だ and です are everywhere in Japanese, and getting to grips with them is essential for any Japanese learner. Despite being such basic building blocks, their use in real-life Japanese can be frustratingly different from their textbook explanations. For example, you may have learned that だ and です are two variants of the same word and that we choose between them based on whether the person we're talking to has a higher or lower status than us. In other words, です is used when we want to be polite and だ is used to be casual. But real-life Japanese significantly deviates from this often-taught standard.

Textbook rules for です and だ can leave us scratching our heads when we hear native speakers of Japanese breaking the rules left, right, and center. This is a huge problem for language learners; how can you learn to use a grammar structure if the rules you study are full of holes and exceptions?

In order to get to the bottom of です and だ, we spent a good chunk of time diving into dense linguistics research and discovered some pretty interesting ways of looking at these words. As it turns out, the conceptual distinction between です and だ comes down to the direction of the message. In other words, if the message is self-directed and your main purpose is expressing your thoughts or feelings, then だ is your ticket. If your message is directed toward others and you intend to present information in a socially aware manner, then です is probably preferred.

Think of this article as a roadmap to navigate your way around all the intricate nuances that です and だ convey in real-life contexts. To help you understand, we're going to take a bold step away from traditional grammar-rule-type explanations you'll find in textbooks. Instead, we will lay out the conceptual meanings of です and だ, so you can use them to better express yourself in Japanese and add flavor to both your spoken and written communication.

- Conceptualizing です and だ in Speech

- Nuances of だ in Spoken Japanese

- Nuances of です in Spoken Japanese

- Conceptualizing です and だ in Writing

- Traditional Writing Styles and Rules

- Genres with Consistent Style

- Genres with Mixed Writing Style

- だ Takeaway

Prerequisites: This article assumes you already know hiragana and katakana. If you need to brush up, have a look at our Ultimate Hiragana Guide and Ultimate Katakana Guide. This article will talk about the nuances of だ and です, so beginners can read it too, but to get the most out of it, you'll need an intermediate understanding of Japanese.

Before you read on: we recorded a two-part podcast series about だ and です. In it, we answered questions about だ and です from Japanese learners. Make sure to check it out after reading this article!

And if you haven't, you can subscribe to the Tofugu podcast. After subscribing, you can save the episode for later to review what you're about to read.

Conceptualizing です and だ in Speech

We'll begin our learning journey by comparing how です and だ add meaning to a spoken statement in Japanese. This section will feel very abstract, so we'll use images to make the ideas we introduce clearer. To start, take a look at the image of だ below.

As you can see, the speaker is surrounded by a bubble, which we will call "personal space." When a speaker makes a statement ending in だ, the statement stays within their personal space and thus is made without (much) attention paid to the larger, social world. In other words, だ statements allow a speaker to step outside of social expectations and focus on self-expression.

Now let's turn our attention to the concept that です represents. In the image above, you can see that the speaker's statement leaves their personal space bubble and reaches toward another person. This shows that the speaker's focus is on the listener and the social situation that they are in when they are speaking. The fact that the statement travels beyond the speaker's personal space emphasizes the line that separates the speaker and the listener—the distance between them. This distance raises the level of politeness, which is why we think of です as being more polite.

At this point, our concepts of です and だ might feel a bit fuzzy or vague, but not to worry! We want the framework to be applicable across all contexts, so that as you encounter individual instances of です or だ, you'll be able to apply the concept and understand how it affects the meaning of the sentence overall. Throughout this article, we will refer back to these concepts as we walk you through a range of contexts. As you read, your concept of です and だ will begin to sharpen and, by the end of this article, it should serve as a great tool to aid you in your ability to understand and use Japanese.

Nuances of だ in Spoken Japanese

When we make だ statements, we are stepping away from the need to perform in a socially calculated way, and instead we emphasize our personal thoughts and feelings. In other words, だ statements allow us to avoid considering our relative social status compared to our listeners' because the statement is conceptually staying inside our personal space. In the safety of our bubble, だ statements do not necessarily require a response. This enables us to devote all of our attention to self-expression.

だ statements are made with more attention paid to what we have to say rather than our relationship with the listener.

That said, statements made in our personal space are not heard only by ourselves; there are plenty of reasons why a listener might be considered to be inside your bubble, or people who are outside of your personal space might hear your だ statement. The major takeaway here is that だ statements are made with more attention paid to what we have to say rather than our relationship with the listener. To show you what we mean by this, in the following sections we will take a look at the various ways in which だ adds an expressive feeling to statements in various contexts.

だ for Emphatic Self-Expression

Statements that end in だ can be used to express thoughts and feelings that arise suddenly or powerfully within us. These kinds of statements are self-directed, and thus we can imagine that they remain inside our personal space bubbles when we say them. Contrary to what you may have learned in textbooks, だ is commonly used to express your inner state when speaking in the presence of someone to whom you'd usually use a more polite speech style like です and ます. This is because your use of だ communicates that the purpose of the statement is self-expression and not actually directed at the listener, even if they are within earshot. Let's examine a few variations on this concept.

