji and friends find themselves suddenly on the silver screen (including the 1951 Tale of Genji, Sennen no Koi: Hikaru Genji, and Genji Monogatari: Sennen no Nazo), on living room television sets (in NHK dramas and anime like Genji Monogatari Sennikki), and in comic book panels (at least 5 manga versions, including the widely popular Asakiyumemishi and Miyako Maki's Shogakukan Manga Award-winning adaptation).

In 1991, the Murasaki Shikibu Prize for Literature is established, and is granted annually to one lucky female author who then receives a bronze statuette of Murasaki along with 2 million yen (approximately $20,000).

In 2008, Japan celebrates the 1000th anniversary of Genji with a year-long string of events and exhibits in Kyoto. And in Japan, of course, you're not really famous until there's a robot version of you. So the festivities included the unveiling of a mini-Murasaki-bot capable of reciting her namesake's poetry and fiction, making her the most ridiculously advanced audio book ever.

Over the last century it's become harder and harder for Japanese citizens to escape Murasaki Shikibu's clutches. Look up and there she is in the sky—Genji is the official name of a crater on near-earth asteroid 433 Eros, where all the geographical features are named after famous lovers. Look down and there she is on the ground—the flowering "Purple Gromwell" is called murasaki in Japanese in honor of the author. Retreat into the nearest building to escape from her gaze and there she is staring at you from your wallet—the 2000 yen note commemorates Murasaki and her novel. She's a popular lady, to say the least.

Where to Meet Murasaki Shikibu

In addition to all the Murasaki media mentioned above, there are some permanent pilgrimage sites in place that you can visit.

Ishiyama-dera at Lake Biwa

Legend has it that Murasaki was first inspired to write Genji while on a retreat at this Shingon Buddhist temple in 1004. While moon-gazing on an August night, inspirational lightning struck and she busted out a chapter on the spot. Regardless of this story's relation to fact, the temple has embraced the legend. There's a statue of Murasaki and a moon-viewing platform on the grounds, as well as a "Genji room" in the temple complex, complete with a life-size replica of Murasaki at her desk.

Murasaki Shikibu Park in Echizen

Echizen is where Murasaki traveled to and lived with her father upon his government appointment to the region. The park here is modeled after Heian-style shinden garden landscaping with a golden statue of Murasaki incorporated into the design. And the rest area serves free tea!

Rozanji Temple in Kyoto

This site was once Murasaki's home, the mansion where she was born and raised. Unfortunately the residence was destroyed by fire long ago, and the temple that now occupies the grounds also had to be rebuilt over the centuries. A single roof tile from the original mansion remains. Attached to the site is the "Genji-niwa" Zen garden.

Tale of Genji Museum in Uji

Opened in 1998, this unique museum features full-scale models, images, and exhibitions of Murasaki's life and the world of Genji, along with a library devoted to Genji-related books and documents.

Your local library

Alright, so now that you've heard all about it, are you ready to tackle the tale yourself? Reading Murasaki's writing is one of the best ways to experience her legacy first-hand. Students in Japan slog through selections of the linguistically archaic original Genji monogatari in class, but unless you've got a masochistic hankering to tax the limits of your classical Japanese knowledge, there are much less painful routes to take. After all, Murasaki's vocabulary and grammar was already obsolete just one hundred years after she wrote with it—language evolves pretty damn quickly. Most educated Japanese people couldn't hope to get through the original without a heavily annotated and/or illustrated version, so don't feel too bad about yourself if you can't either. You know that "summer reading" you've been meaning to get around to? Well, here it is!

If you consider yourself to be an advanced Japanese speaker/reader, you might want to crack open one of three modern Japanese translations of Genji. Akiko Yosano, Tanazaki Junichiro, and Enchi Fumiko are all well-regarded authors who went toe-to-toe with Murasaki in order to make her work more accessible to the 21st century Japanese speaker.

