If you're reading this, I'm assuming you already know the words 中 (naka) and 内 (uchi). But do you really know them? Most dictionaries list "inside" as the first definition for both 中 and 内. Our kanji learning app WaniKani also teaches the primary meaning of both 中 and 内 as in "inside."

However, despite enormous overlap in their meanings, they are not always interchangeable! For example, to say "inside the box," you'd usually use 中 rather than 内, as in 箱の中.

That's because, while they do both mean "inside," they don’t refer to quite the same "inside." You didn't realize there could be more than one inside? You're not alone! Read on to explore the differences using images, and then see how your new understanding applies to a bunch of different examples.

Prerequisites: This article assumes you already know hiragana and katakana. If you need to brush up, have a look at our Ultimate Hiragana Guide and Ultimate Katakana Guide. It also assumes you’re already familiar with 中 and 内, and you’re ready to delve into the intricacies of what makes them different.

Concepts of 中 and 内:

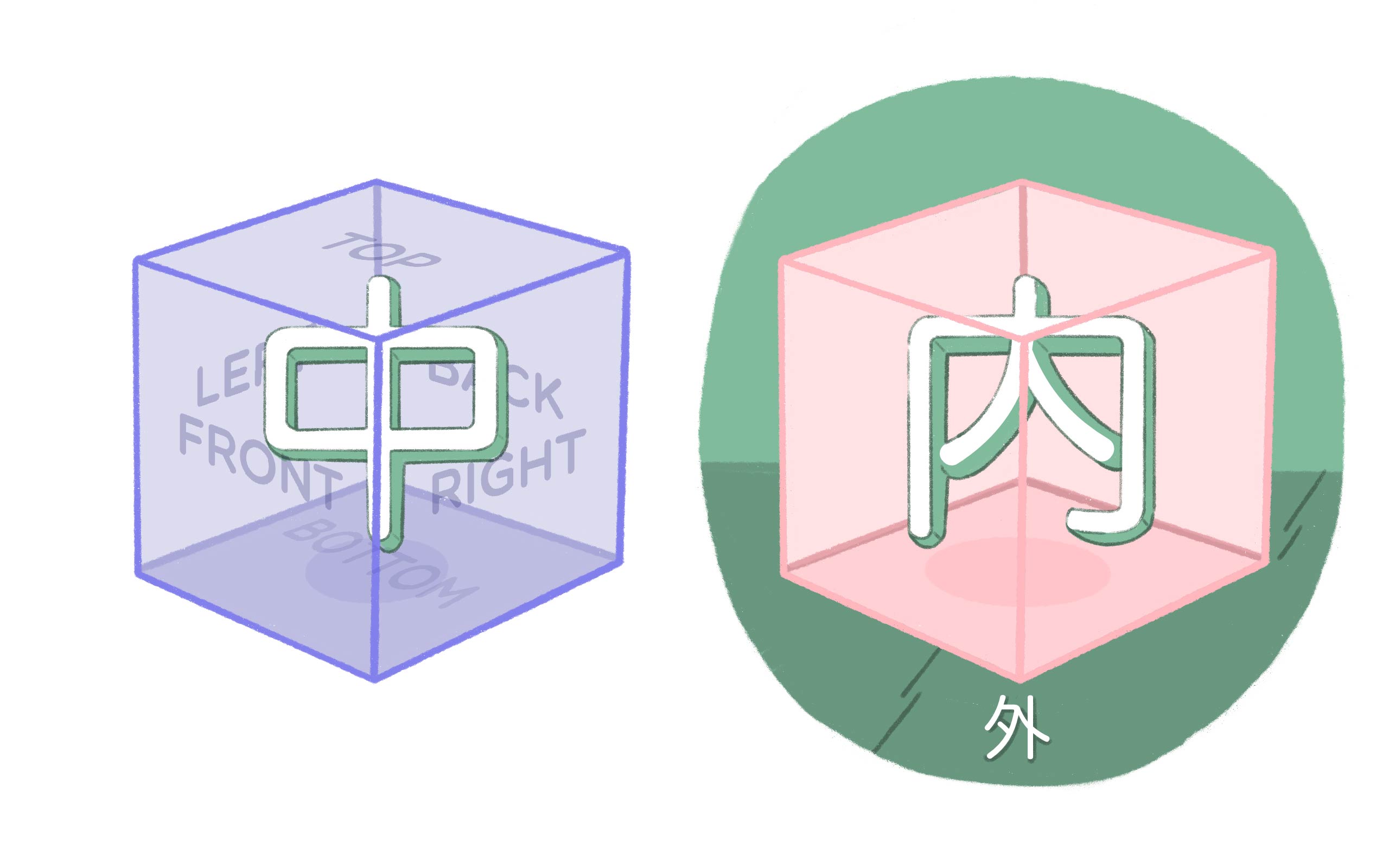

So what’s the difference between 中 and 内, really? To understand this, please take a look at the two images below.