Imagine you are sitting in your favorite ramen shop. You just finished your meal and are happily patting your noodle-filled belly. As you stand up to leave, you see a mouse skitter across the floor into the kitchen. Filled with a sense of sudden surprise, and perhaps disgust, you might say:

- うわ、ネズミだ!

- Ew, a mouse!

Whether you're eating with your boss (whom you usually address with the polite です・ます speech style) or you're eating all by yourself, this would be an appropriate expression. More than anything, the intention of such an utterance is to express the feeling of surprise that rises up within you at the sight of the mouse.

However, self-expressive だ statements do not necessarily need to be triggered by a surprising event, such as a mouse sighting. Imagine you are happily skipping along on your way to school, when it suddenly dawns on you that you have a kanji test that afternoon. To express your feeling about this sudden remembrance, you could say:

- やばい!テストだ!

- Oh no! There's a test!

The previous two examples carried a sense of sudden recollection or surprise, but だ statements are just as effectively used to express strong emotional reactions to events or situations, even if they are expected.

Since you forgot to study for your kanji test, it's no surprise that you got a lower score than you wanted. When your teacher hands you back your test, and you see your failing grade, you might mutter to yourself:

- ああ、また失敗した。私ほんとバカだ。

- Ah, I failed again. I'm so stupid!

Don't be so hard on yourself! At least you formed an appropriate statement to emphasize your disappointment using だ! Next time, after studying harder, you might ace your kanji test and express a positive emotion instead:

- やった!私天才だ!

- Yay! I'm a genius!

To wrap up this section, take a look at the following examples. Can you tell if the だ emphasizes surprise, sudden remembrance, or strong emotions? Make sure to consider the context and listen to the audio to hear the intonation as well.

You're on a golf course, and you almost have your ball in the hole, but every time you putt, you just narrowly miss the hole.

- もうむりだ!

- I can't do this anymore.

You're on a long drive and have gotten a bit lost. You pass the top of a hill and see the ocean spread out in front of you.

- 海だ!

- The ocean!

You're at home, getting ready for bed. You catch a glimpse of your calendar and say:

- あ、今日お母さんの誕生日だ!

- Oh, today is my mom's birthday!

だ for Sounding the Alarm

There are some cases where it is not clear whether a だ statement should be considered self-directed or directed at others. For these examples, we think it is useful to imagine that the speaker's personal space bubble has expanded to include the listeners inside of it. Let's take a look at an example to clarify this point.

- 火事だ!

- Fire!

In the event of a fire, it's more important to alert the people around you of the danger than it is to construct sentences with appropriate politeness levels. With its emotional, forceful feeling, だ catches people's attention and alerts them to the urgency of the statement. Of course, the speaker's tone of voice plays a huge role in this too! While the statement is intended to alert others of danger, it is still not an interactional statement. In other words, the speaker isn't trying to strike up a polite conversation about the fire, they just want everyone to get the heck out of there!

At its core, this use of だ to warn others is just a variation of the same concept we discussed before. Remember the mouse in the ramen shop? If we reimagine the context in a very slightly different way, it could be considered an example of "sounding the alarm" as well:

- うわ、ネズミだ!

- Ew, a mouse!

If we imagine that you had muttered this statement to yourself when we described it as self-expressive, you could also have shouted it out to alert others of the rodent infestation. Or perhaps it is a blend of the two—in a moment of sudden terror, you might have unintentionally shouted the statement, which of course would also alert the other patrons. You can see how context-specific and dynamic language is, yet the basic concept that だ is more expressive than interactional remains the same.

However, this type of だ statement is not necessarily always used for good, it can also be used for evil. Imagine you are at the bank, minding your own business, when an armed robber enters the building. Just like in the movies, he announces to everyone in the bank:

- 強盗だ!

- This is a stick up!

In this case, the speaker (i.e., the robber) clearly is not concerned with being socially aware in how he forms his statement. I mean, he's robbing a bank! Just like in the previous example, the speaker is only interested in disseminating information to everyone in the bank, and he couldn't care less what anyone has to say or think about it. In this way, the statement is directed at others but intended only to meet the speaker's own purposes. In addition to "sounding the alarm," so to speak, this statement is also menacing; due to the fact that the message implies danger to the listeners, だ emphasizes this threatening tone. This brings us to our next conceptual meaning of だ statements: to indicate an invasion of personal space.

だ for Invading Personal Space

When だ statements that carry a negative emotion or message are directed at a specific listener, だ adds an aggressive and assertive feeling. In this case, the listener may feel surprised, affronted, or threatened by the statement. For this reason, we refer to this use of だ as "invasive." That is, the statement invades the personal space of the listener, as you can see represented in the image above by the boxing-glove speech bubble.

This will probably be much clearer after an example. If someone has told me something that is not true, I might cry out:

- うそだ!

- That's a lie!

While this statement is clearly motivated by the actions of a particular person, the use of だ suggests that the statement is not intended to engage the listener in discussion. While it is directed at the speaker in the sense that it is intended to have an impact, it is stripped of all feelings of social responsibility or concern for the other person's point of view. The purpose is to express the speaker's outrage, not to start a conversation. The one-sided nature of this statement is what gives it an assertive, or even confrontational, feeling.

