For those of us learning Japanese, there's a lot we have to do. From active studying like reading textbooks, to practicing skills like speaking, and trying to read and watch native material, the work needed to reach a high level of Japanese proficiency is vast. But regardless of your method of active studying, there are a lot of things you'll simply need to memorize. Specifically for Japanese study, learning new words is a big memorization project, but thankfully one that can be made easier. Through various spaced-repetition systems or SRS, a learner can take the guesswork out of when to review a specific term to make sure it sticks. There are a number of SRS programs, but I'd like to take a look at one that remains enduringly popular over the 15 years since its initial release: Anki.

With its expansive range of add-ons and shared user "decks," the ability to be synced across platforms, and its deep customizability, it's no wonder Anki has found a thriving and vocal group of enthusiasts, including a community of supportive Japanese learners. Still, with great power comes great responsibility, as Anki has a well-earned reputation for its Byzantine options, and all but requires serious configuration and additions to make the most out of it.

For years, I put off getting set up with Anki, as every time I tried, I soon became frustrated by its myriad options and at-times dogmatic users all extolling the "One True Method." Hopefully, for learners who are unfamiliar with Anki or just hesitant like I was, I can provide some of the details I wish I'd known earlier, talk a bit about the setup process, and show why it's so beloved in the Japanese learning community. Once you get off the ground with Anki, it can be a super powerful application, but you should know what you're getting into before you jump into the deep end.

- What Is Anki?

- Okay, So Why Use Anki?

- Anki Terminology

- Setting Up Your Own Anki Deck

- Studying with Anki

- The Bad

- Is Anki Worth the Hassle?

What Is Anki?

Anki is an open-source SRS app available on Windows, Mac, and Linux, as well as iOS and Android. It's free on every platform except iOS, where it costs $24.99 as a means of supporting the rest of the development.

At its core, Anki is a flashcard application. Users make digital flashcards with pieces of information arranged on the "front" and "back" sides of the cards — Japanese words and their English translations, for example. As you might imagine, these cards are then grouped into "decks" for you to review from, and you can even share your decks with other users, or download their decks to use for yourself.

Built-in SRS (Spaced Repetition System)

But rather than simply letting you review flashcards at your own pace, Anki has a built-in SRS algorithm, which automatically adjusts which cards it shows you and how long until it asks you to review them again, all while you're doing your reviews. In short, after you create a card and review it for the first time, you're asked to grade how well you were able to recall the information on the card. Based on your response, Anki's algorithm will adjust how long until it shows you that card again — if you tell it you remembered it well, it'll wait a little longer, and if you say you struggled to remember it, it'll show you that card sooner. The intent is to show you a card just before you forget the information you put on it, so that you can efficiently move it to your long-term memory rather than leaving it as something you're likely to forget. Because of how this process works and the effectiveness of it, SRS apps are very well suited to building a large vocabulary in a new language, though you can use them to memorize basically any set of data you want to.

SRS apps are very well suited to building a large vocabulary in a new language.

This is all well and good, but do you really need to use an SRS? You certainly don't have to, but doing so makes it a lot easier to reach a high level of Japanese proficiency. At some point as a second language learner, you'll need to build up your vocabulary. You don't want to be caught in a conversation and suddenly realize you don't know the Japanese word for "grapes" (true story!). Studies have shown SRS programs to be highly effective, so why not leverage that efficiency for your own goals? Really, it's no different from the textbook or classroom study you're already taking advantage of — think of all these methods simply as multipliers to your own natural acquisition ability.

Studies have shown SRS programs to be highly effective, so why not leverage that efficiency for your own goals?

But couldn't you just read a bunch and learn things naturally? Native speakers don't use an SRS, after all. Of course that's a valid point, but you should remember that native speakers have years and years of immersion experience you don't have. While you probably could just try and read a lot of books (maybe around 150 or so) and slowly build your vocabulary over time, that process is haphazard, and without a way to capture and practice those new words, you might end up forgetting them anyways.

It's cool to see my vocabulary grow in specific directions based on my interests or the media I'm interacting with at any specific time. For example, while playing Zelda in Japanese I picked up words like 研修 (kenshū, training), 剣 (ken, sword), 広場 (hiroba, town square), and 勇者 (yūsha, hero), but would've learned completely different words if I had instead read a romance novel. I can't tell you how many times I've been having a conversation in Japanese, only to realize I don't know some word that seems shockingly common, but that I simply never came across in native material before. Unfortunately, this is probably an inevitable situation, but makes it all the more important to make sure the words you're coming across do stick.

