Languages are always changing. The English that you and I speak today is almost completely different than that English people spoke a hundred years ago, and it’s even a little different than the English people spoke in the 90s. (Who says “tubular” anymore?) Japanese is the exact same way, but some people don’t really realize how much Japanese has changed.

Reform!

Why does language change? Some of it is a natural progression, with words and phrases going in and out of style, eventually becoming phased out of a language. But sometimes language is changed very deliberately and carefully. Probably the best example of this is the Academy of the Hebrew Language, located in Israel, which studies and regulates Hebrew. The Academy figures out how to fit new words and concepts like “Twitter” into the Hebrew language while staying true to tradition.

There isn’t really an organization in Japan equivalent to the Academy of the Hebrew Language, but over the years there have been efforts by the Japanese government to curate the Japanese language.

Post-War Changes

In 1946, right after WWII, the Japanese were open to all sorts of big change. Like, huge changes. Since most of Japan had been bombed into oblivion, the country was rebuilding literally from the ground up, and lots of people thought it was the perfect time to change Japanese society.

Some Japanese wanted to adopt another language altogether. Novelist Naoya Shiga thought French sounded good and wanted the Japanese to adopt it as Japan’s national language. Needless to say, people weren’t enthusiastic about it.

Lots of people were fine with Japanese, but wanted to streamline the language a bit more. The American Occupation wanted to eliminate kana altogether and make Japanese all romaji, which didn’t go over well (surprise!).

When the whole romaji thing didn’t pan out, the Occupation tried other ways to simplify Japanese. They attempted to cut down on the number of kanji in Japanese by creating a standardized list of kanji for everybody to learn. So yes, you can blame/thank the American Occupation for the Jouyou Kanij.

But it wasn’t just kanji that was changed after the war. Even hiragana, one of the most basic written elements of Japanese, was changed to what we know as gendai kanazukai (modern kana usage). I like to think of gendai kanazukai like a huge patch for the Japanese language with bug fixes and balance changes.

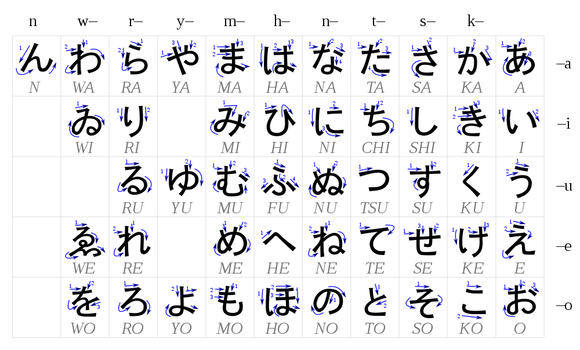

The Kana You Never Learned

As part of these language reforms, the Japanese cabinet removed both wi and we from official usage. The kana wi (ゐ in hiragana or ヰ in katakana) and we (ゑ in hiragana or ヱ in katakana) were once part of hiragana as much as あ or ん, but wi and we were phased out because, quite frankly, they weren’t really needed. You can make roughly the same sounds with ui (うぃ) and ue (うぇ), and by that time most people had pretty much abandoned wi and we anyway in favor of i and e.

Today, some people still use wi and we occasionally (just to be super cool and ironic, I’m sure), but you really won’t see them around too much. Both are very much on their way out of the Japanese language, and will soon be to the Japanese language what “ð” is to the English language.

Another change that was made with gendai kanazukai was yotsugana (四つ仮名), or “four characters.” Before gendai kanazukai, four characters (じ, ぢ, ず, and づ) had really confusing and different pronunciations. Nobody could agree on how to pronounce the characters. With gendai kanazukai, the yotsugana were given two official pronunciations: じ and ぢcan be pronounced as ji or zi, and ず and づ can be pronounced as zu.

But that’s not even mentioning the nicest change that came with gendai kanazukai. There didn’t used to be small kana, so if you saw a word like りよう, you’d basically just have to guess if it was pronounced riyou or ryou. Given, you could often guess from context, but anything that gives clarity can’t be bad, right? After gendai kanazukai, you have りよう for riyou and りょう for ryou.