Japanese has a ton of words that are borrowed from English, called loanwords. This can be a big help to native English speaker because it offers a wealth of built-in vocabulary. However deciphering the readings and pronunciation of this free vocabulary is another story. How many times have you read a long string of katakana, repeating it over and over before figuring out what English word it was supposed to be?

There is no magic formula that makes it possible to recognize those words instantaneously, but the changes that Japanese makes to English words do have some patterns that make sense. In this Guide we'll explain some of the main patterns and help you interpret the loanwords that are giving you trouble.

What's up with all those extra vowels?

Let me note before we get started that this Guide is not going to address the question of when/why certain consonants become doubled, because if we don't leave some things out it'll be the length of a PhD dissertation, and this phenomenon isn't one that most confuses the language learner.

Japanese syllable structure is more restricted than English in two important ways:

- There are only limited cases where two consonants can stand next to each other in Japanese. As you know, if you've read our guide to the Japanese past tense, these are certain sequences of two identical consonants, and certain sequences of ん and another consonant. In English, many sequences of two or three consonants are common that are impossible in Japanese.

- In English, pretty much any consonant can end a word, but in Japanese, only the nasal consonant ん can end a word.

This is why there are all kinds of extra vowels in those long katakana words.

When two consonants are together in English, a vowel is added to break them up to make it Japanese:

ski – スキイ sukii

fry – フライ furai

And when a consonant other than n ends a word, a vowel needs to be added after it:

bus – バス basu

beer – ビイル biiru

The result is that a one syllable word in English can become multisyllabic:

strike – ストライク sutoraiku

It's important to recognize that the number of sounds and the number of English letters isn't always the same. We could solve this problem by writing everything in phonetic transcription, but given that you already have to learn three writing systems to learn Japanese, I'm going to assume you don't want to learn yet another one to read this guide. So instead, wrap your mind around these points:

- Some added vowel letters in the Japanese words aren't actually added vowel sounds: in sutoraiku, ai is actually the same sound written by the single English letter i. That's pretty easy to deal with, though, since that's how you'd sound out ai in English pronunciation anyway.

- There are English words that use a single letter to represent a sequence of two consonants. "Taxi" has only one consonant letter in the middle, but that's actually two consonant sounds. The fact that we spell the two sounds (ks) as one symbol in some words does not fool the Japanese brain into being able to pronounce it, so a vowel has to be added:

taxi, actually pronounced "taksi" in English – タクシー takushii

- Of course, if the letter x is at the end of a word, two vowels will need to be added, because you can't end a word with the consonant s:

sex, actually ends in "ks," one vowel "sekus" or "seksu" is not enough , thus - セックス sekkusu

likewise, fax - ファックス fakkusu

There are also cases where the opposite happens and two-consonant sequences in English get interpreted as single consonants in Japanese. つ, which sounds like "tsu," is not two consonants in Japanese but is a fancy single consonant that linguistics nerds call an affricate. Since it's only one consonant, it doesn't need to have a vowel added.

There's variation in how this sequence is treated: Sometimes it will drop the "t" part, but other times it will be left alone. For example, although the first is more common, there are two pronunciations of pizza:

pizza – ピザ piza, ピッツァ pittsa

Since ts can act as the single consonant つ, often if a word ends in ts, it will add one vowel, but not two:

guts is ガッツ gattsu, not gattusu or gatusu

You'll see the same variation with voiced version づ which sounds like dzu. It usually drops the first half and becomes z instead, but you will also find it left intact:

goods – グッズ guzzu, グッヅ guddzu

This may have something to do with dialect variation. I'm told that in the Tokyo dialect these two spellings sound the same, and in other places they would be pronounced differently.

The only other situation where an English consonant sequence is left alone is if it's one of the few that is permitted in Japanese. English mostly doesn't have the sort of double consonants that Japanese has. We spell some things that way, but we don't really pronounce them as double, which is why it's one of those tricky things to get right in Japanese pronunciation. As you've seen in some of these examples, Japanese loves these so much that it actually adds them to some English words.

The other type of consonant sequence that's OK in Japanese is a nasal-consonant cluster that agrees in place of articulation. Basically, the result is:

panda remains panda in Japanese because n followed by d is A-OK

present has to add two vowels, but not a third – puresento, not puresenuto – because nt is OK.

But wait. Why isn't it always the same vowel?

