Before all my past linguistics professors start to wail and compose angry comments, let’s get that deliberately sensationalist title out of the way: Really, no language is harder than any other language. Wherever a child is born, whatever language is being spoken there, that baby will learn its native language – or languages – just as easily.

The problem, though, is that we don’t get to choose where we are born. And if you’re a native speaker of English who wishes you could speak Japanese, starting over as a baby is not an option. But who cares what babies think? Talking about how easily babies learn Japanese does nothing but make me angry at those lucky Japanese babies and the annoying linguists who think this is a relevant answer to the question.

Of course what we’re really interested in, as adults, is how hard a language is to learn for an adult – and the answer to that question depends on where you’re starting. Yes, it will take me longer to get fluent in Japanese than in, say, Spanish (the Department of Defense has done the calculations, and if you’re studying Japanese, click that link at your own peril). But that’s purely because I am starting out as an English speaker. What makes Japanese hard is that it’s so different in structure from my native language, while what makes Spanish easy is that it’s much more similar.

There’s no answer to “how hard is this language for an adult,” only “how hard is this language for THIS adult.” Regardless of whether we’re talking about babies or adult learners, there’s no such thing as an easy or hard language in absolute terms. But as adult learners, we’re not interested in absolutes – for us, as with the English/Japanese/Spanish comparison, it’s all relative. And there are actually interesting things to say about some of the details and relative difficulty. There are features a language can have that are relatively rare in the world’s languages, so they’ll be hard for speakers of a lot of other languages. We could fairly call those features “difficult.”

And when we look at it that way, English has a fair number of difficulties, while Japanese – yes, Japanese – has some features that make it easy. What’s more, they actually share some features that make both of them hard for everyone else – which means that whichever one you’re starting with, you should at least be glad you don’t have to learn them both.

English vs Japanese: Pronunciation Battle

While no sounds are inherently harder for those irrelevant babies to learn to pronounce in their native language, some are inherently rarer – they occur in fewer of the world’s languages. This means that speakers of more languages are going to have trouble when they encounter them in a foreign language. And when it comes to these less common sounds, English has got a bunch of them.

Consonants

English has some consonant sounds that are extremely rare. To make matters more confusing, there are two of them that we write the same way, as th. Here are words that start with these two sounds and the symbol that linguists use to write them:

voiceless θ: thin

voiced ð: the

These consonants are found in less than ten percent of the world’s languages. This means that the vast majority of learners coming to English already can’t pronounce these sounds. Most of them will end up substituting either t and d or s and z depending on the language they started with. Japanese speakers will tend to use s and z as you know if you’ve read our Guide to Loanword Phonology, as in the following:

voiceless θ: marathon – マラソン marason

voiced ð: leather – レザー rezaa

What’s particularly cruel to non-native English learners is that we not only have this annoying sound, there’s no way to avoid it, because it’s in words that are used constantly and have no real alternative, like “the” and “that” and “there”. It’s almost like we wanted a way to out someone as a non-native speaker every time they open their mouth.

Another weird consonant is the way R is pronounced in American English. In the vast majority of languages that have some kind of R sound, it’s either a trill or a quick tap against the alveolar ridge (that ridge behind your front teeth). This thing we do in American English where we bunch up the tongue in the middle of our mouth is basically designed to torture nearly everyone else on the planet.

Japanese, in contrast, has no rare consonants. The only candidate might be the exact pronunciation of the f sound, but that only occurs in a limited context, and isn’t going to trip you up every time you try to use the definite article.

Advantage: Japanese

Vowels

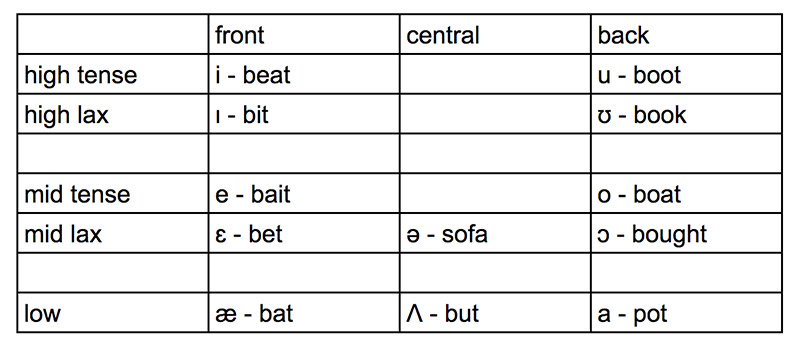

English has only five vowel letters but many more actual vowel sounds. We need special symbols to talk about them precisely:

Compared to other languages of the world this is an above-averagely large number of vowels, and English can be fairly described as having an “unusually rich and complex vowel system, and a great deal of variation in vowel pronunciation across dialects.”

“Unusually rich and complex.” That’s a good thing if you’re talking about, say, cuisine, or literature. For learning a language it just means trouble. For example, the difference between the tense/lax pairs in the chart above is hard for just about anyone learning English – with the result that someone with a strong non-native accent has trouble pronouncing words like “seen” (tense vowel) and “sin” (lax vowel) differently – they both sound like “seen.”

In contrast, Japanese has what is basically a classic system of vowels, which is 5, corresponding to the five vowel letters of our alphabet. (The u sound has a slightly unusual pronunciation but you can get by without ever noticing it.)

So English speakers learning Japanese already have all the vowels they need. There are slight phonetic differences, which is why you probably have a detectable accent, but you can get close enough by using vowels you already know. That’s much easier than the poor Japanese learner, who has to learn to pronounce vowels that they never knew existed.

Advantage: Japanese

And that’s before we’ve even addressed the other thing, which is that in English we only have five letters to spell all of those vowels with, AND we use them differently than all other languages. We’ll get to that later.

Syllable structure/consonant clusters

Individual sounds aren’t the only thing you might find difficult in a new language. It’s also how those sounds are put together, and again, here English poses more of a challenge.

Although it’s kids’ stuff compared to some languages (hello Russia and neighbors), English is more complex than average when it comes to how many consonants you can cram into one syllable.

In comparison, while Japanese doesn’t have the simplest possible syllable structure, it’s pretty close. In some languages, the most complicated possible syllables are sequences of one consonant and one vowel. Japanese only allows a tiny bit more complexity than this. If you’ve read our guides to the Japanese past tense and English loanwords in Japanese, you know that the consonants that can occur next to each other in Japanese words is very limited – certain identical consonant sequences and certain nasal-consonant sequence – and only in the middle of a word. That’s why English words borrowed into Japanese tend to have a bunch of vowels added to them.

The result is that most Japanese sound sequences are going to be possible in whatever other language the learner is coming from, so they don’t present a challenge. The most unusual thing is those sequences of two identical consonants (what linguistics geeks call geminates), but once you learn the trick to those, it’s the same for all of them. That’s much less complicated than the variety of consonant sequences you have to wrap your tongue around in English, where you can begin a syllable with three consonants (strike), end it with four consonants (texts, which actually ends in the four sounds ksts), and of course there are various different two- and three- and four-consonant possibilities.

And don’t even get me started on how crazy English stress is.

Advantage: Japanese

English vs Japanese: Morphology Battle

Morphology is what linguistics geeks call the study of the structure of words. I’m not going to address syntax (sentence structure) as such in this article, but there a few things languages often do with words to make them fit into sentence structure that both Japanese and English learners can be happy we don’t have to worry about.

Verb conjugation is pretty simple in Japanese. There’s no agreement for person – compare to the Spanish, say:

yo digo – I say

tú dices – you say

él dice – he/she says

nosotros decimos – we say

vosotros decís – you plural say

ellos dicen – they say

In Japanese, it’s all “hanashimasu” no matter who is doing the hanashimas-ing. In English, it’s only a hair more complicated – say/says is the only difference.

In both Japanese and English, we don’t have to learn noun gender, that painfully arbitrary stuff that means that in Spanish you have to use the masculine form of “the” for el lago “the lake” and the feminine form for la mesa “the table” even though these things clearly have no sex at all.

