Part 1: Where The Japanese Language Came From

English loanwords in Japanese are often a source of amusement for native speakers of English learning Japanese as a second language. There’s so many of them, it seems like if you don’t know a word in Japanese, you can just guess by taking the word in English, pronouncing it with Japanese sounds, and half of the time you’ll be right! How convenient! It’s true that there are a lot of English loanwords in Japanese, but the language has also absorbed vocabulary from plenty of other languages before English became all that and a bag of chips.

Just like most other languages (except maybe Klingon), Japanese is constantly in flux, slowly becoming a bigger and bigger amalgamation of several outside languages over time. Think Katamari Damacy: bits and pieces from other languages stick to the base language forming a giant mass of mis-matched BLAH (and yet, humans manage to communicate with each other).

But patterns of borrowing are not random. A language’s vocabulary is the reflection of the culture and history of its speakers, and Japanese is no exception. The distribution of foreign vocabulary is often concentrated in different fields, pointing to the significance of the relationship between the two nations (just as the borrowing of チーズバーガー shows the cultural significance of cheeseburgers in the relationship between the US and Japan). We can also observe changes in borrowing that have occurred through history.

Languages in Japanese

The Japanese language has come from many different sources in the past, and we can categorize Japanese words into three groups according to their origin: wago 和語, kango 漢語, and gairaigo 外来語. Wago are native Japanese words, while kango refers to Chinese loanwords and gairaigo to words borrowed from foreign countries other than China.

As stated above, the distribution of foreign vocabulary is often concentrated in different fields of interest. Looking at the relationships between Japan other countries through history can help us understand said focuses. But first, let’s take a closer look at the Japanese language before it became inundated with foreign vocabulary.

Wago 和語

Japanese: weather, fish, feelings, rice (lacking: body parts, domesticated animals, actions)

The term wago 和語, or Yamato-kotoba, refers to native Japanese words passed on from Old Japanese. Although wago did not come from abroad, it too reflects the cultural interests of its speakers, the Japanese.

Traditional Japanese society focused a lot of energy on farming and fishing, and the native vocabulary shows evidence of this fact. Have you ever wondered why there are so many words for weather in Japanese when all are you want to say is “there is water falling from the sky”? The native vocabulary is teeming with words related to weather, especially rain and water (this comes in handy in the Northwest), because it was important for rice farmers to know this stuff if they wanted to have successful crops and eat buckets of rice! There are also many expressions related to nature, crops, fish, rice, bodies of water, and senses/feelings. Take a look:

Wago Words for Rice

| English | wago 和語 |

|---|---|

| rice plant | ine 稲 |

| raw rice | kome 米 |

| cooked rice; meal | gohan ご 飯 |

| cooked rice; meal | meshi 飯 |

Wago Words for Rain

| English | wago 和語 |

|---|---|

| spring rain | harusame 春雨 |

| autumn rain | akisame 秋雨 |

| May Rain | samidare 五月雨 |

| rain during the rainy season | tsuyu 梅雨 |

| evening rain | yuudachi 夕立 |

| light rian | kirisame 霧雨 |

| passing shower; streaks of pouring rain | amaashi 雨脚 |

| taking shelter from rain | amayadori 雨宿り |

| rain cloud | amagumo 雨雲 |

Wago Words for Yellowtail (Fish)

| English | wago 和語 |

|---|---|

| yellowtail less than 6-9 cm | abuko あぶこ |

| yellowtail less than 6-9 cm | tsubasu つばす |

| yellowtail less than 6-9 cm | wakanago わかなご |

| yellowtail around 15 cm | yasu やす |

| yellowtail around 15 cm | wakashi わかし |

| yellowtail around 36-60 cm | warasa わらさ |

| yellowtail around 36-60 cm | inada いなだ |

| yellowtail around 36-60 cm | seguro せぐろ |

| yellowtail around 45-90 cm | hamachi はまち |

| yellowtail over 1 m | buri 鰤 |

| yellowtail caught during the cold season | kanburi 寒鰤 |

| large, purplish yellowtail | kanpachi 環八 |

And this is just the start… There are many, many, MANY more words in Old Japanese related to these topics; I haven’t even scratched the surface here. This just emphasizes how important agriculture was in traditional Japanese society. If you want to know more about Yamato-kotoba, I recommend reading Koichi’s article on the topic. Or, if you just really love rain, this article on Japanese rain words is really fun.

