In this series, Tofugu asks learners what Japanese learning resources and methods they use to study and why. Today, we talk to Dogen, a Kyushu-based YouTuber who creates comedic content mostly about Japan.

Dogen, while proficient in kanji and formal Japanese, specializes in speaking and creative writing. We hope you will be able to use his recommended tools and techniques to improve your Japanese. Take it away, Dogen!

Bodybuilders lift weights to get big, marathoners run cross country to develop endurance, and martial artists stretch to improve their kicks. What about you? Take a minute to think about the following:

What are your Japanese language goals and what are you doing to achieve them?

Much like an athlete, the language learner benefits from a regimen tailored to their personal goals. When I began taking Japanese classes at university, my goal was to develop a native-like accent. That said, I unwittingly studied in a counterproductive way; I spent the majority of my study time in the library, concentrating on kanji and grammar. "As long as I study long enough, one day I'll speak like a Japanese native," I thought. It wasn't until I began taking linguistics classes that I realized this was not true.

You don't want to be lifting weights if your ultimate goal is developing a strong crescent kick. Use tools that suit your language goals.

Some linguists say the human brain's ability to perfectly mimic foreign language stops at around 16 years old. My professor claimed 13. When I began researching this claim, I was 19. Needless to say, I felt a sudden sense of urgency, and consciously shifted my focus from kanji and reading comprehension to phonetics, which I studied intensely for the next two years. I strongly believe this decision is what brought my spoken Japanese to its current level; studying phonetics allowed me to nip dozens of bad speaking habits in the bud. Naturally, my kanji and advanced grammar abilities were comparatively weak for a long time, but I was able to supplement these later with grammar specific resources and SRS applications like WaniKani.

Below, I introduce the various resources I use to develop my Japanese speaking and creative writing abilities. While I strongly endorse these tools, I encourage all readers to assess their language goals before changing their Japanese learning plans and/or making any impulse purchases. Are you trying to get N1 certification? Are you working towards becoming a game translator? Is your dream to become a voice actor? Taking a couple days to step back and analyze your end game is a great way to determine which tools best suit your goals. Remember – you don't want to be lifting weights if your ultimate goal is developing a strong crescent kick!

TL;DR: use tools that suit your language goals.

Japanese Speaking Resources

The best way to improve your speaking abilities is to immerse yourself in a Japanese language environment while at the same time consciously striving to improve your phonetic awareness. The second part of this equation is critical; if you consume Japanese media without scrutinizing pronunciation and pitch-accent, you're likely to miss many of the sounds and pitch-accent patterns unique to Japanese. For example:

The Japanese word for mountain, 山 is romanized as "yama." The majority of native English speakers have no problem with the pronunciation of this word, as the "y," "a," and "m" sounds all exist in English. However, when it comes to pitch-accent, most English natives will unknowingly make a mistake, as 山 has a pitch-accent pattern unique to Japanese.

To elaborate, や has a low pitch, ま has a high pitch, and an attaching particle has a low pitch. Japanese natives and Japanese learners who have studied pitch-accent will hear "yaMA ga," because they are aware of it. On the other hand, Japanese learners who have never studied pitch-accent will only hear – and subsequently mimic – "yama ga." Most popular language programs don't cover this, however, because Japanese is usually comprehensible even if the pitch-accent is off; context does a great job of filling the gaps. But what about the learners who want to be more than comprehensible? What is the most effective way to study pitch-accent? Are there any resources that can help us develop phonetic awareness?

Fortunately, yes! Several extremely useful Japanese pitch-accent resources do exist – they're just not part of any larger, holistic program. The three main tools I use to study pitch-accent are:

- The macOS dictionary

- Prosody Tutor Suzuki-Kun

- Forvo

In the following video, I break down exactly how I use each of these sources to quickly (emphasis on quickly) check pitch-accent.

As you can see, these are truly fantastic phonetic resources. That said, they aren't without their limitations. While these tools are great for looking up the pitch-accent and pronunciation of individual words, they don't offer insight into truly practical information such as pattern frequency or conjugation-based pitch-accent change. There are resources that do cover this information, such as the Japanese Shinmeikai Accent Dictionary or the NHK Accent Dictionary, but they are unfortunately Japanese-based, which makes them inaccessible for beginner and intermediate learners.

