- 元気(げんき)

- lively, full of spirit, energetic, vigorous, vital, spirited, healthy, fit, the basic energy of the universe that flows through everything

O genki desu ka? Hai, genki desu.

When you begin learning Japanese, one of the first words you run into is genki (元気). Classroom students tend to learn "Ogenki desu ka?" (How are you?) before they learn hiragana, katakana, or any grammar. Heck, even one of the most popular Japanese textbooks is named Genki!

But the meaning of this pervasive Japanese word is muddy. And while most dictionaries translate it as "good health," "spirit," "pep," or "vigor," there's more to it. In fact, if your general idea of genki is just the typical "energy" translation, you may be using it wrong.

Take heart and remain genki, though. We're going to clear up all that confusion right now. By the end of this article, you'll have a much clearer idea of where, when, and how to use genki.

- The Kanji for Genki

- The History and Etymology of Genki

- Genki As Something You Can Be

- Genki as a Thing That You Can Do Something With

- Do Things "Genki-ly"

- Other 元気 Terms

- Download the Genki Example Sentences

Prerequisite: This guide is going to use hiragana and some katakana, so we highly recommend you learn them beforehand by reading these (and most of our) guides. Don't worry! They can be learned in a day or two using our system. You can always come back when you're ready. For kanji you don't know, we recommend looking them up in a Japanese dictionary. Or, perhaps you could just go learn kanji? If you do it right, it's not as hard as everyone says.

Before you move on: We also recorded a podcast about the word "genki" and all its uses, though we highly recommend you read the article and listen to the podcast episode (instead of just one or the other).

And if you want to be nice, you can subscribe to the Tofugu podcast wherever podcasts go to live out their final years. Okay, back to the words version!

The Kanji for Genki

To properly understand any new Japanese word, it's a good habit to begin by dissecting its kanji. 元気 breaks down like this:

- 元 (げん) — origin, source, foundation

- 気 (き) — energy, spirit, mind

The 元 (origin) is self-explanatory, but the idea of 気 (energy, mind) is more abstract. Have you ever watched a Chinese martial arts movie or heard a yoga instructor talk about "centering your chi" or "focusing qi"? Well, 気 is the same idea. In fact, it's the same word: the Japanese 気 evolved from the Chinese 氣 (which is all that chi/qi stuff). Essentially, it's the vital energy—the life force—that animates the body and all matter in the universe.

One visual representation for 気 you might know comes from the Dragon Ball series. When Dragon Ball characters "power up," they're charging their 気. When Goku uses his spirit bomb attack, he collects the 気 from all living things on Earth, which he then redirects towards whatever menacing alien he's trying to defeat.

That's 気. When you put 元 and 気 together, their combination means "origin of energy" or "life force." In general, this can be thought of as your health, your energy, the energy of living things, or the universe.

You're probably starting to see why defining genki is so complex. To understand the concepts behind this word more clearly, let's go get a PhD in Eastern medicine.

The History and Etymology of Genki

The contemporary meaning of 元気 is a little abstract. It refers to a kind of "original energy," something from the universe, something from your mind, or… something. But it also refers to your health and can describe your well-being. How did two nebulous concepts get packed into one word? You can thank Chinese medicine.

China was a huge influence on Japan (just look at kanji and their readings), and Japan's adoption of Chinese medical practices included two words: 元気 and 原気 (pronounced yuán qì in Chinese and げんき in Japanese). Both refer to the fundamental energy that makes up all things. These two words are the source of the modern 元気's "original energy" definition.

- 元 — origin, source, base

- 原 — original, primitive

- 気 — energy

Yet there was a third genki, aside from these two, which also came from Chinese medicine.