In the left image, you can see 中 is inside the box, while top and bottom, front and back, and left and right are labeled on each side of the box. This is to show that 中 represents the center or the middle, and it can also mean the entire inside. In short, 中 is simply pointing to the inside position in relation to the other positions.

In the right-hand image above, the inside of the box is pink and everything outside is green. This is because 内 always implies a contrast with 外 (outside). You are highlighting the inside of something as opposed to the outside. So 内 points to the fact that something is "within a surrounding." It does more than just pointing to the central or internal position.

Now let’s check out examples for 中 and 内.

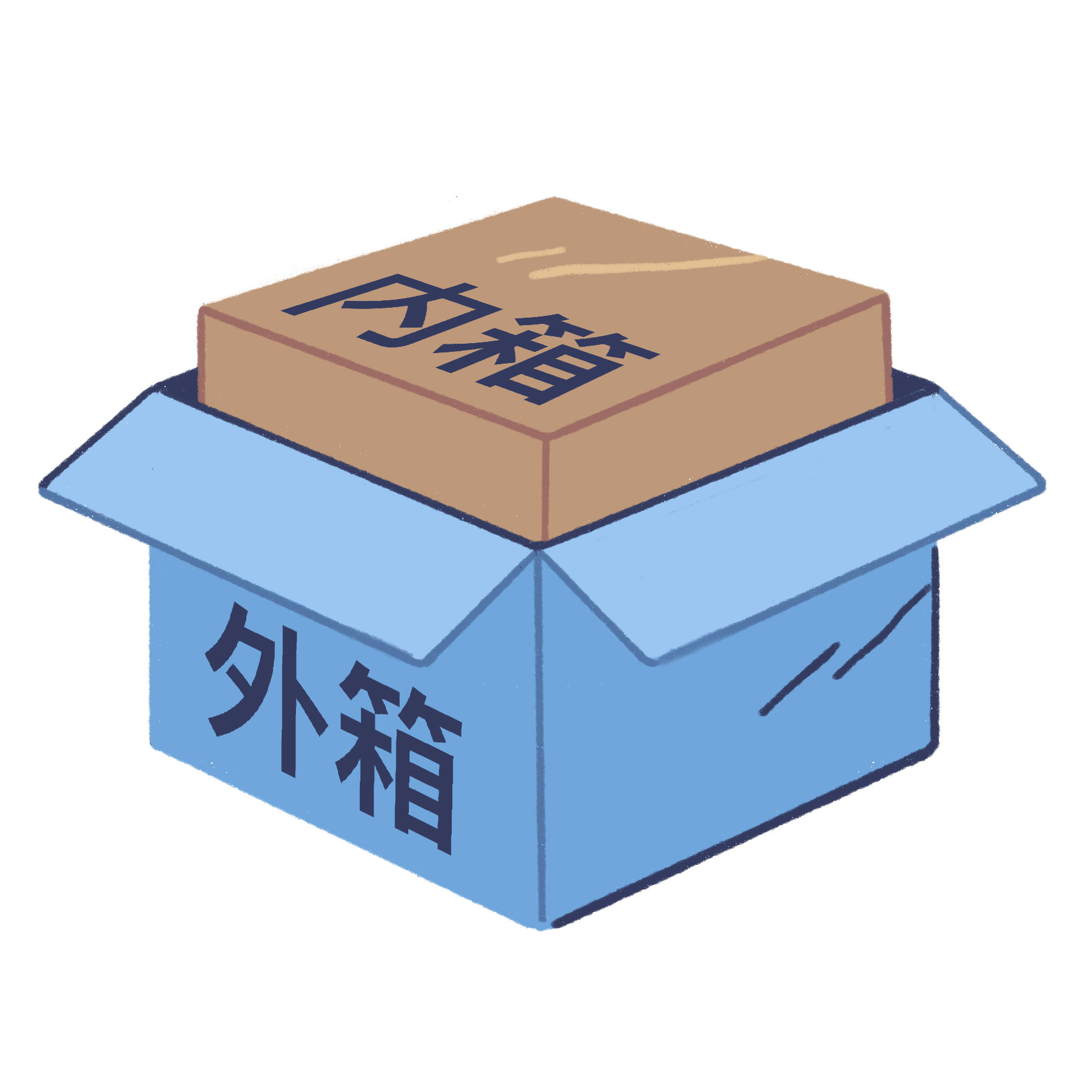

So imagine you received a gift box. You open the lid, and there’s an additional box inside it. You can say, "there’s another box in the 中 of the box."

