Basic counting in Japanese is pretty easy, but the topic can get much, much more complex.

If you're a new student of Japanese, one of the first things you'll learn is how to count. Basic counting in Japanese is pretty easy, but the topic can get much, much more complex. And while plenty of people can count to ten in Japanese (remember those introductory martial arts classes at your local dojo?), there is much more to learn. Besides counting from 1 to 100, in this lesson you'll learn about large number units: billions, trillions, even vigintillions and duovigintillions! You'll peek behind the curtain of an East Asian Buddhist sutra, which includes 123 units of counting. And you'll be introduced to the Wago style of counting—that is, how to count in archaic Japanese. That being said, there are some situations where it's still commonly used today.

Prerequisites: To get the most out of this article, you'll need to be able to read Hiragana. If you can't do this yet, check out our Hiragana guide, which uses mnemonics to teach you how to learn to read them all in a day. You'll also need to know a little kanji, though you can always look up the ones you don't know in your favorite Japanese dictionary.

Regardless of your skill level, you're definitely going to learn something about counting in Japanese, and some of your newfound knowledge just might eclipse that of a native Japanese speaker. (Really!) Okay, 1…2…3… let's get started!

- The Two Methods of Counting in Japanese: Kango & Wago

- Counting in Kango, the Chinese Style

- Counting in the 100s, 1,000s, and Beyond

- More Unit Names in Japanese Counting

- Decimal Places in Japanese Counting

- Complex Kanji For Fraud Prevention—Daiji

- Counting in Wago, the Japanese Style

- Wago and Counting to 10 and Above

- Wago and Counting to 100 and Beyond

- Gairaigo Counting

- It's Time to Count Down…

- Counting in Japanese Study Spreadsheet

Before you get started, consider listening to the podcast of this episode! It's a good overview, and goes deeper into several of these topics. To get all of Tofugu's podcast episodes, be sure to subscribe to the podcast.

The Two Methods of Counting in Japanese: Kango & Wago

To compress a long history into a much, much shorter one, modern Japanese comes from three different sources. Many words are from the original Japanese language, which is called Wago 和語 or Yamato-kotoba 大和言葉. Other words originate from Chinese, called Kango 漢語, and the rest, called Gairaigo 外来語, are foreign words (that are not Kango) that have slipped into the language over time. To oversimplify, modern Japanese is a mix of all three.

Because of that history, there are two primary ways to count in Japanese now. As you might be able to guess, one comes from the Wago system while the other comes from Kango and the Chinese counting system. Let's compare them, 1 through 10.

| Wago | Kango | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ひとつ / ひ | いち |

| 2 | ふたつ / ふ | に |

| 3 | みっつ / み | さん |

| 4 | よっつ / よ | し |

| 5 | いつつ / い(つ) | ご |

| 6 | むっつ / む | ろく |

| 7 | ななつ / な | しち |

| 8 | やっつ / や | はち |

| 9 | ここのつ / こ | く or きゅう |

| 10 | とお | じゅう |

They look and sound completely different, don't they? But don't worry. You won't be required to remember two complete sets of counting systems. In modern Japanese, the Wago version is usually only used through the first ten numbers. Kango is used from 1 to… forever, theoretically.

Counting in Kango, the Chinese Style

Now, here's a slightly different chart, one with kanji and Kango numbers. Can you spot the difference between it and the first chart's Kango column?

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 零 | れい or ゼロ | |

| 1 | 一 | いち | |

| 2 | 二 | に | |

| 3 | 三 | さん | |

| 4 | 四 | し or よん | |

| 5 | 五 | ご | |

| 6 | 六 | ろく | |

| 7 | 七 | しち or なな | |

| 8 | 八 | はち | |

| 9 | 九 | く or きゅう | |

| 10 | 十 | じゅう |

Because of that history, there are two primary ways to count in Japanese now. As you might be able to guess, one comes from the Wago system while the other comes from Kango.

One difference between the two charts is that the second contains the number 0. The Kango word for 0 is れい; it can also be written as ゼロ. The English word for 0 was imported in the Meiji period (1868–1912), and is more commonly used nowadays.

But there's another difference in the second chart. Note the extra Kango reading for 四/4, 九/9, and 七/7. The Kango word for 4 is し, which sounds just like 死—"death." Hmmm. Similarly, 九 can be read as きゅう. The original reading, く, sounds the same as 苦, which means "suffering." Both 4 and 9 received alternative versions because people wanted to avoid these negative associations. The secondary reading for 7 (なな) is used because しち sounds too much like いち or even し. Think of it as similar to the potential confusion in English between the pronunciation of the numbers "50" and "15."

Here's another twist: the alternate readings for 4 and 7 come from the Wago readings of the numbers. Including ゼロ (zero), our Kango counting list is actually a mix of English, Old Japanese, and Chinese! As for how common it is to learn to count with the alternative versions of 4 and 7, pre– and primary schoolteachers are teaching よん and なな to kids nowadays to prevent confusion in counting. It's likely to become the standard, if it isn't already. Either way, both versions are common, and whichever one you choose, most folks will understand you just fine.

10 and Above

For numbers larger than 10, it's actually very simple to count in Japanese. You don't have to memorize any new words like "eleven," "twelve," "twenty," "thirty," and so on; you simply use a combination of the numbers you've already memorized.

For example, if you want to say "11" in Japanese, you just break it out into the parts 10 and 1. 10 in Japanese is じゅう and 1 is いち. Combine the two (じゅう+いち) and you get じゅういち. Congrats!