Although the statement is one-sided, it clearly still has an effect on the listener. Invasive だ statements can be used to invade a listener's personal space, similar to the way someone might stand intimidatingly close to another during an argument. This idea is illustrated above with the boxing-glove speech bubble entering the listener's personal space bubble. This use of だ is quite confrontational, so if you choose to use it, remember that it could create quite a stir. It is often associated with masculine speech but is used across the gender spectrum when someone is enraged.

Let's examine a few more examples of invasive だ.

- 俺たちはもうおしまいだ!

- We are done! (Our relationship is over.)

- なんだこの点数は?よし、今から勉強だ!

- What the heck is this score? You must study starting right now!

- 犯人は誰だ?

- Who's the culprit?

Based on what we've discussed up to this point, you might wonder if だ always carries an emotional, alarming, or assertive nuance when used in conversation. In the next section, we will introduce a way to use だ as a communicative tool to help you talk with your friends in a more friendly and interactive way.

だ in Casual Conversation

While the uses of だ we've discussed thus far seem to be directed at the speaker themselves, there are also cases where we use だ statements that are clearly directed at others. In these cases, だ is used because the listener is considered close enough to the speaker that their relative social statuses are not relevant or worth paying attention to by using です. Perhaps you are speaking to a friend, family member, or a friendly first-name-basis type of acquaintance. In these cases, we can imagine that the speaker and listener's personal space bubbles overlap like a Venn diagram, and an entire conversation can take place within their shared personal space.

When だ is used in casual conversations, it is frequently paired with conversational particles like よ and ね. Remember that when だ is used alone it can convey a feeling of strong emotion? Well, our particle friends help to make the statement sound softer and more interactional. Let's look at one real life situation where these particles are used in conversations. Imagine a situation where your friend is reading a comic book after school in your classroom, and you kindly inform him that there will be an exam tomorrow.

- A: 明日テストだよ。

- A: Hey, we have an exam tomorrow.

- B: え!?

- B: What!?

- A: 今日は徹夜だね。

- A: It's gonna be an all-nighter for you.

In the sentences above, the inclusion of particles helps the listeners know that the speaker is directing the statement toward them, and it is appropriate to respond. For example, by saying 明日テストだよ, you are reminding the listener of the test. If this is stated without the particle よ, this would sound more like a だ statement intended to express the speaker's sudden remembrance of the test. Similarly, saying 徹夜だね allows the speaker to show her empathy while suggesting the listener should study all night. Without the ね, this sentence would sound more like a strong command.

Nuances of です in Spoken Japanese

Now that we've covered the ins and outs of だ, let's switch our focus back to です. To begin, let's summarize what we have learned so far. だ statements are directed at the speaker rather than the listener and serve to communicate self-expression. They are used to convey emotions, among other things. On the other hand, です is used to direct a statement at a listener, showing the speaker's awareness of them.

Remember the conceptual image of です we introduced in the beginning of this article? In the picture, the speaker's statement is shaped like an arrow, which points directly at the listener. This represents the speaker's awareness of the listener, and the fact that it reaches out of the speaker's personal space bubble toward the listener emphasizes the line that separates the speaker and listener, which consequently raises the feeling of politeness.

This is why we almost always use です to talk to strangers or people we've just met, regardless of their age or social status. When there is distance between the speaker and the listener, we tend to use polite forms, like です. When it comes to conversations with acquaintances, however, the choice of speech style can be more than a simple decision because of the different nuances it creates. In the following sections, we will examine how distance plays a role in these different nuanced uses of です.

です for Creating Distance

- タメ口

- casual talk; frank, unreserved speech; peer language

As you already know, using です increases the distance between people, which results in their relationship feeling more formal. です is part of the "polite speech style" in Japanese, along with the ます form of verbs. This stands in opposition to the "casual speech style," which だ is considered to be a part of. Let's dig into the cultural side of people's choice of speech style. Even though using polite speech style, such as です, with someone older than you or in a higher social position than you is a rule of thumb in Japanese society, you will see people shift their speech style from polite to casual, even while in conversation with the same person. So why do people break the rules? Let's examine some situations in which this shift in speech style occurs.

Imagine that you are talking with your senpai at work. He might offer you permission to use タメ口. The word タメ口 consists of ため (equal) and くち (mouth), and is pronounced as ためぐち. As the word suggests, using it indicates that the speaker and listener have equal status.

We wanted to know how common this kind of invitation to use タメ口 really is, so we asked around to find out. More than two-thirds of the people we talked to said they have been asked to use casual speech by their senpai at school or in their workplace. Many of them also said that they gradually shift from polite speech to casual speech rather than changing their speech style right away.

If someone you know suggests you use casual speech, you might want to respond by saying something polite, such as「そうですか」or「いいんですか?」before you start using タメ口. This will make you sound humble and probably endear you to the other person.

マミあの、これなんの 書類ですか?

MamiExcuse me. Could you tell me what these documents are for?

コウイチ 敬語じゃなくていいよ。 堅苦しいし タメ口で話そう。

Koichi Mami, you don't have to speak so politely. It feels too formal. Let's talk more casually.

マミ そうですか?わかりました。じゃあ…そうするね。

Mami Oh, really? I see. Okay…I'll do that then.