But if you're not quite ready for a full-fledged Japanese version, you won't be wasting your time with one of the three full English translations. (To help you choose, I've excerpted the same passage from each translation for ready comparison.)

Arthur Waley's 1935 Translation.

This one's a very free translation and omits a few chapters. It's also the one that first introduced the wonders of Murasaki to the English-speaking world. For 21st century readers, it's very obviously written in the early 20th century, which can be a good thing or a bad thing depending on your tastes.

Excerpt of the first paragraph of chapter two:

Genji the Shining One…He knew that the bearer of such a name could not escape much scrutiny and jealous censure and that his lightest dallyings would be proclaimed to posterity. Fearing then lest he should appear to after ages as a mere good-for-nothing and trifler, and knowing that (so accursed is the blabbing of gossips' tongues) his most secret acts might come to light, he was obliged always to act with great prudence and to preserve at least the outward appearance of respectability. Thus nothing really romantic ever happened to him and Katano no Shosho would have scoffed at his story.

(P.S. Katano no Shosho was famous for his romantic escapades.)

Edward Seidensticker's 1976 Translation.

This one was an attempt to more faithfully translate the original while still maintaining its general readability. (Disclaimer: this is my personal favorite)

Excerpt of the first paragraph of chapter two:

'The shining Genji' : it was almost too grand a name. Yet he did not escape criticism for numerous little adventures. It seemed indeed that his indiscre- tions might give him a name for frivolity, and he did what he could to hide them. But his most secret affairs (such is the malicious work of the gossips) became common talk. If, on the other hand, he were to go through life concerned only for his name and avoid all these interesting and amusing little affairs, then he would be laughed to shame by the likes of the lieutenant of Katano.

Royall Tyler's 2001 Translation.

This one made a very conscious attempt to mimic the style and conventions of the original, regardless of their intelligibility to the average American reader. To make up for this possible confusion, there's a bunch of explanatory footnotes! Its considered the closest to the original so far published in English.

Excerpt of the first paragraph of chapter two:

Shining Genji: the name was imposing, but not so its bearer's many deplorable lapses; and considering how quiet he kept his wanton ways, lest in reaching the ears of posterity they they earn him unwelcome fame, whoever broadcast his secrets to all the world was a terrible gossip. At any rate, opinion mattered to him, and he put on such a show of seriousness that he started not one racy rumor. The Katano Lieutenant would have laughed at him!

But don't forget about Murasaki's diary and poetry! Richard Bowring's 1982 translation titled Murasaki Shikibu: Her Diary and Poetry Memoirs brings the master's personal life to light. And then there's Liza Dalby's historical novel The Tale of Murasaki, weaving Murasaki's poetry and diary tidbits with an imaginative reconstruction of her life in Heian society.

What's So Great About Her?

Yeah, yeah, so this lady wrote a book about a playboy that a lot of people like. What's so great about that? Well, as you might have guessed by now, over the centuries Murasaki Shikibu became much more than an author—she became a cultural icon for the Japanese language itself, much like Shakespeare has for English (pushing the limits of the expressive power of English, adding hundreds of words and expressions to the language, providing tropes and quotes that gained lives of their own, etc.).

Murasaki Shikibu was instrumental in developing Japanese as a written language distinct from Chinese, transforming the spoken vernacular into a written one. In addition to strongly influencing later generations of Japanese writers who looked to her writing for stylistic and linguistic guidance, her works had a permanent impact on Japanese aesthetics within the culture at large.

Not that she did it alone—in fact, Murasaki was one of the many hyper-talented Heian court women who wrote some of the earliest and best literature of the Japanese canon, making her merely representative of Japan's long tradition of powerful female writers. Individually and collectively, their badass achievements transcended gender. With nothing more than an inkstone and some paper, they set the blueprint for a language currently spoken by 120 million people as well as all of us struggling to join those ranks.

Essentially, Murasaki Shikibu was such a badass that 1000 years after her death, here we are still talking about her. Samurai swords rust. Emperors come and go. But Genji is forever.