What about 23? Same thing: break it out into the parts 20 and 3. Start by breaking 20 down into 2 and 10: 2 in Japanese is に; 10 is じゅう. Combine them to get にじゅう, which is 20. 3 is さん, so if you combine 20 and 3 you get にじゅうさん. Easy, right?

Although this may seem a little complicated at first, it becomes pretty easy if you do it a few times. You don't even need to do any actual math. It's more like a simple number puzzle. Assuming you've memorized 1 through 10 already, you can use the following charts to guess what the numbers will be, then check your answers. By the time you're done, you'll be able to count to 100 in Japanese!

10 to 19

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 十 | じゅう |

| 11 | 十一 | じゅういち |

| 12 | 十二 | じゅうに |

| 13 | 十三 | じゅうさん |

| 14 | 十四 | じゅうし or じゅうよん |

| 15 | 十五 | じゅうご |

| 16 | 十六 | じゅうろく |

| 17 | 十七 | じゅうしち or じゅうなな |

| 18 | 十八 | じゅうはち |

| 19 | 十九 | じゅうく or じゅうきゅう |

20 to 29

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 二十 | にじゅう |

| 21 | 二十一 | にじゅういち |

| 22 | 二十二 | にじゅうに |

| 23 | 二十三 | にじゅうさん |

| 24 | 二十四 | にじゅうし or にじゅうよん |

| 25 | 二十五 | にじゅうご |

| 26 | 二十六 | にじゅうろく |

| 27 | 二十七 | にじゅうしち or にじゅうなな |

| 28 | 二十八 | にじゅうはち |

| 29 | 二十九 | にじゅうく or にじゅうきゅう |

30 to 39

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango |

|---|---|---|

| 30 | 三十 | さんじゅう |

| 31 | 三十一 | さんじゅういち |

| 32 | 三十二 | さんじゅうに |

| 33 | 三十三 | さんじゅうさん |

| 34 | 三十四 | さんじゅうし or さんじゅうよん |

| 35 | 三十五 | さんじゅうご |

| 36 | 三十六 | さんじゅうろく |

| 37 | 三十七 | さんじゅうしち or さんじゅうなな |

| 38 | 三十八 | さんじゅうはち |

| 39 | 三十九 | さんじゅうく or さんじゅうきゅう |

40 to 49

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango |

|---|---|---|

| 40 | 四十 | よんじゅう |

| 41 | 四十一 | よんじゅういち |

| 42 | 四十二 | よんじゅうに |

| 43 | 四十三 | よんじゅうさん |

| 44 | 四十四 | よんじゅうし or よんじゅうよん |

| 45 | 四十五 | よんじゅうご |

| 46 | 四十六 | よんじゅうろく |

| 47 | 四十七 | よんじゅうしち or よんじゅうなな |

| 48 | 四十八 | よんじゅうはち |

| 49 | 四十九 | よんじゅうく or よんじゅうきゅう |

Note: Numbers 40–49 are almost always read as よんじゅう and not しじゅう. Occasionally you'll hear an elderly person use しじゅう when talking about their age. You'll also occasionally hear idioms and phrases from older times that use the しじゅう reading. For example, 四十肩 (しじゅうかた) means "frozen shoulder." 四十九日 (しじゅうくにち) refers to the 49th day after one's death—a special day in Japanese Buddhism. And 四十七士 (しじゅうしちし) refers to the 47 loyal retainers of the Akō Domain. There's more, but you get the idea. Using しじゅう is considered archaic, but you may still run across it from time to time.

50 to 59

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 五十 | ごじゅう |

| 51 | 五十一 | ごじゅういち |

| 52 | 五十二 | ごじゅうに |

| 53 | 五十三 | ごじゅうさん |

| 54 | 五十四 | ごじゅうし or ごじゅうよん |

| 55 | 五十五 | ごじゅうご |

| 56 | 五十六 | ごじゅうろく |

| 57 | 五十七 | ごじゅうしち or ごじゅうなな |

| 58 | 五十八 | ごじゅうはち |

| 59 | 五十九 | ごじゅうく or ごじゅうきゅう |

60 to 69

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango |

|---|---|---|

| 60 | 六十 | ろくじゅう |

| 61 | 六十一 | ろくじゅういち |

| 62 | 六十二 | ろくじゅうに |

| 63 | 六十三 | ろくじゅうさん |

| 64 | 六十四 | ろくじゅうし or ろくじゅうよん |

| 65 | 六十五 | ろくじゅうご |

| 66 | 六十六 | ろくじゅうろく |

| 67 | 六十七 | ろくじゅうしち or ろくじゅうなな |

| 68 | 六十八 | ろくじゅうはち |

| 69 | 六十九 | ろくじゅうく or ろくじゅうきゅう |

70 to 79

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango |

|---|---|---|

| 70 | 七十 | ななじゅう |

| 71 | 七十一 | ななじゅういち |

| 72 | 七十二 | ななじゅうに |

| 73 | 七十三 | ななじゅうさん |

| 74 | 七十四 | ななじゅうし or ななじゅうよん |

| 75 | 七十五 | ななじゅうご |

| 76 | 七十六 | ななじゅうろく |

| 77 | 七十七 | ななじゅうしち or ななじゅうなな |

| 78 | 七十八 | ななじゅうはち |

| 79 | 七十九 | ななじゅうく or ななじゅうきゅう |

Note: The 七十s are almost always read ななじゅう. You may hear older people use しちじゅう, but it's not very common.

