Jay Rubin is one of the biggest names when it comes to the Japanese translation scene. He is one of Murakami Haruki's main English translators (Norwegian Wood, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, 1Q84, etc.) and a former Japanese professor at Harvard University. If there is anyone I wish I could get Japanese or translation advice from, it's him. He is enjoying his retirement, so I can't really go bother him, but I did the next best thing. I picked up his only book on the Japanese language, a little paperback called Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Don't Tell You. Needless to say, I was more than ready to learn from one of the greats. And let me just say, I was not disappointed. Reading through this book made me wish there was some way, any way, I could have taken some of his courses.

One disclaimer: this is not a typical textbook. It is made up of two parts titled "Who's on First?" and "Out in Left Field," including a number of essays about different aspects and quirks of the Japanese language. It does not have vocabulary, practice pages, quizzes, or charts. But that does not make it any less helpful than a standard textbook, as long as you have sunk a solid few years into Japanese before you give it a try.

Why Didn't They Tell Me Before?

The real advantage to reading this is that you can begin to unlearn all of the simplified and strange shortcuts you were taught when you started learning Japanese. As a student of the first version of The Genki Series, it took me a long time to realize some of the things I thought were simple were just the opposite. But for the sake of not driving away new learners to the language, these new things were made to seem like they were one-sided, easy concepts. This book covers a number of these, like the real difference between wa and ga, how to properly understand what adding hodo actually makes your sentence mean, what you are implying when you use directionals, the fact that there is no such thing as a subject-less sentence, and how to stop thinking Japanese is a "vague" language just because so many people keep telling you it is. (It's not, seriously. Stop saying that.)

I can't help but feel that my explanations aren't doing enough justice, so I'll give you a taste of one of my "Oh wow, I get it now," moments from the book.

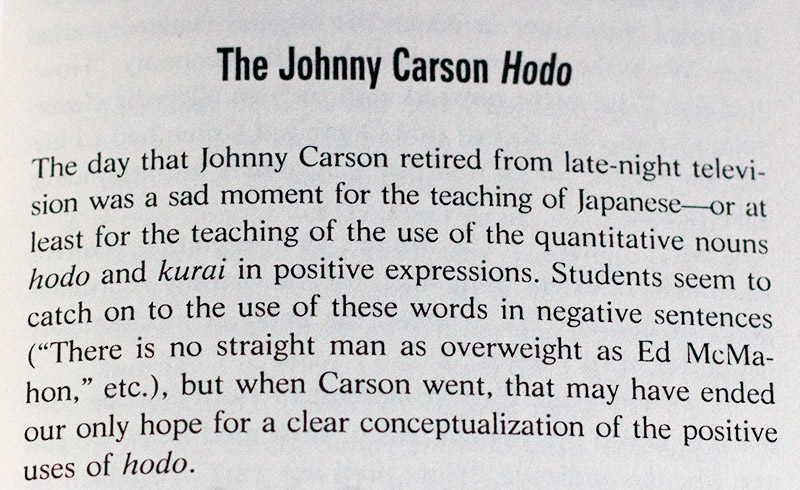

He has an essay explaining the use of hodo (ほど) using an example from the late Johnny Carson. For all the younglings out there, Carson was the host of The Tonight Show (with Johnny Carson, of course). He used to have this thing, which Rubin explains in the essay, where he would say something like, "It's cold today," and the audience would respond, "How cold is it?" Or "How x is it?" depending on what the topic of the joke was. And he would respond with "It is so cold that…" and finish with something funny and witty. Rubin goes on to explain that it is this exchange that is being expressed when we see a sentence using hodo with the following examples:

- [Yasumu hima ga nai hodo] hatarakimasu. He works so much. How much does he work? He works so much that he has no time to rest.

- Kono shigoto wa [kodomo de mo dekiru hodo] yasashii desu. This job is easy. How easy is it? It's so easy even a child can do it.

There are four more examples, but at number 2 it just clicked. Here's the rest, for those interested:

- Yori nemuru koto ga dekinai hodo] shinpai shimashita. I worried. How much did I worry? I worried _so_much I couldn't sleep at night.

- [Ōbā mo iranai hodo] atatakai desu. It's warm. How warm is it? It's so warm you don't need an overcoat.

- [Nakitai hodo] komatta. I was upset. How upset was I? I was so upset I wanted to cry.

- Ano hito wa [tsukaikirenai hodo] kane ga aru. He has money. How much money does he have? He has so much money that he can't possibly spend it all.

He doesn't stop there. Elaboration feels like the biggest strength of this book, besides the quirks and popular (though a bid dated) culture references. He then goes on to explain how hodo works when used with negatives:

All About Particles (Power Japanese, p. 66) provides examples of >both kinds of usage. For the easy negative type:

Kotoshi wa kyonen hodo samuku nai desu. / "This year is not >as cold as last year."

For the harder positive type we find: Kyō wa benkyō ga dekinai hodo tsukareta. / "Today I'm so >tired that I can't study."

Once I was finished with the chapter I felt like I understood hodo better than I ever had in a classroom. Having multiple explanations laid out in English, explained in his style, makes you understand the feeling and purpose held in that little piece of grammar. Maybe I've just had mediocre professors in the past, but this felt like the way you are supposed to be taught.

It Can't Be That Great

No, it really is. My only complaint? It's all in romaji! I know I have complained about this before, but it really gets on my nerves. If you were in Japanese class, your professor would not give you examples in romaji. Life does not give you examples in romaji. Oh well… I guess people have their own preferences. So if you don't mind, or maybe even prefer this, there really is no downside. And to be honest, it does get easier to read the more you get into it. That may be because it fits with his writing and example style so well.

Making Sense of Japanese - Verdict

There are these little moments throughout each essay where (hopefully) the point or the nuance he is trying to explain suddenly clicks. All those instances of x particle or x piece of grammar are so much clearer than they ever were. You can't breeze your way through this book though. It may be small, but you really need to be reading slowly and thinking clearly to understand what he is saying. It is certainly not for beginners, but anyone past the lovely intermediate roadblock in their Japanese studies can easily get something out of it. I would highly recommend this book to people interested in translating Japanese to English, and are looking for a starting point in the type of theories and language breakdown that is required of translators. It is entertaining, though a bit high brow, and full of explanations and elaborations on things you thought you already learned. And if you are one of the many people confusing は and が, look no further.

Let me leave you with my favorite quote from the book, and what he has to say about Kanji.

Kanji are tough. Kanji are challenging. Kanji are mysterious and fun and maddening. Kanji comprise one of the greatest stumbling blocks faced by Westerners who want to become literate in Japanese. But kanji have nothing to do with grammar or sentence structure or thought patterns or the Japanese world view, and they are certainly not the Japanese language. They are just part of the world's most clunky writing system, and a writing system cannot cause a language to be processed in a different part of the brain any more than it can force it to some other part of the body (excepting, of course, Lower Slobovian, which is processed in the left elbow).

To this, I can only add that banana skins provide one of the best surfaces for writing kanji if one is using a ballpoint pen. Since this book is intended to help with an understanding of the Japanese language, it will have nothing further to say about kanji.

Kristen’s Review

I’ve probably read through this book three different time in my years of Japanese studies, and I can honestly say it’s something all Japanese language learners should skim through at least once. If Jay Rubin has something to teach you about Japanese, you listen.