Over on Mutantfrog Travelogue, a post went up earlier this week called “My Japanese sucks and always will.” The post talks about how the author, somebody who’s a long-time student of Japanese, passed the JLPT 1, and has worked and lived in Japan for several years, still doesn’t feel like his Japanese is good enough.

As a student of Japanese, this is probably the most discouraging thing in the world to hear. You might think, “if even he doesn’t feel good about his Japanese, how can I?”

But if you go beyond the article and into the discussion, there’s a bit more than meets the eye.

Reading through the comments, there are plenty of people who empathize with the author, saying that they’re in a similar place.

One the other hand, there are lots of people who say that the author is too hard on himself.

The JLPT And Other Standards Of Japanese Fluency

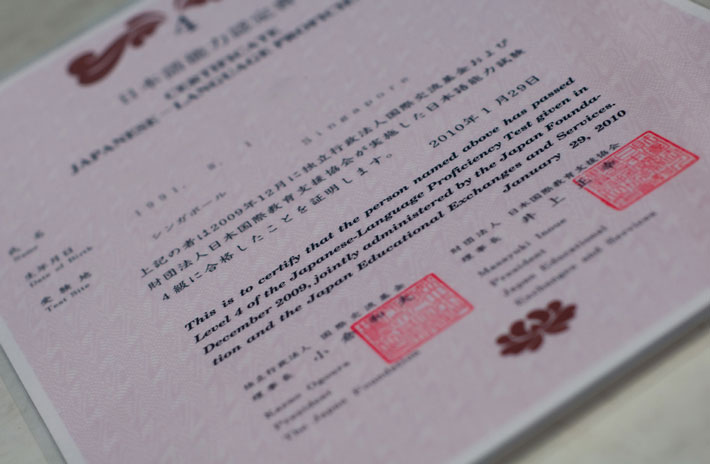

When you start talking about Japanese fluency, probably the first topic that comes up is the JLPT, or Japanese Language Proficiency Test for the uninitiated.

The JLPT is a test given a couple times a year by the Japanese government to foreigners who want to prove their Japanese language skills. When it comes to Japanese tests, the JLPT is the most widely-recognized and legit test out there.

Unfortunately, the JLPT isn’t a perfect test. It’s a multiple-choice test, so your written and verbal skills (which are important if you ever want to, y’know, talk to people) are never tested.

But if the JLPT isn’t the marker of fluency, then what is? This is where things get a bit hazy, and definitions of fluency become pretty arbitrary.

Everybody seems to have their own standards. Is fluency when you’re able to hold a translation job? Is it when you’re able to have a conversation with a stranger?

The weirdest standard of fluency I saw from the article comments was being able to have an affair with somebody entirely in Japanese. I guess that’s one way to see it.

If there’s disagreement on what it means to be fluent in Japanese, then it might be easier to figure out what it means to be fluent in your native language. How do you know that you’re fluent in your mother tongue?

Native Fluency

Even in your native language, there will be times when you forget words, stumble to find the right ones, and find words inadequate. Language is a big, complex, and imperfect form of human expression.

It’s scary to think about, but in your mother tongue, you only speak a very, very small piece of the language. Your accent and dialogue isn’t the norm everywhere, you don’t know the slang of every subculture, and you’re definitely not familiar with all technical terms.

So when people say things like “you’re only fluent in Japanese if you know the on’yomi and kun’yomi of all the Joyo Kanji,” think about what that means in your own language.

What would the English-language equivalent of this be? The closest I can think of would be learning a slew of SAT vocab words, then breaking them down and identifying their Latin roots.

I’d like to think that my English skills are pretty good, but that seems like a tall order. Would you expect any given fluent English speaker to do that much?

Don’t hold yourself to a higher standard in Japanese than you do in your own language.

What You Should Aim For

If you study Japanese and were discouraged by “My Japanese sucks and always will,” don’t be. This kind of frustration is normal when you’re learning something new, but you shouldn’t view it as a permanent setback.

Instead, you should see this as an opportunity to learn from people who have been studying Japanese longer than you, people who hit obstacles before you do.

As a Japanese student, set actionable, concrete goals for yourself instead of saying you want to be “fluent.” Fluency is a big, abstract goal that isn’t really helpful to anybody.

But if you instead set definite goals for yourself, you’ll be able to hit the mark.

To read more of the discussion, check out the article here, take a look at the Gakuranman’s Google+ post, or follow the conversation on Reddit.