Finally, you can translate The Tale of Genji from the original! But can you read it out loud without confusing your Japanese-speaking friends? It would be strange, after all, if you didn't read「今日」 as「 きょう」, despite the fact that it was spelled as「けふ」in older texts.

If the けふ > きょう reading doesn't make sense, consider that languages change. Important sounds change, but writing takes a while to catch up to the new sounds, or sometimes it never does. You know these transformations occur because I just spelled the word "know" with a 'k', yet there's no 'k' in its pronunciation. There used to be! A long, long time ago.

In this post, I'll focus on two important sides of the same coin, which you'll use to purchase meaning in the Classics:

- How to phonetically read Classical Japanese kana, and

- How this knowledge helps you decipher Kobun texts

In Japanese, this system of sound conversion is called Rekishi-tekina kanadzukai 歴史的な仮名遣い, or "historical kana usage". I'll assume you've read the other Kobun posts (intro, verbs, jodoushi, adjectives, and honorifics), but even if you haven't, you'll learn cool skills, like how to read old-timey hiragana signs in Japanese.

English Mirror

Before you can use Old Kana rules, you need to know why they're beneficial. By looking at more familiar English — specifically, Middle English — you'll see why.

Read the stanza below from William Langland's "Piers Plowman" (from the 1300's). If you're strict with your "suspension of disbelief", this could ruin certain time travel movies for you; I don't remember Timeline characters having babel fish or translator microbes, and the script didn't sound like this:

"In a somer seson, whan softe was the sonne

I shoop me into shroudes as I a sheep were

In habite as an heremite unholy of werkes

Wente wide in this world wondres to here…" (Langland)

You can listen to that stanza, read with accurate Middle English sounds in this video:

Here's my interpretation just based on reading and listening:

In a summer season, when soft was the sun

I shop(?) me into shrouds as I a sheep(?) were

In habit as a hermit, unholy of works

Went wide in this world wonders to here

The question marks are beside words I couldn't make sense of, but made a stab at based on my Modern English. Want to see how close I got to a reasonable translation?

"In a summer season when soft was the sun,

I clothed myself in a cloak as I shepherd were,

Habit like a hermit's unholy in works,

And went wide in the world wonders to hear" (Attwater)

Notice the words that don't resemble our modern vocabulary. This exercise should give you a taste of the comprehension scale a Japanese native speaker approaches their own Classics with. historical kana usage rules help you do to Kobun texts what I did to the "Piers Plowman" stanza. In other words, you'll be reading funny Kobun spellings, filling it in with your Modern Japanese knowledge, and coming to quicker conclusions about the Classical texts you read.

Kobun Rules

Don't let the word 'rules' scare you. These aren't rules for you to follow; they're rules the sounds have followed, leaving a trail of bread crumbs from, say, an old ふ in the Kobun word 給ふ to an う in the Modern 給う.

Unfamiliar Faces

ゐ/ヰ and ゑ/ヱ are characters that are not used in Modern Japanese (except to invoke Shakespearean, old-timey language), but they crop up in the Classics. The hiragana ゐ and katakana ヰ represented the sound 'wi' but the words written with ゐ/ヰ evolved simply into an い (look back at the Piers Plowman video; English 'hear' used to sound way different, and was spelled differently, too).

The same is true for ゑ/ヱ, which used to be 'ye' (or even 'we'), and is responsible for "Ebisu" sometimes being romanized as "Yebisu".

If you would read ゑ/ヱ as え, you could discern what a Classic story is talking about based on your Modern Japanese vocabulary. For example, what comes to mind if you read こゑ below as "koe"? Let me help with the other vocabulary; gion-shouja 祇園精舎 is a temple name, and kane 鐘 means "bell".

「祇園精舎の鐘のこゑ」

Probably, you thought of the most common "koe" you hear in Japanese, and that's "voice". "Voice of the Gion Temple Bell"? Close enough; koe had a few other meanings, including neiro 音色, the quality, or "color," of a sound. So it's a metaphorical sense of 'voice' in that clause.

If you had read こゑ as "koye" instead of "koe", you might have missed this clue and had to go searching through a Kogo-jiten. We do that enough already, so you can see how sound rules make the process faster and easier.

Magic Particles

Moving away from unamiliar characters, を is a kana you know best as the direct object marker in Modern Japanese. But in Kobun texts, this was common in many other places where the 'o' sound could appear, mostly at the beginning of a word. In the Nara period, the pronunciations of を and お were consistent and starkly different (wo and o). But the を pronunciation began wobbling in the Heian period. Here's an example of the Kobun を acting unexpectedly:

「を と兄(いろせ)といづれか愛(は)しき」(From the Kojiki)

That を? It's actually 「男」- "boy / man", which could also be hiragana'd in the slightly more familiar 「をとこ」way, but also as 「をのこ」. You just need to read these を's as お.

Also, you learned at the beginning of your Japanese education that は (wa) and へ (e) aren't pronounced the way they're written, so you've already been using modern pronunciation for tricky, archiac spellings!

Small Things

This Kobun rule of thumb will help you with words like しずか ("quiet") and 味味 ("flavor"):

Read づ as ず and ぢ as じ.

