It seems that even after years of study, a number of people taking formal Japanese classes and doing self-study don't get comprehensive coverage of the following particles: しか、さえ、and すら. By "comprehensive", I mean that, despite having similar functions, these particles are broken apart, taught individually and spaced out years apart. (Not always, but a lot of the time). Plus, the meanings often overlap, making the learning process feel, at times, redundant.

So I hope that this article can act as a sort of GPS device to let you know what kind of nuanced territory you're heading into and how to navigate it. I used the word "comprehensive" up there, but that just means I'm looking out for you – like comprehensive auto insurance. Trust me, this will be easy.

しか — "Only… and nothing more"

しか is on JLPT N5 prep guides, so even beginners should have this on their VIP lists – that is, the list for Very Important Particles. It was once explained to me that しか is like the mathematical ≤ or ≥ (it approaches a value and includes it, but just barely). It means "Only … and nothing more" or "nothing but…" as in the example:

- 私はローマ字しか読めない。

- I can only read romaji.

You can use this in a sentence easily: しか goes after the "only"-ified noun. Then, the verb or copula that comes after NEEDS to be negative.

Here's another example:

- 君しか見ていない。

- All I can see is you.

Both of these examples have been nouns in front of しか, but you can also precede it with the dictionary form of a verb. This particle is used at any formality level, and in written or spoken Japanese.

さえ — "Only" or "Even…" or "(did) not even"

I'll be honest: さえ still kind of confuses me. That's not surprising, given its history, which I'll get to in a bit. But look at the different ways it's used:

- 君さえいれば、ほかに何もいらない。

- If only you’re here, I don’t need anything else.

And this:

- 12月でさえ暖かった。

- It was even warm in December.

And this:

- ローマ字さえ読めない。

- I can’t even read hiragana.

So it can mean "even" sometimes, and "only" in other cases. Thankfully, if you look at the whole sentence, it's easy to see a pattern: when さえ is followed by a conditional, it means only. But when さえ is more of the main focus, it means even (and with a negative sentence, means 'not even').

さえ appears on N2 grammar prep lists. Make note of its unique formation: (adj. く) さえ、(na-adj. で) さえ、(noun) or (noun で) さえ、and (verb stem) さえ.

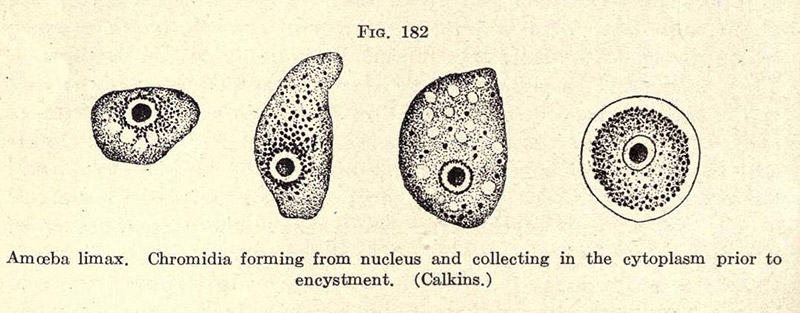

I mentioned that さえ's history might explain why it has a few different meanings. The way Haruo Shirane describes it in "Classical Japanese: A Grammar", the Heian Period particle さえ reached out like a hungry amoeba, gobbling up a number of other particles' meanings, including that of すら (225-226), described below. You'll see that the poor particle すら is still a bit sickly.

すら — "even"

According to Janet Ashby in "Read Real Japanese", すら is "a more literary equivalent of さえ" (93). I've got a problem with that simplification because there are a lot of conflicting usages of さえ, while すら seems to pretty much work like this:

- 彼女は自分の名前すら書く事が出来ない

- She can’t even write her own name.

In Colligan-Taylor's Living Japanese, an ecology grad student uses すら as she's being interviewed. So すら can be spoken, too, but probably sounds highbrow. It's sad that this particle is a little easier to use, but you won't encounter it as often as さえ.

すら doesn't appear on JLPT prep lists until N1, which is like… advanced land! Like さえ, though, it has a kind of unique formation, mimicking that of さえ.