In the previous section, you may have noticed that the added vowel is not always the same, even within the same word.

present – プレセント puresento

strike – ストライク sutoraiku

What's going on here is that the added vowel is usually u, but after t and d, o is added instead.

There's a reason for this. In Japanese, the sequence tu will always be pronounced tsu, and the sequence du will always be pronounced dzu. So adding o instead of u allows the word to retain the t or d of the original English word instead of being changed to ts or dz. Although the language does not do this on purpose to help us poor English learners of Japanese, we can be thankful that it does eliminate one source of possible confusion.

You will also see u added after sequences pronounced ts and dz in the original English:

goods – グッズ guzzu, グッヅ guddzu

guts – ガッツ gattsu

There are also a few common cases where you will see added i. Usually these are older loans, which may have i after word-final k, such as the following words which were both borrowed in the 19th century:

cake – ケーキ keeki

steak – ステーキ suteeki

You can actually see this contrast in the same word borrowed at different times with different senses: the word "strike" borrowed in the 19th century with the meaning "labor strike" is pronounced ストライキ sutoraiki, and the later loan with the meaning of a strike in baseball is ストライク sutoraiku.

Consonant Substitutions

As you also may know, adding sounds is not the only kind of change that occurs when an English word is borrowed. Sounds may also be changed or deleted, because the two languages don't have all the same consonants and vowels. In this section we'll look at some of the main things that happen to consonants.

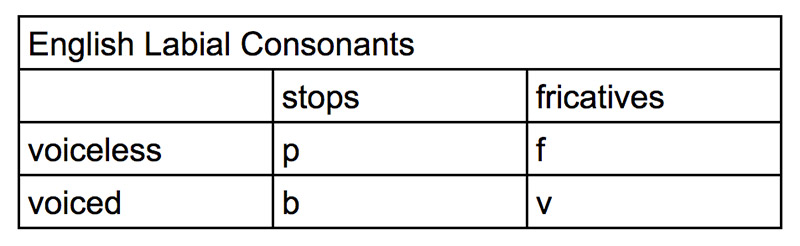

Labial Consonants

Labial consonants are made with the lips. In English we have more of these, so Japanese has to make some changes.

(Stops are consonants where the airflow is momentarily completely stopped; fricatives are ones you can extend in a hiss. Voiced consonants are made with vibration of the vocal cords – put a finger on your voicebox when saying v and you should feel a buzz.)

The f-sounds in Japanese and English are not identical. In English you touch your upper teeth to your lip and in Japanese you just use your lips. But they're close enough to be used to replace one another.

fan – ファン fan

film – フィルム firumu

But there's no voiced version in Japanese, so words with v take the next best thing, the voiced stop:

vanilla – バニラ banira

This replacement means that some words that are different in English may become the same in Japanese:

vase – ベース beesu

base – ベース beesu

Complementary Distribution

There's also one funny thing going on with the labial fricatives that we almost could ignore because it only happens in very old loans, but one of them is the most common word ever (at least when I talk), so I think it's worth an explanation: the borrowing of "coffee" as コーヒー kouhii .

When you learned the H line of your kana chart, you may have been taught one odd-man-out pronunciation:

ha hi fu he ho

The f in there is that not-quite f sound described above, to be specific. It used to be in the old days that f only appeared before u in Japanese, and h couldn't appear before u. This is what linguists call complementary distribution. One way to think of complementary distribution is Superman and Clark Kent. They're both the same person, but when sitting at a desk at the Daily Planet he's Clark Kent and when flying in the sky he's Superman. You never see Clark Kent leaping tall buildings in a single bound; you never see Superman writing a newspaper article. They're in complementary distribution: the same person, but they appear differently in different environments.

F/H in Japanese, at an earlier point in history, were like Clark Kent/Superman. They were different surface forms of the same consonant – that's why they are in the same kana line. Before most of the vowels, F/H sounded like h (Clark Kent) but before u, it was f (Superman).

This distribution still holds true in a lot of native Japanese words, but the wealth of borrowings over the years has made new pronunciations possible. So for instance we've got the word film that we saw above, borrowed as firumu with f before i. The katakana spelling フィ was adopted to represent this sequence.

But the word "coffee" was borrowed very early in the 17th century, a time when pronouncing f before i wasn't possible. So the f was treated as an instance of the magical transforming F/H. Before the i vowel, that magical consonant came out as h, and there's your コーヒー.

