Thirty years ago a little book showed up that helped to educate the masses about Japanese women through a unique approach. It wasn't a work of fiction or a sociological study, but a list of words used for and by women in Japan that was able to shed some light on their place in Japanese society. It was bold, it was fresh, and its short essay entries made for a delightfully insightful read.

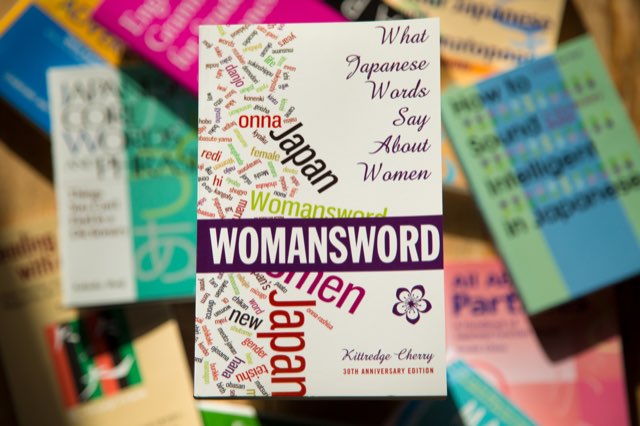

Womansword was published in 1987. At the time, it drew information from a huge well of the newest social studies, research, and one-on-one interviews with Japanese women. Now, all these years later, Womansword has just published a new 30th anniversary edition, and it remains one of, if not the best, English language resources for learning about the women of Japan through the language they use. Through the buzzwords explored in this book, readers are able to see exactly what the subtitle suggests: What Japanese Words Say About Women.

I'm not going to lie, a lot of the things you'll learn in this book are upsetting. Some of them will be cute or funny, but a good majority expose the uneven power distribution that exists in many modern societies. It also doesn't shy away from "difficult" topics: menstruation, prostitution, affairs, LGBT issues, miscarriage, double standards – it covers them all, without bias.

It may be tempting to try to read through the entire book in one sitting since it seems so short; it's hardly a few hundred pages. But the entries can be rather dense, making breaks and contemplation pretty necessary. Instead, I would recommend taking a few weeks to read it through, and then come back to it from time to time when you come across its contents in the real world.

About the Author

Before we go into specific entries you can find in Womansword, let's talk a bit about the author, Kittredge Cherry. When she traveled to Japan to write this book, she had no idea how much different her life would end up after she returned. I don't want to spoil everything, but she went from being a journalist for a Japanese magazine to discovering she was a lesbian. She also became a member of the Christian faith and eventually started the site Jesus in Love to promote LGTBQ+ friendly religious resources, and continued to write to promote her beliefs. These are some drastic changes.

Fast forward 30 years and she discovered that her book was still one of the only resources available to learn about the language relating to women in Japan. With Kodansha International (her original publisher) out of business, it became harder than ever to purchase the older editions. But she continued to see the world through what she had learned writing Womansword: that the words we use reveal how society feels. And when she was given the opportunity to re-release and expand upon the book, she was happy to meet the challenge.

Her writing and personality shine throughout this book. Her prose flows and sounds contemporary even 30 years later. She also made her own associations between Japanese and American cultures that help bridge the gap between some lesser known elements of Japanese culture.

