What do dinosaurs, outdated fashions, and SNL have in common? They're going to help us with Classical Japanese. Today's course in your Kobun education is easy breezy: Jodoushi 助動詞. They're "helper" or auxiliary verbs. I mentioned these critters a little in my last article on Kobun but I'd recommend you read Part 1 (the introduction to kobun) first if you haven't already.

Kobun jodoushi are pretty old (we are talking about classical Japanese, after all!), but they do still show up in modern Japanese from time to time. We'll see them fixed with verbs, in set phrases, or even adverbs. Some exist as useable grammar points. Most, however, appear in much the way that everything else in Kobun does: in the monogatari's and nikki's and other classical Japanese texts. That is, after all, why we're learning so much about Kobun!

Timeless Jodoushi

Somehow, these dinosaurs made it into Modern Japanese, but they often sound formal or eloquent. Like, "Asteroid scientist, I am Danneth of Sharpteeth Abbey. You know the whereabouts of the asteroid which vanquished my ancestors. Kindly take me to it, or kindly prepare yourself for death", kind of eloquent. Not so old-timey sounding, but definitely eloquent.

For each jodoushi below, I've provided a Kobun sentence taken from my favorite online Kogo-jiten where that jodoushi makes an appearance.

べし

べし was the base form of a jodoushi that has survived through two evolutionary tracks to the Modern: べき (the old Rentaikei) and べく (the old Mizenkei and Renyoukei). べき is used these days to talk about the way things ought to be done, like English "should", and doesn't sound particularly high-brow or anything like the rest of these. べく is less common, and is a conjunction that indicates a direct cause or prerequisite. But in Kobun, べし could also mean that someone is assuming or framing a situation a certain way.

Kobun:「人は、形・有り様のすぐれたらんこそ、あらまほしかるべけれ」(From Tsurezuregusa

Modern: 人間は 容貌や 風采がすぐれていることこそ、望ましいだろう。

English: "It is desirable that a man's face and figure be of excelling beauty" (Keene 3-4).

ず

In both Modern Japanese and in Kobun, ず is a negative, like "not". In Modern, ず can sound pretty formal. The ず jodoushi is ぬ in the Rentaikei (see part 2 of this series, scroll down to step 2), and that form appears in Modern as well, though less frequently. There's important nuance to the ぬ breed of negation, so ask around before using it or you might sound like a better-than-thou snob (or, in Mami's words, "a bossy Shogun"). In Kobun, however, ず/ぬ is a frequent (non-snobbish) -ない kind of negation.

Kobun:「京には見えぬ鳥なれば、みな人見知らず」(From Ise Monogatari

Modern: 都では見かけない鳥であるので、そこにいる人は皆、よく知らない。

English: "Since it was of a [bird] species unknown in the capital, none of them could identify it" (Tales of Ise 76).

ごとし

I've only run into ごとし once in Contemporary Japanese literature (as ごとく), if that tells you anything about its frequency. ごとく is a sophisticated-sounding ~のようだ, in Modern Japanese. The Kobun ごとし, however, could mean a variety of things. Like the modern version, it could be used for comparison, but also for equivalence or as an example-provision:

Kobun:「世の中にある人とすみかと、またかくのごとし」(From Houjouki

Modern: 世の中にいる人間と住居と(が無常なこと)は、また、これと似ている。

English: "In this world, people and their dwelling places are like that, always changing" (from here).

る、 さす、and す

Yeah, I know, there's -る in almost every verb garden out there. This one is pretending to be a Kobun weed when really it's the base form of almost the same passive or potential you'd recognize today. The others – さす、しむ、 and す – are causative, which also kind of overlap with modern. Go here for a more detailed breakdown of them.

Kobun:「涙のこぼるるに、目も見えず、物も言はれず」(From Ise Monogatari)

Modern: 涙があふれ出て、目も見えず、物も言うこともできない。

English: "I am blind and speechless with tears" (Tales of Ise 110).

Debbie Downer Jodoushi

These Jodoushi are negatives. When Classical writers saw an affirmative verb's bridge of dreams and wanted to crush it, they used one of these bad boys. What's that, Taketori Monogatari? Bamboo cutter "有りけり"? NOPE. Author guy's Pokémon Pen slams the sentence with "有らぬ" and there wasn't an old bamboo cutter.