80 to 89

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | 八十 | はちじゅう |

| 81 | 八十一 | はちじゅういち |

| 82 | 八十二 | はちじゅうに |

| 83 | 八十三 | はちじゅうさん |

| 84 | 八十四 | はちじゅうし or はちじゅうよん |

| 85 | 八十五 | はちじゅうご |

| 86 | 八十六 | はちじゅうろく |

| 87 | 八十七 | はちじゅうしち or はちじゅうなな |

| 88 | 八十八 | はちじゅうはち |

| 89 | 八十九 | はちじゅうく or はちじゅうきゅう |

90 to 99

| Arabic | Kanji | Kango |

|---|---|---|

| 90 | 九十 | きゅうじゅう |

| 91 | 九十一 | きゅうじゅういち |

| 92 | 九十二 | きゅうじゅうに |

| 93 | 九十三 | きゅうじゅうさん |

| 94 | 九十四 | きゅうじゅうし or きゅうじゅうよん |

| 95 | 九十五 | きゅうじゅうご |

| 96 | 九十六 | きゅうじゅうろく |

| 97 | 九十七 | きゅうじゅうしち or きゅうじゅうなな |

| 98 | 九十八 | きゅうじゅうはち |

| 99 | 九十九 | きゅうじゅうく or きゅうじゅうきゅう |

Note #1: The 九十s are almost always read as きゅうじゅう. The main exception to this is with certain location names, such as 九十九里浜 (くじゅうくりはま).

Note #2: くじゅう is a homophone of 苦汁, which means "bitter soup" and figuratively means "hard time" or "bitter experience." 苦渋, another homophone of くじゅう, means "deeply troubled" or "distressed." You can understand why most people would want to say きゅうじゅう instead of くじゅう.

And with that, you can count to 99 in Japanese! If you study the patterns closely, you'll discover some that are repeated over and over again. Once you figure out those, you'll be able to easily count in Japanese and, with practice, use Japanese numbers easily and without a hitch.

Counting in the 100s, 1,000s, and Beyond

Counting above 99 in Japanese is just as simple. The only difference is the numbers are going to get longer. You will also need to learn a few new unit names.

From 1 to 10,000, the unit names change with each decimal. After 10,000, though, new units change names every 104. It's confusing, because in English you get new unit names every three decimal points (after 1,000). Let's compare, first in English:

1,000: thousand

1,000,000: million

1,000,000,000: billion

1,000,000,000,000: trillion

Now in Japanese:

1,0000: 一万 (いちまん)

1,0000,0000: 一億 (いちおく)

1,0000,0000,0000: 一兆 (いっちょう)

1,0000,0000,0000,0000: 一京 (いっきょう)

If you can wrap your mind around that… good on you! It can be confusing to go from English to Japanese unit names and vice-versa. (I remember once trying to withdraw a small amount of money from a bank in Canada and accidentally asking for an absurdly large sum; it made everyone laugh because I wasn't used to the English counting system. I'm still not perfect at it, but with practice it's gotten better. Keep trying!)

It can be confusing to go from English to Japanese unit names and vice-versa.

Speaking of which, how do you suppose you would count between 一万 (いちまん /10,000) and 一億 (いちおく/100,000,000)? It's similar to how you did it earlier, only with larger numbers. Just as in English you would say "ten thousand," the Japanese read 100,000 as 十万 (じゅうまん)—"ten ten-thousands." Add another zero and you would say 百万 (ひゃくまん): one hundred ten-thousands, a.k.a 1,000,000—"one million"—in English.

Some general counting rules for big numbers are worth remembering. 四百, 四千, and 四万 are always read with よん for 4; 七百, 七千, and 七万 are always read with なな for 7; 九百, 九千, and 九万 are always read with きゅう for 9. This pattern continues into higher units of counting as well. Finally, when a 0 appears in the number, you don't have to read it out loud (with a couple of exceptions we'll tell you about later). So "303" would be さんびゃくさん, not さんびゃくれいさん or さんびゃくゼロさん.

Readings for numbers can be changed when 百, 千, 兆 or 京 come after them. For these rules, please see the following chart:

| Numeral | 百 (ひゃく) | 千 (せん) | 兆 (ちょう) | 京 (きょう) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (いち) | いっちょう | いっきょう | ||

| 3 (さん) | さんびゃく | さんぜん | ||

| 6 (ろく) | ろっぴゃく | ろっきょう | ||

| 8 (はち) | はっぴゃく | はっせん | はっちょう | はっきょう はちきょう |

| 10 (じゅう) | じゅっちょう | じゅっきょう | ||

| 何 (なん) | なんびゃく | なんぜん |

Let's practice reading numbers for a little bit. Afterward, we'll get into the really obscure stuff. Ready?

Practice

- 123/百二十三

- ひゃくにじゅうさん

- 567/五百六十七

- ごひゃくろくじゅうなな

Note: In this example, なな could have been しち, but なな is more common.

- 707/七百七

- ななひゃくなな

Note: 七百 is always ななひゃく, never しちひゃく. The last なな could have been しち, but なな is more common. Remember that you don't need to read the zero.

- 1,000/千

- せん

Note: 1,000 can be read as 一千 (いっせん) as well, but just 千 on its own is more common.

- 1964/千九百六十四

- せんきゅうひゃくろくじゅうよん

Note: 九百 is always きゅうひゃく, never くひゃく. よん can be し, but よん is more common.

- 2,481/二千四百八十一

- にせんよんひゃくはちじゅういち

Note: 四百 is always よんひゃく, never しひゃく.

