Brave Kobun pupils! I'm going to take you further into the woods of Classical Japanese with verbs. Remember, Kobun is very different from Modern Japanese, and, as such, you'll see new and unfamiliar features. In starting with verbs, I'm being biased and deliberate. It's my opinion that verbs are top priority in a Kobun education because:

- Classical Japanese, like Modern, can omit the subject.

- Again like Modern, adjectives work like light verbs.

- Verbs take longer to look up and identify accurately than nouns, particles, etc.

Seriously – it's a long process to decode verbs. I'll describe an approach each for the short-term and long-term Kobun students. Both approaches involve puzzling a verb's meaning by 1) establishing what kind of verb you're dealing with and 2) looking at what shape it's in.

The Short-term Approach

If you've never used Rikaichan/kun, check it out. Rikaichan is an app that doles out meaning and readings for unfamiliar Japanese words and kanji if you hover your mouse over in-browser text. The short-term approach to Kobun verbs is equivalent to using Rikaichan on a news article: unless you're really pro at Japanese, you won't mentally store all the new words and characters Rikaichan breaks down for you, but you can read and comprehend the news article. This kind of approach is about understanding a text you have time to sit with but don't expect to quote or write commentary about.

Let's start with this line, the first in Taketori Monogatari:

いまは昔、竹取の翁といふもの有りけり。

Here's the non-verb stuff in the sentence :

- いまはmukashi 昔: now (subject) an ancient time

- taketori 竹取: bamboo-lumberjack (AKA "bamboo wood-cutter")

- のokina 翁といふもの: an old man.

といふもの is technically a verb phrase. I'm ignoring it because it has carried on into modern Japanese as というもの. That leaves just one verb phrase to decypher: a 有りけり.

Given this information, I want you to spend a moment searching around in a kogo-jiten for what you think 有りけり means. Don't look up translations. Honestly look to see if you can analyze 有りけり the way you could "食べました", which is ["eat" + past + polite + affirmative + end of a sentence]. Did you give it your best shot? I hope so. Here's what I do:

Step 1: ID the Verb

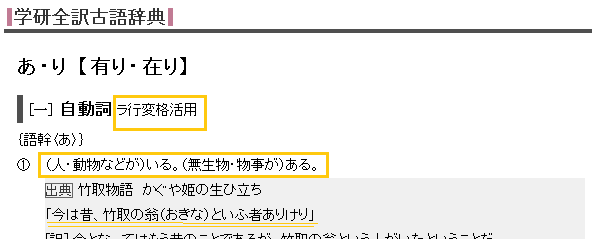

First, we'll need to figure out what kind of verb we're looking at. Find the verb in a kogo-jiten. 「有りけり」 as a whole doesn't get results. However, breaking it up into「有り」and 「けり」gives us results. Here's 有り.

The top orange box outlines the verb type: 有り is a ra-gyou henkaku ("ra-sound irregular") verb. The second box encapsulates the most common meaning: "to exist", "to be", etc. But wait — do you see the sample usage they provide? I've underlined it: it's the sentence we're trying to translate! We've definitely ID'd the right 有り. As for けり…

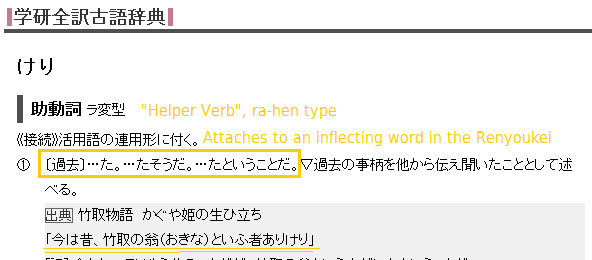

In the previous search, we could tell that what we'd found was a verb because jidoushi 自動詞 (transitive verb) was written before ラ行変格 (the verb type). But here the Kogo-jiten entry lists けり as 「jodoushi 助動詞」, which means "helper verb". Jodoushi won't appear on their own but, instead, always connect to something else.