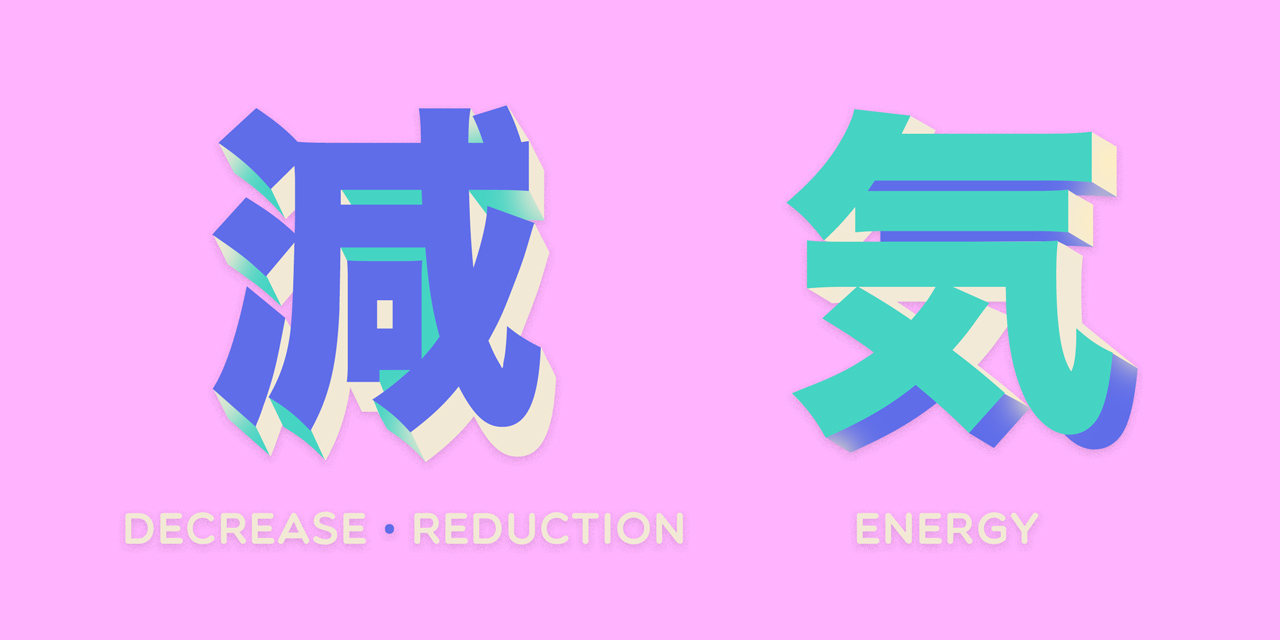

This 減気 (げんき) literally means "decrease energy," and was used when someone was recovering from an illness: getting better.

- 減 — decrease, reduction

- 気 — energy

Wait, what? Why would feeling better decrease your energy? Shouldn't it be the other way around?

Chinese medicine is tied to the philosophy of yin and yang—how energy can be either positive or negative—and how maintaining a balance between the two is essential for good health. Decreasing your negative energy (or sickness) would naturally make you better. You can find examples of this usage in a collection of prose from the late Heian period (794–1185) called Konjaku Monogatarishū 今昔物語集 (Anthology of Tales from the Past):

- 来ヲ経て此ノ病少シ減気有リ

- Some days passed and this illness has eased a bit.

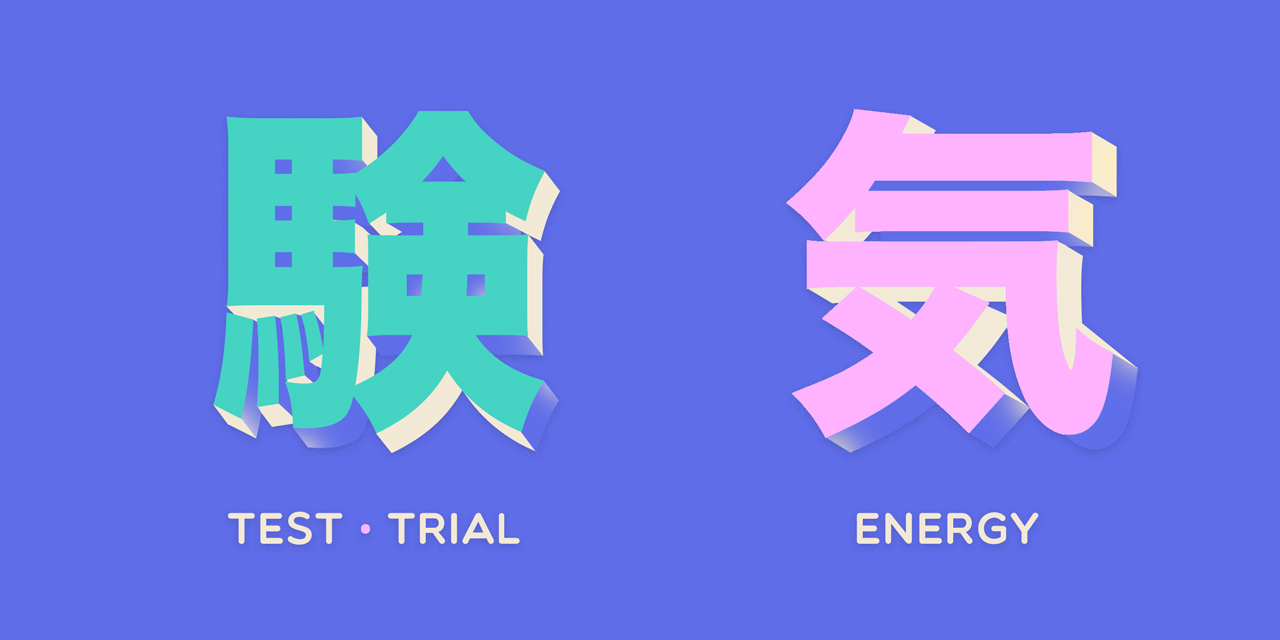

By the Edo period (1616–1867), encounters with Holland and Portugal had introduced ideas from Western medicine into Japanese life, and the 減気 form of genki was replaced by a newer one: 験気.