If someone asks you to use タメ口, it is likely that the person wants to be friends with you. Or タメ口 can also be a sign of romantic interest. Depending on the situation and the person who is asking you to be more casual with them, you have the choice whether or not to reduce your social distance with them. In fact, more than half of the people we asked about their タメ口 experiences said that they tend to reject this kind of offer. This shows some people believe using タメ口 is one way to get closer with people, while other people feel uncomfortable about reducing the social distance.

Between people who are roughly the same age, it is common to gradually shift from polite style to タメ口 without asking one another for permission. There are also situations where people mix casual and polite speech styles from the very first time they meet. Good examples of this are 合コン (group dating parties), 新歓 (welcome parties for college freshmen), or other situations where there is an underlying consensus that people are there to get closer with one another. If the goal of the relationship is to be friends, it makes sense to start off on more casual footing.

As you can see, the way Japanese people use polite speech is closely related to their desire to regulate social distance.

です for Emphasizing Sarcasm

So far, we have talked about situations where you use casual speech styles with someone who is older than you or in a higher social position than you. When you use polite speech style with your close friends or family members, what impact do you think this has on your communication with them? Remember that using です creates distance between the speaker and the listener. When doing this with someone who is usually in your personal space bubble, the listener will feel ejected from the bubble, which can have a comedic, sarcastic effect but can also be perceived as rude or hurtful. Let's explore how this works in real life situations.

Imagine a situation where you have a boyfriend who is bragging about getting a whole lot of chocolates from his colleagues on Valentine's Day. Instead of using your energy to complain about his lack of sensitivity, you can say the following sentence, keeping the tone of your voice low for effect.

- へー、良かったですねー。

- Oh, good for you.

Saying this in a casual speech form would still communicate your true thoughts, which is that you're not happy about what he told you, if you manipulate the tone of your voice and facial expressions to show sarcasm. But the addition of です, makes your boyfriend feel you are creating distance between the two of you, and this makes your statement sound even colder. Remember, です emphasizes distance and creates certain nuances only when you use it with someone who you normally talk to in casual speech style.

Let's look at another example. Say your friend tapped you on the shoulder to show you a tall tower of Cheerios that they just made. They want you to share in their glory, but you are underwhelmed.

見て、できた!チェリオタワー!

Look! I built a Cheerio tower!

- はいはい、すごいですね〜。

- Okay, okay. That's great.

Again, you can create a sarcastic tone by changing your voice quality and facial expression. Saying this with です, emphasizes the fact that you are actually not impressed by the tower. This can also be a friendly joke since you sound like you're imitating an elementary school teacher giving a compliment to a child. This point will be discussed more in the next section.

If you're not careful, however, this sarcasm can be interpreted as being condescending and rude. For example, imagine you are in a heated tennis match and your opponent says to you:

- あれ、疲れた?さっきまでの元気はどこですか?

- Ah, tired? What happened to all that energy you had just now?

Saying this without ですか is still mean, but including ですか emphasizes the fact that there is suddenly distance between you and your opponent. This distance makes the listener feel they are looked down upon.

This kind of statement might remind you of anime characters that use polite speech during a battle or sports match. For example, Frieza from Dragon Ball uses polite speech on a regular basis, even during battles, so as to present himself as superior to his opponent. He changes his speech style to plain form, however, when he gets into trouble or loses a battle. In this way, the manga writer effectively shows a shift in the character's energy and mental state, simply by switching between だ and です.

By now, we hope you can see that your choice of speech style is associated with how you want to present yourself in relation to the person you're speaking to. In the following section, we will take this even further by showing you how you can present a different "version" of yourself by switching speech style.

です for Stepping into a Different Social Role

We've talked about how です creates distance between speakers and listeners, resulting in different nuances in communication. Another way this distance affects our communication is that it allows speakers to step into a different social role. What do we mean by a "different social role?" Well, in life we wear many different "hats," and we can use the way we speak to indicate which hat we are wearing at a given moment.

Let's use the example of elementary school teachers to clarify this point. In Japanese schools, teachers typically use polite speech style to address their classes as a whole. By emphasizing their role as a teacher using polite speech, they can keep their students aware of the fact that they are in school where kids have to learn certain social rules and manners.

There are conditions, however, where teachers change their speech style in the middle of what they are saying. What motivates their choice of one speech style over the other is how they want to present themselves within the narrative of a given moment. Let's examine an example conversation between a teacher and his students.

先生 今日の日直誰ですか。

Teacher Who's on duty today?

森 佐藤くんです。

Mori It's Satō.

先生 黒板に名前書き忘れてるぞ、佐藤。ちゃんと書いとけよ。

Teacher You didn't write your name down on the blackboard, Satō. Do it later.

佐藤 あ。はい。

Satō Oh, okay.

先生 忘れんなよ。はい、じゃあ、朝の会始めましょう。

Teacher Don't forget. Okay, anyway, let's start the morning meeting.

As you can see, teachers use polite speech style to address the whole class when talking about something that is relevant to everyone. When they talk to a specific student about something that is relevant only to that student, they are more likely to use casual speech. This is because what they say is more or less personal when they address particular students. When they address the whole class however, teachers tend to use です to show that they are now engaged in a social activity they are responsible for. In other words, teachers use です to signal that their focus is on the class, and they are well aware of their role as a teacher.