Okay, So Why Use Anki?

Alright, you've sold me, I'm ready to boost my vocabulary. But why should I use Anki, especially when I could use something I don't have to fuss around with?

Almost everything in Anki can be tweaked.

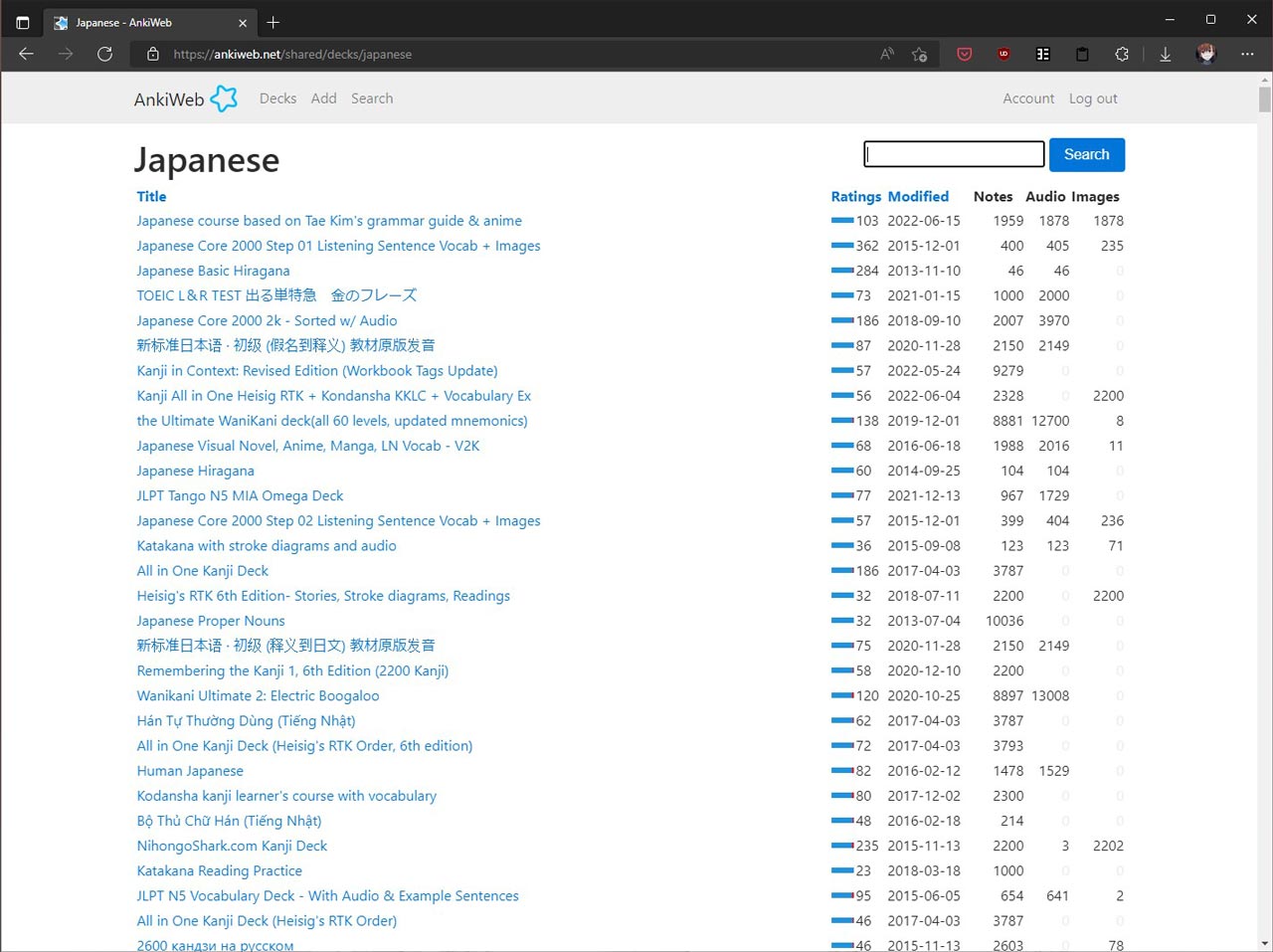

I felt the same way for years, and though I'm of course biased, the ease of getting started is one of the main reasons I feel WaniKani is a great option for learners at any level to start learning to read Japanese. But with any system that you don't make yourself, including the premade user decks on Anki, you're stuck learning words that might only be somewhat relevant to your interests or your Japanese level, and you're limited in the information that you're able to decide is important.

