"Itadakimasu" is an essential phrase in your Japanese vocabulary. It's often translated as "I humbly receive," but in a mealtime setting, it's compared to "Let's eat," "Bon appétit," or "Thanks for the food." Some even liken it to the religious tradition of saying grace before eating.

But the uses for itadakimasu extend far beyond food. And though its roots are ancient, saying the phrase before meals is a fairly recent Japanese custom. Get ready to dig in. You are going to learn the history, uses, meaning, and philosophy behind itadakimasu.

The Meaning of Itadakimasu

In its simplest form, Itadakimasu 頂きます is used before receiving something. That's why the most common itadakimasu translation is:

- 頂きます(いただきます)

- to receive; to get; to accept; to take (humble).

This explains why you say it before you eat. You're "receiving" food, after all.

Itadakimasu (and its dictionary form itadaku 頂く) comes from Japan's roots in Buddhism, which teaches respect for all living things. This thinking extends to mealtime in the form of thanks to the plants, animals, farmers, hunters, chefs, and everything that went into the meal.

There are two kanji for itadaku:

- 頂く

- 戴く

Both are correct but the itadakimasu kanji 頂 is more common.

How to Use Itadakimasu

Knowing the itadakimasu meaning is one thing, but you still have to learn its pronunciation and when to use it.

Itadakimasu Pronunciation

- いただきます。

The audio clip above will give you a model for the itadakimasu pronunciation. But to really understand how to pronounce this word (and all other Japanese words), you should learn how the Japanese syllabary works with our hiragana guide.

Performing Itadakimasu

Saying itadakimasu before a meal is a significant piece of Japanese etiquette, so it's important to learn how to do it right. Usually everyone will say the phrase together, but it's also normal for each person to say it individually as they begin eating.

Performing itadakimasu before a meal is simple and has only four steps:

- Put your hands together

- Say "itadakimasu"

- Bow slightly

- Pick up your chopsticks and start eating

Below are Vines that show these steps in action, with slight differences in body language and enunciation. How you perform itadakimasu will depend on the situation and the people you're eating with. So use common sense and adjust your approach accordingly.

Polite:

Normal:

Casual:

The only major difference in any of these examples is the use of hands. In the casual demonstration, you'll notice Mami doesn't put her hands together. Other than that, the differences are subtle and won't impact the people around you much from situation to situation. Performing itadakimasu at a meal is not like tea ceremony. As long as you follow the steps above and match the politeness of people around you, you'll be fine.

When to Use Itadakimasu

As we mentioned earlier, itadaku means "to receive" or "to accept." But it's not a direct translation of the concept in English. There are certain situations where it's best not to use itadakimasu.

Here's your general rule of thumb:

You can use itadaku when you're offered an actual physical thing. It’s like you are saying, "I’ll take it," in a polite way.

Gloves, video games, tire irons, wigs, replacement basketball nets, you name it. If it's a physical object being offered to you, you can use itadaku to receive it.

A typical exchange might go like this:

- A: この 魚いりますか?

- A: Do you want this fish?

- B: そうですね。いただきます。ありがとうございます。

- B: Sure. I’ll take it. Thank you.

You can use itadaku when you're offered an actual physical thing. It’s like saying, "I’ll take it," in a polite way.

Be aware of your politeness level when using itadaku. Even though it's a more polite version of morau 貰う, it's not much more polite if you don't conjugate the plain form (itadaku) into the polite form (itadakimasu).

For example, the politeness of these sentences is basically the same:

- いただく。

- もらう。

But conjugate them into the polite form and itadakimasu becomes much more polite than moraimasu:

- いただきます。

- もらいます。

That's some major social etiquette power packed into one conjugation! But if you want to kick your politeness to the max, you can use the following super formal versions of itadakimasu:

- 有り難く 頂きます

- 有り難く 頂戴します

- 有り難く 頂戴 致します

They all mean "I'll take it," but at much higher politeness levels than itadakimasu. You probably don't want to use these unless you're receiving a gift from the Emperor or Shigeru Miyamoto.

Other Uses of Itadaku

What if you're offered something non-physical, like advice, a hug, a ride to the airport, or an opportunity?

- Short answer: Don't use itadakimasu to receive non-physical things.