まじ

Do you remember this advertisement from the very first part of the Kobun series?

Written there you can see maji、which negates "forgive" and generally seasons the sentence with some negative feelings:

Kobun-ized ad: 許すまじ!

Modern: 許すな! or 許さないぞ!

English: Don't yield (to pollen)!

じ

This is pretty equivalent to the modern 「まい」. It's a negative + "probably" or negative + intention. See here:

Kobun:「京にはあらじ、あづまの方に住むべき国求めにとて行きけり」 (From Ise Monogatari)

Modern: 京には住むつもりはない、東国の方に住むのにふさわしい国を探し求めるためにと思って。

English: "Perhaps because he found it awkward to stay in the capital"… "[He] journeyed toward the east in search of a place to live" (Tales of Ise 74).

Yesterday's News

The following jodoushi relate to time. Most of them are for the past, but not all.

けり、き、and けむ

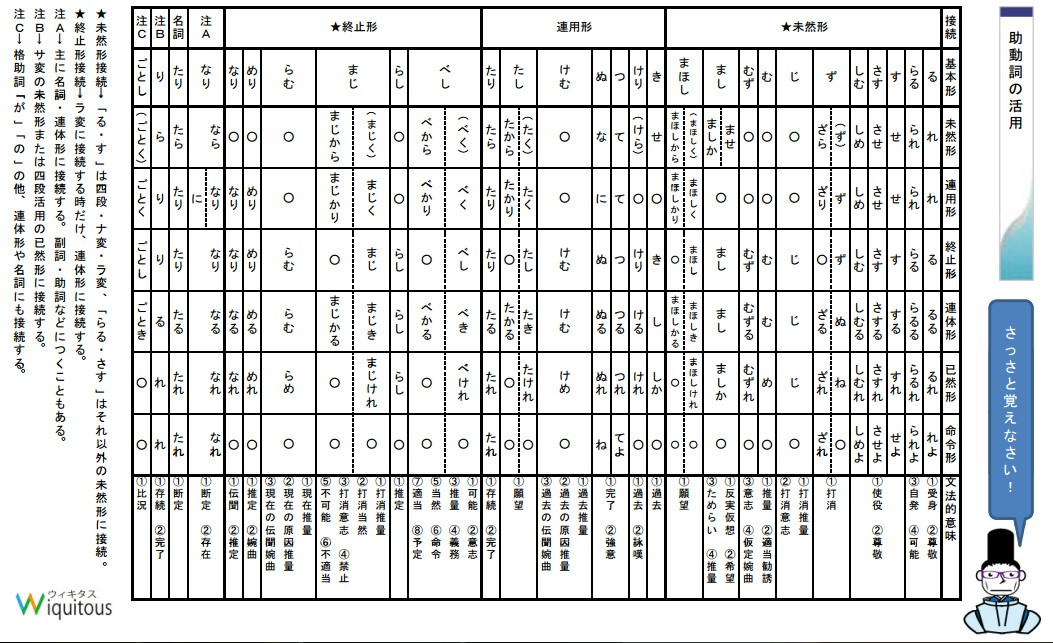

We encountered けり in the Kobun verbs article – it's a past tense thing. き is the same, but it has a crazy line of conjugation, so be sure to check out the chart I include at the end of this article. けむ、meanwhile, talks about something that has happened and is part conjecture (see the -ただろう in the sentence translation).

Kobun:「昔、こはたと言ひけむが孫といふ」(From Sarashina Nikki

Modern: 昔、こはたと言ったとかいう(人)の孫という。

English: "They said that they were the descendants of a [once-]famous singer called Kobata" (Doi and Omori 11).

らむ

Like in Disney's Mulan, when Mushu says, "Dishonor on you, dishonor on your cow…." This jodoushi casts "Deshou" on the situation, "deshou" on a reason for the situation, and general vagueness all around, in my opinion, since らむ can also equate to euphemism or simile.

