I'd like the start this article with a quote from "Art & Fear", a book written by David Bayles and Ted Orland.

The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality. His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the "quantity" group: fifty pound of pots rated an "A", forty pounds a "B", and so on. Those being graded on "quality", however, needed to produce only one pot – albeit a perfect one – to get an "A".

Well, came grading time and a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the "quantity" group was busily churning out piles of work – and learning from their mistakes – the "quality" group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.

These two paragraphs are what inspired Tofugu's 500 Japanese Sentences (which later became 4500 Japanese Sentences). It's unfortunately not currently available, but it's a workbook that gives you a lot of Japanese sentences to translate, based off of words that are ordered by frequency of use. The focus, of course, is all on quantity, not quality. If you don't know how to translate something and can't figure it out quickly, move on. If you're confused, move on. If you're stuck, move on. Do what's at your ability level and what's slightly above it and skip the rest. It'll be there waiting for you on your second run through.

This goes against what most people are taught in school. In fact, there's a popular saying you've probably heard a lot: "Quality over quantity." It turns out, though, that quantity creates quality, and this can be applied to pretty much any skill you're trying to develop, Japanese included.

Let's Make Some Assumptions First

To understand why quantity trumps quality, we first have to come to a belief about how one acquires language. Today we're going to look at one particular hypothesis known as the "Input Hypothesis" by Stephen Krashen. That being said, it is just a hypothesis (not a thesis or a law!). But much of my support for it does come from personal experience, the experience of others, and a few poor souls that I've experimented on.

There are five parts to this hypothesis, but we're only going to look at one. It is:

Input Hypothesis: A learner's progress in their knowledge of the language when they comprehend language input that is slightly more advanced than their current level. Krashen called this level of input "i+1", where "i" is the language input and "+1" is the next stage of language acquisition.

I'll admit, there are some parts to this set of hypothesis that I don't like, but there are other ideas that I love. This will probably change tomorrow, but for now let's roll with it and take a look at what this has to do with quantity over quality.

+1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1

The Input Hypothesis says that progression in the language that you're learning comes from when you can comprehend language input that is slightly above your current level. Comprehending something that is +1 above your current ability level isn't all that hard. It's only +1, after all. Comprehending something that is more than +1 is, according to this hypothesis, not a good use of your time. Trying to comprehend a sentence that is, for example, +10 above your current level likely won't teach you anything new. Mostly it'll befuddle you and make you frustrated.

While I don't think this is true in every situation, I do see where he's coming from. I follow a very similar philosophy with the lessons I write. Everything is +1 +1 +1 +1. Many small steps that build on each other. But, this is true when you look at the bigger picture too. Cut out some of the outliers and exceptions to the rule / hypothesis, and you see a lot of real-life examples pop up. Are any of these you?

Kanji Learning:

-

Quality: To learn a single kanji, you learn every single meaning and reading, and you also learn how to write the damn thing. With your precious hands. Arguably, these are all important things, and I do think that it's important to learn them all eventually. The "quality" group will learn kanji like this, one by one by one, and it will probably take a while.

-

Quantity: Instead of learning everything, you learn the bare minimum so that you can hurry up and learn the next kanji. In extreme cases, that just involves you learning the meaning of the kanji and that's it (Heisig's). In our corner (WaniKani), usually we have people learn just one meaning and one reading.

You skip a lot of information while studying with the quantity over quality method. But, there's a funny thing with kanji study that I see in student after student after student: the more kanji they know, the easier it is for them to learn the next kanji. There's a few reasons for this and I won't go into too much detail, but experience does beget experience. By cutting the fluff (removing less important readings, meanings, and handwriting) you end up with way more kanji "done" in the same amount of time.

This is important because you need a lot of kanji to be able to read real Japanese. Think of it this way. Say you're reading Japanese text (a blog, cooking site, book, manga, etc). You come across a compound jukugo word. If you don't know the meanings of the kanji already, you have to look that up, the readings, and then the meaning/reading of the word. Certainly not +1 (more like +4). That means it is too high above your level for you to naturally comprehend it. But, say you run across the same word and you know the meanings and readings of the kanji that make up the word. All you need is to look up the meaning of the word because you can read it already. Also, the meaning of the word is related to the meanings of the kanji. Something like that is +1. Or better yet, you guess the meaning of the word based off the meanings of the kanji. Without having to look anything up you know the meaning of that word. That's an easy +1.

Sure, you can do this in the quality camp as well. But, the opportunities for this to happen go down dramatically. Reading Japanese only to have to look up 75% of the kanji/words on the page is a very frustrating experience. But if you go the quantity route with kanji, you're setting yourself up to do a lot less of that. With quantity comes quality.

Sentence Studying:

Now let's look at sentence studying. The idea here is that you're using sentences to study / improve your Japanese. You read them and you translate them. Let's assume you're at an intermediate-ish level or above, or at the very least the sentences are tailored to your level. That being said, there are way fewer beginner-level sentences out there to study (compared to the plethora of real Japanese sentences that exist).

-

Quality: You spend a lot of time on each sentence. You try to learn and memorize every single word. You make sure every bit of grammar is absolutely perfect before moving on to the next one.

-

Quantity: You don't spend much time on each sentence. You'll look up grammar the best you can. You look up words too. But, if you get stuck you don't worry about it. You're trying to stay at or slightly above your ability level. Any part that's not, you just skip.

The important thing here is that you're moving on quickly. You don't worry about memorizing every word. If it comes up enough you'll start to remember it, after all. If you're at the right level, studying with sentences is an excellent way to get a lot of +1 feedback loops. The hard part is embracing the idea that "It's okay to move on. Quickly."