- Long answer: You can use itadakimasu to ask for non-physical things (in very specific ways).

For example, you can't use itadakimasu to receive advice after it's offered, but you can use it to ask for advice:

- あなたのアドバイスをいただきたいんです。

- I want your advice.

- アドバイスをいただけませんか?

- Can I get your advice?

- コウイチ 大先生からアドバイスをいただきました。

- I got advice from the Great Teacher Koichi.

Asking is okay, but it would be weird to say "コウイチ 大先生のアドバイスをいただきます" (I’ll take the Great Teacher Koichi’s advice) because the advice is already given. A better way to convey this idea would be:

- コウイチ 大先生のアドバイスに 従うことにしました。

- I've decided to follow the Great Teacher Koichi’s advice.

Rides to the airport, train station, or anywhere follow the same logic. You can use itadaku to ask for a ride, but not to receive one. For example:

- 家まで 乗せていただきたいんです。

- I want a ride to my house.

- 飛行場まで 乗せていただけませんか?

- Could you give me a ride to the airport?

You can also use itadaku to talk about how you received a ride. Like so:

- 昨日はビエトさんに 駅まで 乗せていただきました。

- Yesterday, I got a ride to the station from Viet.

If someone offers you a hug, don't open up your arms and say "itadakimasu." That would be weird. Hugs are between friends and family, so using a polite expression to receive it is weird. The only situation we can think of where itadaku and hugging go together is if you're dating your boss and are politely requesting a hug:

- 抱きしめていただけませんか?

- Could you hug me, please?

If someone offers you a hug, don't open your arms and say "itadakimasu." That's weird.

But even this is weird, situationally speaking. And dating your boss is probably against company policy. You don't want to get in trouble with HR.

One of the few non-physical things you can take with itadaku is an opportunity. But you can't just say "itadakimasu" when someone offers you a chance to speak at a wedding. You have to say something like, "I'd like to take the opportunity to…" Here are some ways to do that:

- 書くのは 得意ではありませんが、あの 日 私に 起きたことについて 書かせていただきます。

- I’m not good at writing, but I’m (humbly) going to write about what happened to me on that day.

- それでは、 歌わせていただきます。

- Okay, I’m (humbly) going to sing now.

As you can see, using itadaku can get pretty nuanced. The more Japanese you learn, the more you'll understand how and when to use words like this. But for now, this is enough to get you started.

Itadakimasu History

When you grab chopsticks, you should thank all nature and living things, the Emperor, and your parents.

ーPassage from the Koukou Michibiki Gusa, 1812

The kanji for itadaku 頂 means mountaintop. The original meaning of itadaku is "to put something over the head" or "to wear on one's head," playing off the upward-ness of the mountain motif. It wasn't long before the word would become associated with receiving things, especially food.

Buddhism came to Japan during the Asuka period, bringing with it a "raising up" action when receiving items from people of high status, or when taking food or drink originally offered to gods (osagari お下がり). So naturally itadaku, a verb meaning to raise things above your head, started to be used as a humble form of words meaning "to receive," like morau 貰う and choudai suru 頂戴する.

But it wasn't until centuries later in 1812 that the mealtime itadakimasu started to come into its current form. A book called Koukou Michibiki Gusa 孝行導草 was published in Japan. It was an etiquette guide for daily life, and in it there is a sentence which historians point to as the origin of the modern mealtime itadakimasu:

- 箸 取らば、 天地 御代の 御恵み、 主君や 親の 御恩あぢわゑ

- When you grab chopsticks, you should thank all nature and living things, the Emperor, and your parents.

After this book was published, the idea of giving thanks before a meal was spread by the Jōdo-shinshū sect Buddhism. Though the monks did a good job popularizing the habit, not everyone in the country got the memo. A 1983 study by Japanese historian Isao Kumakura revealed that "itadakimasu" remained a regional practice until the early twentieth century. He surveyed people from all over Japan who were born in the Meiji and Taisho eras, and asked them about their habits growing up. According to the results, not all of them said "itadakimasu" before eating. So when did the mealtime phrase become a nationwide custom?