- 験 — test, trial

- 気 — energy

How did two nebulous concepts get packed into one word? You can thank Chinese medicine.

Rather than "decreasing your bad energy," in the Chinese medical sense, this new word meant "recovery as the result of testing / medical treatment," in the Western medical sense.

If you're having trouble keeping all this straight, you're not alone. In those days, folks were navigating four different forms of genki, sometimes interchangeably. But, usage gradually shifted. By the Meiji period (1868–1912), only one genki remained—the one we use today, and it incorporates ideas from all four original forms.

The "decrease energy" and "test energy" meanings got simplified, becoming "healthy" and "vigor." The "origin-of-all-energy-for-all-matter-in-the-universe" meaning from the 原気/元気 forms remains, but now gets tied to the "health" ideas. When people hear "genki" today, they mostly think of positive energy, which includes things like courage, power, strength, pep, cheerfulness, and so on.

So, 元気 is still a pretty abstract concept, and its origin story doesn't make things any easier. We're going to go through the main ways to use genki, though, starting with genki as a state of being. From there, we'll imagine genki to be a living, breathing thing (a thing that you can do stuff to). And finally, we'll look at doing things "genki-ly," as it were.

Depending on your level of Japanese, some concepts will be very easy. They are basic. Other parts of your genki education may require a little more Japanese knowledge. In the end, though, you will have a much better understanding of genki no matter your level. At the very least, maybe we can get you to stop saying "o genki desu ka?" to every Japanese person you meet.

Okay, let's get genki!

Genki As Something You Can Be

If you've ever taken a Japanese class, you almost certainly learned this pattern:

- お元気ですか?

- How are you?

- 元気です。

- I'm well.

Despite the fact that this pattern is taught almost universally in every classroom, it's actually not all that common for a Japanese person to utter these exact words. It's similar to English, actually. Like when you meet your definitely human friend and greet them with "Hello, how are you?" Then they reply to you, a person who is also definitely human, with "I am fine, and you?" It makes sense, but it sounds like you're hiding some metal and silicon under your skin.

Still, this pattern is a great jumping off point for your genki education. It's a solid piece of knowledge you have in this abstract, nebulous cloud that is the meaning of genki. You're going to work off of it to get to more difficult—and useful—stuff.

First, let's talk about how to make this「お元気ですか? 元気です。」pattern sound a little more natural.

- 元気?

- How are you?

- 元気。

- I'm well.

Simply put, you can just say 元気 twice. One sounds like a question, the other a statement. "You good?" "I'm good."

Now that we have that out of the way, let's go back to 元気です. When you say this (or when you're saying 「元気」) you're essentially saying that you are genki. It's like another very common beginner-of-Japanese pattern you probably learned: [name]+です. For example, マミです means "I am Mami." A construction worker, a dog, and a mother are also things I can be. It just so happens in this case that I am genki and all that it embodies.

But if I can be genki, I can also not be genki. Here are a handful of sentences that all mean "I am not genki" / "I am not doing well." You don't need to learn every version below. I'm just providing them to show levels of formality, and because there is inconsistency in what negative-noun patterns get taught first in Japanese classrooms.

- 元気ではありません。

- I am not well. (formal)

- 元気じゃないです。

- I am not well. (formal)

- 元気じゃありません。

- I am not well. (formal)

- 元気じゃない。

- I'm not well. (casual)

Now, if you can not be genki, you can also have been genki in the past. Or not! As in "How have you been?" and "I've been well."

- お元気でしたか?

- How have you been? (formal)

- 元気でした。

- I have been well. (formal)

- 元気だった?

- How've you been? (casual)

- 元気だった。

- I've been good. (casual)

There's a different feeling between asking 元気ですか and 元気でしたか. 元気ですか is if you are asking how they are now. 元気でしたか is like asking how things have been between the last time you met and now ("How've you been?"). It's essentially the same thing in English, I think, so it shouldn't be too hard to get your mind around.

Finally, let's look at past-negatives. When you were not genki.

- 元気じゃなかったんです。

- I haven't been well. (formal)

- 元気じゃありませんでした。

- I have not been well. (formal)

- 元気ではありませんでした。

- I have not been well. (formal)

- 元気じゃなかった。

- I've not been well. (casual)

One note: while all those are grammatically correct and make sense, you won't hear native speakers saying「元気じゃない」or「元気じゃなかった。」(plus all of their levels of formality) very often. Instead, you would typically be specific about what's bringing you down, saying something like, "I'm a bit tired today."

If you think about it, most people do the same thing in English. It feels weird when someone answers "I'm not well" and then leaves it at that. In fact, instead of doing that, people tend to just lie and say "I'm good," even when they're not. It's basically the same in Japanese, too.

Although this might be a bit advanced for some of you, I'd like to go beyond the simple「お元気ですか? はい、元気です。」patterns in your textbooks. I've written example sentences of various ways you—or somebody else—can be genki.