The great thing with this is that you'll start to see patterns, which is only possible when you focus on quantity. Seeing 500 sentences over the course of a month (quantity) is much different from seeing 500 sentences over the course of a year (quality). Patterns get too spread out to see when you take too long to move on to the next sentence.

Also, while we're buying into the Input Hypothesis, think of sentence studying in this way:

In a single sentence there might be one or two things that are a +1 to your current skill level (if you're lucky). There will also be things that are +5 and +10. If we're assuming that these things don't really help you to get better, then spending all that extra time on a sentence to figure out the +5 and +10 stuff isn't going to help you as much. If you brute force through a lot of sentences, you'll see a higher number of +1 improvements. In the long run, you're coming out way, way ahead. Then, when you finish, come back to the stuff you didn't understand. I think you'll find that the things that were +5 before are more like +1.

Kanji and sentences are just a couple of examples. If you think about your Japanese in this way, you'll see that it's true everywhere else you look too. If you want to get good at speaking… well, you should probably speak. A lot. Then do it some more. Don't get hung up on being perfect because it will slow you down (and make you scared to speak). This goes for reading, writing, listening, and every other aspect of Japanese learning. Think about what you're having trouble with right now. Does the cause have anything to do with your focus on quality instead of quantity?

Oh, That Immersion Thing?

At this point you might be thinking about how to add quantity to your Japanese studying routine. What about immersion?

Well, immersion is just quantity over quality pushed to the extreme. You get so much friggin' input that you can't help but learn something. This is simply because you're getting a lot more +1 opportunities. It is the brute force of brute force strategies, and it works. There's a reason why most people say immersion is the best and easiest way to learn a new language.

But, immersion isn't realistic for many people. Whether that means creating an immersive environment for yourself or going to Japan to live there, that's usually not an option.

So we have to come up with a compromise… one that favors your Japanese progress. To do that, you must…

Find A Good Teacher

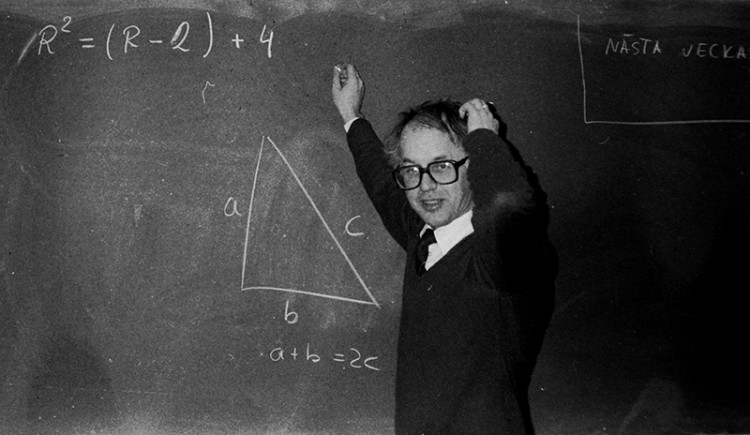

I'm not necessarily talking about someone who stands up at the front of a classroom or sits across a table from you, though sometimes that will be true. I'm also including "you" in this list. And textbooks. And the raving posts of Japanese learners on various message boards. Teachers comes in many different shapes, sizes, and bytes.

But, there is a good way to figure out which ones are good and which ones aren't. It comes down to quantity over quality and how they go about applying this to your studies.

-

A good teacher won't make you perfect. They'll know what is out of reach and instead focus on the things that will incrementally make you better (+1).

-

A bad teacher will focus on perfectionism. This will make you neurotic. It will make you too worried to make a mistake. You'll slowly focus on trying to figure out how to not screw up, which will usually result in you speaking and using Japanese less and less. You'll try to make a few things perfect but everything else will be nonexistent.

-

A good teacher will let you make mistakes, and lots of them. As Michael Jordan once said: "I've missed more than 9000 shots in my career. I've lost almost 300 games. 26 times, I've been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I've failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed." Mistakes are an important part of learning, and if you don't make enough of them you can't get better. Actually, many studies show that mistakes in grammar are actually just a part of the learning process. They're a step on a set of stairs. Without them you can't move up.

-

A good teacher will be smart about the quantity they give you. It should be the thing you need to level up, not just a bunch of stuff for the sake of being a bunch of stuff. Quantity is good, but it stops being useful when there are very few +1 opportunities inside.

-

A bad teacher will tell you to learn something "because that's how it's always been done." This will often be +10 above your ability level. You'll hear things like "Just learn it!" but there won't be any reason behind it. It won't be broken down into +1 pieces. As a beginner, it's really hard to break something up into +1 sized chunks. That's the teacher's job, at least until you get a little better at this whole "learning Japanese" thing. When this happens, you spend a lot of time trying to figure out this +10 task when you could have been spending the same amount of time making 100x +1 progress.

-

A good teacher makes you comfortable to use your Japanese more. To do this, they have to make you feel less bad about messing up. If they can do this, you'll use your Japanese a lot more, get better, and be fluent in Japanese faster. This is the biggest difference between a quantity and quality focused teacher.

The list goes on and on, I'm sure. Being able to know when and how much quantity you should apply to your studies is difficult. To figure it out, you have to try a lot of different things sometimes. A good way is to ask the pros what they wish they did more of when they were first starting out. With Japanese, I think a lot of people might say something like "I wish I knew more kanji". In this way it's easy to identify what you should get a lot of.

How do you apply quantity to your Japanese studies? Or better yet, where can you do a better job applying quantity instead of obsessing on quality? I'm sure many other people will completely disagree with all of this as well, so send us some tweets with your opinions.