Although Japanese is overflowing with words on these topics, the language also had some pretty major holes in it before all of this globalization mishy-mashy cultural mixing started happening. This included body parts (ashi means foot and leg?), names for domesticated animals, and action words. But sooner or later, (dun dun DUN!) the foreigners arrived, and those gaps were slowly filled.

Kango 漢語

Chinese: abstract concepts and academia

Chinese has been such a huge influence on the Japanese language in past that it deserves its own classification. It’s believed that Japan was first introduced to Chinese words around the first century A.D. when Korean scholars brought Chinese books to Japan. That’s a long time ago! At first, Chinese was used mainly as a means of documentation and for academic writing, but eventually it became part of everyday Japanese lingo.

Kango makes up as much as 60% of the Japanese language. Because the source of some words isn’t so clear, even words that didn’t originate in China but are written with Chinese characters or use the Chinese reading are referred to as kango. In many ways, kango can be seen as a parallel to Latinate words in English. To this day, kango is mainly used for academic words and abstract concepts. So, these are the words you’ll be seeing a lot of in textbooks and scientific readings, and of course they are mostly written in kanji (Chinese characters)! Everyone’s favorite! Though, of course, there are many casually used kango as well. The differences between kango and wago can be seen when compared side-by-side:

| English | Wago 和語 | Kango 漢語 |

|---|---|---|

| yesterday | kinou 昨日 | sakujitsu 昨日 |

| language | kotoba 言葉 | gengo 言語 |

| play (fun) | asobi 遊び | yuugi 遊戯 |

Kango are a lot more literary and academic, so you won’t be learning a whole lot of them in your Japanese 101 class or using them in conversation (unless you really want to sound sophisticated, or perhaps just snobbish?). However, this is a really interesting point that I feel many classes fail to point out. The status of wago and kango in Japanese is very similar to Latin and German in English. Check it out:

| Germanic | Latinate |

|---|---|

| help | aid |

| hide | conceal |

| deep | profound |

These days, words borrowed from Chinese (and Korean) mainly fall under the categories of culturally specific items such as food. The majority of loanwords, however, come from English. What a change!

Gairaigo 外来語

Loan words coming from countries other than China are classified as gairaigo. More often than not, these words are written in katakana. These days, gairaigo are seen as stylish and cool, so you’re more likely to see them in something like Seventeen Magazine, rather than Popular Science.

Although foreign vocabulary is now dominated by English, there were times when this was not the case. Other countries, namely France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Russia, Portugal, and Spain, have claimed greater shares than English in the past, but I’ll only cover some of them here.

Note: Translations below are English translations of the Japanese terms, not of the native language in question.

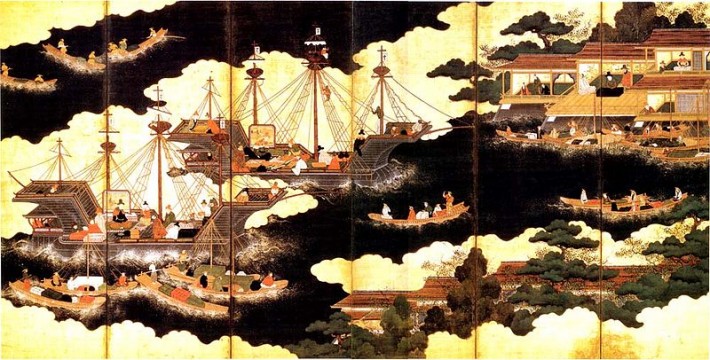

Portuguese: Christianity, “modern” technology, and Portuguese products

In 1542 the Portuguese became the first people to establish direct trade between Japan and Europe. Most Portuguese words entered Japanese through Jesuit priests who introduced the Japanese people to Christianity, Western science, and new products (like konpeito) throughout the 15th and 16th centuries. Therefore, most of the Portuguese words in Japanese have to do with the products and customs of the Portuguese people. Here are some words you might already know or might want to remember:

| ブランコ | balanço | swing |

| イエス | Jesus | Jesus |

| イギリス | inglês | England |

| かるた | cartas | cards |

| コップ | copo | cup |

| パン | pão | bread |

| 天麩羅 | tempero | tempura |

| タバコ | tabaco | tabaco |

| ボタン | botão | button |

| アルコール | álcool | alcohol |

| オランダ | Holanda | The Netherlands |

Dutch: medicine, sailing, and astronomy (oh my!)

Although the Dutch were not the first to make contact with Japan, they too had a huge impact on the Japanese language. In 1609, the Dutch East India Trading Company started trading with Japan, remaining the only Western country allowed to do so throughout Japan’s seclusion period (those lucky Dutch!). At one point, 3,000 Dutch words were commonly used in Japan (that’s more words than I know… in English), but that number has dwindled to 160 words used in the present day. Most Dutch loanwords are technical in nature, having to do with medical science and diseases (sharing is caring? I mean, oops.), astronomy, sailing, and beer! Yay, beer.

| ビール | bier | beer |

| ドイツ | Duits | Germany |

| ドロンケン | dronken | drunk (not really used, but cute) |

| ゴム | gom | rubber |

| ハム | ham | ham |

| ハトロン | patroon | pattern |

| カミツレ | kamille | camomile |

| コーヒー | koffie | coffee |

| メス | mes | scalpel |

| モルモット | marmot | Guinea pig |

| お転婆 | ontembaar | tomboy |

| ペスト | pest black | death |

| オルゴール | orgel | music box |

| ピストル | pistool | pistol |

| ピント | punt | focus point |

| ピンセット | pincet | tweezers |

| アロエ | aloë | aloe |

French: culture, diplomacy, and art

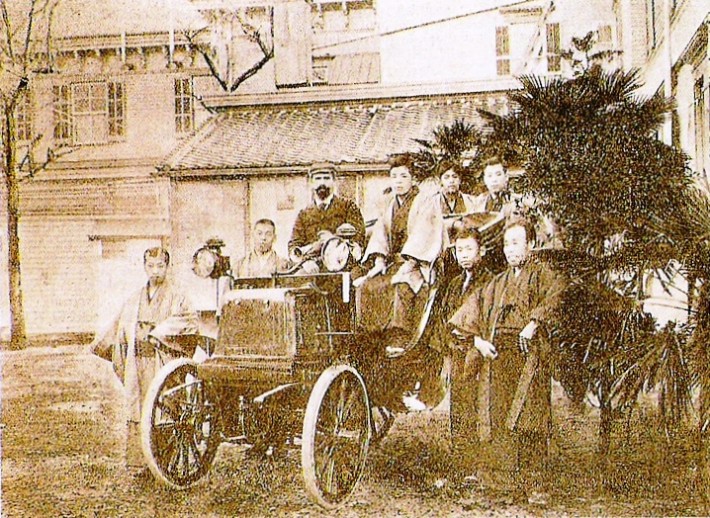

In the late 1800’s, English replaced Dutch as the language of foreign relations. French was also studied heavily during this time due to its status as an international language in the fields of diplomacy and culture during Japan’s Meiji Restoration period. A lot of French words have to do with art and fashion, as you might expect (ooh la la!):