The orange box in the screencap outlines that this 助動詞 is used to create a past tense verb. So, this けり is like the "-ed" in English "highlighted" and the "た" in Modern Japanese "食べた". Again, underlined in orange, the example provided is the very sentence we're translating! For other verbs, though, you won't be as lucky.

Pretend the sentence they provided wasn't the exact one we're looking at now. Two other search results appeared for "けり": one is a verb (not a helper verb) that means "to come along" and the other is a verb for "to be wearing". How do you know which is the right one? Mostly from meaning and context. While it's definitely possible to see verbs chained together, "live" (verb) + "past tense" (helper verb) makes more sense here than "live" + "came along/comes along"or "live" + is "wearing", especially after looking at the next step.

Step 2: Listen to the Verb

The next step: identify what form, or kei 形 the verb is in. I've translated another part of the entry for けり in that screencap: "Attaches to an inflecting word in the Renyoukei". If this けり attaches to a Renyoukei verb, we need to check if 有り is in the Renyoukei or not. Then we'll know for sure which of the three けり's is in this sentence. Ugh, homophones.

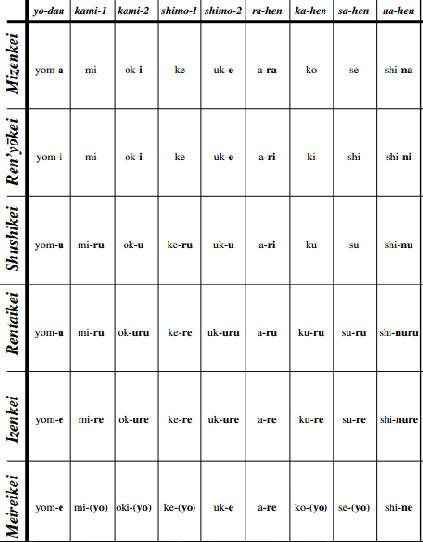

To check which "form" the verb is in (Renyoukei, etc.), think about the last sound in 「有り」 and check this chart:

This chart was made by Anthony Stewart. The original chart has more cool things and is available here.

Using the charts is like playing Battleship. The verb types are the x-axis points which intersect with sound-based forms on the y-axis. As the chart lists, 有り, a ラ行変格 verb, could appear as -あら, -あり, -ある, or -あれ. The form in our sentence ends in -り, which means we either have the Renyoukei or the Shuushikei.

Renyoukei is a connective form, like the Modern Japanese pre-masu stem. Shuushikei is a form that marks the end of a sentence, like how "-ました" in modern Japanese always comes at the end of a sentence and never in the middle. 有り doesn't end the sentence, so it's not in the Shuushikei. Plus, 有り is connected to something, which means it's the Renyoukei 「あり」. We were right with our context judgement: the right けり is the past tense helper verb. けり also happens to be in the Shuushikei, the sentence-ending form, so all the pieces line up.

It's helpful to know what all of those y-axis forms mean. But an in-depth knowledge of those verb forms isn't necessary in the short-term approach since you can just look them up.

If you put the pieces together ["live" or "exist" + past tense + end of sentence], it becomes clear what 有りけり as a whole means. Kafka-fuura skillfully translates this sentence as: "In a time now long past, there was an old man who was a bamboo cutter."

You might be getting curious about some patterns. Could 有り sit on its own in the Renyoukei? While using the short-term approach, don't fill your head with such stuff. Just look things up until they make sense. Eventually, some patterns will settle in your memory, and that's great, but memorizing patterns isn't the aim. The aim is to give you a process for sporadic Kobun dealings. That said, the short-term approach only works if you have time to sit with a Classical sentence and some dictionaries and charts.