Kobun:「などや苦しき目を見るらむ」(From Sarashina Nikki)

Modern: どうしてつらい目に遭うのだろうか。

English: How did it come to such a rough time as this? (my translation)

む/むず

This jodoushi can be the volitional (modern ~しよう!) or a "deshou". As in modern, a "deshou" or volitional can go a long way towards soft suggestions for the way things ought to be. Likewise, む/むず in Konbun could represent a suggestion and even, as with らむ, simile.

Kobun:「かのもとの国より、迎へに人々まうで 来むず」(From Taketori Monogatari)

Modern: あのもとの国 から、迎えに人々がやってまいるだろう。

English: "People are going to come from my original land for me" (Behr 128).

These jodoushi are flip-a-table, pull-the-plug, 800% done. Or, the verb they attach to sounds like a completed action, at least.

つ

The Renyoukei (see part 1 of this series and scroll to "step 2") for つ is て. Classical Japanese had a few other sentence parts (like particles) with 'て' at the border between words, so you'll want to list out some guesses when translating. In addition to completion, つ was written for lists (like "…たり…たり、…" in modern) or a "deshou"-tinted "certainly" or "without mistake" ("たしかに…だろう").

Kobun:「 蠅こそ、憎きもののうちに入れつべく」(From Makura no Soushi)

Modern: はえ(という虫)こそ、憎らしいものの中に確かに入れてしまいたいもので

English: "The fly should have been included in my list of hateful things . . ." (Morris 70).

ぬ

This is a different ぬ than the negative ず/ぬ. This ぬ is completion. How do you know which ぬ is being used in the sentence? You'll have to look at charts and forms. Remember that the Mizenkei usually precedes negatives, while the Renyoukei is usually used as a connective form. So verb in Mizenkei + ぬ = negative action, while Renyoukei + ぬ = completed action (probably). There's more to it than that, but here's an example sentence to get you started – it's a beautiful poem from the Kokin Wakashuu, as translated by Kuma Papa-san).

Kobun: 「散りぬとも香をだに残せ梅の花」

Modern: 散ってしまっても香りだけは残していってくれ、梅の花よ

English: "If these plum blossoms must wither/scatter, at the very least leave your fragrance. . .." (Kafka-Fuura).

り

This jodoushi can signify either completion or an on-going action – use your best judgement when translating.

Kobun:「くらもちの 皇子は 優曇華の花持ちて上り 給へり」 (From Taketori Monogatari)

Modern: くらもちの皇子は優曇華の花を持って都へお上りになった。

English: "Prince Kuramochi has returned with the Udonge flower!" (Behr 108-109).

The Wishlist

Ambrose Bierce, in The Devil's Dictionary, defines hope as "Desire and expectation rolled into one", which is exactly what kibou 希望 sounds like. Guess what these jodoushi express? Hopes, wishes, and dreams, like the modern -たい form.

たし and まほし

These are both like the modern -たい or (て)ほしい, depending on the subjects and objects in the sentence.

Kobun:「帰りたければ、ひとりつい立ちて行きけり」(From Tsurezuregusa)

Modern: 帰りたいときはいつでも、(自分)一人ふいと立って行ってしまった。

English: "When he was ready to go home, he at once got up and went off all alone" (Porter 53-54).

The Circus Group

The final group of jodoushi are a hodgepodge mix. Some resemble verbs, while some simply have unique meaning or classification.

なり

This jodoushi only sounds like the regular verb "なり" by coincidence. なり tags onto a verb to convey an assumption of some sort, hearsay, or to point out that something has been physically heard, as in:

Kobun:「 音羽山 今朝越えくればほととぎす 梢はるかに今ぞ鳴くなる」(From Kokin Wakashuu)

Modern: 音羽山を今朝越えて来ると、ほととぎすが梢はるかに今鳴いているのが聞こえるよ。

English: "Journeying onward over Otowa Mountain while the day is young, I hear a cuckoo singing high in the distant treetops" (Kokin Wakashu 41).

まし

まし is what's called a "counter-factual supposition". It's inherently hypothetical – sometimes just an observation, but sometimes conveying wistfulness. It often connects to the conditional ~ば, but it doesn't have to. "Would that I had eaten ice cream one last time before the zombie apocalypse began!" is an example in English.