| アベック | avec | romantic couple |

| アンケート | enquête | questionnaire; survey |

| アンニュイ | ennui | boredom |

| バイク | bike | motorcycle |

| バリカン | Bariquand & Marre | barber’s clippers |

| デッサン | dessin drawing | rough sketch |

| エスカレーター | escalator | escalator |

| コンクール | concours | a contest |

| コント | conte | a funny story |

| マロン | marron chestnut | brown eyes |

| マゾ | masochiste | masochist |

| ズボン | jupon | pants, trousers |

| ゼロ | zéro | zero |

| サボる | sabo(tage) + -ru (Japanese verb ending) | to skip class, to goof off |

| ルポ | repo(rtage) | reportage |

| ロマン | roman | novel, romance |

| レストラン | restaurant | restaurant |

| ピーマン | pīman | bell pepper |

| ピエロ | pierrot | clown |

| ペンション | pension | a resort hotel, cottage |

German: medical science and sports

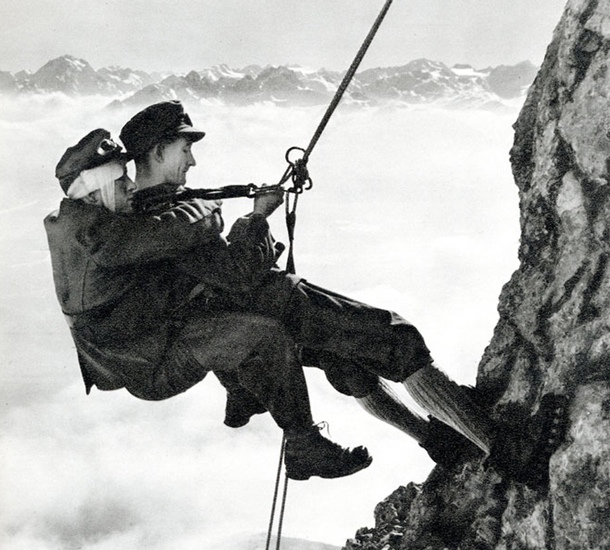

French wasn’t the only language studied in Japan during the Meiji period. After Japan opened its doors to the West in 1868, many Germans moved to Japan in order to work in the new government as foreign advisers. During this time, the Germans contributed many terms to the fields of medical and military science. Japanese also absorbed many sports related words from German, many of them involving mountain climbing.

| アイゼン | eisen | crampons, metal pins of climbing shoes |

| ピッケル | (eis)pickel | ice axe |

| ザイル | seil | climbing rope |

| アルバイト | arbeit | part-time job |

| エネルギッシュ | energisch | energetic |

| ガーゼ | gaze | gauze |

| ゲレンデ | gelände | ski slope |

| ギプス | gips | cast |

| ヒステリー | hysterie | loss of self control; hysteria |

| ホルモン | hormon | hormone |

| カルテ | karte | medical record |

| オペ | operation | surgical operation |

| レントゲン | röntgen | X-ray |

| リュックサック | rucksack | backpack |

| テーマ | thema | theme |

Of course, loanwords have been taken from many other languages, too; these are some of the major ones. Other languages that have contributed substantially to Japanese include Ainu, Russian, Spanish, Korean, and Italian. Below I’ve listed a few more miscellaneous gairaigo, just for the fun of it.

| イクラ | ikura | salmon roe (Russian) |

| ノルマ | norma | quota (Russian) |

| ラッコ | rakko | sea otter (Ainu) |

| トナカイ | tunakkay | reindeer (Ainu) |

| パンツ | pants | underwear (British English) |

| ロマンスグレー | romance grey | silver-grey hair (British English) |

| ウィンカー | winker | turning signal (British English) |

| アメリカンドッグ | American dog | corn dog (British English) |

| ライフライン | lifeline | infrastructure (British English) |

| パパ | papa | dad (Italian) |

As you can see, the vocabulary of a given language is determined by the cultural interests of its speakers, and the loanwords a language absorbs depends strongly on the nature of the connections between the two communities involved. As globalization continues to happen, more and more words are being adopted and traded. Who knows what language we’ll be speaking tomorrow. I hope it’s Klingon.

Learning Japanese by source is not only fascinating, it can be a good way to form connections in your mind so you can remember words better! At least, that’s worked for me.

Part 2: Twisting Words

The phenomenon of language borrowing is in no way unique, but it seems to stand out more in the Japanese language than others. And in a way, this presumption is true. Japanese has adopted an astounding number of loanwords. Even the written language, consisting of 3 distinct writing systems, gives way to the amount of borrowing that has gone on over the centuries.

However, borrowing, especially from English, has become even more exaggerated in the post WWII era, almost certainly kicked off by the occupation period. Loanwords are everywhere in Japan. They’re like air. You can’t get away from them.