- 10,000/一万

- いちまん

Note: 10,000 always has to be いちまん ("one ten-thousand"). It can't just be まん.

- 10,059/一万五十九

- いちまんごじゅうきゅう

Note: The last きゅう can be く, although きゅう is more common.

- 330,479/三十三万四百七十九

- さんじゅうさんまんよんひゃくななじゅうきゅう

Note: 四百 is always read よんひゃく, not しひゃく. 七十 could be read as しちじゅう by older people, but usually it's ななじゅう. The last 九 could be く, but きゅう is more common.

- 199,999,099/一億九千九百九十九万九千九十九

- いちおくきゅうせんきゅうひゃくきゅうじゅうきゅうまんきゅうせんきゅうじゅうきゅう

Note: 1,0000,0000 has to be read as 一億 (いちおく), and not just 億 on its own. 九千 is always きゅうせん and never くせん. 九百 is always きゅうひゃく and never くひゃく. 九十 is always きゅうじゅう, except for special cases such as the name of a location. Finally, 九万 is always read きゅうまん, not くまん.

I hope that practice helped you to see some of the patterns in Japanese counting. Experience really is the best teacher, though, so keep reading out numbers and it will become natural soon.

More Unit Names in Japanese Counting

For those of you who might be numbers otaku, cosmologists, or the latest Mega Millions winners, the following chart contains really big numbers. It gets kind of funny, too, as if the people who came up with these names were in on some kind of joke. For example, the second-to-last unit name for 1064—a.k.a. 10 vigintillion—is 不可思議 (ふかしぎ), which means "incomprehensible" or "mystery." Then there's the last unit name on the list: 1068, a.k.a. 100 duovigintillions. In Japanese, it's called 無量大数 (むりょうたいすう), which means "immeasurable large number." No kidding!

| 一 (いち) 100 |

十 (じゅう) 101 |

百 (ひゃく) 102 |

千 (せん) 103 |

| 万 (まん) 104 |

十万 105 |

百万 106 |

千万 107 |

| 億 (おく) 108 |

十億 109 |

百億 1010 |

千億 1011 |

| 兆 (ちょう) 1012 |

十兆 1013 |

百兆 1014 |

千兆 1015 |

| 京 (けい、きょう) 1016 |

十京 1017 |

百京 1018 |

千京 1019 |

| 垓 (がい) 1020 |

十垓 1021 |

百垓 1022 |

千垓 1023 |

| 𥝱 (じょ)、秭 (し) 1024 |

十𥝱 1025 |

百𥝱 1026 |

千𥝱 1027 |

| 穣 (じょう) 1028 |

十穣 1029 |

百穣 1030 |

千穣 1031 |

| 溝 (こう) 1032 |

十溝 1033 |

百溝 1034 |

千溝 1035 |

| 澗 (かん) 1036 |

十澗 1037 |

百澗 1038 |

千澗 1039 |

| 正 (せい) 1040 |

十正 1041 |

百正 1042 |

千正 1043 |

| 載 (さい) 1044 |

十載 1045 |

百載 1046 |

千載 1047 |

| 極 (ごく) 1048 |

十極 1049 |

百極 1050 |

千極 1051 |

| 恒河沙 (ごうがしゃ) 1052 |

十恒河沙 1053 |

百恒河沙 1054 |

千恒河沙 1055 |

| 阿僧祇 (あそうぎ) 1056 |

十阿僧祇 1057 |

百阿僧祇 1058 |

千阿僧祇 1059 |

| 那由他 (なゆた) 1060 |

十那由他 1061 |

百那由他 1062 |

千那由他 1063 |

| 不可思議 (ふかしぎ) 1064 |

十不可思議 1065 |

百不可思議 1066 |

千不可思議 1067 |

| 無量大数 (むりょうたいすう) 1068 |

If this looks like a lot, apparently in the Avatamsaka Sutra (法華経/ほっけきょう), the "Flower Garland Sutra" of East Asian Buddhism, the reader is introduced to 123 different independent number units. And there's a number unit that's even higher than our "immeasurable large number": 不可説不可説転—the number 10372183838819776444413065976876496481295! What the heck?!

Decimal Places in Japanese Counting

- 点(てん)

- decimal point

In English, the decimal point is just called "point" when it's read aloud. ("Pi equals three point one four one five…") In Japanese, the word "decimal point" 小数点 (しょうすうてん) is likewise shortened to just 点 (てん). 点 means "dot." Here's another tip: normally, when reading numbers in Japanese, you pause every four digits. When there is a 点 in the number, it's treated as one of the four. In Japanese, pi would be read like this:

- 3.141592653589793238…

- さん てん いちよん、 いちごきゅうに、 ろくごさんご、 はちきゅうななきゅう、 さんにさんはち…

Remember that you don't read 0s out loud? Well, here are those couple of exceptions we promised.

- When you're reading individual numbers aloud (like when you're providing someone with your credit card number).

- When a number with a decimal point starts with a zero.

For example:

- 0.15

- れいてんいちご

That first zero must be read as れい. But all the zeros after, or any zeros being read that don't start a decimal number, can be read as either れい or ゼロ. Here's another example:

- 0.150378

- れいてんいちご れいさんななはち

- 0.150378

- れいてんいちご ゼロさんななはち

In most cases, 4s, 7s, and 9s should be read as よん, なな, and きゅう. The only exception is if you're reading them aloud, 1 through 10, in order.