Additionally, almost everything in Anki can be tweaked, from the way cards look and the information they contain, to functionality (such as adding in an input field instead of the grading buttons), to the range of add-ons that shape the experience — even the algorithm itself can be modified based on your preferences or needs.

Making your own flashcards is also just a great study practice.

Making your own flashcards is also just a great study practice. Think about borrowing your friend's notebook before a big test, versus making your own notes during the class. When you're making your own deck, you can choose what words you're learning, where they come from, and what information you want to learn with them.

Making Your Own Flashcards

I think "input" has to be a pretty big part of your study process to get the most out of Anki.

Sounds great, right? Well, not so fast. Personally, I think Anki isn't quite for everyone. While you can jump right in with a premade user deck such as one of the popular Japanese "Core" decks (which usually contain somewhere between 2,000 and 6,000 of the most common words in Japanese by frequency), you'll get the most bang for your buck by making your own decks. There are a number of reasons for this. For one, it pairs rote memorization with language input (since you'll need to find the words you want to memorize from somewhere), and input is essential to reach a high level of proficiency. Then you also get the benefit of deciding what words are worth making a card of, the active thought process of which is useful. Finally and perhaps most importantly, through this process you'll know the cards you're making are relevant to your interests and ability, rather than just being pulled from a list.

But because of all this, I think "input" has to be a pretty big part of your study process to get the most out of Anki; that makes it more suited to intermediate learners rather than absolute beginners. Of course, I think it's great to start incorporating input as early as possible, and you can use Anki to help get yourself to the intermediate level — maybe you'll make a deck of the kana, for example.

Anki is not only something that takes time to set up, but also time to maintain.

Finally, you should know that Anki is not only something that takes time to set up, but also time to maintain. It's a program meant to grow and adapt with you as you learn more, and as your learning needs change. Language learning itself is a big commitment, and of course there's nothing preventing you from stopping using Anki whenever it doesn't suit you; but you should know what you're getting yourself into.

The Need for Speed!

But this customizability isn't the only reason to use Anki. One of my favorite parts of studying with Anki is just how fast it is. I mentioned this earlier, but by default Anki doesn't ask you to select the correct answer or type in a definition. Instead, you're only asked to grade yourself on how well you were able to recall a word. Because you don't have to type anything in, it's easy for you to take out your phone and flip through some flashcards while you wait for your coffee or something. Of course, this also means it's easy to cheat, something that would only hurt you down the road. But on the other hand, this makes reviews insanely fast.

Anki doesn't ask you to select the correct answer or type in a definition. This makes reviews insanely fast.

Before starting a review session, Anki will estimate how long it will take, based on the time you've spent before. I like to think I've got a good strategy for handling my WaniKani reviews, but my review sessions still take me an average of 30 to 45 minutes every morning; I can finish Anki in no more than 15 or 20.

Now that I've got everything set up, neither making new cards nor studying with them takes much time at all, leaving me plenty of room to do more stuff in Japanese — the primary reason I'm studying Japanese at all. I have more time to spend reading, which is the main way I study right now. Of course, reading is a lot more fun than looking at flashcards or "studying" in a traditional way anyways; it's a win-win!