Trying out the Concepts in Action

Taking everything you've learned so far about how です and だ affect the meaning of spoken Japanese, let's look at one final example and see how the concepts apply. We'll be drawing from all the previous sections, so think of this as a mini-review. Here goes!

Imagine you're watching the Nichihamu baseball team play a game at the Sapporo Dome. Now that you've read this article, you're becoming more aware of how だ and です are used in real life, and you notice that the announcer keeps switching between these casual and polite forms throughout the game. Why does she make these changes in her speech? Check out the dialogue below, and see if you can apply the concepts you learned to account for her language choices. Once you've had a chance to think about the effects of だ and です in this dialogue, hover or tap the blurred text below to reveal our analysis and compare it with your own.

- バッターは4番中田です。いい打球ですが...ファウルです。2球目...いい打球だ!

- The next batter is number 4, Nakata. A good hit, but it's a foul. The second pitch... he knocks it out of the park!

In the next section on how です and だ are used in writing, you'll see how writers can also play with this system to add character and finesse to their writing.

Conceptualizing です and だ in Writing

Now that you have been initiated into the secrets of だ and です, let's turn our attention to how they are used in different types of writing. Along the way, you will see how the general concepts of だ and です we've seen in speaking can also be applied to writing, albeit with sometimes differing effects. You will also get a feel for the differences between written and spoken Japanese, as well as their ever-increasing similarities.

We'll begin with the conceptual difference between です and だ in Japanese writing. This section will also feel very abstract, so we'll rely on images for help. Take a look at the image below to get a visual sense of how です feels in writing.

Remember how です is used in speech for communication that is consciously directed toward other people? This same idea applies to written Japanese.

In the image, the writer is directly addressing the readers. Just like spoken です, the writer's focus is on the audience. They are thinking about the reader as they write, and the intention is to produce polite, socially-aware communication. Writing with です therefore carries a soft tone and gives the impression that the writer is speaking to the reader.

So what about だ? Remember, だ statements in spoken Japanese allow a speaker to focus on self-expression. In other words, these statements are not overtly interactional because they stay within the speaker's personal space.

In writing, the theory remains the same. Unlike です, だ is used in formal written communication to take on an informative and objective tone. In the image above, the writer is focused on what they want to express in their writing, and the readers are interested in the information being relayed.

In more casual writing, such as chat or social media posts between friends, だ works in just about the same way as it does in spoken Japanese.

In other words, the underlying principle of だ for self-expression holds, but has a differing effect according to the context.

Again, our concepts might feel a bit hazy at this point, but this is because they are applicable across all contexts. In order to make these concepts more concrete, in a moment we'll be taking a look at various different media, from formal to informal and everything in between.

Before diving into that, however, let's see how this conceptual understanding of だ and です can be applied to traditional Japanese writing styles.

Traditional Writing Styles and Rules

Japanese writing can be divided into two major styles, often called です・ます style and だ・である style.

The term です・ます style is simply another way to refer to the polite style with です that we have already looked at in the speaking section. This style follows the same broad concept that です represents in speaking. In other words, です shows engagement with social rules and therefore directs the writing specifically toward the reader.

The だ・である style can be equated with that of だ in speaking, though its impact varies dramatically according to the level of formality. This fits in with the idea that だ is "raw" and can therefore be used to show naked emotions and bare facts alike, without the sense of social etiquette that is part and parcel of です・ます style.

If we delve a little deeper, だ・である style can also be broken down further into two distinct styles. With impeccable logic, these two styles are known as だ style and—you guessed it—である style. They are often treated as one and the same because they come under the umbrella of だ for self-expression, implying a lack of focus on the audience.

When it comes to actual writing styles, however, だ style and である style are usually considered separate as they carry different nuances. To put it simply, だ is plain and である is a bit more authoritative and formal.

For that reason, だ style is usually referred to as plain style, and である style is referred to variously in textbooks as plain-formal, literary, or expository style. です・ます style remains one set, referred to as polite style.

The Rule of Consistency

This rule of consistency is particularly important when it comes to academic papers, school essays, newspaper reports, and other types of "informative" writing.

With all these different writing styles, it will come as no surprise that there are some set rules of thumb that writers are expected to follow. One such rule is to stick to the same style within one piece of writing. This rule of consistency is particularly important when it comes to academic papers, school essays, newspaper reports, and other types of "informative" writing. Going against this rule could make the writing seem of lower quality and is generally frowned upon.

In many genres of writing, however, the styles may be mixed. The rules tend to be bent, or outright broken, when it comes to blogs, novels, or any other more "expressive" form of writing. In such writing, this mixing is used as a clever device to convey complex nuances.

Mastering this concoction is the key to fully understanding Japanese writing. By the end of this section, we hope you will have a thorough understanding of how だ and です function in Japanese writing. To get you there, we're going to take a look at writing style across a range of different genres, starting with the ones that follow the rules. Just like Picasso, let's learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.

