If you were just beginning to learn about Japan, there might be some concepts and references in the conversation of old Japan hands that go right over your head.

I brought some omiyage from my trip to the onsen to the office, and after work we went out to an izakaya and my boss sang enka all night and told stories about how great life was before the economic bubble burst.

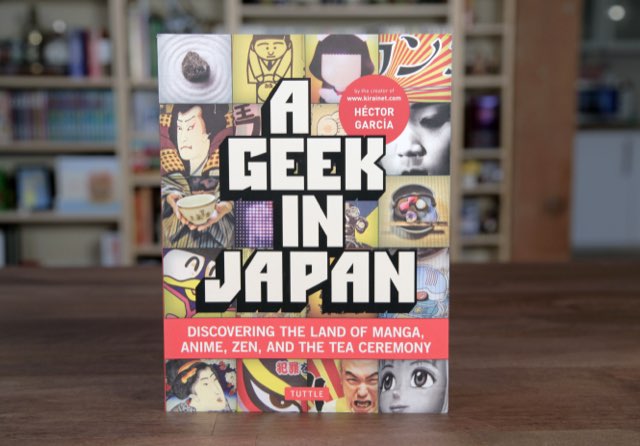

A Geek in Japan is kind of like a brain dump of everything about Japan, from the trivial to the profound, that lies behind those conversations. If all the material in this book is familiar, congratulations: you don't need it. And if you don't yet know most of what's in this book, it's a pretty good crash course, with a couple of big caveats.

Nearly Everything Under the (Rising) Sun

A Geek in Japan isn't what you might think from the title: it's not about geeks in Japan. It's written by a self-described geek in Japan, blogger Hector Garcia. So it's not a compendium of otaku stuff, although that is certainly covered. Instead it's a smorgasbord of bite-size to small-plate portions of just about everything. There are outlines of Japanese history digested down to a few paragraphs: if you don't already know the basic "samurai → Edo period → Meiji period opening to the west" arc of Japanese history, you'll get it here. You'll come away knowing about ukiyo-e prints, the concept of "continuous improvement" in business, and how the custom of sort-of arranged marriages still exists. You'll learn that the Yamanote line in Tokyo alone carries the same number of passengers as the entire New York City subway system in a day (and that if you choose wrong out of the 200 exits at Shinjuku station you may be a half-mile away from your destination.)

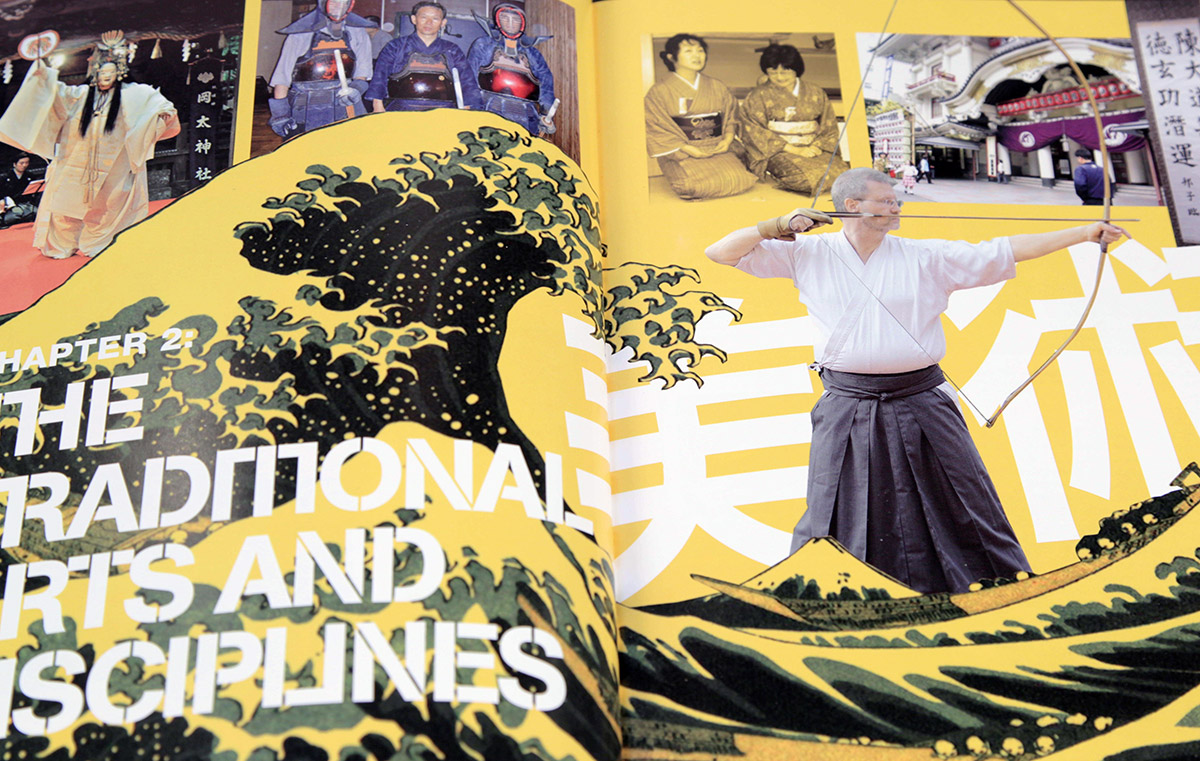

The author explains little details of everyday life that Westerners wonder about. Like why people wear face masks, or cover their hands with their mouths when they laugh, and answers the question "OMG why are there things that look like swastikas on this temple?!" There are nice illustrations and explanations of practical stuff that is useful for tourists, like photographs of all the parts of a temple and what they are. In general the book is heavy on photographs and nicely laid out.