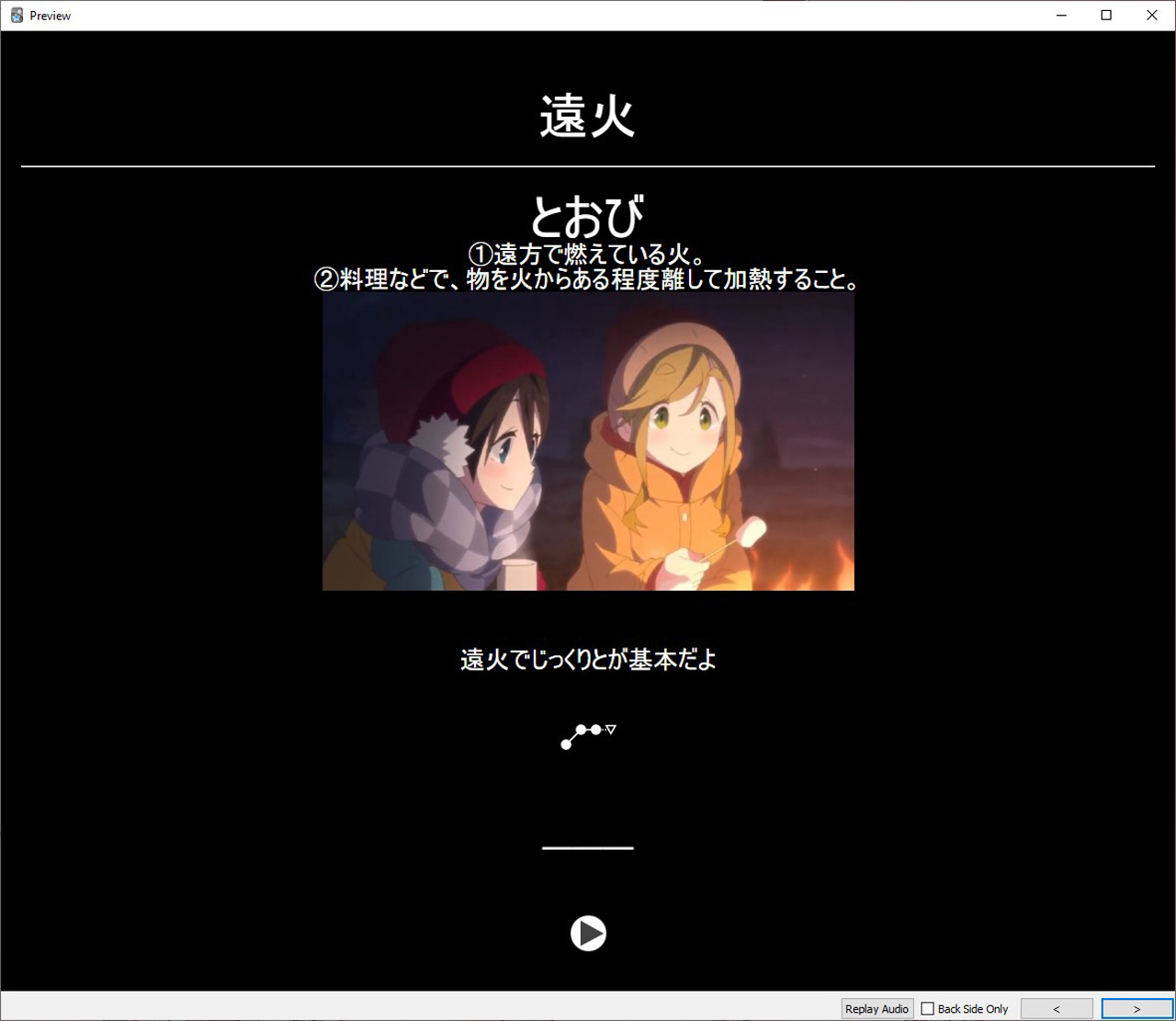

Integrations & Workflows

The other big reason to use Anki is all of the integrations it offers. Anki is notoriously dense to set up, a claim I think is true, but because of this there is a whole cottage industry of add-ons and integrations that make using Anki a breeze. Let's say you wanted to watch an anime like Yuru Camp and make flashcards out of all the words you don't know. This is easy with a support application like Migaku, which can do all the heavy lifting of making flashcards with the relevant info for you.

There is a whole cottage industry of add-ons and integrations that make using Anki a breeze.

For my money, the single best integration is with the pop-up dictionary browser extension Yomichan. Yomichan allows you to make a new flashcard with a single click of a button after using it to look up a word.

There's also a ton of incredible plugins for Anki, some of which can automatically pull audio for a word, resize images, generate furigana, add pitch-accent diagrams, and much more. No matter what type of cards you want to make, or from what source, you can bet there's a good add-on or support app to make it easy.

With that out of the way, let's talk a bit about how Anki works and some key concepts to understanding it.