Genres with Consistent Style

As we just learned above, a basic rule of Japanese writing is to stick with one style. So if you start with です・ます style, don't switch to だ style or である style halfway through your composition. In this section, we will walk you through a variety of genres that tend to uphold this rule.

We're going to start with the formal end of written Japanese and gradually work our way through various media to finish with the most casual. This means that we will begin with である. While texts that use である style are the same in other ways to texts with だ, the simple fact of switching out だ with である can change the feeling the reader has when they read the text.

Academic Writing

である style is overwhelmingly employed in academic writing, particularly in published research papers, theses, and dissertations. This is because the information under discussion is objective, rigorous, and intended to be persuasive, making the authoritative and formal tone of である fitting in this kind of writing.

Lighter academic writing exercises such as high school essays, on the other hand, tend to use だ style instead. This is because である style is a bit too assertive and authoritative, and generally feels inappropriate for not-so-authoritative writing. In fact, one of our writers, Mami, was laughed at by her literature teacher back in high school for writing an essay in である style. The である style can have a high-and-mighty connotation, so its use as base form is generally limited.

So the choice of writing style is more about the text's content and intended audience. である style is often used when the text is issued by some sort of authority, whereas plain old だ style is for more neutral and lighter texts.

Laws, Regulations and Other Official Documents

As we've discussed above, である is primarily used in formal contexts, and conveys a certain authority in a stern, official sounding manner. The image above shows the first part of the Japanese Constitution. Needless to say, this is a very formal document, and である is the obvious choice to convey this formality.

The writing is not aimed at communicating with the reader but stating information that is "set in stone" and not up for discussion.

While です・ます style is obviously inappropriate, the formal だ style would not be too far off the mark. However, である style is favored in these contexts in order to convey the gravity of the subject matter.

Official documents, such as government reports and policy documents, are also primarily written in である style, like this document below.

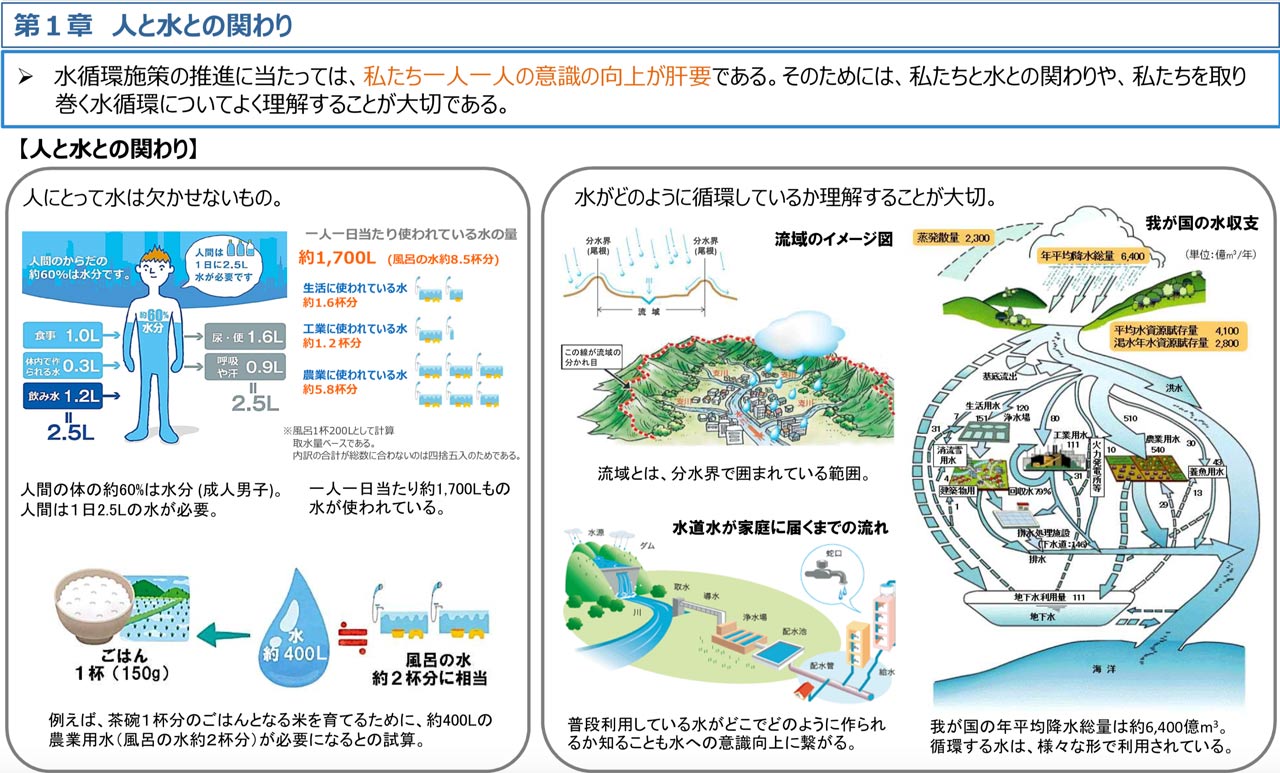

However, to make these kinds of documents more user-friendly and easier to read, they sometimes make use of other writing styles. The following image is a page from a government-issued information packet, and three different styles are mixed in here.