Kobun: 「雪降れば木毎(ごと)に花ぞ咲きにけるいづれを梅と分きて折らまし」(From Kokin Wakashuu; more breakdown here)

Modern: 雪が降って、木に白い花が咲いたように見える。どの木を本当の梅の木と区別して折ったらよいだろうか。

English: "After the snowfall, flowers have burst into bloom on every tree. How am I to find the plum and break off a laden bough?" (Kokin Wakashu 81).

めり

Like a lot of things on this list, めり indicates a projection of circumstances, but, unlike most of the others, has a strong tinge of uncertainty or neutrality. In English, this would be the difference between "Someone forgot their bag" and "It looks as if someone forgot their bag".

Kobun: 「 簾少し上げて、花奉るめり」(From Genji Monogatari)

Modern:(尼君は)すだれを少し上げて、(仏に)花をお供えしているように見える。

English: "A nun, raising a curtain before Buddha, offered a garland of flowers on the alter" (Suematsu 92).

らし

The Kobun らし acts exactly like the Modern らしい, but I don't know that they are actually related (changing from a jodoushi to an adjective?). But like so many others on this list, らし is conjecture, a statement about the appearances of a situation or thing, including the reason something came to be.

Kobun:「ぬき乱る人こそあるらし」(From Kokin Wakashuu)

Modern: 糸を抜いて玉を乱れ散らす人がいるらしい。

English: "There must be a man unstringing them at the top" (McCullough 482).

らる

らる is classified on charts and in Kobun discourse as 自発. Spontaneous? As in "Spontaneous Combustion Man"? Yeah, I didn't get it either, at first. But if you reframe it as an expression of naturally occuring or unplanned actions and circumstances, then it makes more sense.

Kobun:「なほ梅の 匂ひにぞ、いにしへの事も立ちかへり恋しう思ひ出(い)でらるる」(From Tsurezuregusa)

Modern: やはり梅の香りによって、以前のことも(当時に)さかのぼって、自然となつかしく思い出される。

English: "It is the perfume of the plum which sends our thoughts lovingly back to the days of old" (Porter 21).

——

Wrap-up: A Kobun Jodoshi Chart

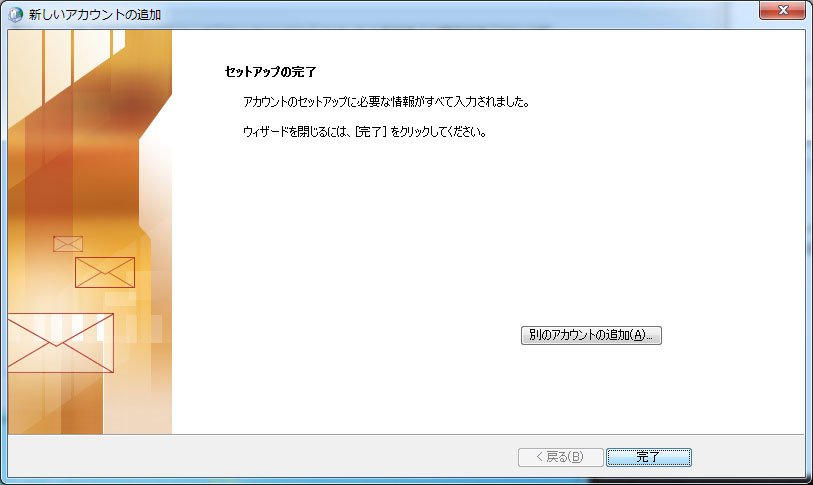

As promised, here is a jodoushi chart, made by the education site "Wiquitous". The top row is the verb form (Renyoukei, etc.) that the jodoushi tags onto, while the right side scales down the forms the jodoushi conjugate through. Empty circles mean that the jodoushi doesn't appear in that form. Meireikei (command form), for example, doesn't go hand-in-hand with many helper verbs, and that makes sense when you think about it.

Jodoushi were way easier than verbs, right? The verb patterns I talked about before permeate everything, so knowing the forms is truly essential. Hopefully, learning about helper verbs just made the previous lesson snap into focus. We're not completely done looking at conjugations, though, because adjectives are still to come.