- 箱の中にもう一つ箱があります。

- There's another box inside the box.

In the same vein, 中 can also refer to a middle position, because it’s basically the inside position in relation to the both sides, edges, or ends of something. So your middle finger is called 中指 (middle-finger) because it’s the middle thing of five things.😜 When it comes to size or grade, 中 also stands for something that's in the "middle," relative to other things, as in 大中小 (large-medium-small) or 上中下 (upper-middle-lower), as it points to the medium status in relation to the other sizes or grades. So for example, 中ジョッキ is a medium beer mug, and 中学生 is a middle school student.

For 内, let's go back to the gift box example. You open the lid, and there’s the second box inside. You might refer to the inner box as 内箱 or 内側の箱 and to the outer box as 外箱 or 外側の箱, because in this case you're treating the two boxes as a pair.

- 外箱は青ですが、内箱は茶色です。

- The outer box is blue, but the inner box is brown.

Choosing Between 中 and 内

Now that you’ve learned the basic concepts of 中 and 内, let’s apply these concepts to some real world examples. We’ll move through a range of different contexts to help with your understanding of 中 and 内. We’ll first explore how 中 and 内 are used with physical spaces, and then we’ll also talk about how they are used with a time period!

中 or 内 with Physical Spaces

中 with Physical Spaces

In its most common use, 中 refers to the inside of something. Imagine you receive another box, and open it to find a ukulele. To describe this situation, you can say:

- 箱を開けると、中にはウクレレが入っていた。

- When I opened the box, there was a ukulele inside.

Here, 中 is your choice because you are simply talking about where the ukulele is located. There is no contrast with the outside of the box, so you wouldn't use 内.

Let’s take a look at another example. Imagine you are getting ready to go out, and you put your smartphone in your bag. In this case, you'll want to use 中 because you are simply pointing to the location of your smartphone. Again, no inside/outside contrast here, we're indicating the position, pure and simple.

- スマホをかばんの中に入れた。

- I put the smartphone inside the bag.

In the same way, if you are going for a walk and feel a stone in your shoe, you may say:

- くつの中に石が入っちゃった。

- There's a stone in my shoe.

(Literally: A stone entered inside my shoe.)

Again, you're not contrasting the stone inside your shoe with all those stones on the path. You're simply stating the location of the stone, so 中 makes the most sense here too.

So far so good? To consolidate your understanding, let’s examine a couple more examples. Imagine you belong to a basketball club. Usually, your team practices in the school yard, but was raining today, so you played basketball in the gymnasium.

- 雨が 降っていたので、 体育館の中でバスケをした。

- It was raining so we played basketball inside the gymnasium.

At first glance, this example seems to be making a contrast and 内 may feel more suitable because you chose the inside of the gymnasium for playing basketball as opposed to the outside. If you used 内, however, it would sound like you're highlighting the walls of the gymnasium as a boundary separating the inside from the outside. It puts emphasis on within the boundary (the gymnasium) and it sounds a bit odd with this example, similar to if you said "we played within the gymnasium" in English.

In this sentence, you are still simply pointing to the place where you play basketball. It may be making a contrast to the outdoors in general, but there is no stress on the dividing line. Hence 中 is your choice!

Okay, now the last example for this section. Let’s say people belonging to a dance club didn’t care about the rain and they danced outside. To say "they danced in the rain," in Japanese we consider it as dancing inside the rain, or in the middle of the raindrops. To refer to this, you’d use 中, as in:

- 雨の中でダンスをした。

- They danced in the rain.

Yet again, you're describing your location as being in the middle of the rain. There is no implication that there are other places where it's not raining, so this should be 雨の中. There is no comparison between 内 and 外 here!

内 with Physical Spaces

As you've seen, 中 is used simply to indicate a location. When 内 is chosen, on the other hand, there is a comparison between 内 and 外.

Unlike 中, which can be used as a standalone word in various situations, 内 is more commonly used in jukugo (words that are made up of two or more kanji) when referring to physical spaces. These jukugo words usually come in pairs: one half of the pair is 内 plus another kanji, and the other half is 外 plus that same kanji.

One of the most common of these pairs is 内側 and 外側. The kanji 側 means "side" and it makes it clearer that you are referring to either the inside or the outside of something. So if your teacher instructs you to write your name on the inside of your baseball cap, she may say:

- キャップの内側に名前を書いてください。

- Please write your name inside the baseball cap.