Quantity? Or Surprise?

Often, these particles are thought of in terms of quantity or inclusivity. Which makes sense, doesn't it? "The only thing I can see is you" suggests a quantity or capable range to what the person can see. But one researcher, Shigeko Sugiura at Tokyo Daigaku (AKA TouDai, AKA the Harvard of Japan, AKA the TouDai Of America), published a linguistics paper about how さえ and すら (along with も in certain instances) are not focused on quantity but on expectations.

To understand that, let's talk a little about "implicature." Implicature refers to how what you literally say isn't always what you're implying and communicating. Part of implicature is the notion that if you don't specify some sort of scale in your words ("Some", "even", etc.), then such a scale may or may not exist but, regardless, isn't important enough for you to mention. The implied meaning behind "Some girls like boys" is very different from "Girls like boys." That last one is hetero-normative, while the first one implies that not all girls like boys. In other words, one provides a scale of possibility, while the other implies a massively black-and-white attitude. These are important distinctions to make to really express yourself and your thoughts, no matter the language.

But we're talking about 'even', not 'some', and Sugiura argues that さえ、すら、and mo も aren't based around quantifiable scales (like 'all', or 'some'), but expectation-based scales. In other words, when an event occurs, does it fall inside the realm of the speaker's expectations? This realm ranges from the highly probable to the least likely, but when it comes to using さえ and すら, the even-ified event won't be anywhere on the radar.

Compare these:

- メアリーさんはなっとうを食べた。

- Mary ate natto.

- メアリーさんはなっとうさえ食べた。

- Mary even ate natto.

- メアリーさんはなっとうさえ食べなかった。

- Mary didn’t even eat natto.

The first sentence is perfectly neutral. Nothing remarkable about Mary's eating natto. The second suggests that Mary's doing some crazy stuff, sure, but what's really crazy and what wasn't expected is that she ate natto. And in the third, Mary is in a situation, maybe a homestay, which demands a number of actions, and Mary didn't even do the most likely thing: eat natto.

The second and third sentence, then, fall outside the realm of expectations.

The Takeaway

Let's put it all together: If someone's doing crazy things (or not doing the most normal, expected, bare minimum of things), さえ、すら、and mo も can all go in the blank below:

[Subject]は [noun] __ [verb/copula (+ any formality, time, and negation mods)]

Such as:

- 私は日本に旅行したとき、1千円も使わなかった!

- When I traveled in Japan, I didn’t even spend a thousand yen/~10 USD/ ~7 Euro.

That's pretty much impossible. Was this person camping the whole time and bicycling everywhere? Were they an honorary guest of the emperor? This is what Sugiura meant by an expectational scale. Sometimes there are quantities involved, but using さえ and すら and mo も this way suggests something crazy is going on (back to Mary's eating/not eating Natto). It might depend on the situation whether something crazy is actually happening. But if the person uses these particles, they're implying that at least they believe it's crazy stuff.

Note, the "exceeding expectations も" is functioning in a different way than the adding kind of も, which you see in sentences like:

- 読書が好きだ。普通は本を読むけれども、たまに漫画も読む。

- I enjoy reading. Generally I read books, but every now and then I read manga, too.

See, I told you this would be easy. Some of these particles could get really confusing, but I think they're worth practicing. The above formula particularly should give you an easy way to change up your conversational toolbox.

So What About だけ?

I used to act like だけ could be used in all the same times I would use the English "only" and, woh, did I confuse Japanese people and get laughed at. I'm not saying しか changed my world, but the more I learned, the more I was basing definitions of words and particles by their context, not by their translation.

さえ、and すら, meanwhile, have meanings that overlap with particles you definitely know, such as も and だけ, so if you learn them separately, maybe you'll just think "I already know one way of saying 'only' or 'even'. Why bother learning another?" To which I say: Translations don't capture usage. You've already probably learned this with 好き and how it 'means' 'like'/'love'. You know that it's way more complicated than that. So once you're ready, give さえ or すら some attention, and tell me what it's like. If you've already taken that road trip, though, share your experience on Twitter.