The Long-term Approach

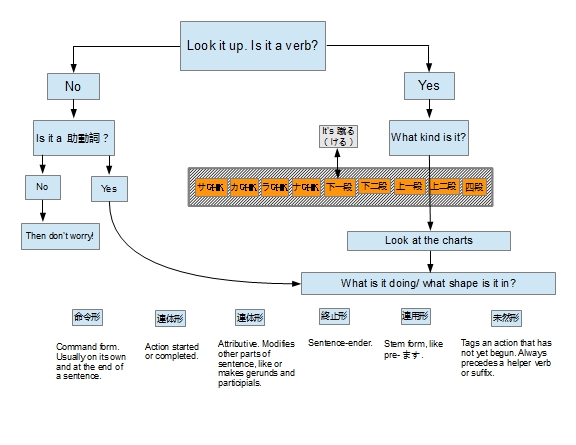

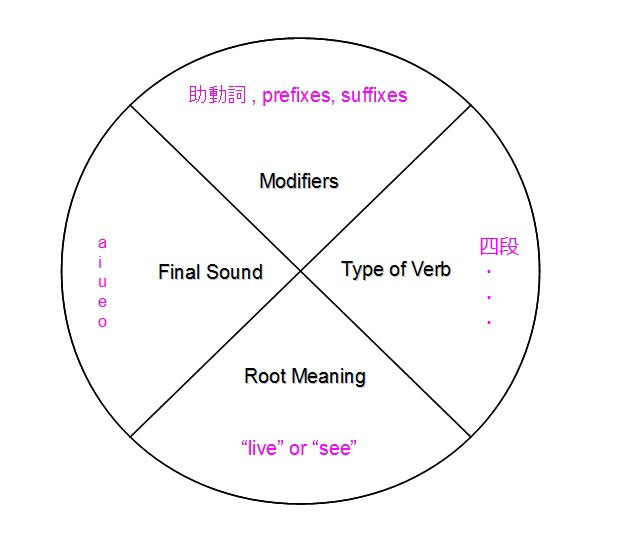

The short term method will hold back folks who really want to learn the lingo of the ancients. So, I've made the above flow chart for your referencing pleasure. Short-term and long-term students can benefit from the chart, but long-term learners should know it thoroughly.

To read more than the first couple pages of one Classical Japanese text, it's more efficient to have verb types steadily memorized on the front end of your learning journey.

Actually, that's how my Latin education was; we learned verb conjugations and noun declensions while reading increasingly difficult sentences at a slow pace. At first I was reading "In the picture is a Roman girl named Flavia", but by the end of the year, I could eek out a paragraph from the eloquent Cicero. If I had had a prior knowledge of Italian, my reading comprehension probably wouldn't have taken me a year, though, because of common vocabulary and roots. So if you have a functional grasp of modern Japanese (and motivation!), it won't take you a year to teach yourself what's necessary to read Kobun.

Step 1: Know Thine Verb Types

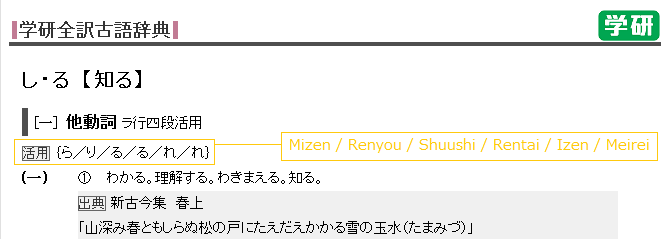

As I briefly pointed out earlier, Kobun verbs come in different types. Think of them as flavors. Things that are watermelon flavored just get called some variety of "watermelon-flavored", right? Verb type names aren't misleading. For example, yo-dan 四段 verbs are called "quadrigrade" because they conjugate into four different vowel endings. 知る is a 四段 verb, and conjugates as outlined in orange:

The vowels あ、い、う、and え added together make four grades of sound, see? Hence 四 (four) 段 (grades or steps).