Anki Terminology

Back when I was Anki-curious, I kept seeing the same refrain offered to Japanese learners hoping to get started with Anki: read the manual! Doing so dropped me into a massive and dense document, filled with terms like "ease" and "cloze." Thankfully, there are only a few pieces of information you'll need to get started, and even better, there are tons of guides on specifically customizing Anki's default options to suit learning Japanese vocabulary, such as the Animecards site or Refold's guide.

Let's look at some of the basic information you'll need to hit the ground running.

Cards

As I said before, Anki is basically the digital version of a deck of flashcards you might've used in school. But Anki, being digital, has a number of benefits, like the ability to nestle decks inside one another. By default, an Anki card contains some information you put on the "front" of a card, which prompts you to recall the rest of the information. Specifically for studying Japanese vocabulary, most learners make cards that present you with a word in Japanese, or a sentence that contains a word you don't know.

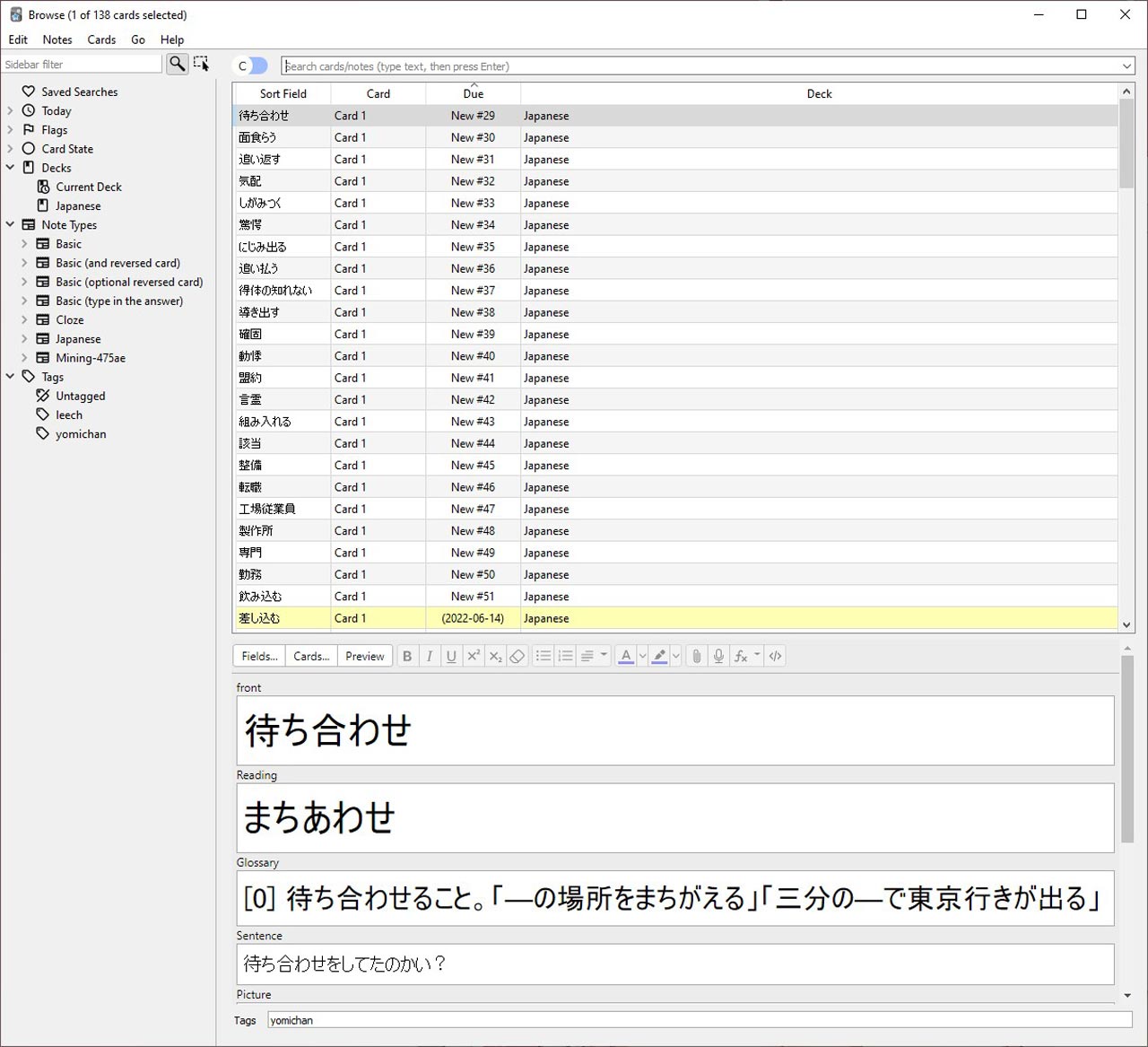

Then, after you think about it, you can press a button to see the "back" side of the card, where most people put the definition of the word in either Japanese or English, a sentence, maybe a definition of the sentence, audio of the word being read, etc. As you can see, these cards are quite flexible, and you can put what you think is useful on them. I would encourage putting a definition in simple Japanese, audio of the word being read, and a sentence showing the word in context (ideally the sentence where you found the word; pulling sentences with unknown words from native material like this is known as "sentence mining"), but don't feel like you have to spend 15 minutes making every single card. Anki is so popular and powerful because many of its add-ons and integrations make it quick and easy to create cards that have all the info you need — without having to fuss around too much.

Notes

Great, so we understand what a card is, but what exactly is a note? A note is just a collection of different pieces of information. Isn't that the same as a card? It's close, but not quite. Basically, a note allows you to group information in a more fluid way than simply collecting information rigidly into the front and back of a card.

For example, in the card above, we have at least 4 "fields," or pieces of information: the word itself, the definition of the word, a sentence, and an audio recording of the word being read. If you were limited to only cards, you'd have to group the definition, sentence, and audio together on one side, and the word itself on another, meaning you'd need to make a whole new card if you simply wanted a set of cards that gave you the audio and asked you to recall the written word. But because these items aren't grouped like this, you're given a lot more flexibility in making new cards, if you want to test from English-Japanese instead of Japanese-English, for example.