- よお、元気?

- Hey. What's up?

- カナエは元気いっぱいだ。

- Kanae is full of energy.

- カナエはとても元気です。

- Kanae is very genki.

- カナエって、いつもめっちゃ元気だね。

- Kanae, you are always super genki, huh?

- カナエは元気そのものだ。

- Kanae is energy itself.

- こちらは相変わらず元気です。

- We are as good as ever.

- コウイチ子お婆さんはもうすぐ百歳になりますが、まだ元気です。

- Grandma Koichiko is almost one hundred years old, but still going strong.

- お陰さまで皆元気です。

- Thanks to you, we've been great.

Is 元気 Physical or Mental Health?

Unfortunately, this is just one of those "that's the way it is" language rules.

When translating 元気です to English, it generally becomes "I'm well" or "I'm good." No specific reference to whether it's mental or physical well-being. There's a reason for that, and it's not a good one: genki refers to both physical and mental states. Assuming you read about genki's history and etymology, you know why.

But what if you want to specify that your genki is physical? Or mental? Let's start with this incredibly unhelpful example sentence:

- 元気だけど、元気じゃない。

- I'm genki, but not genki.

When a Japanese person sees this, though, they would automatically assume it means "I'm physically genki, but not mentally genki." Here's the thing: you can't do it the other way around. You can't say「元気だけど、元気じゃない」to say you are sick / ill but in a good mood. Unfortunately, this is just one of those "that's the way it is" language rules. So, when you want to say your physical genki isn't doing well, but your mental genki is, you need to drop the genki and get specific.

- 熱はあるけど、元気です。

- I have a fever, but I'm genki.

In this case we are specifying that our physical ailment is a fever, but we're still (mentally) genki. Maybe you're still doing stuff, have energy, and/or in a good mood. Even though this is the case, I still recommend you rest.

- 健康だけど、元気じゃない。

- I'm healthy, but I'm not genki.

The word 健康 (けんこう) refers to your general physical health. It's a good "physical genki" replacement.

- 病気じゃないけど、元気でもない。

- I'm not sick, but I'm also not genki either.

Finally, we are using the word 病気 (びょうき), which means sickness / illness, to specify. In this case, we are not sick, but also not (mentally) genki.

As you can see, there's a lot of variety! But in cases like these, genki will usually default to how you feel in terms of your energy / mental feeling. When it's important to specify that your genki-ness is physical, you can do so with the above words and examples. I think these should cover most situations.

Alright, let's get back to being genki!

Becoming Genki

It's possible to not be genki, of course. But, some people are genki, too. That means there's a way to become genki! Although I can't tell you how to get there, I can tell you how to talk about it in Japanese.

The verb for "to become" is なる, and the pattern is xxになる. As in, 犬になる (to become a dog), 弁護士になる (to become a lawyer), and yes, 元気になる (to become genki). When you become genki, you go from a state without pep to a state with pep. You become happy. You become energetic. You become healthy. You know the drill. Genki has a lot of different meanings, so it could really be a lot of things. Use those context clues!

- マミはベーコンを食べると元気になる。

- Mami is rejuvenated when she eats bacon.

Notes: When she eats bacon, she becomes genki.

- もうすっかり元気になりました。

- I'm quite all right now.

Notes: It seems like someone wasn't feeling well before. Maybe they were lightheaded, sick, or depressed. But now they're better. They became genki.

- 元気になったみたいでよかった。

- I'm happy to see that you got better.

Notes: It's hard to tell whether this is about physical or mental genki. My feeling is physical, but it could be either. Once again, if this were a real conversation, we could figure it out from context.

- 早く元気になるといいね。

- I hope I'll / you'll feel better soon.

Notes: It sounds like someone can't control when they become genki again, which makes me think they're referring to an illness or injury. Or perhaps a devastating event (like the death of a loved one). They want to become genki again from their current state of not being genki.

- 早く元気になってくださいね。

- Get well soon!

Notes: This could either be illness / injury or mental feeling. It's not clear which, but I bet if you were there, you could figure it out with the power of context.

- 元気になれる歌を教えてあげるよ。

- I'm gonna teach you a song that makes you happy.

Notes: Clearly, this one is about mental genki. It's about a song that will let you become genki.

A 元気な Thing

If you can be genki, you can describe something as a genki thing. This basically works for any animate object, though it's most often used to describe genki people or categories of people.

- 元気な人

- A genki person

- ビエトは元気なヤクザです。

- Viet is a genki yakuza.

- 元気な子ども

- A genki child

The key is the 元気な+[noun] portion of each sentence, where the noun is ヤクザ, 人, and 子ども, respectively. Really, you can put any noun in there, as long as it's animate, alive, or close to it… though now we're hitting a gray area. You might be able to say the Earth or a robot is genki. But saying you have a genki computer (assuming you aren't reading this after our AI overlords have taken over) is a bit weird. The word genki, itself, just has a sort of living, vibrant feeling to it. A genki spork doesn't fit, no matter how grammatically correct it is.