In the image, the main, "informative" part of the document is written in である style, conveying facts in an authoritative manner. However, です style appears inside the speech bubble. Just like in actual speech, です・ます style shows that the writer is trying to make their message more accessible to the readers by creating the feeling that they are talking to their audience.

です・ます style is often associated with simple, easy-to-read instructions or guidelines addressing the reader directly. So even in formal writing, if information is portrayed as being directed toward the reader, です・ます style will almost always be favored.

Finally, you'll notice in this text that there are quite a few sentences that end with neither です・ます style nor である style, but simply with a noun or na-adjective. We won't go into this in detail in this article, but suffice it to say that this sort of ending is generally reserved for situations when clever use of space is paramount, such as captions, bullet points, and newspaper headlines. It can also be used to add some variety to a text and make it feel less monotonous.

We should point out that, even though styles are mixed within the document, the style within each section remains consistent, so it is still following the rules.

News Media

The purpose of news media is to convey information in a purely objective manner without the sense that this information carries authority. Here, だ style is usually preferred over である style to reflect the ideal that journalists should maintain a neutral voice in their writing, rather than trying to persuade the reader of their point of view.

As we mentioned earlier, headlines and photo captions omit です, だ, or である to conserve space, and this can even be seen within the body of articles to add a bit of variety to the text. Some news magazines also mix だ and である styles to give more flavor to their writing.

Within the same newspaper, the style can also vary depending on the type of writing. In editorials and other pieces that are addressing the reader directly, です・ます style can be used. Other styles, including である or very casual styles, can also be mixed in strategically to spice up writing and convey various nuances and different personas.

Not all news media outlets follow these general principles, however. While most online newspapers use だ style for fact reporting, NHK News Web has opted for です・ます style.

There are two possible reasons for this choice. Unlike newspapers, NHK doesn't have a print edition, and so it doesn't have to work within a limited space. That means they can freely address readers directly and politely by using です・ます to make their articles more accessible and sound friendly.

Another explanation could be that NHK is first and foremost a broadcaster, which might have influenced their choice of a more "spoken" style. We sent out a question to NHK, asking why they chose です・ます style, but the answer hasn't come in yet. We'll update this article with the reason once we hear from them. NHKさん、おねがいしま〜す!

Genres with Mixed Writing Style

Good stories are full of fascinating writing techniques, and in Japanese, the mixture of writing styles is one such technique.

So far we've examined genres of writing that are stylistically consistent, but there are plenty of situations where writers can depart from convention and rules can be bent or broken. When's the last time a novel moved you to tears? Or made you feel excited, sad, or scared? Novelists have a whole host of tricks up their sleeves to make their writing jump off the page and under our skin.

Good stories are full of fascinating writing techniques, and in Japanese, the mixture of writing styles is one such technique. This intentional breaking of the style consistency rule has become increasingly commonplace in contemporary Japanese writing, from novels and essays to everyday casual messages or social media posts.

This article isn't a course on Japanese literary techniques, so we'll only provide a glimpse here. Still, you'll come away with a good grip of how to manipulate readers by the strings of です and だ, according to the underlying concepts of each.

Creative Writing

Creative writers tend to select one style as the prominent voice in their writing. However, they can intentionally mix in other styles to add different effects. Let's look at two ways in which these writing techniques are applied.

The following is an excerpt from Banana Yoshimoto's critically acclaimed novel, Kitchen.

しんと暗く、なにも息づいていない。見慣れていたはずのすべてのものが、まるでそっぽをむいているではないですか。私はただいまと言うよりはお邪魔しますと告げて抜き足で入りたくなる。

Cold and dark, not a sigh to be heard. Everything there, which should have been so familiar, seemed to be turning away from me. I entered gingerly, on tiptoe, feeling as though I should ask permission. (Translation by Megan Backus.)

Yoshimoto mainly uses だ style in this novel, but she switches to です style in the second sentence to make the reader feel as though the character is stepping out of the story momentarily to directly address the reader. This adds a feeling of sudden interaction with the reader, which is nearly impossible to reflect in the English translation.

Now let's take a look at another way of mixing styles in this excerpt from Osamu Dazai's short story, Villon's Wife.

その夜、十時すぎ、私は中野の店をおいとまして、坊やを背負い、小金井の私たちの家にかえりました。やはり夫は帰って来ていませんでしたが、しかし私は、平気でした。あすまた、あのお店へ行けば、夫に逢えるかも知れない。どうして私はいままで、こんないい事に気づかなかったのかしら。きのうまでの私の苦労も、所詮は私が馬鹿で、こんな名案に思いつかなかったからなのだ。私だって昔は浅草の父の屋台で、客あしらいは決して下手ではなかったのだから、これからあの中野のお店できっと巧く立ちまわれるに違いない。現に今夜だって私は、チップを五百円ちかくもらったのだもの。

Sometime after ten, I strap the boy to my back and return to our home in Koganei. My husband isn't here, but I'm not bothered. Tomorrow I'll be back at the shop, and maybe I'll see him there. I wonder why I didn't think of this in the first place. I did all that agonizing only because I was too stupid to come up with this brilliant little plan. I was always good at dealing with customers when I was helping at my father's oden stand, and I know I'll get on well at the place in Nakano. Tonight, in fact, I earned almost five hundred yen in tips. (Translation by Ralph McCarthy.)