We use 内 and not 中 here because you are not talking about the middle of your baseball cap, but rather the inside surface as opposed to the outside surface.

You'll also often hear 内側 in announcements on Japanese train station platforms, as in:

- 危険ですから、 白線の内側でお 待ち下さい。

- For your safety, please wait behind the white line.

(Literally: Because of the danger, please wait inside the white line.)

In this case, 内側 refers to the area behind the white line on the platform edge, and there is an implicit contrast with the other side of the white line, which is considered 外側.

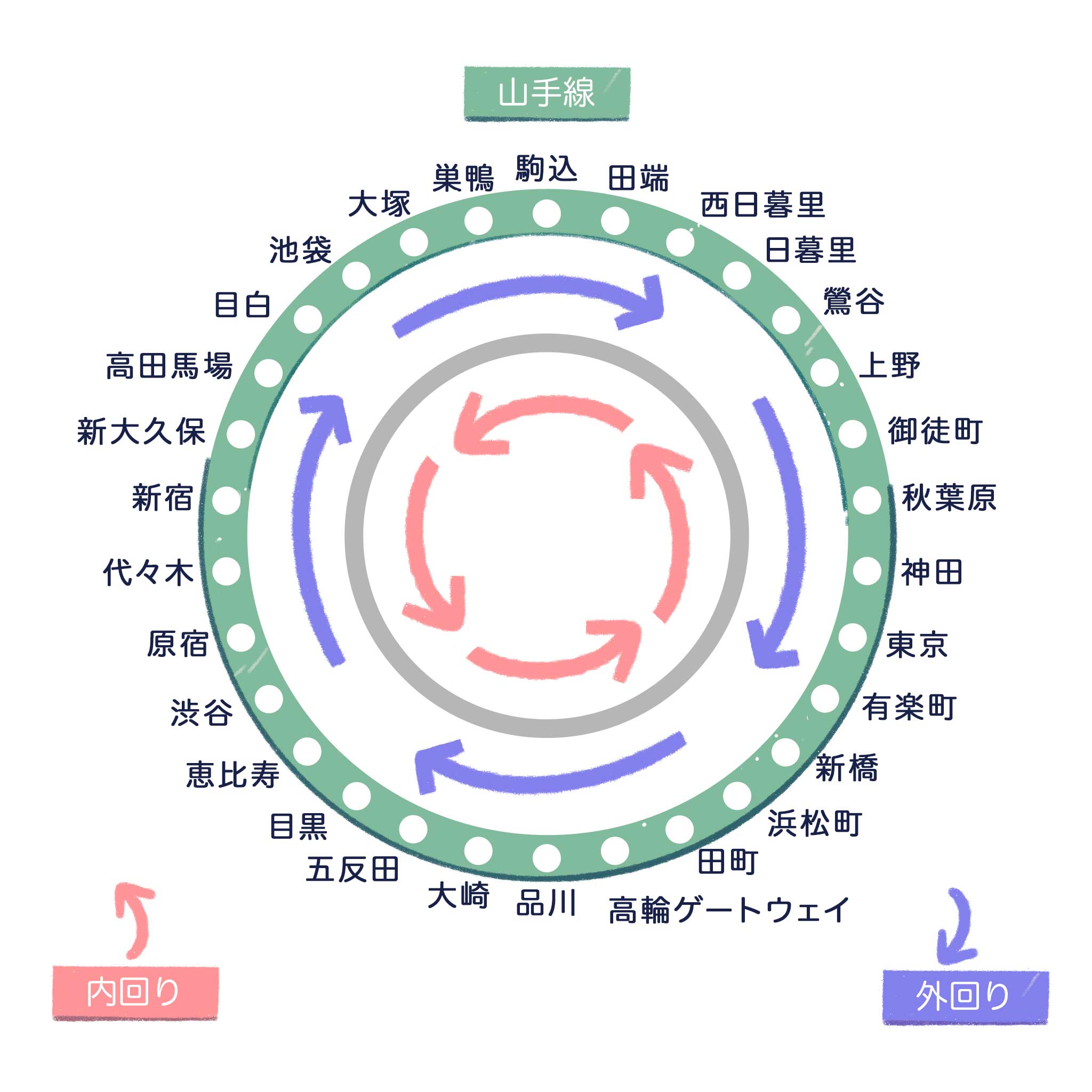

Another common pair related to Japanese trains is 内回り and 外回り. The word 回り means "rotation," and 内回り means "the inside track" as opposed to 外回り, which means "the outside track."