Although it's less common than the way we've described above, we want to alert you to a few unexpected usages of decimals in Japanese.

| Names | Reading | Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| 一 | いち | 100 |

| 分 | ぶ | 10-1 |

| 厘 or (釐1) | りん | 10-2 |

| 毛 or (毫1) | もう | 10-3 |

| 糸 or (絲1) | し | 10-4 |

| 忽 | こつ | 10-5 |

| 微 | び | 10-6 |

| 繊 | せん | 10-7 |

| 沙 | しゃ | 10-8 |

| 塵 | じん | 10-9 |

| 埃 | あい | 10-10 |

| 渺 | びょう | 10-11 |

| 漠 | ばく | 10-12 |

| 模糊 | もこ | 10-13 |

| 逡巡 | しゅんじゅん | 10-14 |

| 須臾 | しゅゆ | 10-15 |

| 瞬息 | しゅんそく | 10-16 |

| 弾指 | だんし | 10-17 |

| 刹那 | せつな | 10-18 |

| 六徳 | りっとく | 10-19 |

| 虚空 | こくう | 10-20 |

| 清浄 | しょうじょう | 10-21 |

| 阿頼耶 | あらや | 10-22 |

| 阿摩羅 | あまら | 10-23 |

| 涅槃寂静 | ねはんじゃくじょう | 10-24 |

Luckily for you, only 分 and 厘 got much use back in the day, and today they see even less usage—just in extremely specific situations. Here they are.

Body Temperature

分 can be used as part of one's body temperature measurement.

三十六度九分 (さんじゅうろくどくぶ), for example, is 36.9 ℃.

The 三十六 is "36," 度 is "degrees," and 九 is "9." It isn't until the end that we run into the 分. Checking the chart, we see this is 10-1, which means we move the decimal to the left one spot. 三十六度九分 is 36.9.

Batting Averages and Ratios

Both 分 and 厘 are used for ratios. One good example is a batting average in baseball.

- 彼は3割6分5厘で首位打者のタイトルを獲得した。

- He won the title with a .365 (batting) average.

Notice anything weird? 分 is for one decimal place (1/10), and 厘 is for two decimal places (1/100). But in the case of the example sentence above, the decimal slid one more spot, didn't it?

Let's figure out why. To start with, there is actually another unit name for "percentage," which is 割 (わり).

What 割 does is it multiplies the number before it by 10%. For example, 8割 is 80% (8 multiplied by 10%/割 = 80%). If you see 5割引き in a store, it means something is 50% off.

In the case of the batting average, though, 分 is considered to be 1/10th of 割, and 厘 is considered to be 1/100th 割. Confusing, isn't it? But don't fret. If you memorize these irregular use cases, you'll be good to go. That, or just don't go to baseball games.

Time

The 分 from the decimals chart gets used for time, too. Have you ever wondered why minutes are __分 in Japanese? Now you know. In this case, however, 分 represents not 1/10th, but 1/60th of an hour! It is matching time's sexagesimal system. We wrote all about this 1/60th use of 分 in our counters series.

Other Decimal Words

Obviously, there are many more decimal words—not a vigintillion, but a lot of them—with multiple uses and variations depending on who's using them. But it's interesting to see things like 毛 (hair), 糸 (string), 微 (minuteness), 塵 (dust), 埃 (dust), 模糊 (dim), 逡巡 (hesitation), 瞬足 (instantaneous), 刹那 (instant/moment), 虚空 (the sky/the air/empty space), and finally 涅槃寂静 (enlightenment leads to serenity).

Hopefully, though, you won't be talking about a number to the power of 10-16 very often. I'd recommend spending most of your decimal-related vocabulary study time on only the first few.

Idiomatic Usage of Kango Counting

Although the above units are barely used anymore, I was able to find and come up with some idiomatic usages that still remain.

See, even "useless" words can end up being useful in some way.

Complex Kanji For Fraud Prevention—Daiji

- 大字(だいじ)

- Complex versions of number kanji used to prevent fraud

With financial and legal documents, complex versions of the number kanji—known as 大字 (だいじ)—are used to help prevent fraud.

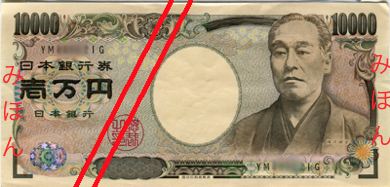

For example, take a look at this image of a Japanese ¥10,000 bill. Normally, the printed information would read 一万円 (いちまんえん). Here, however, it reads as 壱万円 (also いちまんえん), the kanji for "1" replaced with 壱, a more complicated version of 一.

Another example is the ¥2,000 bill. Normally it would read 二千円 (にせんえん). But here it appears as 弐千円. 弐 is the daiji version of 二. Why do these exist?

You've probably already figured it out. The number "一" can easily be turned into all manner of things: 二 (2), 三 (3), 五 (5), 六 (6), or 十 (10). What started out as ¥10,000 could be altered to ¥100,000 (一万円 → 十万円) or even ¥200,000 (if you used 廿万円). You can see the problem. And so, in 703, the Taihō Code was born, which required people to use the daiji system for official documents. The custom still exists today.