We also don’t have to learn noun case – this is the thing wherein some languages, nouns take a different form depending on whether they are subject, object, etc of a sentence. The classic example is Latin: “girl” is different depending on the role the girl plays in the primary_sentence:

puella if she’s the subject, like, “the girl is eating sushi”

puellam if she’s the object, like, “the dog bit the girl”

puellae if she’s the indirect object, like, “I gave sushi to the girl”

(And that’s only one declension – nouns are divided into several sets, each of which has different endings.)

I haven’t really researched morphological differences thoroughly enough to give a score, but I’m going to do it anyway. I give Japanese the honorary award for being harder because of another thing: the different forms of the numerals for counting different kinds of objects. If you’re counting a bunch of pencils you go “ippon, nihon, sanbon…” and if you’re counting a bunch of dogs you go “ippiki, nihiki, sanbiki….” and if you’re counting sheets of paper you go “ichimai, nimai, sanmai….”

While it’s true that there are also general numbers for counting, and that most people can probably go their whole life without needing to count a bunch of small animals, I’m giving Japanese extra credit for this one. Back in the day when I taught intro linguistics, I used to tell students there were languages like that because the textbooks said there were, but I’m not sure I really believed it. Imagine my surprise when I started studying Japanese…

Advantage: English, because I said so.

English vs Japanese vs Everybody Else: Vocabulary Battle

Because of their history, both English and Japanese have unusually complicated vocabulary systems. English is basically a Germanic language, but took in a lot of words with Romance/Latin roots from French at the Norman Conquest. Likewise Japanese has a core of native vocabulary and then took in a whole bunch of words from Chinese. Both histories result in similar complications that are a pain in the ass for second language learners.

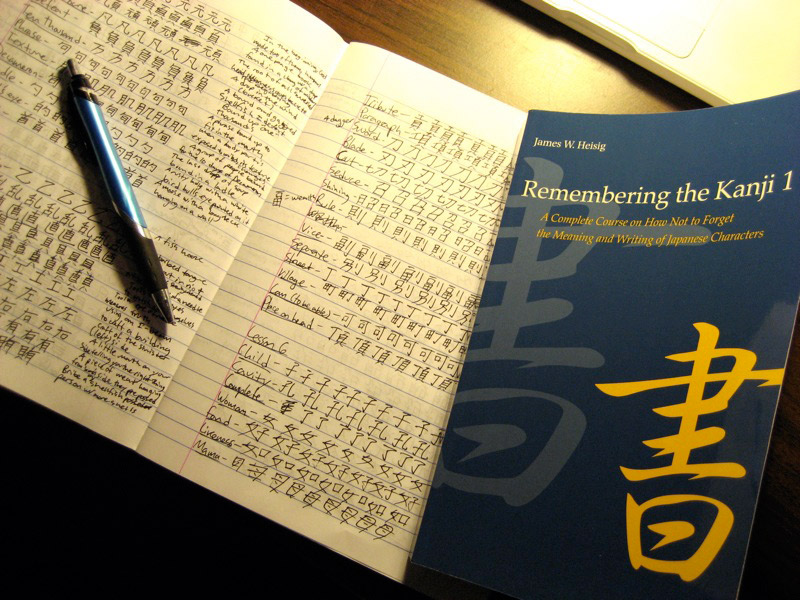

In Japanese, this is why you’ve got different kun/on readings for kanji – basically the language has a whole bunch of pairs of synonyms, with different historical origins, that are written with the same character. For those of you who are not (yet) actually playing along at home by studying Japanese, a quick explanation:

Let’s say you’re learning the kanji 豚, which means “pig.” There are two ways to pronounce that same character: the historically native Japanese, “buta,” and the historically Chinese, “ton.” Which way you pronounce it depends on what word it’s in: 豚肉 “pork” is buta-niku, whereas that delicious fried pork cutlet 豚カツ is tonkatsu.

But while you’re wailing and gnashing your teeth about how much this means you have to memorize in learning Japanese, what you probably don’t realize is that English has basically the same problem for the language learner. There are many cases where the relationship in meaning between two words is completely obscure because we use a Germanic root for one and a Latin root for the other.

For example, “mouth” is a Germanic noun, but when we make an adjective meaning “related to the mouth” we use the Latinate root, “oral.” Compare this to German, where the word for “mouth” is mund and to make an adjective meaning “related to the mouth” we mostly just stick a suffix on the same word: mündlich. Which would you rather have to learn?

