How do you say "open" in Japanese? While you might expect a simple little verb like this would have a simple little translation, that's not quite the case. Japanese has four different "opens" — 開ける (akeru), 開く (aku), 開ける (hirakeru) and 開く(hiraku). To make matters worse, they all use the same kanji.

Japanese has four different "opens" — あける / あく / ひらける / ひらく

If this seems absolutely bonkers to you, take a minute to think about all the different meanings and uses of "open" in English. For example, you can open a door or window, or you can open a bottle or container. Beyond that, a shop could be open, and the bud of a plant can open up to reveal a beautiful blooming flower. I guess "open" isn't so simple after all.

In a similar fashion, in Japanese, these four verbs for saying "open" describe different kinds of openings. In this article, we'll cover each verb in detail, so that you understand which one is used in different contexts and why. Ready to open your mind? Here we go!

Prerequisites: This article assumes you already know hiragana and katakana. If you need to brush up, have a look at our Ultimate Hiragana Guide and Ultimate Katakana Guide. Although we begin with the most basic concepts, you'll get the most out of it if you have already encountered 開ける, 開く, 開ける and 開く before and you're ready to dive into the the differences between them.

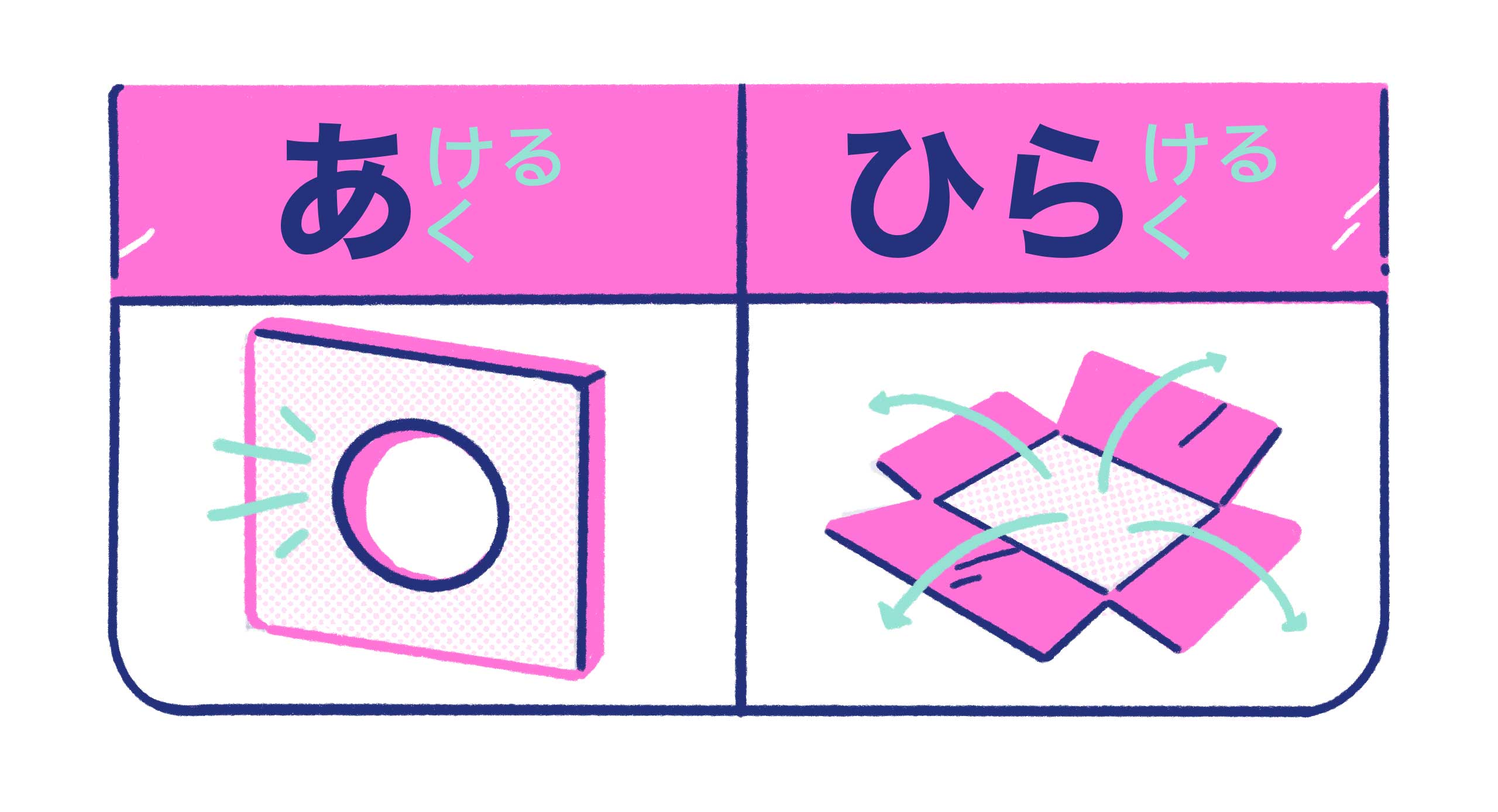

あ〜 VS ひら〜

Let's start by looking at the readings of this kanji. You'll notice 開ける (akeru), 開く (aku), 開ける (hirakeru) and 開く (hiraku) can be broken up into two different categories. That is, two of them begin with the reading あ (a) and the other two begin with ひら (hira).