| Numbers | Kanji | Japanese Daiji (New) | Japanese Daiji (Old) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 〇 | 零 | 零 |

| 1 | 一 | 壱 | 壹、弌 |

| 2 | 二 | 弐 | 貳、貮 |

| 3 | 三 | 参 | 參、弎 |

| 4 | 四 | 肆 | 肆 |

| 5 | 五 | 伍 | 伍 |

| 6 | 六 | 陸 | 陆 |

| 7 | 七 | 漆、質 | 柒 |

| 8 | 八 | 捌 | 捌 |

| 9 | 九 | 玖 | 玖 |

| 10 | 十 | 拾 | 拾 |

| 20 | 廿、卄 | 弐拾 | 貳拾 |

| 30 | 卅、丗 | 参拾 | |

| 40 | 卌 | ||

| 100 | 百 | 陌、佰 | 佰 |

| 1,000 | 千 | 阡、仟 | 仟 |

| 1,0000 | 万 | 萬 | 萬 |

One quick note: when writing daiji, you basically write it like you write regular kanji numerals. There is one exception, though: sometimes you write in a "1" (壱) that you wouldn't usually write. For example, 110 can be either 百拾 (literally 100-10, the regular way to write numbers in Japanese) or 壱百壱拾 (1-100-1-10). But, you wouldn't write it in the Arabic style, like 壱壱零 (1-1-0).

Counting in Wago, the Japanese Style

If you remember back to the beginning of this lesson, we mentioned the Wago and Kango counting systems. We told you that you only need to remember 1 through 10 in Wago; that anything beyond that is archaic.

Wago Style Counting: 0 to 10

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | n/a | なし | n/a | なし |

| 1 | 一 | ひ or ひと | 一つ | ひとつ |

| 2 | 二 | ふ or ふた | 二つ | ふたつ |

| 3 | 三 | み | 三つ | みっつ |

| 4 | 四 | よ | 四つ | よっつ |

| 5 | 五 | い or いつ | 五つ | いつつ |

| 6 | 六 | む | 六つ | むっつ |

| 7 | 七 | な or なな | 七つ | ななつ |

| 8 | 八 | や | 八つ | やっつ |

| 9 | 九 | こ or ここの | 九つ | ここのつ |

| 10 | 十 | と or とお | 十 | とお or (そ)2 |

You'll definitely want to memorize ひとつ, ふたつ, みっつ, よっつ, いつつ, むっつ, ななつ, やっつ, ここのつ, and とお. Plenty of folks use the ひ, ふ, み, よ, etc., counting method, but it's not nearly not as common as the 〜つ version.

The つ is actually a suffix to count general things, similar to the modern counter 個 (こ). We'll have to save our discussion of the Japanese counters system for a different article—things get complicated—but be aware that the つ suffix can be really useful when you don't know the counter for something. That being said, it can only be used on numbers 1 to 9; for some reason, 10 doesn't get included. Above that, people used to use ち or ぢ, which we're going to see in a moment.

Trivia: The Wago counting system sounds very similar to the Ainu language counting system! 🤔

Wago and Counting to 10 and Above

Although you'll (probably) only rarely come across anyone counting past 10 using the Wago method, you will come across idiomatic examples of it now and then. There aren't many, so we'd suggest memorizing them as vocabulary. And unless you're studying Classical Japanese, memorizing the Wago counting method on its own may not be helpful.

And yet: if you're a regular Tofugu reader, you're probably curious about this kind of thing, and we think it's super interesting, too. Plus, you'll know something most normal Japanese folks don't!

Here's how you count in the Wago system:

Wago is pretty similar to Kango in that it combines numbers to make bigger ones. For Kango, 10 (じゅう) and 1 (いち) would make 11 (じゅういち). In Wago, the only difference is that you insert a word—あまり—between the 10 (とお) and the 1 (ひとつ). Thus 11 would be read とお あまり ひとつ.

あまり, you might know already, means "remainder," "the rest," or "leftovers." It's still used in mathematics when there's a remainder. For example, 11 divided by 10 equals 1 with a remainder of 1. In modern Japanese, the answer would be read as いち あまり いち.

Wago is pretty similar to Kango… In Wago, the only difference is that you insert a word—あまり—between the 10 (とお) and the 1 (ひとつ).

If you think about it, both the combining and the remaindering are basically the same thing. So what about the number 22?

In Wago style counting, 20 is read はたち, so 22 is read はたち あまり ふたつ. It's 20 with a remainder of 2.

30 through 90 are easier because they work similarly to the Kango system, don't have special names, and follow a consistent pattern. For example, 30 is 3 (み) x 10 (そ), making it みそ. Then, you add the suffix for counting general things (ち) to make it みそち/みそぢ. Basically, it's the short Wago version of the first number, plus そ, plus the counter suffix ち.

We'll go through all the Wago numbers from 10 to 99. Then we'll take a look at the numerals 100 and above.

10 to 19

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 十 | とお/とを3 |

| 11 | 十一 | とお あまり ひとつ |

| 12 | 十二 | とお あまり ふたつ |

| 13 | 十三 | とお あまり みっつ |

| 14 | 十四 | とお あまり よっつ |

| 15 | 十五 | とお あまり いつつ |

| 16 | 十六 | とお あまり むっつ |

| 17 | 十七 | とお あまり ななつ |

| 18 | 十八 | とお あまり やっつ |

| 19 | 十九 | とお あまり ここのつ |

20 to 29

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 二十 | はたち |

| 21 | 二十一 | はたち あまり ひとつ |

| 22 | 二十二 | はたち あまり ふたつ |

| 23 | 二十三 | はたち あまり みっつ |

| 24 | 二十四 | はたち あまり よっつ |

| 25 | 二十五 | はたち あまり いつつ |

| 26 | 二十六 | はたち あまり むっつ |

| 27 | 二十七 | はたち あまり ななつ |

| 28 | 二十八 | はたち あまり やっつ |

| 29 | 二十九 | はたち あまり ここのつ |

The Wago counting method for 20 is はたち. This reading is still commonly used to refer to someone's age. 20歳 can be read as either にじゅっさい or はたち.