Updated Content

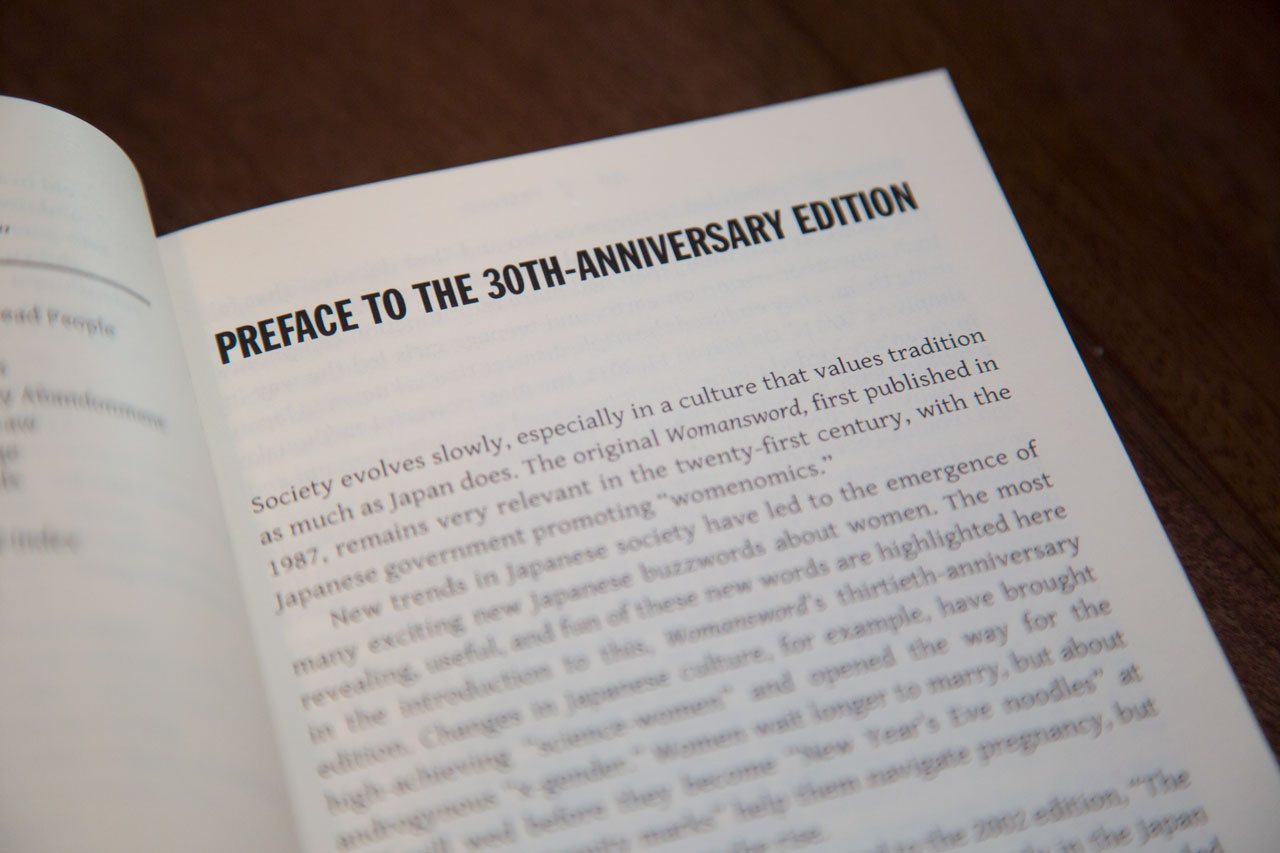

I found myself going back and re-reading the preface once I was finished with the rest of the book.

While the majority of the book is untouched, there is a new 30th anniversary preface written by Cherry that covers newer words that have come about since the mid-1980s. She follows the same structure the rest of the book follows: Female Identity, Girlhood, Married Life, Motherhood, Work, Sexuality, and Aging. However, there are no specific entries, like those that are found in the main content of the book. This information is the most relevant to the present day - some of it expanding upon older entries, and some completely new. This is one preface you should not skip. Here are just a few things you'll learn from the new preface:

- Japanese women are now moving toward a preference for daughters, rather than sons.

- Crossdressing and cosplay have become increasingly popular with both genders, leading to the bending of traditional gender roles.

- Women continue to have less children while the population of Japan is living longer and longer.

- Gay women are pushing for marriage equality and having ceremonies in places like Tokyo DisneySea.

- Womenomics is a very common term in politics thanks to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his push for women in the workforce.

I found myself going back and re-reading the preface once I was finished with the rest of the book. Partly because of my bad memory, and partly because some of the preface information was an extension of the original content. You may want to save it for last so that you have more context.

Formatting

Womansword is divided into seven chapters:

- Female Identity: "In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun"

- Girlhood to Wedding: "Christmas Cake Sweepstakes"

- Married Life: "Hey Mrs. Interior"

- Motherhood: "Honor That Bag"

- Work Outside the Home: "Office Flowers Bloom"

- Sexuality: "Pillow Talk"

- Aging: "Nice Middies Do"

Each chapter contains a dozen or so Japanese words. Entries are labeled in romaji, the English translation, and the original Japanese (in that order). Then there is a one to two page description going over the word's origin, history, social implications, and relevance today (meaning 1987's today, not 201X today). Other Japanese words that are referenced are written in romaji only, but with context it is usually easy to determine which words or kanji Cherry is referring to.