This leaves the average Japanese learner with few options when trying to study Japanese phonetics – particularly pitch-accent – in detail. To combat this status quo, I created Japanese Phonetics, an online video series that teaches Japanese pitch-accent and pronunciation in simple English, with audio cues and visual graphs.

While not yet finished (I'm currently 18 episodes in, expecting to finish around 30-35), I can say with confidence that Japanese Phonetics is the Internet's most comprehensive – and more importantly, practical – Japanese phonetic resource. If you have never studied pitch-accent, I can guarantee that the first ten episodes will fundamentally change the way you hear, and consequently, speak Japanese. It's the information in this series, particularly the pitch-accent rules, that enabled me to reach my current level.

If you're not interested in Japanese phonetics but still want to improve your spoken Japanese, my number one piece of advice is to record yourself. You will, without fail, pick up on mistakes. There have been dozens of times I've been 100% convinced I was saying a word with one pitch-accent pattern (to the point I would fight with my Japanese friends) only to find out it was a different pattern after hearing a recording.

Mac users: you can simplify the recording process by using the following keyboard shortcuts:

- Command + Spacebar (launch Spotlight)

- Type: "quick" and press enter (launch QuickTime)

- Control + Option + Command + N (Create New Audio Recording)

This may seem like trivial advice but it makes a big difference. If you can be up and running in two seconds, you're much more likely to record yourself regularly. Naturally, these exercises aren't limited to Mac users. If you use a PC, you can download Audacity and add a shortcut to your desktop. For your phone, you can move the voice memo app to your homescreen.

The important thing is to create an environment that enables you to start recording yourself at a moment's notice.

If you want to improve your spoken Japanese, my number one piece of advice is to record yourself. You will, without fail, pick up on mistakes.

Once you've become comfortable with self-analysis, try having Japanese natives listen to your recordings through services such as Lang-8 and HiNative. Though these tools work best for grammar, if you're explicit about your intentions, users will be more than happy to provide pronunciation/pitch-accent feedback (keep in mind, not many natives can give in-depth feedback with regards to pitch-accent, though).

Useful tip: if you upload a recording of yourself to YouTube you can embed the video directly into a Lang-8 post. This is a truly great practice for getting out of your comfort zone. It's easy to be a big fish in a classroom of 25 Japanese learners – not the case when you're in an ocean of unbiased natives!

Speaking summary: If you're interested in developing a native-like accent, strive to be in a constant state of phonetic awareness. Pay as much attention to pronunciation and pitch-accent as you do to meaning. Use the macOS Dictionary, Prosody Tutor Suzuki-Kun, and Forvo to look up the pitch-accent for individual words, and consider signing up for Japanese Phonetics if you're interested in developing a strong understanding of useful phonetics rules and patterns. Record yourself if you've never tried, and use services like Lang-8 and HiNative to have your recordings checked by natives.

Japanese Creative Writing Resources

During my last year of university I became interested in creative writing. I enrolled in several courses, read novels I cliff-noted in high school, and started writing on a regular basis. After a few months, however, things began feeling counterproductive. I was majoring in Japanese linguistics, but spending most of my free time writing in English – not a model of efficiency.

Fortunately, I wasn't so much interested in English as I was in creative writing and literature as a whole. Thus, after a few weeks of deliberation I decided to switch my writing language to Japanese.