But are they air? Or are they a pollution in the air? That is the question asked by many people in Japan. Taking in loanwords at such a rate has not been a trouble-free, clean-cut process. In fact, so much borrowing has created a bit of a sticky mess in the language; the whole process has rendered many words elusive to both second language learners and native speakers alike.

Borrowing: A Linguistics Perspective

So how has Japan, a relatively isolated country with its own distinct language, been able to borrow foreign words at the rate they have? Actually, Japanese has certain linguistic characteristics that have made borrowing much easier than some other languages.

The main reasons why Japanese has accepted foreign words so easily has to do with the lack of nominal inflections and the presence of a syllabary writing system. In other words, Japanese nouns do not change based on person, number, or gender like many other languages do, and since words are simply separated syllabary particles, it makes it easy to just plop a foreign word in the midst of a Japanese sentence where any native word might appear. As for adjectives and verbs, foreign words can be inserted as な (na) adjectives and する (to do) can convert anything into a verb without any changes to the original word. Magic! (I always wondered why there were so many な adjectives and する verbs in Japanese.)

So, foreign words have had an easy time slithering their way into Japanese language from a linguistics perspective, but that hasn’t stopped them from wreaking havoc across the land in their own special way, plaguing both Japanese learners and native speakers.

Making Changes

You’d think with number of foreign loanwords floating around in the language, Japanese would sound slightly less like “moon speak” to non-Japanese speakers. However, foreign loanwords have been warped and maimed beyond the point of recognition in many cases, making understanding Japanese all the more frustrating!

When a foreign word is adopted in Japanese, it goes through many changes (like a beautiful butterfly). First of all, loanwords are converted to Japanese characters (usually katakana), changing their pronunciation altogether. On top of that, the meaning of a word may shift, a word may be simplified, and sometimes words will even be completely invented! For me, it is particularly upsetting when I think I understand a loanword from English, when actually I don’t know squat. Basically, I can’t even understand my own language in Japanese a lot of the time. Yep. Let’s take a look at some of the changes foreign words have undergone to become a totally different animal.

Changes in Meaning

Changes in meaning often happen in the process of foreign borrowing. The meaning of a word may be narrowed, widened, specialized, shifted, downgraded, you name it. At this point, I’ve come to believe that it’s someone’s job to sit in an office and figure out the best way to mutilate the English language before it enters Japan. Honestly, I really want that job.

Narrowing and Specialization

When a word’s meaning is narrowed or specialized, only one aspect of its original meaning is adopted as the new loanword. So in other words, a word that originally has a more general meaning is changed to mean something very specific.

| Examples | ||

|---|---|---|

| ホテル | hotel | Western-style hotel |

| ステッキ | stick | cane |

| ライス | rice | rice served on a plate |

| アルバイト | work | part-time job (usually student) |

| ダイエット | diet | purposely losing weight |

| ストライキ | strike | demonstration, strike |

| ストライク | strike | strike (in baseball) |

| ゲイ | gay | relationship between men only |

| ドレス | dress | extravagant dress |

Extension

The widening of a word’s meaning is not nearly as common as narrowing, but it does happen. In these cases, a word’s meaning is more generalized, or used to describe a broader range of ideas.

| Examples | ||

|---|---|---|

| レジ | register | cash register, cashier |

| ハンドル | handle | car steering wheel, bike handlebar, any other handle |

Shifts in Meaning

It’s a fairly common occurrence for a word’s meaning to be shifted when it is enters another language. This means that the original meaning of a word is completely changed, and all hope of the foreign language’s speakers understanding it is lost. “What? サイダー (cider) means soda?!” Check it out:

| Examples | ||

|---|---|---|

| アベック | avec (with) | a romantic couple (old saying) |

| フェミニスト | feminist | a man who indulges in women; a gentlemen |

| マンション | mansion | large apartment complex |

| アイス | ice | ice cream |

| カニング | cunning | cheating |

| バイキング | Viking | all-you-can-eat-buffet |

Of course, out post about wasei eigo goes over even more examples.