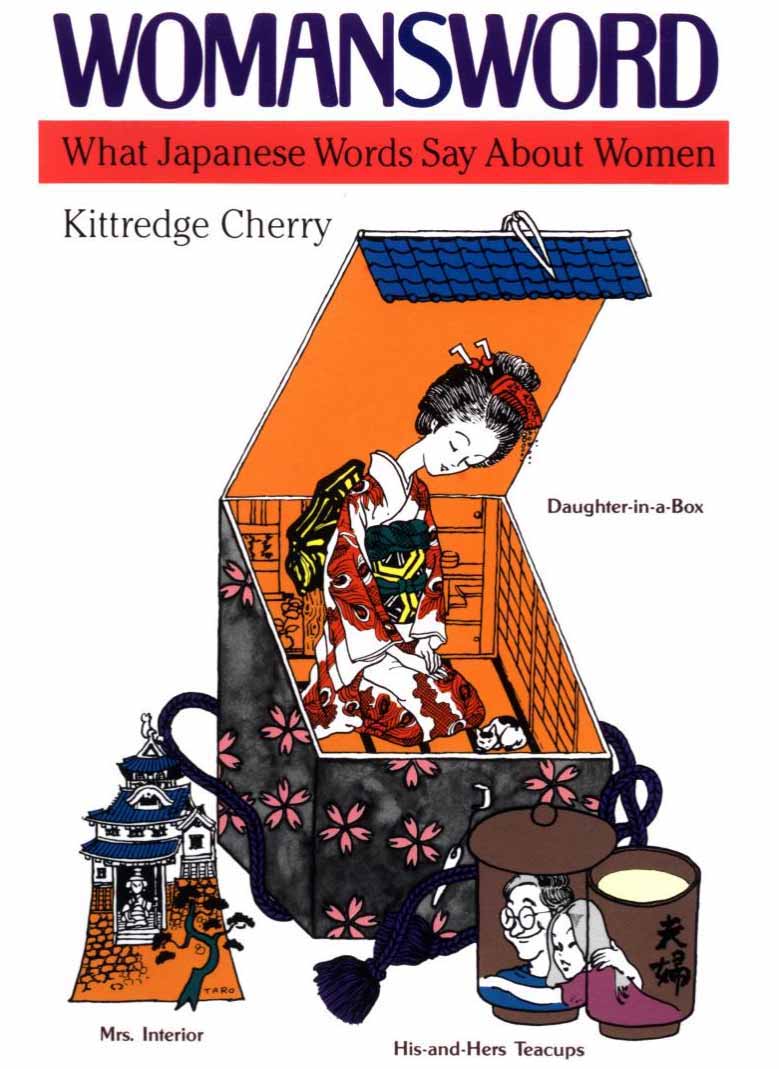

The cover is very different from previous editions, one of which illustrated a few stand-out entries including a Daughter-in-a-Box, Mrs. Interior, and His-and-Hers Teacups.

Instead, the 30th anniversary edition is more in line with other current Japanese textbook trends: White background, multiple English fonts, and a few colors. While this may not be indicative of the final print edition, it seems to be the same quality as other informational Japanese books like Jazz Up Your Japanese and How to Sound Intelligent in Japanese.

Some people love this style, some hate it, but it is a nice small size, easy for throwing in a bag. There is also a kindle edition available, which is great for people who don't want to deal with a paperback book.

In the back of the book there is a Japanese word index, which included the romaji and kanji words, as well as a subject index. This is especially helpful if you read the book in a short amount of time and want to come back to it later when you come across something you remember reading. The book is organized by chapter and alphabetical English order, so it can be difficult finding exactly what you're looking for, if it was something the author referenced to, rather than a word with a dedicated page.

Content

The woman kanji is used to make up a ton of other kanji. Many of them have negative, even offensive, meanings.

Womansword covers a wide variety of words sorted into seven different chapters. Reading through these words you'll learn about kanji, Japanese history, sexuality and gender dynamics, politics, holidays, and even some choice curse words.

There's nothing new to the original content of the book, so if you've read it before, you aren't going to be met with some astronomical revelation in these pages. Luckily for new readers, there is a ton of great stuff packed in these pages. Each section starts with a specific word or phrase. Here's a basic example:

onna Women 女 : This section delves into the shape and meaning behind the kanji for women 女. The woman kanji is used to make up a ton of other kanji. Many of them have negative, even offensive, meanings. And yet the kanji for man 男 is only used in a few, basic kanji.

A female and an eyebrow means flattery (kobi), while female and disease comprise a verb (sonemu) meaning to be jealous. A woman between two men means to tease (naburu); this is used in a compound with "murder" to say "death by torture" (naburu-goroshi). The onna symbol thrice repeated (kashimashii) means noisy or evil. A woman and a hand—that is, a seized woman—means a servant (do). A heart written below this character for servant makes the verb for becoming angry (okoru)." p. 48

She goes on to talk about more combinations that are less negative, and more telling of women's place in society: good + female = daughter; woman + take = wed; woman under a roof = content; and so on.