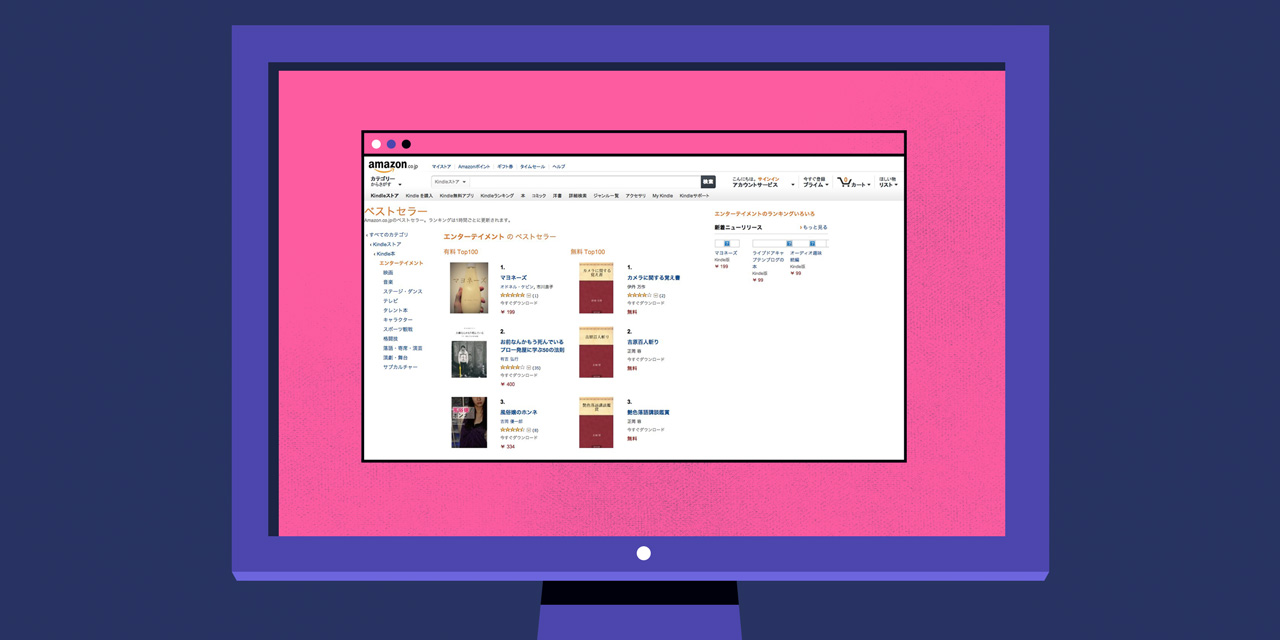

I spent essentially the entirety of my free time on the JET Program writing in Japanese. Let me rephrase that. I spent essentially the entirety of my free time on the JET Program trying to write in Japanese. For a long time, most of what I wrote was complete nonsense. That said, I did feel myself improving, and after three solid years of practice, I had an elementary, but readable voice. Toward the end of my contract I self-published a collection of short stories and a novella, the latter of which reached number one in the entertainment section of the Japanese Kindle Store.

Below I'd like to introduce the methods and resources I used to develop my Japanese creative writing abilities. I've purposely included the word "creative" here, as these exercises and tools aren't effective for something like business e-mail or LINE communication. They will, however, greatly refine your eloquence and sensitivity, both highly influential traits in an age of memes and Google Analytics.

At this point, the advice "read Japanese literature" is a given, so I'd like to instead suggest the following: go beyond Murakami Haruki. While Haruki is undoubtedly a bungou 文豪 (great writer), it's important to realize his highly readable prose is extremely idiosyncratic – especially when compared to that of other contemporary Japanese authors. Haruki, though extremely engaging, isn't as good for Japanese literature comprehension as he is for Haruki comprehension.

For learners looking to expand their literary lexicon, the authors I recommend most are the eccentric Kanehara Hitomi (Snakes and Earrings, Trip Trap), and the often-bleak, often-surreal Murakami Ryu (69, Audition). In terms of older literature, I'm fond of Mishima Yukio (The Sound of Waves, The Golden Pavilion), the literary genius often cited as the greatest Japanese writer of the 20th century. It wasn't until I began reading these authors that I was able to start appreciating the breadth of Japanese literature, as well as Murakami Haruki's unique position within said sphere. Exposure to a variety of styles and themes leads to perspective, which is critical for developing a unique voice.

When I began reading Japanese novels, I used an electronic dictionary to look up words. After a few months of reading in this way, however, I realized most words were going in one ear and out the other. Thus, I did what most learners do when trying to increase their vocabulary: I began making flashcards. As I became more interested in writing, words became clauses, and clauses became sentences. Naturally, many of these first entries were metaphors and similes. Here is an example from Murakami Ryu's 69:

- 仔馬のバンビみたいな 目だ。

- Her eyes are like Bambi's.

My notebook quickly expanded, however, to include "broken prose" – redundant phrases or fragments intentionally used to add variety and impact. Here is a brilliant example of broken prose from Kanehara Hitomi's Trip Trap:

- 胃が 痙攣していて、 体中が 震えて、 落ち着く 間もなく 襲ってくる 吐き気に、 本気で 死期を 感じていた。 次の 波に 怯えている 内に、ああこんな 思いをするくらいならパーティーなんてドタキャンすれば 良かった、というよりも 以前にフランスなんて 来なければ 良かった、というよりも 生まれてこなければ 良かったと 思う。

- I trembled in fear knowing the next wave of nausea was only seconds away. If I had known things would turn out this way I never would have come to the party. No, I never would have come to Paris. Cancel that, I would have aborted myself in the womb.