Downgrading

The meaning of a word can sometimes be downgraded, too. Downgrading is the lowering of importance or rank in terms of the social significance a word holds.

The examples below clarify this phenomenon.

| Examples | ||

|---|---|---|

| ボス | boss | the head of a group of politicians or gangsters |

| マダム/ママさん | Madam/mother | owner of a drinking establishment |

Inventing Words

Just as many words were created in Japan from Chinese characters in the past, today many new “foreign” words are just inventions. I don’t know about you, but the concept of new English words being created in another language makes me feel both amazed and downright strange.

Often times new foreign words are created in Japanese by combining two or more already existing terms to make a completely new one. Sometime only parts of words such as the -er suffix are used. Some of the most bewildering words are invented by creating acronyms from foreign phrases. As you can imagine, this renders “foreign” words completely unrecognizable to speakers of the word’s language of origin. Mama mia! Invented words are so numerous, it would be insane to list as many as I could here, but here’s a nice sampling:

| バックミラー | back + mirror | rearview mirror |

| テーブルスピーチ | table + speech | dinner speech |

| オーエル | OL | office lady |

| オールドミス | old + miss | an old, childless woman |

| ヘルスメーター | health + meter | a bathroom scale |

| ソープランド | soap + land | a brothel |

| アイスキャンディース | ice + candy | popcicle |

| マイホーム | my home | a privately owned home |

| マイカー | my car | a privately owned car |

| パートタイマー | part-timer | someone who works part-time |

| ナイター | nigher | a night baseball game |

Simplification

Taking words directly from another language is often times not the most convenient thing, especially when the word is 100 letters long and no one can pronounce it (antidisestablimentarianism? Riiiiighht). So, why not make it shorter? The Japanese have a tendency to shorten words more so than other languages. Four syllable abbreviations seem to be preferred, but you may also see other variations.

| Examples | |

|---|---|

| アルミカン | aluminum can |

| セクハラ | sexual harassment |

| プリクラ | print club (purikura) |

| テレビ | television |

| トイレ | toilet |

| パソコン | (personal) computer |

| リモコン | remote control |

| エアコン | air conditioner |

| デジカメ | digital camera |

| ワープロ | Word processor |

Confusion at Home

If learning loanwords is confusing for foreigners, it’s really not that much better for the Japanese population themselves. Since foreign loanwords are not written in Chinese characters anymore, Japanese people can’t easily guess their meanings if they don’t already know them. On top of that, foreign words are being poured into Japan at such a rate that even natives don’t understand them anymore. It is also difficult to learn these words because they are often introduced and then dropped faster than a hot potato, leaving no time for full absorption into the language.

NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) conducted a multiple choice survey to see just how well foreign adopted words are understood by people in Japan. The results turned out to be very mixed and depended largely upon respondent groups. In other words, comprehension of foreign words depends largely on factors such as educational and occupational background. The survey also showed that foreign words were mostly understood in their Japanized forms, not in the context of their language of origin. It’s no wonder learning English can be difficult for Japanese students, they know a completely alternate version of it!

Movements have been made (mainly by angry old men) to stop the flow of foreign words into Japanese at the rate it’s been happening, but the madness continues. Stopping such a formidable force is no small feat, and language purist are undoubtedly fighting a losing battle as the “foreigners” take hold of their language. In fact, one 71 year old tried to sue NHK Broadcasting for the “mental distress” caused upon him because of all these foreign words.

But, when foreign words are being adopted, abandoned, changed, and invented the way they are in Japan, it really begs the question: “what is a loanword?” Can I call “back mirror” an English loanword? I honestly don’t know anymore.

Part 3: Why They Do It

So now you know that Japanese has become overwhelmed with English vocabulary, especially in the years following WWII. And when I say “overwhelmed” with English words, I don’t just mean there are a lot of them. I mean they are everywhere in Japan- staring you down and mocking you every way you turn. You can’t hide. They’re watching you.

At first, this fact was easy for me to just accept, even if it wasn’t what I expected Japanese to be (Free English words? score!), and it’s not especially apparent to residents of Japan who are surrounded by it everyday.