Despite my severe reservations about some of the broad claims about language in A Geek in Japan that I will relate later, it has some fun practical points. For example if someone uses the word "chotto", despite the dictionary definition of "a little," they're trying to tell you "no."

Of course the otaku stuff is in here. And because we don't all come to our interest in Japan from anime and manga, this will be useful for some people. There are definitions of concepts like moe and lolita and whole chapters about the development of anime, manga, and TV and movies. Because the book was published in 2010, the popular culture sections may be a bit out of date. But much of it is history and many of the musical groups listed are still hugely popular, so they're still relevant.

While you can certainly find all of this information elsewhere, it's usually not all in the same book. And some of the details he relates go beyond the typical explanations.

When Garcia covers iconic cute animals he doesn't stick to the usual tanuki statue and waving cat. He mentions the sunfish, one of the many random animals Americans may not realize are popular in Japan. When he tells you that you can't visit the Ichiriki ocha-ya made famous by Memoirs of a Geisha, he points you to the Starbucks next door when you're likely to see the geisha coming and going.

When he talks about falling sales of manga, he describes how in the 90s, you'd usually see ten people in a train car reading manga, but now you'll see twenty on their phones, three on their hand-held game console and one reading manga.

He tells you how to order your sake at the temperature you want, and says "If you pull out the words atsukan or nurukan in a shabby restaurant full of old people, you'll be a big success!" Fun details like this make it clear that he's lived this life and isn't just reporting it second-hand.

Reasonable people could probably argue interestingly for hours about whether some of what's in_A Geek in Japan_is a recitation of stereotypes. It's hard to avoid stereotypes when trying to explain the difference between cultures. But I think you could say that they are actually valuable to know. For example, the more you know about Japan, the more you realize that there is a lot more divorce than you'd imagine from the stereotype. But the family life he describes of the mother obsessed with the children's schooling and the father who doesn't get home from work till midnight is probably what the Japanese themselves see as the typical family. That's a useful thing to know even if real life will often deviate from expectations.

The book concludes with a few chapters about travel, highlighting well-known places in Tokyo and his offbeat favorites, as well as what he considers essential places to visit elsewhere in country. The unique (and best) part of this section has to be item #1 on his list of General Advice For Travelers: "Don't Worry."

His suggestions on where to visit in Tokyo are a little heavily weighted to the otaku areas (no surprise), but on the whole it's a decent travel guide. I even came away with a couple of ideas for places to go myself, which I didn't expect. The info about technology (banks, phone, internet access, etc) is out of date, but some of that is changing so fast right now that any printed book, even a brand new one, is going to be behind the times.

Caveats

While it's encyclopedic, A Geek in Japan is written in the voice of one person. That makes it more enjoyable to read, but also means that there is no counterbalancing influence when he goes off the rails. There are two big problems in my opinion: most of what he says about language, and (often connected) the pronouncements he makes about "how Japanese people think" and "Japanese minds."

You should be immediately suspicious when anyone makes reference to "untranslatable" words or concepts. You'll notice that such a statement is always followed by translations. Which should make you wonder about the validity of the reasoning, don't you think? He does this early on in the book (page 6) so at least you know from the start to have your guard up whenever he turns to the topic of language.

Take the sidebar on page 39 where he points out that the kanji for "husband" consists of the radicals "main" and "person" and the one for "wife" is made up of "house" and "inside" and implies that this is a reflection of attitudes about gender that "remain strong in the Japanese mind." Yes, women's status isn't the same as it is in other countries. And there's no doubt a historical explanation about gender relations that explains why those words are what they are. But you'd need to write a whole psycholinguistics dissertation to prove that writing the words that way still influences people's thinking as opposed to being merely a historical relic. So without the footnoted references to any such research, you should take this kind of connection with a pillar of salt.

Such claims about language often dovetail with his other type of dubious pronouncement, as on page 13 where he claims that the kanji writing system "causes the Japanese to think differently from us" and that "their minds work on the basis of images."

It's too bad an editor didn't pull back on the reins here. Yes, Japanese culture is different. The habitual ways of approaching problems, interacting with others, etc, which have developed over a long history, are different. But human minds are human minds just as human beings are all equally human beings. To suggest that Japanese minds are different in some fundamental way is a slippery slope.