And another example, the opening line of Kanehara Hitomi's Mink:

- 大声で 叫びながら、 目の 前の 男に 体当たりをする 私。

- Me, screaming at the top of my lungs as I smash into the man.

This second example is a fragment. An incomplete or grammatically incorrect phrase – like this. That said, it's an intentional fragment – a taigendome 体言止め, or phrase that ends with a noun instead of a verb. Despite showing up fairly often in Japanese literature and copy, 体言止め are almost never taught in grammar textbooks or Japanese classrooms, as they usually don't show up in Japanese proficiency tests (or a lot of Murakami Haruki's works, for that matter). If you're interested in writing try to memorize this one today; when used properly, 体言止め can immediately add weight and variety to your prose.

Despite showing up fairly often in Japanese literature and copy, taigendome 体言止め are almost never taught in grammar textbooks or Japanese classrooms, as they usually don't show up in Japanese proficiency tests.

And so my notebook filled with quips, imaginative metaphors, and rhythmic fragments. Naturally, this notebook proved to be an extremely useful reference tool for my own writing, but over time it began to lose its effectiveness. By the time I started Mayonnaise (my novella), I actually had three notebooks, which made it near impossible to locate phrases in a pinch. To solve this problem, I took a weekend off and transcribed my notebooks into a search-ready Word file.

Later on, I began adding in my own native-checked essays. This eventually resulted in my「 万事ノート」(almighty note), a 207-page document filled with interesting phrases I can immediately reference while writing. The act of manually inputting long passages into Word may seem daunting, but this task itself is very effective for memorizing complicated phrases and sentence structure. I encourage anyone studying Japanese to create their own 万事ノート and leverage the search functionality of software such as Word and Pages; it's by far the most effective method I've found for learning to recreate "broken prose." Read, rewrite, reference, repeat.

Audiobooks are also a great resource for exposing yourself to Japanese prose. Find a short story (or single chapter from a longer work), perhaps 20-30 minutes long, and listen to it until you can recite the lines as they're said. During my time on the JET program I spent approximately three months listening to Natsume Soseki's 夢十夜 every day during my commute, and by the end of the third month I could talk along with almost the entire first chapter. The practice can get dull at times, but it's incredibly effective for learning new words and phrases without putting in too much effort. My one suggestion would be to incorporate some kind of active motion (such as driving, walking, cleaning, etc.) while listening. Though it may seem counterintuitive, engaging multiple areas of the mind through movement helps a lot with focus.

Of course, if your ultimate goal is to develop your writing abilities, you'll need to do a lot of writing. Don't be too concerned about your initial work; the purpose of establishing writing habits isn't to produce quality prose, but to find your voice. When I began writing I initially tried to mimic the styles of romantic greats such as Mishima – it was the crashing and burning that ultimately jump started my journey into comedy.

Rather than swinging for the fences your first time at the plate, concentrate on developing a strong batting stance. If you don't have any subjects in mind for your first pieces, try writing a daily journal or blog; these are just as effective for developing voice.

Finally, you'll want to get as much feedback from native speakers as possible. Lang-8 is the ultimate tool for this. If you're truly passionate about developing your writing abilities, consider signing up for a premium account. I've been a premium user for six years now and stand by the value 100%.

I will say, however, there is variety in the quality of the corrections you receive on Lang-8 (or similar services). Try searching for someone who seems to have a good command of both Japanese and your native language and contacting them directly. A language partner who knows your writing style (as well as the prose you're trying to develop) can provide much more effective feedback than someone who's checking your writing for the first time.

Creative writing summary: Read a variety of Japanese authors, and analyze the different ways they bend and break the rules. Combine audiobooks and movement to quickly saturate yourself with rich Japanese prose. Write often. Use Lang-8 to get your writing checked by native Japanese speakers and try to find an educated, reliable language partner.

These are the tools and practices I used, and continue to use, to improve my Japanese speaking and writing abilities. If you'd like to develop your accent and/or plan on getting involved with creative work such as game or anime translation (or scripting, for that matter), consider implementing some of these resources and techniques in your Japanese study plan. Finally, if you have any questions, feel free to contact me directly on Twitter @dogen.