R and L

R and L in American English are both what are called alveolar liquids (the tongue touches the alveolar ridge, which is that ridge on the top of your mouth right behind your front teeth.) Japanese has only one consonant like this, but the old racist stereotype of the pronunciation"flied lice" is actually inaccurate, because the sound in question is not really like English L. In fact it's more like the way D is pronounced in the middle of a word like "rider" in American English: a quick flap against the alveolar ridge. So in fact both R and L are replaced with this different consonant, although the romaji spelling makes it look like only one of them changes.

rule – ルール ruuru

love hotel – ラブホテル rabuhoteru

rival – ライバル raibaru

By the way, ever wonder why purin is Japanese for pudding? So close but so far, right? But that's only if you're looking at the spelling. If you speak American English, say "pudding" and pay attention to the consonant in the middle. It's that quick-flap thing that's identical to what we're supposed to say when pronouncing the Japanese "R". So no wonder that's how it got spelled in Japanese.

R is commonly treated differently at the end of a syllable. It disappears and the vowel becomes long as a sort of compensation to keep the syllable the same length:

corner - コーナー koonaa

Interdentals

English has two fricatives that are not found in Japanese and in fact are pretty rare in the world's languages. We write them both as th, but there is a voiced and a voiceless one.

Here are examples and the symbol that linguists use to write them:

voiceless θ – thin

voiced ð – the

The closest sound in Japanese is substituted. These are the alveolar fricatives s and z.

voiceless θ:

marathon – マラソン marason

Ithaca – イサカ isaka

voiced ð:

leather – レザー rezaa

algorithm – アリゴリズム arigorizumu

That's except when the following vowel is the one written in romaji or katakana as i. The sequences si and zi are impossible in Japanese, so you get shi and ji instead.

theater – シアター shiataa

smoothie – スムージー sumuujii

Vowel Substitutions

English has a much bigger vowel system than Japanese, so some vowels need to be changed when words are borrowed. This section will explain the basic articulatory seo_description of vowels (which involves explaining differences in English that you might not consciously realize because the spelling system obscures them) and how the Japanese and English vowels systems are similar and different. Then we'll see how the way Japanese changes the vowels makes sense.

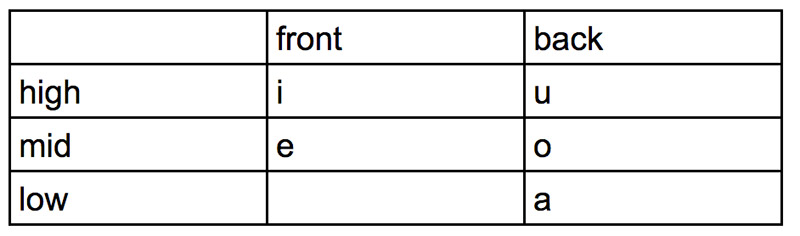

Linguists describe vowels in terms of height of the tongue and how far front/back the tongue is. The vowel system of Japanese is basically as follows:

When reading that chart, pronounce it like romaji (think eg. na ni nu ne no) and hey, you'll be reading phonetic transcription! Romaji vowels are the same as International Phonetic Alphabet vowels, and are consistent, unlike the many different ways English can spell the same vowel sounds.

The front and back differences are hard to feel intuitively, but you can probably feel your tongue going up and down when you go between extremes like i and a, for example. But trust the phoneticians, this is the deal.

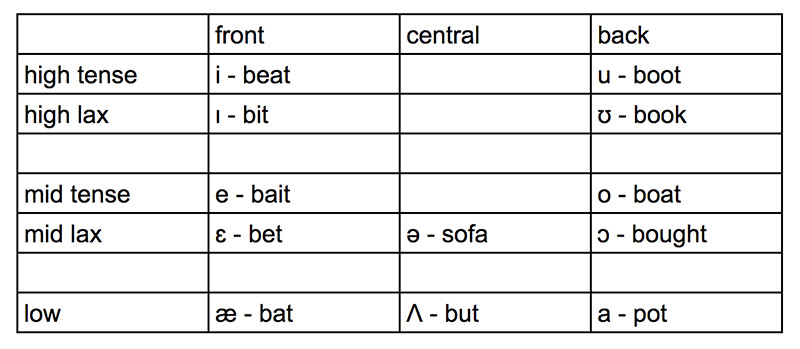

English has a larger vowel system. It's also very different by dialect, both in different countries and different parts of those countries, but a basic American English vowel system looks like the following. English vowel spelling is also about as unclear as a writing system can possibly be, so I've given the phonetic transcription and a sample word for each vowel.