Take a look at the following examples to get an idea of the variety of 元気な nouns you can talk about.

- コウイチは元気な宇宙人です。

- Koichi is a genki alien.

- 元気な老人

- A genki old person

- 元気な犬

- A genki dog

- 元気なヒマワリ

- A genki sunflower

- 元気な盛り

- The genki prime time of life

As you can see, there are quite a few things that can be genki, but they're all pretty animated.

Staying 元気

元気で is like saying "by way of genki."

As the great Dos Equisian philosopher once said: "Stay genki my friends." If you can be genki, you can stay genki.

To do that, just add the particle で to 元気. This particle does a lot. I won't even begin to explain it here (I'd go way over my word count). But, I will tell you really quick that one of its meanings is roughly "by way of." 元気で is like saying "by way of genki."

Let's take a look at three really common versions of the phrase "take care" in Japanese.

- 元気でね。

- Take care. (casual)

- 元気でな。

- Take care. (casual, masculine)

- お元気で。

- Take care. (polite)

Levels of formality and gendered language aside, these sentences mean the same thing. Essentially, you're saying "by way of genki… live your life." Sounds like something Yoda might say. More simply, you're telling someone to "take care."

Those sentences don't really specify what comes after the 元気で, though. You fill in the blank, and assume that blank just consists of life, the universe, and everything. You can specify something you do "by way of genki" if you want, though.

- 元気でいてね。

- Stay well. (casual)

Literally: Exist by way of genki.

- 元気でいてくれよ。

- Please stay healthy. (casual, masculine)

Literally: Exist by way of genki for me.

- お元気でいてくださいね。

- Please stay healthy. (polite)

Literally: Please exist by way of genki for me.

That いて in the 元気でいてs of the above sentences is いる. Existence. You're saying "by way of genki, exist," or "exist well / healthily." More simply translated: "stay healthy," "stay well," or "take care." The 元気で examples from before are omitting something, and… you guessed it, this is what they're probably omitting.

That being said, if you want to specify what comes after the 元気で, you should do so.

- 元気で暮らしています。

- I've been doing well.

Literally: "By way of genki, I've been living my life."

- 元気で過ごしています。

- I've been doing well.

Literally: "By way of genki, I'm spending (my) time."

- お母さんは元気でやっているよ。

- My mother is doing well.

Literally: "By way of genki my mother is doing (genki)."

With that, we've looked at all the ways you can be genki. There's going to be plenty of overlap in the next sections, but now you should have some understanding of the malleability of genki and its meanings. With those ideas in mind, let's take a look at genki as a thing you can do something with.

Genki as a Thing That You Can Do Something With

First you were genki. Now it's time to change how you think of genki. What if it were a thing, like a genki dama from Dragon Ball? What if you could give and receive genki? What if it could disappear? What if… you could excrete it?

Don't worry, we will cover all of those and more. So, close your eyes and visualize genki as a thing. A noun. Now that you have that image in your mind, we can start doing things to it and moving it around.

Having & Not Having Genki

If genki is a thing, it's something one can have. Or not have! The most common patterns around this are 元気がある and 元気がない.

- 元気がある。

- There is genki / To have genki.

In Japanese, ある means "to exist" or "to have." Since 元気 is something you hold inside, saying 元気がある means whoever you're talking about has that energy.

- 元気がない。

- There is no genki / To not have genki.

If genki is a thing, it's something one can have. Or not have! The most common patterns around this are 元気がある and 元気がない.

ない is the negative form of ある, so saying 元気がない means the person you're talking about doesn't have that energy or spirit. Perhaps they're sad or depressed. Or they just don't have much pep or spirit.

Actually, 元気です and 元気がある are pretty similar and sometimes interchangeable. But there is one big difference. 元気がある is better for other people. The reason is because it's not so assertive. When you say someone has genki, it could be a little bit or a lot. Saying someone is genki is a bit presumptuous. Who are you to know if they are genki or not?

- コウイチはいつも元気がある。

- Koichi always has energy.

- 今日のビエトは元気がない。

- Viet looks blue today.

- マイケルはなんだか元気がありません。

- Michael is looking somewhat unwell today.

Okay, so you now know how to have genki, but what if you have genki for doing something? The pattern for that is [verb]+元気. Specifically, that verb should be in dictionary form, for example: 食べる元気 (genki to eat). This means you have a lot of energy, excitement, pep, vigor, etc. to do whatever you're doing.

- 料理をする元気

- Excited to cook

料理をする is "cooking," and by adding 元気 you are essentially saying you have "cooking genki." Pep, energy, and/or excitement to cook.

Here's another situation. Michael has been out all night. But, when he gets home he turns on the ol' Famicom to play Mario. He's tired… but he still has genki for Mario. Considering his late night, it's a bit unexpected he would have the energy to do anything. But for his bff Mario… he still has genki. How might you express this?