30 to 39

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|

| 30 | 三十 | みそち or みそぢ3/みそじ |

| 31 | 三十一 | みそち あまり ひとつ |

| 32 | 三十二 | みそち あまり ふたつ |

| 33 | 三十三 | みそち あまり みっつ |

| 34 | 三十四 | みそち あまり よっつ |

| 35 | 三十五 | みそち あまり いつつ |

| 36 | 三十六 | みそち あまり むっつ |

| 37 | 三十七 | みそち あまり ななつ |

| 38 | 三十八 | みそち あまり やっつ |

| 39 | 三十九 | みそち あまり ここのつ |

The Wago version of 30 is みそち or みそぢ (or the modern version is みそじ). This reading is still common when referring to someone who is 30 years old. It's written with the kanji 三十路 and usually carries a negative nuance that you are getting old.

You'll also see みそじ being used for the last day of December. It's called 大晦日 (おおみそか), which translates to "big miso day." You may be wondering why the 30th would be the last day of December, but remember that the old lunar calendar had 29 to 30 days per month.

Finally, you may run into 和歌 (わか) or 短歌 (たんか), classical short poems written in a 5-7-5-7-7 meter pattern. These are called 三十一文字 (みそひともじ), as the total number of 音 (which are like syllables… kind of) is 31.

40 to 49

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|

| 40 | 四十 | よそち or よそぢ3/よそじ |

| 41 | 四十一 | よそち あまり ひとつ |

| 42 | 四十二 | よそち あまり ふたつ |

| 43 | 四十三 | よそち あまり みっつ |

| 44 | 四十四 | よそち あまり よっつ |

| 45 | 四十五 | よそち あまり いつつ |

| 46 | 四十六 | よそち あまり むっつ |

| 47 | 四十七 | よそち あまり ななつ |

| 48 | 四十八 | よそち あまり やっつ |

| 49 | 四十九 | よそち あまり ここのつ |

The Wago for 40 is よそち or よそぢ. This reading actually still refers to people's age when they are forty. These days, it's written as 四十路 and read as よそじ. That being said, it's not as common as 二十歳 (はたち) or 三十路 (みそじ).

After 40, you won't see Wago readings for age at all.

50 to 59

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 五十 | いそち or いそぢ3/いそじ |

| 51 | 五十一 | いそち あまり ひとつ |

| 52 | 五十二 | いそち あまり ふたつ |

| 53 | 五十三 | いそち あまり みっつ |

| 54 | 五十四 | いそち あまり よっつ |

| 55 | 五十五 | いそち あまり いつつ |

| 56 | 五十六 | いそち あまり むっつ |

| 57 | 五十七 | いそち あまり ななつ |

| 58 | 五十八 | いそち あまり やっつ |

| 59 | 五十九 | いそち あまり ここのつ |

60 to 69

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|

| 60 | 六十 | むそち or むそぢ3/むそじ |

| 61 | 六十一 | むそち あまり ひとつ |

| 62 | 六十二 | むそち あまり ふたつ |

| 63 | 六十三 | むそち あまり みっつ |

| 64 | 六十四 | むそち あまり よっつ |

| 65 | 六十五 | むそち あまり いつつ |

| 66 | 六十六 | むそち あまり むっつ |

| 67 | 六十七 | むそち あまり ななつ |

| 68 | 六十八 | むそち あまり やっつ |

| 69 | 六十九 | むそちあまり ここのつ |

70 to 79

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|

| 70 | 七十 | ななそち or ななそぢ3/ななそじ |

| 71 | 七十一 | ななそち あまり ひとつ |

| 72 | 七十二 | ななそち あまり ふたつ |

| 73 | 七十三 | ななそち あまり みっつ |

| 74 | 七十四 | ななそち あまり よっつ |

| 75 | 七十五 | ななそち あまり いつつ |

| 76 | 七十六 | ななそち あまり むっつ |

| 77 | 七十七 | ななそち あまり ななつ |

| 78 | 七十八 | ななそち あまり やっつ |

| 79 | 七十九 | ななそち あまり ここのつ |

80 to 89

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | 八十 | やそち or やそぢ3/やそじ |

| 81 | 八十一 | やそち あまり ひとつ |

| 82 | 八十二 | やそち あまり ふたつ |

| 83 | 八十三 | やそち あまり みっつ |

| 84 | 八十四 | やそち あまり よっつ |

| 85 | 八十五 | やそち あまり いつつ |

| 86 | 八十六 | やそち あまり むっつ |

| 87 | 八十七 | やそち あまり ななつ |

| 88 | 八十八 | やそち あまり やっつ |

| 89 | 八十九 | やそち あまり ここのつ |

90 to 99

| Arabic | Kanji | Wago |

|---|---|---|

| 90 | 九十 | ここのそち or ここのそぢ3/ここのそじ |

| 91 | 九十一 | ここのそち あまり ひとつ |

| 92 | 九十二 | ここのそち あまり ふたつ |

| 93 | 九十三 | ここのそち あまり みっつ |

| 94 | 九十四 | ここのそち あまり よっつ |

| 95 | 九十五 | ここのそち あまり いつつ |

| 96 | 九十六 | ここのそち あまり むっつ |

| 97 | 九十七 | ここのそち あまり ななつ |

| 98 | 九十八 | ここのそち あまり やっつ |

| 99 | 九十九 | ここのそち あまり ここのつ |

That was easy, right? Once you've learned the first ten as well as the pattern, it's just a simple number-math riddle.