This pair is often used to refer to double railway loop lines, like the famous Tokyo loop line, the Yamanote-sen, and its Osaka counterpart, the Kanjō-sen.

As well as other kanji, 内 can also be combined with whole words to form jukugo.

For example, if 内 is combined with the word ポケット, as in 内ポケット, it means an inside pocket. Although an outside pocket can be referred to as 外ポケット, especially when you are making a comparison, it is more commonly just called ポケット.

This is probably because, just like in English, the word ポケット tends to make us think of a pocket on the outside. If we're talking about an inside pocket, we usually need to specify that, and there's generally an implied contrast with the outside pocket. Maybe you want to specify that you are talking about your hidden, inside pocket that you can hide your secret stuff in.

So to sum it up, when you want to highlight the inside half of a pair, you’d probably go with 内!

中 and 内 with Physical Spaces

I hope you are getting the hang of it. Now let’s look at some examples of where both 中 and 内 are possible. The first example is yet another train-related one. You may hear the following announcement when you are in a Japanese train:

- 車内での 通話はご 遠慮ください。

- Please refrain from making phone calls in the train.

Here, 車内 refers to the inside of the train, and its opposite is 車外, meaning "outside the train." 1 Unlike the earlier gymnasium example, putting emphasis on the boundary between the inside and outside of the train car makes more sense here. It strengthens the point that you should not make phone calls inside the train, while implying that it’s okay to do so outside the train. This nuance is actually very subtle, and most Japanese speakers probably aren't even aware of it, but the implication is there nonetheless.

You could also use 中, as in 電車の中, and it simply indicates you are neutrally talking about the location in that case. However, train announcements always use 車内. Why? This actually has nothing to do with the nuance distinction between 内 and 中. It is simply a question of register: jukugo words (that's words consisting of two or more kanji) tend to sound more formal, so the use of 車内 rather than 電車の中 makes the announcement sound more official. Hence, the jukugo word 車内 is more suitable for official train announcements, while you can either use 電車の中 or 車内 in daily conversation depending on how casual or formal you want to sound.

Just like Japanese train conductors asking people not to make calls in the train, teachers may tell students not to run inside the school building. In this case, they can use both 中 or 内, as in:

- 学校の中で走らない!

校内で走らない! - Don’t run inside the school!

Again, 中 neutrally indicates the inside of the school, whereas 校内 highlights the boundary between the inside and outside of the school. Like the train announcement example, the differences between them are quite subtle and word choice may depend purely on the level of formality the person wants to convey. For example, teachers may go with 学校の中 for younger students, whereas 校内 may be selected for older students, since teachers tend to use more formal language with older students. There's also a question of understanding here, as younger students may understand 学校の中 more easily than 校内.

Our next example is about a soccer rule:

- ペナルティエリアの中で 反則をすると、ペナルティキックになる。

ペナルティエリア 内で 反則をすると、ペナルティキックになる。 - If you commit a foul in the penalty area, there'll be a penalty kick.

To refer to the inside of the penalty area, you can use both 中 or 内, but the nuances are slightly different. If you use 中, it simply indicates you are pointing to the inside of the penalty area, and that works just fine. On the other hand, 内 highlights the foul being made within the boundary of the penalty area. So if you’d like to put emphasis on the contrast between the penalty area and non-penalty area, then you might go with 内.

What if you are talking about a bigger area, like a town? So let’s say your brother is the tallest person in the town where you live. When you say "in the town" like this, you’re not making a comparison between people inside and outside of the town. So, out of the two options, 中 is the most likely, though 内 can work too. 2

- 兄はこの町の中で一番 背が高い。

兄はこの町内で一番 背が高い。 - My brother is the tallest in this town.

The reason 内 also works is because you are technically highlighting the whole area of the town as a range of height comparison. It also inadvertently compares with the outside of the town, implying that he may not be the tallest person in the country, but he is the tallest in town. 3 So again, this comes down to personal choice and the nuance you want to convey.

The next example may be a little more challenging. Imagine you get into a quarrel with a family member. It upsets you, and you run into your room, slam the door, and lock it from the inside. In this case, either 中 or 内 can be used, as in:

- 中からカギをかけた。

内からカギをかけた。 - I locked the door from the inside.

When using 中, you are simply indicating the location from which the door was locked. If you use 内, it highlights the door as the boundary between your room and the rest of the house. Choosing 内 could perhaps characterize your perception of the events that just occurred, and your mental and emotional state in response to it, such as feeling defensive towards what is outside of your room.