Or compare it to Latin itself: In English, we have the German word “hear” but “related to hearing” is “auditory.” In Latin, “hear” is audire and “related to hearing is” – wait for it – auditorio. Both contain the root audi, and you can derive all kinds of words related to hearing from that root in consistent ways. Latin is another language that is supposed to be “hard,” but for that pair of words, I know which would be easier to memorize. And there are a lot more pairs like this in English, basically most of the vocabulary for body parts and functions (heart/cardiac, see/visual…. your foot doctor is a podiatrist… etc.)

There are also segments of English vocabulary that do the same thing but add confusion by being less systematic. For example, we borrowed a lot of words relating to food from the French, but not all, with results like the following:

The word for a cow in a barnyard is cow, but in the kitchen it’s beef; likewise, you’ve got a pig in the pen and pork on your plate. Compare to Japanese where niku is meat, pork is buta-niku or ton-niku, both “pig meat,” and beef is gyuu-niku “cow meat.” I know which pairs I’d rather have to memorize, right? And then just to keep those foreigners on their toes, we call chickens, lambs, ducks and any number of fish the same thing whether alive or grilled. I’m sure this results in a lot of people digging around in the dictionary wondering what the word for “chicken meat” is – expecting something just as unrelated as the words “cow” and “beef” – and then wanting to kick someone when it turns out to be “chicken.”

Advantage: Neither. Speakers of other languages should be equally sorry they are learning either Japanese or English.

English vs Japanese vs Everybody Else Including Native Learners: Writing Systems Battle

Both English and Japanese have difficult writing systems. Kanji kicks everyone’s asses – it takes Japanese kids a long time to learn too. And English has a ton of irregularities that make it harder to learn to read than most languages that use the Latin alphabet. There’s probably no winner in this battle other than people who manage to go through life without having to learn either, but English is probably a lot harder than you realize if you’ve been reading it all your life.

Japanese combines two distinct types of writing systems. One is the familiar type that represents pronunciation: when you see the kana か, you know to move your mouth to make the sound “ka” come out. The other element of the writing system, kanji, represents morphemes, which is what linguists call the basic elements of meaning that make up words. Here’s another example, like the one we saw above for the word pig, just to make sure you get it if you’re not already studying the language: When you see the kanji 見, you know that the word will be something related to seeing – you have an idea of the meaning – but you don’t know whether to pronounce it mi or ken without knowing the particular word it’s part of.

If you speak a language that uses an alphabet, kanji can seem crazy. Why make people memorize thousands of characters when they could just memorize 26 letters and combine them any way they need to? But one important thing to realize is that writing systems aren’t designed to be easy for the learner – they evolve to be useful for the fluent speaker. After all, you spend a tiny period of your life learning to read, compared to the years you’ll spend reading afterwards.

And in Japanese, once you’ve learned the system and the language, reading and writing kanji is actually more effective than using a system that represents just pronunciation (as anyone who tries to read Japanese in just romaji will eventually realize). The reason for this basically follows from what we learned earlier about the sound system: Japanese has a relatively small sound system and allows only relatively simple syllables. That means there’s a limited number of ways you can combine sounds into words, so there are many homophones – words that sound the same but have different meanings. If I walk up to you and say tsuku – or if you read つく – you have no way of knowing what it means unless there some context to rely on, because it can mean any of the following and more:

- 吐く to breathe

- 点く to catch fire

- 着く to reach

- 突く to poke

- 付く to be attached

- 憑く to haunt

- 浸く to be pickled

That’s a modest case, because I made it two syllables. Go type “ki” into a Japanese dictionary and you’ll get a much more impressive list that I couldn’t stand the idea of typing here.

Of course in writing, like in the list above, which meaning is intended is clear, because they’re all different kanji. Native Japanese speakers will sometimes disambiguate even in speaking by drawing a kanji in the air with one finger. So despite the time it takes to learn, the writing system makes sense given the structure of the language.