Wago and Counting to 100 and Beyond

Hitting 100 and above requires you to use the same pattern you learned before, with new unit names. 100 works like 10: when it's used by itself (100–199), it's read もも or ももち. When it's above 199, along with other numbers, it's read as ほ. 100 is ももち and 101 is ももち あまり ひとつ, but 200 is ふたほ, and 300 is みほ, etc.

Moving on to other units, 1,000 is ち and 10,000 is よろづ. They don't have different readings like 10s' そ and 100s' ほ, so 1,500 is ちいほ, 2,000 is ふたち, 15,000 is よろづいち, and 20,000 is ふたよろづ.

| Arabic | Old Reading | Modern Reading | Counting |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | もも | もも | ももち |

| 200 | ふたほ | ふたお | ふたほ(ち) |

| 300 | みほ | みお | みほ(ち) |

| 400 | よほ | よお | よほ(ち) |

| 500 | いほ | いお | いほ(ち) |

| 600 | むほ | むお | むほ(ち) |

| 700 | ななほ | ななお | ななほ(ち) |

| 800 | やほ | やお | やほ(ち) |

| 900 | ここのほ | ここのお | ここのほ(ち) |

| 1,000 | ち | ち | ち(ち) |

| 2,000 | ふたち | ふたち | ふたち(ち) |

| 3,000 | みち | みち | みち(ち) |

| 4,000 | よち | よち | よち(ち) |

| 5,000 | いち | いち | いち(ち) |

| 6,000 | むち | むち | むち(ち) |

| 7,000 | ななち | ななち | ななち(ち) |

| 8,000 | やち | やち | やち(ち) |

| 9,000 | ここのち | ここのち | ここのち(ち) |

| 10,000 | よろづ | よろず | よろづ(ち) |

| 20,000 | ふたよろづ | ふたよろず | ふたよろづ(ち) |

| 30,000 | みよろづ | みよろず | みよろづ(ち) |

| 40,000 | よよろづ | よよろず | よよろづ(ち) |

| 50,000 | いよろづ | いよろず | いよろづ(ち) |

| 60,000 | むよろづ | むよろず | むよろづ(ち) |

| 70,000 | ななよろづ | ななよろず | ななよろづ(ち) |

| 80,000 | やよろづ | やよろず | やよろづ(ち) |

| 90,000 | ここのよろづ | ここのよろず | ここのよろづ(ち) |

Idiomatic Usage of Wago Counting

The idiomatic Wago counting words that remain these days are basically 800 (八百/やお) and 10,000 (万/よろづ or よろず). They basically mean "a lot" or "many kinds," and you see them in words like these:

- 八百屋 (やおや)

- a fruit and vegetable store; a green grocery; literally, a store with all kinds of veggies and fruits

There's a Japanese term, 八百万の神 (やおよろず の かみ), that means 800,000 (800 x 10,000) gods. If you were watching closely, you may have seen reference to it in Spirited Away. In the film, all kinds of gods were living in the abandoned amusement park. Also, the main character's name is 千尋 (ちひろ). The kanji 千 means 1,000, and its Wago reading is ち. But her nickname was せん, the Kango reading for the same thing!

Another word uses 八百 (やお): 八百長 (やおちょう), which means a "fix" or "set-up." For example, you might say, "That game was a fix!" (あの試合しあいは八百長だ!). This word came about because of a man named 長兵衛 (ちょうべい), a green grocer (八百屋/やおや), who loved playing Go. He was very good at it, but apparently would intentionally lose games so his friends would feel bad and buy veggies at his store. One day he was invited to play against Hon'inbō Shūgen, whom he could battle evenly with. Because of this, people learned he was intentionally losing his games to them, and the word 八百長 (やおちょう) was born. It's an abbreviation of 八百屋の長兵衛 (やおやのちょうべい), and has come to be used to describe a fixed game, or a game where someone isn't being serious.

Gairaigo Counting

Finally, there is one last counting method I want to introduce you to: English.

ゼロ、ワン、ツー、スリー、フォー、ファイブ、シックス、セブン、エイト、ナイン、テン

We haven't broached this topic yet, since all the numbers are used fairly often (we referenced ゼロ a few times in the Kango section). Most Japanese people know the English words for numbers, at least 0 through 10, and you'll see them used in written form as well. Their pronunciation is different from that of traditional English, however. If you can read Katakana, you'll be able to see how it differs by reading the list of numbers above.

It's Time to Count Down…

Japanese speakers have been slowly transitioning their counting method from Wago to Kango since the late 1800s. Kango has gradually became more popular and, following World War II, fewer and fewer Japanese people count beyond 10 using the Wago method. By introducing how to count in Wago to you, the Tofugu readership, we have probably single-handedly tripled the worldwide population of people who can do it. And you are one of them!

With all that, you are almost a Japanese counting master. As we mentioned before, there is one big topic we haven't covered yet: Japanese counters (助数詞). But that knowledge will come with time (and more articles). For now, stick with it, and eventually you'll find your masterhood will manifest!

Counting in Japanese Study Spreadsheet

We put together a spreadsheet containing most of the numbers from this article. Upload them to your favorite SRS for study, or use it at the office since it'll look like you're working on that TPS report.

-

This is an archaic kanji and not commonly used today. Be aware that it exists, but don't expect it to come up in your daily life very often. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

そ is an old way of reading 十, and people don't use it today. Be aware that this reading exists, but don't expect it to come up in your daily life very often. ↩

-

This is an archaic spelling and not commonly used today. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8