Note that we used 内 alone in this example. It actually feels a bit archaic to use 内 alone when talking about physical spaces, and it generally establishes a literary or poetic tone. Unless that’s the style you’re aiming for, it’s more common to use the compound word 内側, which we saw earlier also means "inside." So, if your little one locked you out and you are describing the situation objectively to your partner, either 中 or 内側 is probably your choice! If you're writing poetry, or writing in your diary about your emotions and want to add some literary flair, go ahead and use 内 on its own!

It's worth mentioning, though, that there are situations where the concepts suggest that both should be possible, but quirks in the way language develops mean that only one is actually used. For example, if your children are hyper and screaming in the house, you may tell them:

- ⭕ 家の中でさけばない!

❌ 家内でさけばない! - Don't scream inside the house!

In this case, you are telling your child that it’s not okay to be loud inside the house, implying that it may be allowed outside. Even if you want to highlight this contrast, 内 is not an option.

This is because 家内 is already established as a completely different word. It is a slightly old-fashioned way of saying "my wife," so it cannot be used to refer to the inside of the house. Cases like this are the exception rather than the rule, though, and you'll get to know them over time.

中 or 内 with a Figurative Space

Although 中 and 内 are usually used in relation to physical spaces, they can sometimes be used for figurative spaces too. For example, if the concept of 中 and 内 still feels jumbled to you, you can use 中 (not 内😉) and say:

- 頭の中が 混乱している。

- My thoughts are jumbled up.

(Literally: The inside of my head is in confusion.)

In this example, 中 is your choice because you are only referring to the confusion happening inside your head, and not making a comparison between your jumbled up thoughts and those of other people.

Let's have a look at another example. Imagine you are in the mood to make up a cheesy song, and your mind is full of corny lyrics. You may feel embarrassed about your lyrics and want to keep them private, and think:

- 誰にも心の中をのぞかれたくない。

誰にも心の内をのぞかれたくない。 - I don't want anybody looking into my mind.

Although 中 is more commonly used, you could use 内 with this example. This is because in Japanese, your 心 (heart or mind) is thought of as a place where natural, spontaneous thoughts or feelings occur. Thus, 心 is something close to the core of yourself, and you could use 内 to highlight those deep inner feelings. You can probably see how literary and poetic nuances mentioned earlier are built into this expression, and using 内 as a standalone word would be consistent with that.

The last example in this section is a quirky one for fun. This figurative use is something you may come across on social media. Many companies have a social media account that represents the company, but of course there’s always an actual person who operates the account. To refer to the person behind the social media account, we use 中!

- こんにちは、トーフグのツイッターの中の人です!

- Hello, I’m the person behind Tofugu's twitter account!

(Literally: Hello, I’m the person from inside of Tofugu's twitter account!)

Here, again, there’s no comparison between the person in charge of the account and other people. What they’re doing is simply referring to themselves as the person who operates the account, so 中の人 is the way to go!

Sometimes this use is expanded to mean more than the person behind a social media account. For example, 中の人 could refer to an employee of a company, a student of a particular school, a member of an organization or a family group, or basically anyone that is "inside" a group of any kind. If used like this, 中の人 adds the nuance that the person is an insider, and therefore likely benefits from privileged knowledge or perspective.

中 or 内 with a Time Period

中 and 内 can also be used to refer to time periods, and in this case the structure and nuance are a little different. For example, to talk about something you expect to be done this year, you can combine both 中 or 内 with 今年 (this year). That is, both 今年中 and 今年の内 could be translated as "this year."4

However, 今年中 focuses on the whole of this year, and it can mean either "sometime this year" or "by the end of this year," depending on the context. On the other hand, 今年の内 refers to "this year, before it changes to next year," so the translation "by the end of this year" would always work for this.