- マリオをプレイする元気

- Excited to play Mario

Now let's take a look at some more [verb]+genki examples.

- 私はみんなと話をする元気がなかった。

- I didn't have energy to talk with people.

- 失恋のショックで、食べる元気もありませんでした。

- I failed in love and was too heartbroken to even eat anything.

- 元気じゃないけど、食べる元気ならある。

- I'm not feeling well, but I can eat.

That last one was too meta for me. Let's take a look at other ways you can do stuff with genki.

Getting the 元気 Out

Even though it's an intangible concept, 元気 energy is something we innately understand as humans. It feels like a measurable thing that we can imagine. Sometimes it bursts out, making you a superhuman 元気 machine! At other times, your genki tank is empty, and you can barely squeeze a drop out. In situations like these, you might use:

- 元気が 出る。

- Genki comes out.

- 元気を 出す。

- Get the genki out.

The difference between them is that one is a transitive verb and the other is intransitive. These terms are huge concepts in Japanese—too big for this article. To understand them fully, hop on over to Tofugu's guide on transitive / intransitive verbs. Essentially, though, 元気が出る is when genki comes out on its own and 元気を出す is when you're the one making the genki come out.

As for what these sentences actually mean, I think a clue actually comes from genki's etymology. Remember how there was a version of genki where it meant "decrease energy" (減気) and people were trying to get the bad energy out of themselves to achieve that yin yang balance? Think of it in that sense. When genki comes out (元気が出る), it means someone feels good, not that you're losing your good feeling. It's a positive thing for your genki to come out.

A Gross Tip from Koichi: I've always imagined 元気が出る and 元気を出す as rainbows coming out of people's mouths. As in, they have so much genki that it's coming out in the form of rainbow barf. When somebody 元気を出すs (i.e. when they push their genki out), I see them projectile vomiting genki rainbows all over the place. Like, in a good way. It goes against the original etymology, but we arrive at the same finish line, and I think it's easier to wrap one's mind around. It's more consistent with the rest of the ways to use genki.

With that beautiful imagery in mind, let's look at some examples that use 出る/出す.

- ビールを飲んだたら元気が出た。

- I felt refreshed with a bottle of beer.

Literally: After drinking beer, genki came out.

- クリステンの話を聞いて元気が出ました。

- Kristen's story cheered me up.

Literally: I heard Kristen's story and genki came out (of me).

- そんなに簡単に元気は出ないよ。

- It's not that easy to pick myself up.

Literally: Genki won't come out of me that easily.

- だんだん元気が出てきた気がする。

- I feel like I'm slowly feeling better.

Literally: I feel like more and more genki is coming out (of me).

Now let's look at 元気を出す, which is often translated as "to gather one's strength," "to take heart," "to cheer up," or as Koichi might say, "projectile vomit your genki all over anything that gets in your way and be genki." You know it's a good translation when it uses the word you're trying to define (genki) not once, but twice.

- がんばって元気を出すよ。

- I'll try my best to keep my spirits up.

Literally: I'll persevere and get my genki out.

- 元気を出すためには、ベーコンが必要です。

- I need bacon to regain my strength.

Literally: In order to get my genki out, bacon is important.

- 元気を出してください。

- Please cheer up. (polite)

Literally: Please get your genki out.

- 元気を出して!

- Cheer up! (casual)

Literally: Get your genki out!

Even though it's an intangible concept, 元気 energy is something we innately understand as humans. It feels like a measurable thing that we can imagine.

You can say this last one to a Japanese kid crying about something trivial. Like, "c'mon, get your genki out, you spoiled brat. Did you actually think the One Piece treasure would be anything other than a treasure box with a note inside that has 'nakama' written on it?"

Anyway, in these situations you're mustering up your genki when you have none. Or you're telling someone else to do it.

But, sometimes it's only temporary; deep down, you're still sad or worn out. For cases like these, I wanted to show you the concept of 空元気 (からげんき), or "empty energy." Sometimes it's translated as "courage," because often courageous people stand up and fight in spite of their fear, exhaustion, and empty genki tank.

There's a long ways to go, still, so you may have to do just that.

When Genki Disappears

If "genki" is a thing you can have, not have, and even barf out, it stands to reason that it can disappear, too. Sometimes when you're feeling good, something comes along and steals it away from you—perhaps you step in dog poop (or human poop, honestly it's hard to tell sometimes), and that 元気 spirit abruptly swirls down the drain.

In this case, and many others, you might say your genki disappears.

- 元気が 無くなる。

- The genki is missing / gone.

無くなる is used when you lose something. You have the feeling that something disappeared, not that it went away and you know where it is.

- カナエちゃんが元気がないと、僕も元気が無くなる。

- If Kanae feels sad, I will feel sad too.

Literally: If Kanae doesn't have genki, I will also lose my genki.