Decks

Finally, a deck is a collection of cards. Anki lets you put decks inside one another, so while it's technically possible to have a number of smaller decks of more specialized info, I wouldn't recommend it. One reason for this is that it can make things a bit too easy if you already know that the word you're looking at has to be an "animal name" for example, or that it came from Yotsubato! Instead, I would recommend adding all of your vocabulary cards, whether you decide to make them sentence or word based, into a single deck. That way, you're not giving yourself any context clues as to what you might be looking at. (It also makes reviewing even quicker, since you only have to select the one deck to start!)

Setting Up Your Own Anki Deck

Now that you know what Anki is and how it works, let me talk a bit about how I decided to set up my Anki deck. Deck setup is very personal, depending on your own needs and preferences, and as I've mentioned before, there are tons of different guides online with different suggestions on what's most efficient. I'm someone who doesn't want to spend a bunch of time messing around with settings, so I decided to set up my deck in-line with one of these guides. I'm sure there are people who would recommend something different, or wouldn't choose the same settings I have, but using a guide allowed me to hit the ground running, and so far I have no complaints with how the review system has worked.

Additionally, I decided to use this shared deck as the template for my cards, removing the need for me to get into the CSS (a programming language that tells websites how to look, and is also used by Anki) to adjust how the cards look or the information they contain.

Like I said earlier, my primary method of making new cards is with Yomichan. I use Yomichan with a couple of Japanese-Japanese dictionaries, and based on the card template, Yomichan will automatically add the sentence the word came from, the reading, a pitch-accent graph, the audio of the word, and more into a new card in my Japanese deck. There are also fields to add a picture for context or the audio of the sentence, if you're pulling material from a TV show for example.

For adding images and sentence audio, many recommend the free application ShareX for Windows. This lets you assign a keyboard shortcut to make a new screenshot or audio recording, which can be copied to your clipboard and then pasted directly into Anki.

Finally, I'm also using the AnkiConnect add-on, which is necessary to connect Yomichan and Anki together. I use the add-on called ImageResizer to — you guessed it — resize images, Japanese Support to generate furigana and much more to make studying Japanese quick and painless, and Yomichan Forvo Server to give Yomichan access to the Forvo pronunciation dictionary website to pull audio from if it doesn't have audio for a word already.