Simply speaking, the ones with あ ( 開ける, 開く) are used to describe versions of "open" that result in a vacant physical space, such as making a hole in an object.

So, to talk about making a hole in an ordinary wall, you'd use 開く and say:

- かべに穴が 開く。

- A hole is made in the wall.

(Literally: A hole is opened in the wall.)

Or, you'd use the other half of the pair 開ける and say:

- かべに穴を 開ける。

- I made a hole in the wall.

(Literally: I open a hole in the wall.)

On the other hand, the ones with ひら ( 開ける and 開く) describe "open" in a more three-dimensional way, like when spreading out or unfolding something.

So, to talk about a flower bud unfolding, you'd use 開く and say:

- つぼみが 開く。

- A bud opens.

This is because when a flower blooms, it involves the petals spreading outward from the center. The focus is on the idea of three-dimensional movements, so 開く is more suitable.

開ける is less common than the other three "opens," and it's generally used figuratively, carrying a much more formal tone. 1 However, the same logic still applies.

For example, one of the figurative meanings of 開ける is "becoming civilized/modernized," as in:

- 町が近代化された都市に 開ける。

- The town develops into a modernized city.

Since the word begins with ひら, it describes the physical movement of opening up or unfolding, rather than the action of creating an empty space. For this reason, it can be used for metaphorical "openings" like an old-fashioned town expanding and rolling out new, modernized infrastructure.

So those are the differences between the opens that begin with あ and the ones that begin with ひら! It's pretty straightforward, right?