Notes:

- The tense/lax difference can also be analyzed as a vowel length difference, but that is harder for native English speakers to get their minds around, so we're going to do it this way.

- If you're from California and some other parts of the US, you don't have the vowel ɔ; bought and pot have the same vowel, and the names Dawn and Don are pronounced identically.

- If you don't hear a difference between ə and Ʌ, neither do I. Generally ə is used in unstressed syllables like the second vowel in sofa, and Ʌ in stressed ones. If you Google a bunch of English vowel charts you'll also see differences in whether they're listed as mid or low vowels. In borrowings, Japanese treats ə /Ʌ as low, so that's how I'm doing it here.

Now that we've got this chart, you can probably figure out what the deal is. Japanese doesn't have the tense/lax difference, so the lax vowels are replaced by the tense ones. This is hard to see because the English spelling is inconsistent, so I've given English in phonetic transcription in the examples below:

- "gin" has high front lax [ɪ] in English, but high front tense in Japanese: jin

- "sense" has mid front lax [ɛ] in E, but mid front tense in J: sensu

- "looks" has high back lax [ʊ] in E, but high back tense in J: rukkusu

- "offside" has mid back lax [ɔ] in E, but mid back lax in J: ofusaido

(Personally I find the mid vowel e difference very subtle, but I have weird front vowels from growing up in New York City, so your mileage may vary.)

ə /Ʌ are treated as a pair in a similar way. Japanese doesn't have the kind of unstressed syllables that English does, so ə is basically treated like stressed Ʌ, and Japanese has no vowel in that space, so it takes the closest vowel it has, low a. We've seen that in words like guts, which has the ə /Ʌ in English pronunciation and comes out gattsu in Japanese.

Final Notes

There are many other things that go on with vowels that I don't have the space to go into. We're going to ignore vowel length and diphthongs, again, so this doesn't end up the length of a dissertation. But there are a couple more interesting points about vowels that I'll end with.

One is that you will see exceptions to these rules when words were borrowed via writing instead of by ear. For example, the word police has ə in its first, unstressed syllable. But it is a dictionary loan, so its pronunciation in Japanese follows the spelling instead: ポイス porisu. Or take radio, which if borrowed via hearing it would have been レージオ reejio, but was a dictionary loan, so it's ラジオ rajio, following the spelling, instead.

There's also one kind of interesting case where a consonant gets added in. This is the one case I didn't know the explanation for before I started writing this article, and it was driving me crazy because I have been listening to a lot of Kyary Pamyu Pamyu songs. Apparently Kyary thinks her name is the same as the English Carrie or Kari, so where did the added y come from?

Well here's the deal: the name Kari has the low front vowel æ in its first syllable. Remember, Japanese doesn't have that, it just has the low back vowel a. In most cases, æ is just replaced by a, the nearest vowel, and the frontness is lost. This is hard to even notice since the original English doesn't have different letters for these two vowels, but it's true: English "map" is [mæp], with the front vowel sound of "bat", but Japanese mappu has the back vowel sound [a] of "pot".

After k and g, though, along with this vowel change, y is often inserted:

cabin – キャビン kyabin

gamble – ギャンブル gyamburu

Why? Y is why. Y is a consonant called a glide. And in fact, it's a front glide.

We can see that y is front from various kinds of evidence that English y and the front vowel i are closely related. In fact, sometimes to us, they are basically indistinguishable, which makes certain parts of Japanese hard for English speakers. The most obvious instance of this: the word Tokyo. In Japanese that's two syllables, with the second one pronounced as written: kyou. But English speakers can't seem to help but turn that y into i, making the word into three syllables: "To-ki-o." Also, the first time I was in Tokyo, I almost got drastically lost until at the last moment I realized that there is both a Keiyō train line and a Keio train line. English speakers can't help but stick a y in the middle of that second one, so we can't really hear the difference either, which means you might end up way out in Chiba by mistake.

So inserting the y in Kyary is a way of preserving the frontness of the original vowel in Kari, not really a nefarious plan to confuse me when I'm just trying to enjoy a nice wacky music video. Now I know, and you do too!