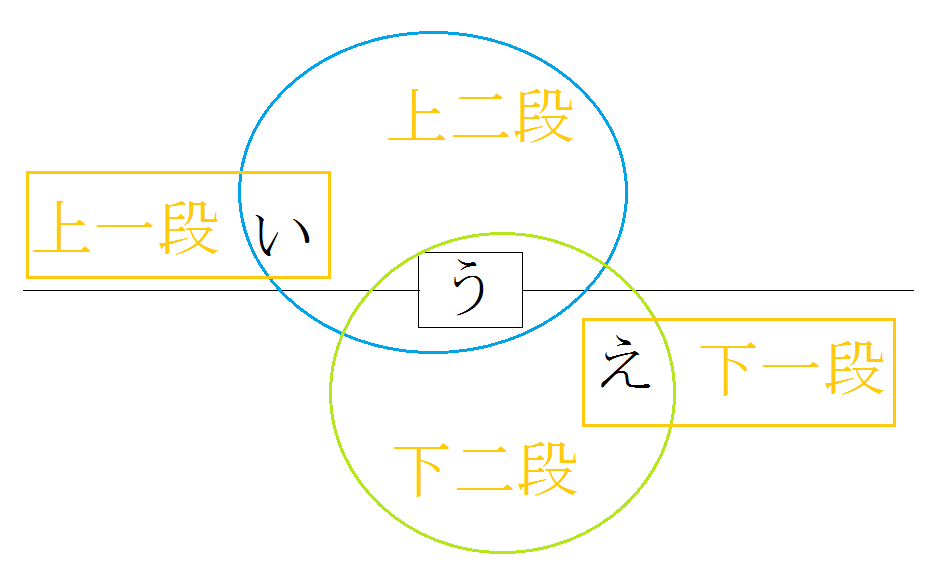

The other eight verb types are: kami-ichidan 上一段, kami-nidan 上二段, shimo-ichidan 下一段, shimo-nidan 下二段, and the irregular na-gyou henkaku ナ行変格, ra-gyou henkaku ラ行変格, ka-gyou henkaku カ行変格, and sa-gyou henkaku サ行変格 verbs. For the first four, see the next image. The last four conjugate mostly as 四段 verbs, but with irregularities you can reference in a traditional chart.

My favorite author on Classical Japanese, Vovin, actually boils those verb categories down to just three: verbs with a vowel stuck at the end of the root (like mi-, "see"), verbs stuck with a consonant at the end (shin-, "die), and irregular verbs.

Step 2: Know Thy Charts

There are a variety of charts out there, but they're all basically the same x/y-axis combo between verb types and forms. Hard-core classicists probably have, either intentionally or over time, memorized which sounds correspond to which verb forms.

Personally, I don't think you need to have the sounds memorized. It would suffice to just be really familiar with the form boxes and what they represent:

- Mizenkei 未然形: Imperfective, but not really, since it usually tags an action that has not yet begun. Connects often to form the negative.

- Renyoukei 連用形: Stem form, like pre-ます.

- Shuushikei 終止形: Sentence ender.

- Rentaikei 連体形: Attributive. Modifies other parts of sentence, like 「かかる人…」, "such a person…". Can also make gerunds and participials. Sometimes, this ends a sentence.

- Izenkei 已然形: Perfective. Action started or completed.

- Meireikei 命令形: Command form. Usually on its own and at the end of a sentence.

These forms are what I'm personally trying to memorize and understand, especially since I am now noticing Kobun forms in Japanese media a lot more. It's easy for me to notice and remember things like "けり", but not as easy to translate, say, a folk song as I hear it.

All Roads Lead to Rome

No matter which interest group you fall in for Classical Japanese, both translation approaches I've described emphasize looking at these four parts of verbs:

If you wish I'd provided more examples, check out the cool stuff below — especially the source with quizzes. Deciphering Kobun is a strategic process that takes practice (and time) to get right. If you have any questions, please say something on Twitter. The sources I've been using are have more fun tidbits than I have space in this article to fully explore (after all, they are books on the subject). Ditto for comments or criticisms: I want to hear your take on Kobun verbs, especially if you are learning it in class or on your own!