So be aware that you'll fairly often run into such pronouncements, not all of which have to do with language. For example, the claim that because of the influence of Zen, "those who have met a Japanese person will agree that almost all are calm and patient people." Again, culture may dictate that people behave this way on the surface, but I have no doubt that every Japanese person you meet is the same mess of emotions underneath as the rest of us. As for the claim that all Japanese people "love work above everything else" (page 65), you can judge how likely that is for yourself.

Verdict

While I think the two problems above are pretty serious ones, I'm also sure that any level-headed person can see through them. So you're capable of bringing some critical thinking to a book and still enjoying it and learning from it.

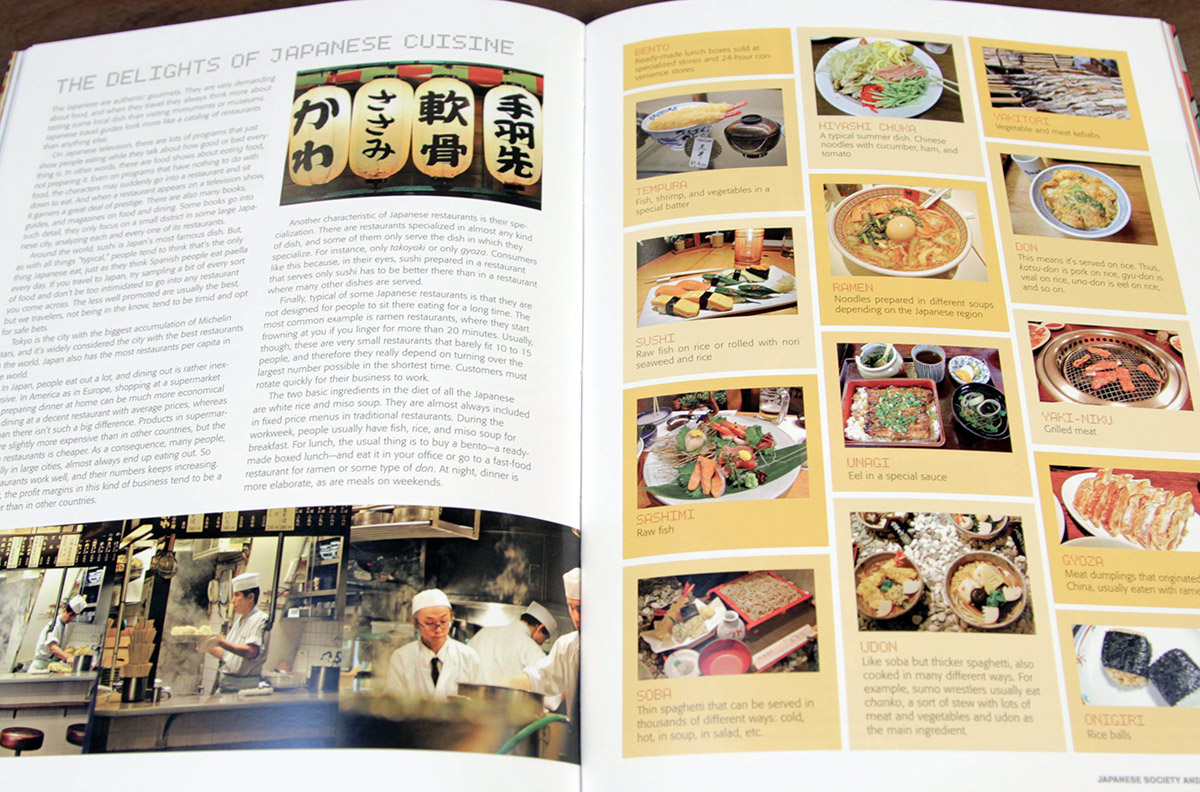

A Geek in Japan covers an unusual, maybe unique combination of many different basic things about Japan in a fun way. There a couple of gaps as far as subject matter, from my point of view. If it were my brain being dumped into a book like this, there'd be a lot more about food. He makes good observations about how central food is to the culture – that Japanese travel guides basically look like a catalog of restaurants and that there are food shows where people do almost nothing but talk about eating food. But if it's that important, shouldn't there be more than a couple of pages devoted to the subject? There's also is little or nothing about folklore, despite how important it is to manga and anime, which he covers at some length.

If you already have some expertise in a Japanese subject, you'll no doubt find similar things here and there that you think he's missed or is wrong about. But honestly in that case this book isn't meant for you. It's for the beginner to maybe intermediate level Japan-obsessive. If you're in the process of learning about Japan, you will eat this up. Don't take everything he says as gospel, but it's a good starting point for a whole lot of stuff you're going to want to know if you want to go to Japan someday.

This book would also be a great gift for someone who was going to Japan not as their own choice – say, in the military or following a spouse for a job – and had no previous interest in culture. Along with a lot of useful information and context, it also debunks common myths like "geisha are prostitutes." Probably not something Tofugu readers need to be told, but still a common association in most people's minds.

If you've been to Japan or are living/have lived in Japan, this book won't offer you much. But if you're new to Japan knowledge this book will help you a good deal. Just be sure to cross reference it with other sources some day down the line.