According to a book by Shoyo Yoshimura, it took hold during the early Showa era when education was governed by Imperial Japan. Teachers made students thank all living things, the emperor, and their parents before eating. They would end their thanks with "itadakimasu." This pledge was called shokuji-kun 食事訓, from 食事 meaning "meal" and 訓 meaning "lesson" or "doctrine." It is very similar to the passage from the Koukou Michibiki Gusa mentioned earlier.

Even though the origin of itadakimasu stretches back to the Asuka period, its current form has only been around for about 75 years. That means there are still people alive today who remember a time before Japan used itadakimasu nationwide. Who knows what the next evolution of this custom will be?

Put Your Hands Together! (Or Don't)

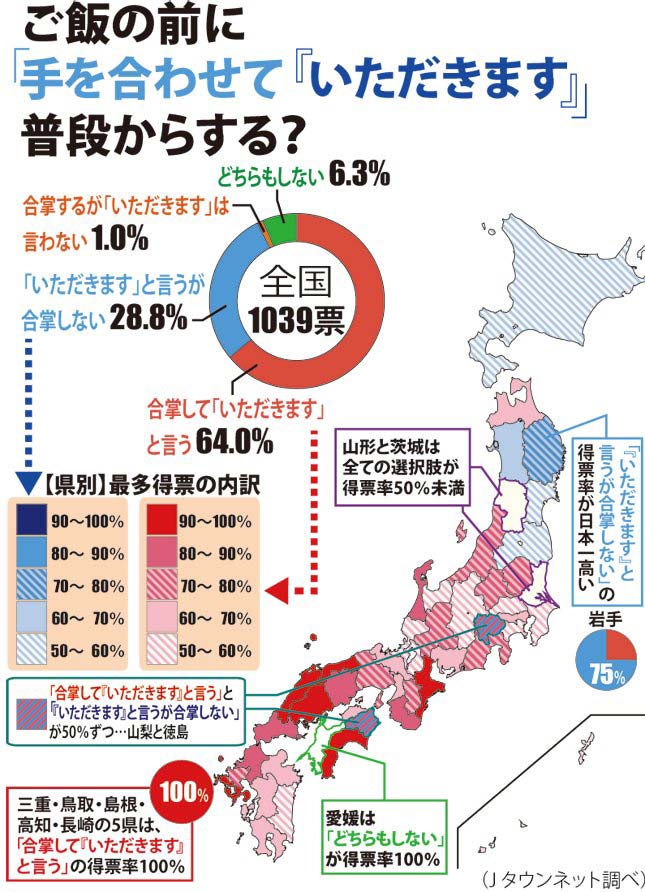

Though saying "itadakimasu" before a meal has taken hold in Japan, it's still not practiced the same way nationwide. According to research conducted by J-town:

- 64% of Japanese people put their hands together when saying "itadakimasu"

- 28% say "itadakimasu" and do nothing else

- 1% put their hands together without saying "itadakimasu"

- 6.3% don't do anything

Apparently, the differences in behavior depend on region. Remember how we said "itadakimasu" was originally spread by the Jōdo-shinshū sect of Buddhism? The followers of Jōdo-shinshū were taught to put their hands together and slightly bow while saying "itadakimasu." Hiroshima is well-known for its high concentration of Jōdo-shinshū temples, so much that followers from West Hiroshima even have a special name, aki-monto 安芸門徒. In the survey, 92% of people in Hiroshima said they put their hands together (note the deep red color of Hiroshima on the map). In fact, the entire western section of Japan is colored red, so apparently the past work of Jōdo-shinshū is having a lasting impact on the behavior of people to this day.

The Heart of Itadakimasu

In Japan, there's a saying,

- お 米 一粒 一粒には、 七人の 神様が 住んでいる。

- Seven Gods live in one grain of rice.

This emphasizes the idea that each bit of food is important.

The heart of the itadakimasu ritual is one of gratitude and reflection, even if only for a moment. In this light, starting a meal with "itadakimasu" implies you'll finish all of it. Something gave up its life for the meal, so it can be considered disrespectful to leave big chunks of food behind. Next time you see one last grain of rice in your bowl, don't be afraid to spend time trying to get it out.

But as we've seen, the gratitude of itadakimasu reaches beyond the dinner table and into our everyday lives. Whatever you receive, be it a hat, a job, or a ride to the airport, receive it with appreciation. Because the heart of itadaku is a thankfulness for the things you've been given and a determination to make the most of what you have.