And in fact, if you want to argue in favor of a writing system that represents pronunciation, you probably shouldn’t do it by talking about how much easier it is to read and write English. There are plenty of languages where the alphabet reliably tells you how to pronounce a word, but English isn’t one of them.

There are even ways that English is a similar kind of mixed system, consistently representing morphemes rather than sounds. A common word that’s hard for second language learners to pronounce is “says.” They look at it and figure, just pronounce “say” and put the sound s at the end, right? Sadly, nope. It’s more like “sez” (a spelling you sometimes see in comic books to indicate casual speech or dialect, which is actually pretty weird since that’s the standard pronunciation).

So why don’t we write it “sez”? Instead of representing the pronunciation, the writing system preserves the relationship of meaning instead: you know that “say” and “says” are forms of the same verb by looking at them, even though it’s not clear how to say them. Just as if the sequence “say” were a kanji character!

A reversed but still similar case is the words to/two/too: they are all pronounced the same but written differently, just like all the different kanji for “tsuku.” Yeah, you’d be able to tell which was which by context most of the time. But there’s no real pressure on the writing system to regularize those spellings, since they do serve a function by making those words easy to distinguish at a glance.

So some apparently irregularities in English writing make some sense, the same way kanji makes more sense once you think about it. Unfortunately, this is not an excuse for most of them.

The basic problem with English spelling is a historical one. (Here’s a cute video that explains much of it). Our spelling was standardized by the invention of printing at an unfortunate time – before a bunch of pronunciation changes took place. This accounts for some obvious things like the extra letters in a word like “thought” – there used to be a sound where the gh is, but it went away – or “cough” – where the pronunciation of the sound represented by gh changed to f.

But the worst part of all is the vowels. To start, there’s the Latin alphabet. We got it from Latin, which only has five vowels. Since we have more vowel sounds than that, as I mentioned earlier, we have to use combinations of letters to represent some of them. Some of which aren’t even combinations of adjacent letters: pity the second language learner who has to learn that the e at the end of bite isn’t pronounced, but is stuck on so you know it’s a different vowel than the word bit.

And the additional historical problem here is that as a result of something called the Great Vowel Shift, we use those basic vowel letters aeiou differently from everyone else. In other languages that use the Latin alphabet, the vowel letters are pronounced the way they’re pronounced in romaji: ka, ki, ke, ko, ku. To everyone else, ki is how you write what we’d write “kee.” That’s nowhere near the vowel in “kite.” Likewise, the vowel in ka is nothing like the vowel in the word “mate.” There are enough confusing features of English spelling that you can write a poem like this one:

Dearest creature in creation

Studying English pronunciation,

I will teach you in my verse

Sounds like corpse, corps, horse and worse.

I will keep you, Susy, busy,

Make your head with heat grow dizzy;

Tear in eye, your dress you’ll tear;

Queer, fair seer, hear my prayer.

Pray, console your loving poet,

Make my coat look new, dear, sew it!

Just compare heart, hear and heard,

Dies and diet, lord and word.

Sword and sward, retain and Britain

(Mind the latter how it’s written).

…that goes on quite a bit longer if you follow that link. While you may complain because you can’t look at a kanji and know how to pronounce it, I think most speakers of English as a second language would feel the same way about trying to read that poem.

Basically, when it comes to writing, speakers of nearly any other language should be equally sorry they are learning either Japanese or English, when they could have chosen any number of languages where the alphabet consistently represents actual pronunciation. The only possible difference is that speakers of Chinese probably have an advantage learning kanji, but the characters are not the same in both languages and certainly not pronounced the same. As one native Chinese speaker explains it, it’s more just “after learned thousands of Chinese characters from young and having got extremely familiar with such writing system already, you hardly have reason fearing learning a couple of hundred more of them.”

Advantage: Neither, with maybe a slight advantage to Japanese just because there are so many millions of native speakers of Chinese.

Can’t Complain

So there you have it – at least some small but interesting portion of it – when we look across the languages of the world and see where Japanese and English compare. Yeah, Japanese is not a piece of cake if you’re a native speaker of English. But anyone trying to learn your language will probably want to punch you if they hear you complain, and they’d be entirely justified. So we probably better keep our whining to ourselves.