Studying with Anki

So now that you've got everything set up, what's studying with Anki actually like? As I've mentioned, you're simply asked to grade yourself on recall once you flip a card and reveal whatever information you've decided to test yourself on. Then, Anki shows you 4 buttons: Again, Hard, Good, and Easy. As many have noted, pressing either the "Hard" or "Easy" buttons not only tells Anki if you did well or poorly recalling the item, but it actually changes the interval between that review and whenever the next one will be from that point on. Basically, if you tell Anki a card was "Hard," not only will it show it to you sooner, but it will always show it to you sooner than it would have otherwise in the future, even if you start to learn it better over time.

Because of this, I only press the "Again" or "Good" buttons while I'm studying. This keeps the interval the same, but lets Anki decide how long to wait before it shows me the card again. If I'm learning a word for the first time, pressing "Again" will literally show the card to me again in the same session, whereas for a card I'm learning pretty well, pressing "Good" might delay how long until I see the card again for weeks or months.

I've added a range of cards, from books, anime, visual novels, and web articles, with a range of different fields used. Still, reviewing all of these together is a breeze.

The Bad

For the right type of learner, Anki is a super powerful application. That said, it's one with a ton of caveats and qualifications. To start, it looks and feels like an application from 2006. It's a gray window on a desktop, and while a few parts of the application have been updated over time, like the "deck options" page, it's a far cry from the elegant and streamlined apps we've come to expect in 2022. You have to manually press a "Sync" button to sync between platforms, for example.

Anki looks and feels like an application from 2006.

Like a lot of studying, what you'll get from Anki is what you'll put into it: from the quality of your cards, to making sure you don't cheat yourself, it's as powerful a tool as you make it. But Anki itself sure doesn't make it easy. Even deciding what type of cards you want to make is a difficult and dogmatic decision, let alone how you choose to set your intervals, ease, and modifiers. I highly recommend finding a guide you like online and sticking with it; you can always adjust things as you go. There's also a ton of helpful YouTube videos, including many specifically for Japanese language learners, that aim to illuminate some of Anki's darkest corners.

If you've spent any amount of time in any of the online Japanese language learning communities, you'll find scores of people who swear by Anki as an essential tool to achieving high Japanese proficiency. And I agree, it can be extremely helpful in building a vocabulary. But I think it's important to note the difficulty in getting Anki to a helpful place, as it definitely doesn't come that way out of the box. Instead, expect to spend at least a bit of time finding various guides, integrations, add-ons, and templates to get things just right; or even longer if you want to set things up by yourself from scratch.

It's important to note the difficulty in getting Anki to a helpful place, as it definitely doesn't come that way out of the box.

Even once that's all set up, it's important to keep Anki in perspective. At its most fundamental, it's best for building a vocabulary. Certainly, this is a huge and important part of language learning, but only a single component of it. Even if you decide to focus your cards on sentences to promote reading and context, you're still just learning new words. I tend to think the people who ask online, "I know 6k words, why can't I smoothly read __ yet?" have the wrong idea. Even in a perfectly optimal studying environment (whatever that might be), you'll need to study kana, grammar, phonetics, and more — especially if you want to reach a high level in all domains of Japanese, instead of just learning to read, for example. Of course, all these items should be cemented and improved upon by immersing yourself in native material, but you still need that foundation to start. Anki can help you get there, but not without some work.

Is Anki Worth the Hassle?

So, if it's a hassle, is it worth it? Well, if you're an intermediate Japanese learner, who's starting to engage with more native material and wondering, "What am I supposed to do with all these words I'm looking up?" Anki might be just what you need. There's a reason such a clunky, annoying application has endured and remained oddly beloved, even over 15 years since its release: and that's the power, flexibility, and customizability it offers, all for free.

But free as it may be, it still comes with a price: the annoyance of getting everything in its right place. With all the guides and support apps, it's never been easier to get Anki set up, but that doesn't mean it's easy. Despite the allure, I hesitated for years, rebuffed by the complex options and intimidating experience. But once I got everything set up, I was glad to finally understand what all the hype is about. Anki has already become a key part of the next step of my Japanese study journey, and a tool I expect to use for years to come.

Ian’s Review

As a Japanese learner, you’ll need some way to grow your vocabulary, and because of the expansive range of options and deep customizability, it might as well be Anki. The ability to make your own flashcards is extremely powerful, though getting started is more than a little frustrating. If you can make Anki’s workflows suit your needs, it’s a great way to memorize a ton of words, but doing so isn’t as user-friendly as we’ve come to expect from applications in 2022.