In this story, the main character uses です・ます style for general narration, but switches to だ style when she begins to share her inner thoughts. This gives the sense that the character is turning her awareness inward but is allowing the reader in on her internal monologue.

While our examples are limited to novels, authors use these style-mixing techniques in a range of creative writing genres, from essays and editorials to advertisements and newspaper columns. Even in expository writing such as textbooks, guide books, or blog posts, you may notice that style mixing is used to make the writing more impactful and engaging.

Social Media Posts

In fact, most native Japanese speakers use style mixture to some extent, and social media posts are a great example of this.

While official accounts—like those belonging to government authorities or the local police force—post formal messages that are consistent in style, casual posts tend to mix styles depending on what the writer wants to convey. This kind of writing is often close in style to spoken Japanese, and similar rules apply.

Let's have a look at a typical social media post to give you an idea:

Original:

昨日撮ったツツジの写真です

満開の花はやっぱりきれいだー

Translation:

Here's a picture of a rhododendron that I took yesterday. Flowers in full bloom really are beautiful!

The first sentence introduces the topic and tells the account's followers what is in the attached picture. Then, in the second sentence, the style switches to casual to express the writer's inner thoughts, admiring the beauty of the flowers in full bloom.

Social media posts are often loaded with style mixing, as people can freely weave their thoughts in a message to their followers.

Text Messages

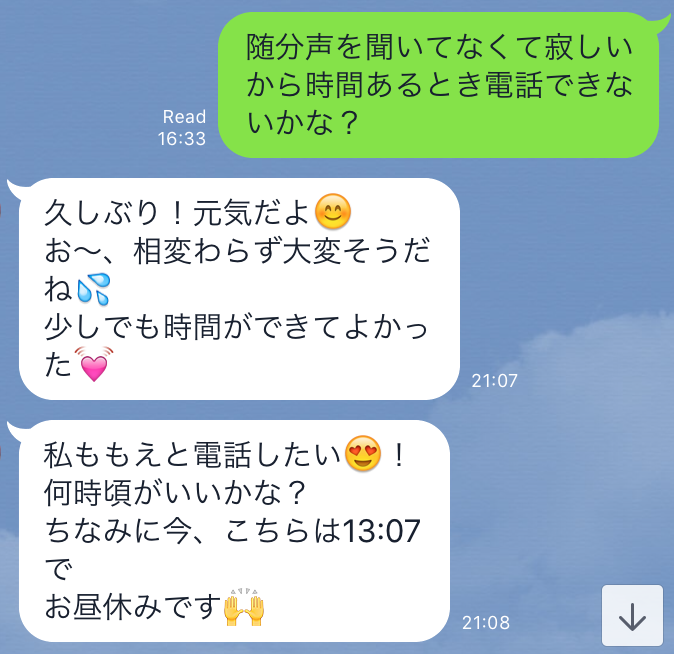

Text messages are another good example of how people mix different writing styles in a similar way to when they are speaking.

The biggest difference from Twitter is that you are interacting with a specific person or a group of people when texting. This means that your writing style is affected by the relationship between you and the recipients of your texts.

Look at the text message on the LINE screen to the left. There are two people in this LINE chat, one lives in the US and the other in Japan. They are trying to set up a time for a phone call. You can see that they mostly use a casual writing style, which is a good sign that they are close friends. However, in the final message you can see that the writer switches to です when referring to her lunch break at work:

ちなみに今、こちらは13:07でお昼休みです。

By the way, it's 1:07 p.m. here (in Japan), and I'm on my lunch break.

So why does she suddenly use です here, even though she's texting with a close friend? If you recall what we talked about in the speaking section of this article, the use of です is all about distance. While this can result in heightened formality and politeness, it can also allow us to create distance between our personal self and the social roles that we play. In the case of this LINE text, the person is using です to place distance between herself as a friend and herself as an office worker. This strategy also adds variety to the writing while drawing attention to certain information.

In fact, writing style mixture happens almost as much in texting as it does in speech. In our technological age, texting is quickly becoming more common and more interactional, and is beginning to blur the lines between written and spoken language. You will see style mixing in text messages that has the same effects as in speech, but don't be alarmed. With your newly-found conceptual understanding of です and だ, have confidence that you'll be able to interpret its meaning.

だ Takeaway

Who would have thought that there is so much to learn about です and だ? While this article was long and winding, we hope you can see how the basic concepts of です as socially-oriented and だ as self-oriented have remained consistent throughout. The effect that these concepts have on communication can vary depending on context, but underneath it all, their basic meaning remains the same.

Now that you're familiar with these core concepts, try applying them as you come across です and だ in real life. What shade of meaning do they add to a sentence? Better yet, experiment with applying these concepts to your own Japanese. Rather than trying to memorize rules from your textbook, think of these concepts as a kind of toolkit you can use to express yourself in a way that is most appropriate to your personality, and to all the weird and wonderful situations you find yourself in.

これでおしまいです。