You can also use 無くす (to lose something) in a similar way.

- その犬は、怒られて元気を無くした。

- That dog lost his pep after being scolded.

Literally: That dog was scolded and lost its genki.

But hey, if you lose your genki you should try to get it back. When it finally does return, you could say 元気を取り戻す (げんきをとりもどす). This is usually translated as "to recover one's spirits" or "to pull oneself together."

Genki Given, Genki Received

You can give and receive genki too. When you do this, essentially you are saying that you made somebody feel good (you gave them genki) or that somebody made you feel good (you received genki).

- ジャマルの歌声に元気をもらった。

- I gained energy from Jamal's singing.

Literally: I received genki from Jamal's singing.

- 辛い時は、いつもこのダリンの人形を見て、元気をもらうんです。

- Whenever I feel depressed, I look at this Darin doll and gain strength.

Literally: When I'm sad, I always look at this Darin Doll and I receive genki (from it).

So that's about receiving genki. What about giving genki to someone? It's a little bit like the 元気がある and 元気です pattern. You shouldn't say that you gave genki to someone because who are you to say you actually gave them genki? You don't know how they feel! I guess you could say it, but it's a little weird and egotistical, I think. Stick to receiving genki, and just do your best to give genki to others without worrying about if they received it or not.

Do Things "Genki-ly"

So far you've learned that you can be genki and that you can do things with genki. Now, let's look at doing things… genki-ly. That makes sense, right?

Doing Genki-ly

If you add に to 元気 you get 元気に. You're essentially changing "genki" to "genki-ly." We're going to look at this pattern with してる, which means "doing." Doing + Genki-ly comes out to "doing genki-ly." In other words, 元気にしてる means "doing well."

- 元気にしてる?

- How've you been doing?

- 元気にしてる。

- I've been doing well.

Here are some more formal forms for you, just in case:

- お元気にしていますか?

- Are you doing well?

- 元気にしています。

- I've been doing well.

These are pretty similar to the 元気ですか and 元気です patterns. 元気ですか is "how are you?" whereas 元気にしてますか is "How are you doing?" 元気です is "I'm well," but 元気にしています is "I'm doing well." Subtle differences, but when you get down to it, they're basically the same. That applies to past and negative forms of している too.

- お元気にしていましたか?

- How have you been doing? (formal)

- 元気にしていました。

- I have been doing well. (formal)

- 元気にしてた?

- How've you been? (casual)

- 元気にしてた。

- I've been doing well. (casual)

These three were similar to the 元気でしたか and 元気でした patterns you learned earlier. Instead of asking "Were you well?" you're asking "Were you doing well?" Then your answer is "I was doing well."

- 元気にしていません。

- I have not been doing well. (formal)

- 元気にしてない。

- I've not been doing well. (casual)

- 元気にしていませんでした。

- I have not been doing well. (formal)

- 元気にしてなかった。

- I've not been doing well. (casual)

Let's check some of these out in actual example sentences.

- みんな元気にしてる?

- How's everybody doing?

- うん。こっちは相変わらず元気にしてるよー。

- Yep. We've been doing as well as ever.

- コウイチお爺さん、もうすぐ百歳になるけど、まだまだ元気にしてるよ。

- Grandpa Koichi is almost one hundred years old, but still doing well.

Ah! Most of these felt like greeting set phrases, but this last example sentence was a bit more general. You're not talking about yourself or asking someone how they're doing. Instead, you're talking about a third party, grandpa Koichi. Let's find out what's going on here.

Do Something Genki-ly

If you can be "doing genki-ly," can you "do something genki-ly?" As in, 元気に[verb]? Well, we did see an example sentence doing just that. One more time, in case scrolling up 50px is too much for you.

- コウイチお爺さん、もうすぐ百歳になるけど、まだまだ元気にしてるよ。

- Grandpa Koichi is almost one hundred years old, but still doing well.

That begs the question, can you use the 元気に[verb] pattern with other verbs besides してる? Are 元気に食べる (to eat genki-ly), 元気に歩いてる (walking genki-ly), and 元気に話してる (talking genki-ly) valid? The answer is yes… and no. And it all comes back to Grandpa Koichi.

If you say someone is doing something genki-ly, it feels like you're saying "they are doing xyz genki-ly (but it was unexpected)." Maybe someone is very sick, but they are eating as if they weren't sick. Then you could say they are 元気に食べてる. Or, perhaps someone has had trouble speaking for a long time due to illness, but now they're talking (even if it's a normal or less-than-normal amount of talking). Then you could say they are 元気に話してる. There's this implication that they weren't able to do these things genki-ly before, or that it was unexpected of them to do these things genki-ly.

That brings us back to Grandpa Koichi. He's an old, old man. So, it's unexpected that he's doing (してる) anything genki-ly. Thus, it makes sense to use this pattern here.