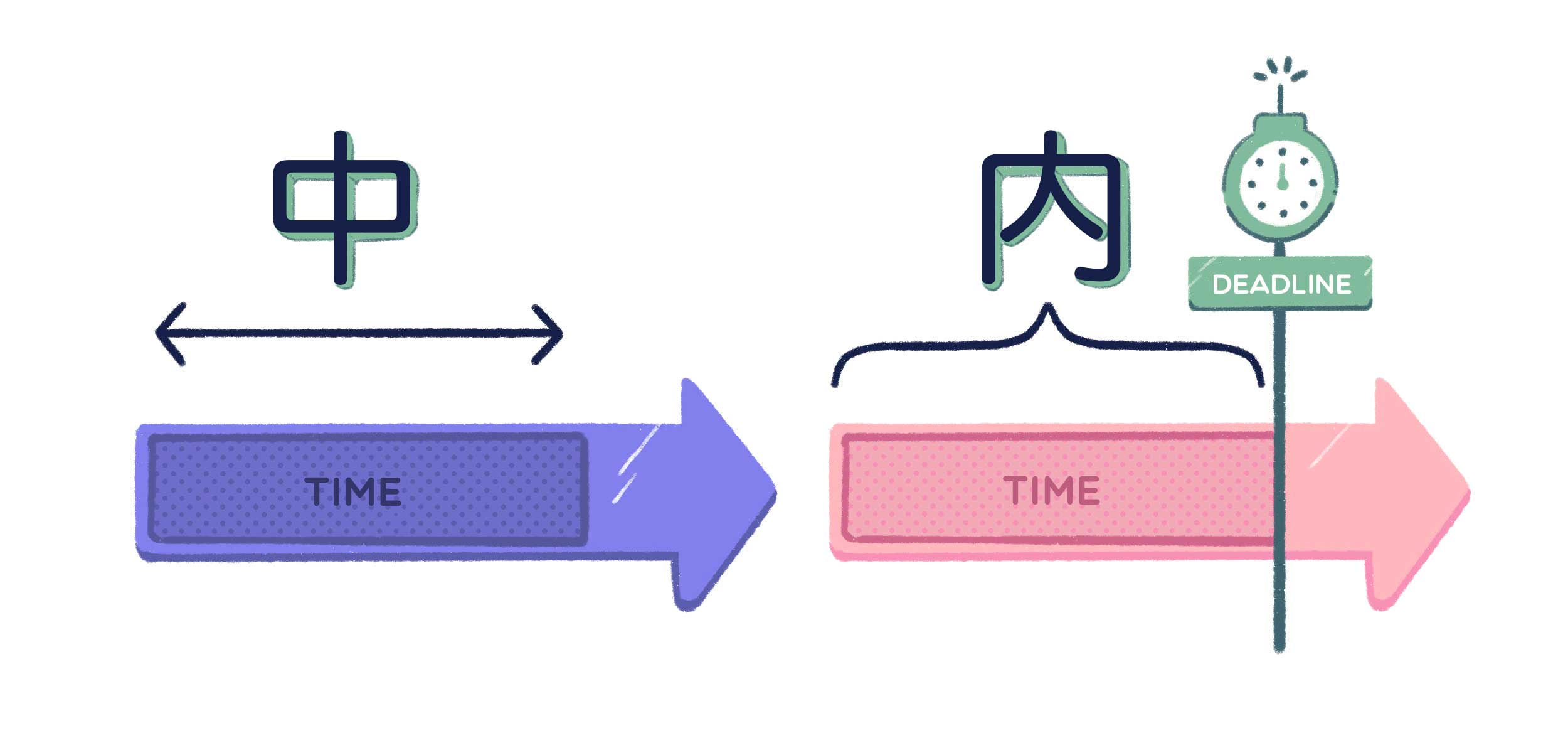

A little confusing? Hopefully the following image will help!

In this image, the arrows represent the flow of time, and the dotted part represents a period of time. It could be any period of time, but in the example we just used, the dotted area represents this year, and the part after the line is next year.

Just like the physical space uses, 内 highlights the boundary between "inside this year" (before this year is over) and "outside this year" (a future time - since we can’t go back in time!). Thus, the right image has a distinct "deadline" that marks the end of one year transitioning to the next year. 内 refers to the period before "the deadline," so "by the end of this year" is a typical way to translate 今年の内, as in:

- 今年の内に漢字を1000個 覚える!

- I’ll remember 1000 kanji by the end of this year!

中, on the other hand, is simply referring to the "location" in time of an event or an action, without any implied contrast with a future time. Because of this, you'd use 中 to say "this year" as in "during this year," "anytime this year," or "over the course of this year," for example:

- 今年中に漢字を1000個 覚える!

- I’ll remember 1000 kanji this year!

As we hinted at earlier, though, depending on context 今年中に can also mean "by the end of this year." This is usually if you are nearing the end of the year, because, just like in English, if you say the example above in mid-December, the implication is that the deadline is the end of the year.

So the above two sentences can have very similar meanings and even native speakers may not be aware of the difference between the two. However, knowing these nuance differences is important, especially when 中 and 内 are not interchangeable, as we'll see.

For example, to say "all year round," or "at any time of year," you'd attach 中 to 一年 (one year), as in 一年中.

- この国は一年中あたたかい。

- This country is warm all year round.

In this example, you cannot use 内 because the emphasis on the end point of one year doesn’t make sense when referring to anytime of year. It has to be 一年中, or its shorter and more formal version 年中.