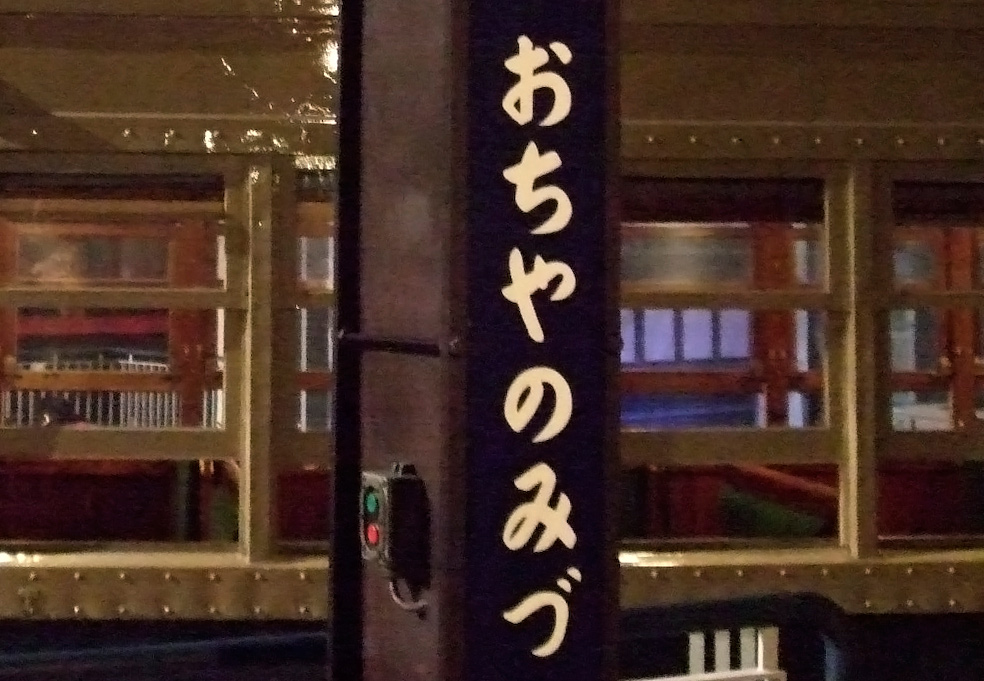

There are a lot of words that have changed their spelling in this way, like 水 (みづ → みず), 何れ (いづれ → いずれ), 閉(と)ぢる → とじる, and 紅葉 (もみぢ → もみじ).

If you look at the photo above, you can see that this train station post has on the side the location: Ochanomizu. Yet, the hiragana is "Ochiyanomidzu." I described the づ → ず rule, but it's also worth mentioning that small characters weren't really a thing way back when; hence, おちゃ is written as おちや. Little y-sounds (や、ゆ、よ) and small つ's (such as in あった) will often be rendered as the standard-sized hiragana in Kobun texts, so try sounding things each way for clues.

Tenko, or stage directions

Below you'll find bulleted lists of Tenko -"change of call". These have to be practiced and memorized, but the bright side is that they're straight-forward.

On the left is a Kobun word, and the sound change formula you should remember is on the right of the semicolon. In the formula, the left is the Kobun kana, while the right is how you read it:

- かは (かわ);ha → wa

- ひたひ (ひたい);hi → i

- たまふ (たまう);hu → u

- まへ (まえ);he → e

- おほす (おおす);ho → o

- らむ (らん); mu → n

The Tenko rules above are for the middle of words, so 我 is still "ware", and 昔 still "mukashi."

These are the other Tenko trends:

- くわかく (かかく);kuwa /guwa → ka, ga

- あふぎ>扇 (おうぎ);a + u → ō; verbs with the a + u vowel ending are an exception (like 給ふ, read as 給う in modern)

- じふじ> 十時 (じゅうじ);iu → yuu

- けふ > 今日 (きょう);eu → yō

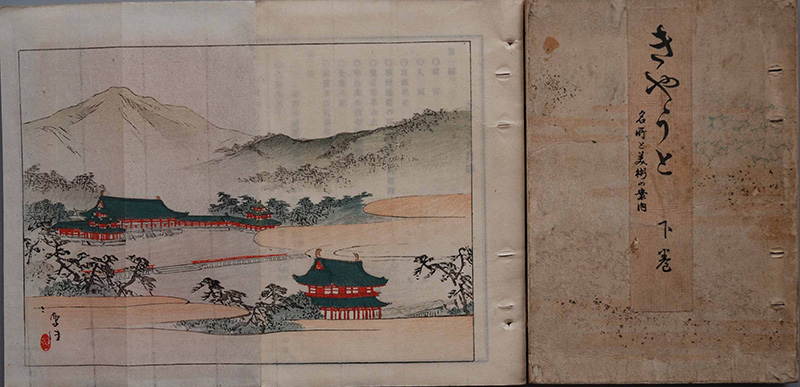

- きやうだい>兄弟 (きょうだい);iya → yō(pronounce the Kobun hiragana for that word; it's almost like a southern accent)

Sound rules make the song below pretty interesting. The original melody uses modern Japanese lyrics, but the musical group likes to make Kobun-esque cover songs. In doing so, koe 声 became archaic "koye", but the jodoushi らむ is still pronounced らん.

Conclusion

Nobody was born knowing the English alphabet; someone taught you how letters represent sounds. Think back to that learning process. Rules like 'i' before 'e' except after 'c' are inaccurate but often helpful. The Japanese sound rules for historical kana usage aren't accurate 100% of the time, either, but they should make Kobun a little less confusing and empower you on any quest to better understand the Japanese language.