Anyways, 元気に[verb] patterns outside of 元気にしてる greeting do exist—and you might even be able to use them outside of hospitals sometimes—but in general, it has a feeling of unexpected genki-ness in the face of something negative.

Doing Something Super Genki-ly

In the previous section, I mentioned that 元気に[verb] kind of has the feeling that someone is more genki than they ought to be, considering the situation. So, when you want to say someone is doing something genki-ly in a normal, not hospital situation, you ought say they are being SUPER genki. To do this, just replace the に with よく, giving you 元気よく[verb].

Besides the intensity (seriously, we're talking super genki) there is one other difference.

- 元気に can be used to describe actions of any duration.

- 元気よく can only be used to describe actions that last for a short while.

For example, you can say:

- 元気に 言う ✅

- 元気よく 言う ✅

(Because you can talk for a short time, or you can chat someone's ear off, monopolizing their time for the entire dinner party!)

You can also say:

- 元気に 歌う ✅

- 元気よく 歌う ✅

(Because you can sing for a little while, or you can belt out a whole opera!)

But if you try to say:

- 元気に 育つ ✅

-

元気よく 育つ ❌

- 元気に 暮らす ✅

- 元気よく 暮らす ❌

Your state of being from the last time someone saw you couldn't have been "super 元気" for days on end. It's impossible!

These sentences don't work with 元気よく, because "to grow up" and "to live" take a long time.

When you think about it, this makes sense: you can be super 元気 while singing a song, or even when singing an entire opera. But to stay at an extreme level of 元気 forever… well, that's too much. Everyone needs to switch off and rest sometimes.

This distinction explains why the "How have you been?" sentences in the above sections used 元気に. Your state of being from the last time someone saw you couldn't have been "super 元気" for days on end. It's impossible!

That said, I'd like to take a moment to contradict myself. 😛 Some Japanese speakers do use 元気よく育つ and 元気よく暮らす, because… well, language is a dynamic medium and people can do what they want with it. But it's relatively uncommon to use 元気よく with long-term activities. If you hear or see someone doing it, they're not wrong—they're just in the minority.

Other 元気 Terms

We're reaching the end of our genki journey. Before tying things up, I'd like to introduce you to a few genki-related set phrases. Some are more useful than others, but let's take a look for fun.

元気印

元気印 (げんきじるし) is made up of two words: 元気 and 印 (seal, symbol, mark), and is used to describe someone known for being 元気—as in, being 元気 is their trademark.

- トーフグは元気印だ。

- Tofugu is known for being genki.

元気百倍

元気百倍 (げんきひゃくばい) literally means "100x 元気." It's used to describe someone or something that's ridiculously energetic.

元気百倍 is used by famed anime character Anpanman, whose punch has 元気百倍 (100x genki) power.

- 元気百倍、アンパーンチ!

- 100 times genki An-punch!

元気もりもり

元気もりもり is similar to 元気百倍. もりもり is a Japanese onomatopoeia that describes well-developed muscles, so it's often translated as "energetic," "vigorous," or "full of vitality."

- キン肉マンはいつも元気もりもりだ。

- Kinnikuman is always full of vitality.

元気が取り柄

取り柄 (とりえ) means a "merit" or a "strong point," so 元気が取り柄 is translated as having the merit of being 元気. For example, you can say:

- トーフグは元気が取り柄だ。

- Tofugu has the merit of being genki.

Nice! That is one of our merits!

But, it can also be used in the form of a put-down. It wouldn't be uncommon to hear:

- トーフグは元気だけが取り柄だ。

- Tofugu's only merit is being genki.

…which basically means Tofugu's only good point is its being 元気. That's all Tofugu has going for it.

(Hey! That's not true!)

元気づける

元気づける is a combination of 元気 and つける (which means "to put on" or "to attach.") So 元気づける is used when you "put 元気 on" someone. By putting genki on someone, you're presumably giving them genki and encouraging them.

- 私はビエトの歌声に元気づけられました。

- I was encouraged by Viet's singing voice.

- みんなでマイケルを元気づけよう。

- Let's cheer Michael up!

Literally: Let's all stick some genki on Michael.

If someone is not 元気, please 元気づけてあげてね! Scoop the genki out of your body and wipe it on their chest, or something.

Download the Genki Example Sentences

You've arrived at the end of today's Japanese word journey. Congratulations! Can you feel the knowledge-plants sprouting from your head yet? At this point you probably don't have much genki left, but that's okay. It means you've worked hard.

Speaking of which, we put together a spreadsheet with all the example sentences from this article. You can upload them to your SRS of choice for study. If you are a Tofugu email subscriber, you'll get it in your inbox. If not, just subscribe here to get the file. We'll tell you about new language articles, send you Japanese lessons (which are basically mini Tofugu articles), and do our best to never send you garbage spam. That would make us all a little less genki.

Now, please rest up and get your genki back. We'll see you again when genki wells up inside of you, eventually seeping from every swollen pore of your body. 元気でね♡