But, have you ever wondered why there are so many English words lurking about in Japan like a bunch of drunk party crashers?I mean, who invited them there anyway when Japan has a perfectly good language of its own? I’ll tell you why. The motivation for absorbing so many words from other languages can be broken down into four categories: compensation, upgrading, obscuring, and humor.

Compensation and Modernization

“Compensation” is probably the most obvious reason for stealing (I mean borrowing) words from foreign languages. In terms of linguistics, compensation has to do with absorption of foreign loanwords into the areas of a language where vocabulary is not yet developed or does not yet already exist. Since languages start off with an abundance of vocabulary in some fields, and a lack of vocabulary in others, it’s only natural that with language contact and the introduction of new cultural concepts, things get traded.

After Japan’s isolation period ended in 1868 and the doors to trade with the West were finally (forced) open, Japan had a lot of “catching-up” to do. With the trading of new goods from aboard, a whole heap of Western and technical terminology breached the floodgates. Then, with the American occupation during the years following WWII, Japan was heavily influenced by the ‘Murican forces – Japan was going to learn the word for cheeseburger whether they liked it or not! Of course, this introduced a whole slew of other words and ideas to the language that had never been present before. One of them was probably type 2 diabetes.

Okay, so it’s pretty obvious that English loanwords have often compensated for gaps in the Japanese vocabulary (spoon, fork, knife) and vice versa (sushi, tsunami, rickshaw). But, what about the cases in which a foreign word is adopted where a perfectly good native Japanese word already exists? This is where things get interesting – and complicated.

As you may have noticed, the rate at which Japanese has absorbed loanwords has resulted in a number of synonyms in the language, making it all the more frustrating for learners. I realize English is even worse, but seriously, does there have to be 6 words in the dictionary for everyone one I look up (Eeny, meeny, miny, moe, catch a tiger by his toe?). Yes, it does seem ridiculous, but there are reasons for everything.

Let me Upgrade You

Just as Kango, or words of Chinese origin, can have a classical, academic effect in the Japanese language, Western-based terms, especially from English, have effects of their own. One of these effects is social upgrading.

Due to a mess of political and cultural influences over the years, the English language is often regarded with a sense of elitism and prestige in Japan (though, sometimes it’s the opposite). Therefore, upgrading in this case refers to the social benefits received by using English loanwords in Japanese. In other words, using English vocabulary is a way of building one’s social image and making others say “Oh you fancy, huh?”

One example of this is using technical English terminology to sound as if you know something special and high-level. It’s sort of the same thing old Victorian era men did when they threw in random French words as if everyone knew French. I suppose since everyone is graded on their English skills in school, it’s almost like being really good at a subject like math in the US… sort of.

If it’s true that English carries an air of prestige, then it’s only natural that advertising companies would eat this stuff up (they have to sell you stuff so you can be cool, of course). Countless companies in Japan have created English advertising campaigns in an attempt to make their products look high-class, or “swag” as you kids say. And since commercials have such an influential force over the very flexible minds of young whippersnappers, English has become the coolest of the cool (it’s just so ironic).

Consequently, more and more English words have flooded the Japanese pop culture scene in recent years. However, because English is obviously not the native language of Japan, this has resulted in some pretty hilarious and downright confusing situations.

Although social upgrading is not the primary motivation for adopting English loanwords, it is especially associated with communication between youth and in the commercial realm.

Obscuring the Facts

English loanwords are not absorbed solely for fashion purposes. When I asked my Japanese friend Yuri how she felt when hearing English loanwords, she said:

“English words make everything sound blurry and vague.”

It happens in every language; foreign words are used to cover-up unpleasant or taboo ideas. Using a foreign word in place of a native one has the effect of obscuring the meaning, therefore blunting the force of said word. So, just as I can yell “scheiße!” in an American grocery store surrounded by elderly women without turning too many heads, people in Japan could potentially get away with advertising a big ‘ol F-bomb on their knickers.

That’s one classy granny. Now, an older woman in a “fart” shirt might seem innocent enough – just another helpless victim of marketing – but there are times when loanwords are used for less reputable purposes.