In the same way, to say you are in the middle of doing something, you'd use 中 and not 内. Imagine you receive a call from your friend, but you are busy eating breakfast at that moment. In this case, you may say:

- ⭕ ごめん、今、食事中なんだよね。

❌ ごめん、今、食事内なんだよね。 - Sorry, I’m in the middle of a meal right now.

This is because when you are in the middle of an activity, you are somewhere in between the start and the end point of your activity. Since you are simply referring to the activity and not highlighting the time period, or contrasting it with a future period, 中 is your choice in this use.

Next, let's say your friend asks you to call them back as soon as possible. Your friend isn't usually this demanding, so you ask them why, and they explain that they need to tell you something before the end of the morning.

- ❌ 朝の中に話したいことがあるんだよ。

⭕ 朝の内に話したいことがあるんだよ。 - I have something to tell you this morning.

In this case, the choice is 内 because your friend’s focus is on the end of a certain time period. It emphasizes that your friend has something to tell you before the morning is over.

Your friend sounded very serious, so you promised to call them back as soon as you finished your meal. However, once you've you eaten your breakfast, you decide to go to the bathroom first before calling back as you suspect this could be a long talk. You think to yourself:

- ❌ 今の中にトイレに行っておこう。

⭕ 今の内にトイレに行っておこう。 - I should go to the bathroom now.

With 今, you can only use 内 because your focus is on the point where the situation changes. 内 adds the nuance that now is the opportunity to go to the bathroom before the potentially long call. Without this nuance, it doesn't make sense to talk about "inside now" in Japanese, so we'd never say 今の中.

You keep the promise and call back your friend as soon as possible. As your friend hoped, the call was successfully made in the morning. To describe the situation, you can say:

- ⭕ 午前中に電話で話した。

⭕ 午前の内に電話で話した。 - We talked on the phone in the morning.

The example earlier with 朝 used 内, and 中 wasn't possible. However, with 午前, another word for "morning," you can use either 中 or 内.

This is because, while 朝 means morning in general, 午前 refers to times of day between midnight and noon, like a.m. in English. The beginning and end points of 朝 are not clear cut, but 午前 starts at midnight and ends at noon. So 中 can be used with 午前, as a compound word 午前中, to neutrally say something happened in that period in time. If you use 内, as in 午前の内, it adds more nuance that you did it before the time changed from 午前 to 午後 (p.m.).

One last note that is a little advanced, but you don’t normally use 中 with 午後, as in 午後中. This is because 午後 can be divided up into more parts, such as afternoon, evening and night. When using 中, it can refer to any time all the way up to the midnight and it’s confusing which part of 午後 you are talking about, so you don’t really say 午後中. Just in case you're wondering how you would say "in the afternoon," that'd simply be 午後に, without 中, and most people would assume you mean sometime between the noon and the evening in that case.

Lots More Words In Real Life!

We are coming to the end of our exploration of 中 and 内. Hopefully you were able to grasp the basic concepts of these two words, and are now coming away with a better feel for how these two words are used in the real world.

To wrap it up, 中 neutrally refers to the middle, medium, or central position or part, while 内 refers to an inside that is surrounded by an outside, highlighting the boundary between the inside and the outside.

中 and 内 are very common words and we didn’t cover all of their uses in this article, so you’ll still run into new usages in the wild. Before you forget what you learned here, or 忘れない内に, please try to remember the 中 and 内 uses you’ve encountered before, and consider why each was chosen. And of course, keep an eye out for these words as you read and listen to Japanese. It will help consolidate your idea of the two words, and you’ll be better equipped for the new uses awaiting you!

-

The word pair 車内 and 車外 can also be used to refer to the inside and outside of a vehicle, such as a car and a bus. ↩

-

Although the translation of 中 and 内 in this example is "in," neither 中 nor 内 is the direct equivalent of the English word "in." Like if you live in Tokyo, you wouldn’t say 東京の中に住んでいます but just say 東京に住んでいます. Adding 中 or 内 is more for clarification, like you’d like to put the emphasis on the position or highlight the area within a certain surrounding. ↩

-

町中 can also be read as まちなか, and it has a different meaning than inside the town. This word rather means "in the middle of the town," or "downtown," so it’s basically used to point to a specific area within the town. ↩

-

It was mentioned earlier that the standalone use of 内 often adds a poetic or literary feel, but it’s not the case when it refers to a time period. In fact, when 中 and 内 are used for time periods, 中 tends to be combined to make jukugo words, such as 今年中, while 内 is commonly used alone, in the form of 〜の内 or its kana version 〜のうち. ↩