Without going into too much detail, here is a sampling (some highlights, if you will) of what you can learn in just a dozen or so pages of Womansword:

-

You know those cute kokeshi dolls you see everywhere? There are theories that the name doesn't really mean "little poppies" (小芥子), but instead "child erasure" (子消し). You see, in the old days, some poor Japanese people couldn't afford to have girls instead of boys. Girls cost more money, they would leave the family when they married, and usually couldn't carry on the family name. So they would commit infanticide. The dolls may have represented the little girls they "erased" (ie. killed).

-

Until 1984, the child of a Japanese man and a foreign wife was considered Japanese, but the child of a Japanese wife and a foreign man was not.

-

The Mamagon, or the Mama-saurus, is a mom who is super vicious. They push their kids to study hard and go to cram school. And they get blamed for everything wrong with their kids because it's the mom's responsibility to handle their education and not the father's. Which means anytime anything goes wrong it must be their fault. Low test scores = bad mama. This creates an image of loud, pushy moms that will do anything to make their kid succeed.

-

An umazume (stone woman or no-life woman) was a term used for women who couldn't bear children. Men don't have a word similar to this because everyone assumed that it was the woman's fault if she couldn't get pregnant. Oh, and there's a special place in hell for women who can't get pregnant too, as if being barren wasn't bad enough.

-

"Turkish Bath Girls" were basically prostitutes who worked in brothels disguised as bathhouses. But they were forced to change their names in the 1980s when a Turkish diplomat found out about them and wasn't very happy with his country being associated with sexy times. Now they're called "Soap Ladies" ソープレディ and they work in "Soapland" ソープランド invoking the image of a woman washing someone down with soap bubbles and um… other things.

-

The Japanese language didn't have a word for "dating" until pretty late in history. Because of that, they had to take it from English, which is why it's デートをする, which is literally "to do a date." Everything used to be arranged by the fathers, so all the old words have to do with the fathers or marriage, which is how we ended up with a loanword instead.

- Older women who spent their entire lives taking care of the home and hardly ever saw their husbands due to their heavy work hours have their worlds flipped when their husbands retire and spend all their time at home. Usually these men have nothing to do and so they sit around bored, bothering their wives all day. They become giant garbage 粗大ゴミ– sitting around as useless as a big, broken refrigerator. Usually sodai gomi is used for broken appliances that you can't just throw out with the rest of the trash. It also implies the trash is bulky and in the way. Sorry grampa.

This hardly even scratches the surface of what the book offers, but hopefully these excerpts help peak your interest.

Outdated and Missing Content

One thing you can't forget when reading through the entries in Womansword is this: it is a 30th anniversary edition. This is not a completely new book with tons of new research and content. If you have one of the older versions (like the 2002 edition), the only new content you're going to get is in the new preface. That's it. All of the data included in entries cuts off at 1986. Many entries are on words that are "slowly being phased out" or "no longer seeing much use" ~ but those "old" words were already old 30 years ago! It is very important that you keep that in mind as you read.

Many times I found myself involved in the history of a word, the social implications, and then I got to a study from 1983 saying something along the lines of, "but things are looking up!" and I would get frustrated. Well, what happened?