Rebel Yell

Angsty teenagers and rebels everywhere have their own way of sticking it the man, and language is usually a part of that. Japanese people who fit into this “rebellious” category often try to put themselves out of the mainstream by using language opaque to outsiders, and what better way to do that then to confuse everyone with English?

Using English as a rebellious language works in two ways: 1) instead of using it in a positive context, English words are usually selected to refer to negative ideas, and 2) the English language is sometimes mangled and warped to fit a particular group, separating it completely from standard usage.

For example, トラブる or トラブする means to make trouble, ペーパー (paper) means counterfeit money, and アド (address) refers to a hidden location. Graffiti written in romanized characters can also be found spewed all over the cities, giving the same effect of obscurity. Much of this has to do with creating in-groups and keeping social distance from the “majority.” Like man, if you don’t know yo street language, you be dissin’ yo homies. Word.

My English subtitles are so street, man.

Don’t Feel Guilty

Another effect English loanwords have is the diminishing of guilt associated with taboo subjects by creating euphemisms or codes. An interesting example is DCブランド. The original meaning of this phrase is “discount on name brand goods,” but it’s come to refer to students whose grades are primarily low Cs and Ds. Oh, the scandal! Money lending companies also like to take advantage of the vagueness of English words. “Money loan? Oh, that doesn’t sound so bad.”

Another example of this would be the words “hug” and “kiss” in Japanese. Have you ever wondered why English loanwords are used in these situations when obviously hugs and kisses weren’t imported from the UK or America (or were they)? Of course, these words do exist in Japanese, but over time their English counterparts have replaced them as common use words. According to my friend Yuri:

“If someone says せっぷん (kiss) or ほうよう (hug) in Japanese, I think everyone would be like, ‘Huh?! What happened?!'”

So, the Japanese words for hug and kiss sound very heavy and serious, while their English counterparts sound less like a dramatic scene in a K-drama and more like a good pat on the back. Good to know. If you think about English, “taboo” words are disguised all the time, too – especially by widely giggling junior high students. Giggity!

Be Polite!

Obscuring the truth is not always a bad thing. I mean, do you really have to tell your girlfriend that in fact, yes, her butt does look ginormous in those pants? In Japanese, using the English counterparts to native terms can sometimes be polite. For example, if you want to say copulate in Japanese, using “エッチ (ecchi, or H)” is a nicer way to do so, and saying “toire トイレ” instead of “benjo 便所” is always a good choice if you want to save your poor grandmother’s ears from your blasphemous mouth.

My friend Yuri gave a great example of this concept, too:

“When I don’t like something I can just say: ‘この部品はスタンダード (standard) から外れているかな’ (kono buhin wa sutandaado kara hazureteiru kana, “I wonder if this part is lacking something…“)

“Standard,” huh? Sounds pretty vague to me. During the interview she went on to describe how even her sociology textbook is filled with indirect English terms, used to avoid being overly harsh on touchy subjects. One of the chapter titles in her sociology textbook was: ネガティブなまなざしを感じ取るースティグマ化 (negatibu na manazashi wo kanjitoru – sutigumaka, Looking at negative perceptions – a changing stigma). If you’ll notice, the words “negative,” and “stigma” are both in English. If you try looking over some Japanese material, you might notice this trend.

Have Some Humor

The last use of English loanwords in Japanese I will touch briefly on is humor. Although it can be difficult to understand humor in other cultures, making fun of other languages is always a classic. However, since English is studied by all students in Japan, it’s a special case. Comedians love to twist the language and make it sound even stupider. For example, one comedian gets laughs by attaching the Japanese honorific “o” to plain loanwords like “juice.” Apparently the ridiculousness of the whole thing is a real gut-buster (I don’t get it).

The use of loanwords in Japanese is very complicated, and this is no way an exhaustive list of uses. However, getting a feel for the flavor English loanwords have in the language is a great way to better understand Japanese, especially when it comes to all those synonyms (and maybe even some Japanese humor). Although this “Westernization” of the Japanese language has been strongly criticized in recent years, all societies have their own ways of expressing social issues through language, and I happen to find the case of English loanwords in Japanese especially mind blowing.