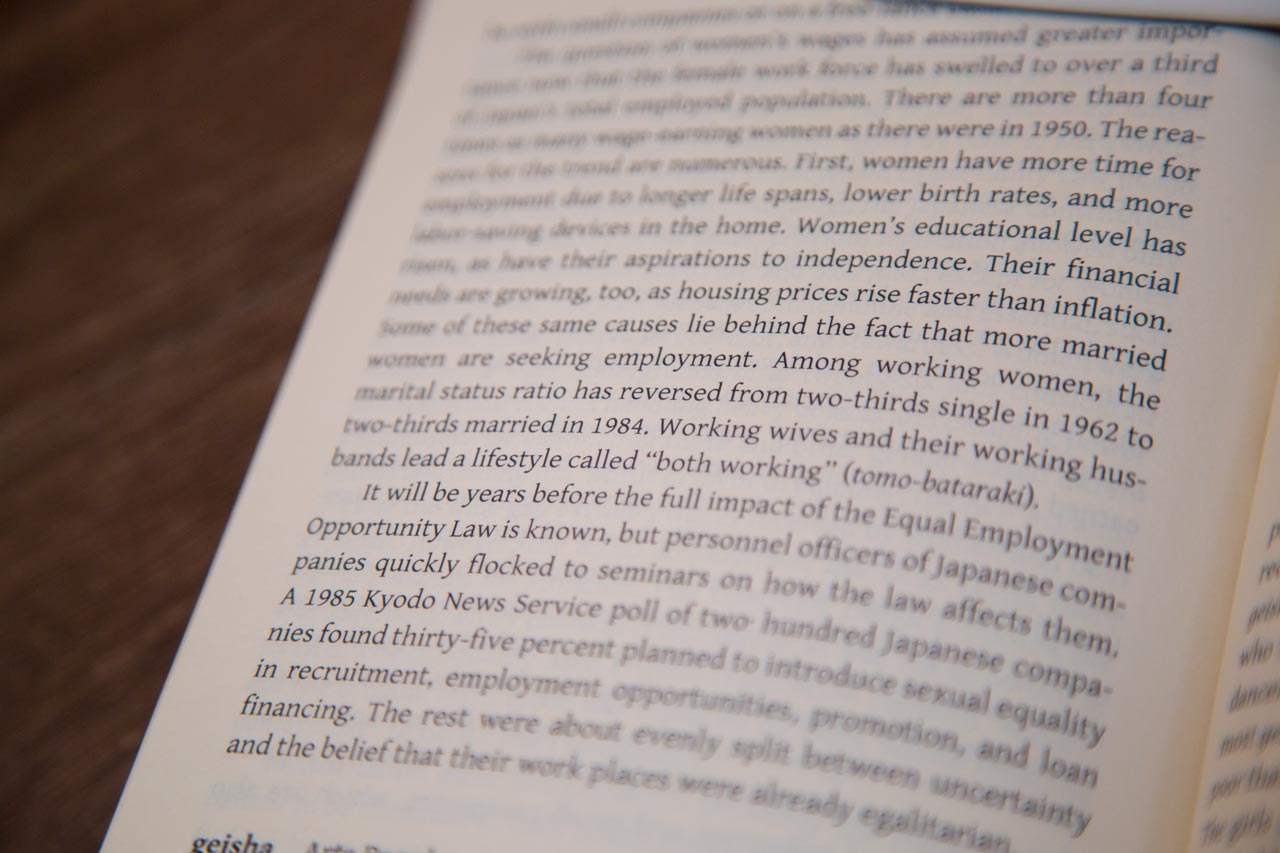

For a more concrete example: the section on the Equal Employment Opportunity Law, or 男女雇用機会均等法, says, "It will be years before the full impact of the [law] is known…"1. This is a pretty annoying break since it has been far more than a few years since the law's introduction.

One of the biggest problems with this are the statistics. How many women hold seats in office? How many women go on to higher education? How many women get divorced? Many statistics like this are in the book, and if you're using this as a source, you have to remember that this information is outdated. You have to look up current facts from reputable, contemporary sources before assuming they've stayed the same. So if you're hoping for a truly contemporary study of what Japanese words say about women, this isn't the place. If you're looking for historical context and don't mind doing your own research, you probably won't mind as much.

If you're using this as a source, you have to remember that this information is outdated.

Even without the latest information, the author herself says in the new preface that she had trouble researching for the newest edition. When she would look up a topic, she'd find the same resources she used decades ago. There is a real lack of research being done on this subject and one person can't do it all. This book still offers insight you can't find anywhere else.

This new version, though not as updated as many of us may like, does make the book more easily available. Finding old versions, even on Amazon, has been difficult.

Another thing to be aware of is something Cherry openly admits: many of the connections and assertions are hers alone. While she did consult with many people, some may not agree with everything she has written. But as with all things, it's important to take everything with a grain of salt. If you don't agree with a connection an author makes, find your own, better answer.

Womansword Final Verdict

Womansword is an insightful book that anyone interested in the Japanese language, the social climate of Japan, and even just the history of women will enjoy. It can help you make connections from your current knowledge, open your mind to new meanings, and expand your knowledge of the language and the hidden nuances behind the words you hear every day. Even for native Japanese people, there's plenty to learn from this book (as proven by its previous success in Japan).

While the book has become "dated," the terms, research, and connections you can find within it are still important to the study of women and language in Japan. Just make sure you understand that not everything is going to be accurate today, before spending your money.

I strongly suggest that anyone taking a course on women in Japan or Japanese history, use this to look for paper topics. It's full of ideas and possibilities that can turn into a fantastic research project. And even for self learners, it may lead to some unique conversations among your Japanese friends and tutors. And there may be a silver lining to the age of this book: it's a fantastic starting-off point, leaving plenty of room to promote individual research and growth.

Kristen’s Review

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. Reading about linguistic and cultural etymology is one of my favorite hobbies, so I was thrilled when this new edition of Womansword was released. Even though some of it wasn’t as well updated as I’d hoped, the content really does hold up well, even after thirty years. I’d definitely recommend this to anyone who’s interested in the history of women in Japan or just the culture behind the Japanese language, in general.

-

p. 124 ↩