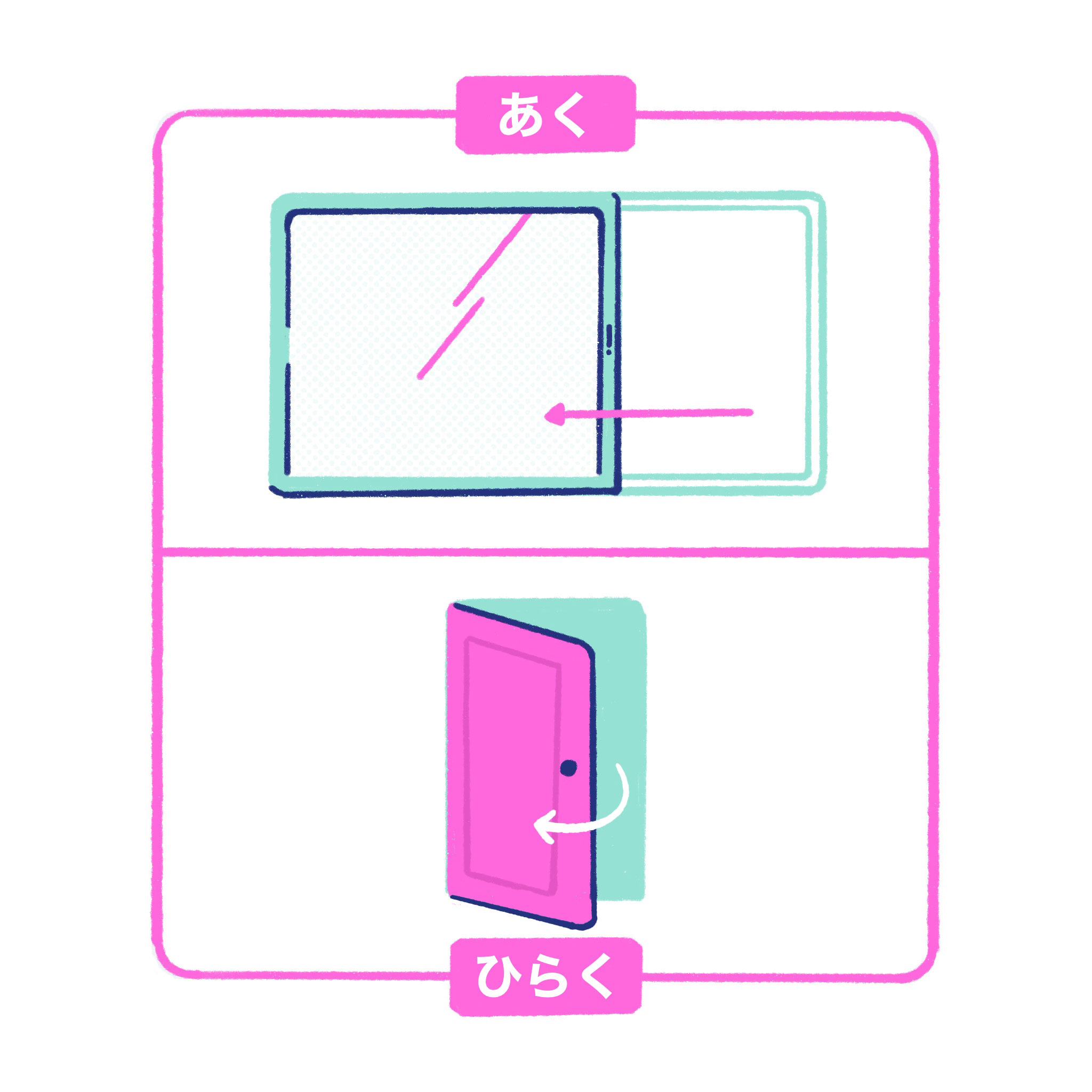

That being said, when you see this kanji in a sentence, it may be difficult to understand which meaning or reading is being referred to. For example, to talk about the opening of a hinged door, you can use either 開く or 開く and say:

- ドアが 開く。

ドアが 開く。 - The door opens.

Although the difference is subtle here, the same concepts still apply. That is, 開く simply indicates space is being created by removing an obstacle (the door). On the other hand, 開く's focus is more on the trajectory of the door movement, which results in the creation of an opening.

Hence, when talking about sliding doors, 開く is more suitable because it doesn't involve any physical "unfolding" movement. If you use 開く instead, it could sound as though the space on the other side of the door has been revealed to you. It could show your excitement to see the path or space beyond the doorway once it's been revealed. 2

To see how this difference applies to various uses, we'll go through a number of examples. But before that, there is one more thing we need to explain — the difference between the two versions of each pair, namely, 開ける vs 開く, and 開ける vs 開く.

The Kanji 開 and Transitivity

So, why are there two versions of "open" in each pair, and what's the difference between them? To understand this, let's first take a look at the kanji for "open" — 開.

The kanji 開 consists of 門 and 开. Both components come from pictographs, and while 門 represents "a gate," 开 has two possible origins. The first theory suggests 开 consists of "一," or a bar for a gate, and two 十s (as in 十 十), which represent two hands. Putting the pictographs together, 開 shows two hands pushing open a barred gate. The second theory suggests 开 can be broken up into two 干s (as in 干 干), which represent two people of equal height, to show the gate is opened equally and together.

We don't know which theory is closer to the origin, but it seems that both are important, particularly because they are perfect for describing this pair — 開ける and 開く.

開ける and 開く are a so-called transitivity pairs. That is, 開ける is a transitive verb, or 他動詞 ("other" verb), and 開く is an intransitive verb, or 自動詞 ("self" verb).

What are transitive verbs and intransitive verbs? To put it simply, transitive verbs describe an action that involves the transfer of force from a subject to an object.

So, to describe someone (the subject) opening something (the object), you would use the transitive verb 開ける, as in:

- 王子が門を 開けた。

- The prince opened the gate.

Transitive verbs describe an action that involves the transfer of force from a subject to an object.

In this example, 王子 (the prince) transfers his force to the gate, causing it to open. It can be by either physically pushing the gate open, or by ordering his servant to do so, but either way, the focus is on how he causes the gate to open with his own power.

On the other hand, the action described by intransitive verbs doesn't focus on the transfer of energy from a subject to an object. Instead, it pays more attention to the change in the subject itself, like:

- 門が 開いた。

- The gate opened.

In this sentence, the focus is simply on the fact that the gate opened and not who or what opened the gate. You can still add things like 風で (by the wind) or 王子の命令で (by order of the prince) to show how or why the gate was opened, but still, the focus is on what happened rather than on who made it happen.

The focus is on what happened rather than on who made it happen.

So going back to the two pictograph theories, the one with two hands pushing the gate is like the transitive open, or 開ける. Someone is transferring their force on the gate to open it. And the other one is like the intransitive open, or 開く. Two people are passing through the gate that is open for them. The gate may have been opened by themselves or someone/something else, but with 開く, the focus is simply on what change occurred to the gate — it opened.

So far, so good? Now, let's take a look at another pair — 開ける and 開く. As you might have guessed, they are also a transitivity pair. 開ける ends in 〜ける just like the transitive verb 開ける, while 開く ends in 〜く just like the intransitive verb 開く. You might then guess that 開ける is transitive and 開く is intransitive. But you'd be wrong! Despite the resemblance, 開ける is intransitive and 開く can be either transitive or intransitive. Why language gotta be that way though? 🙄

Since 開く can be either transitive or intransitive, you can say:

- 王子が門を 開いた。

- The prince opened the gate.

- 門が 開いた。

- The gate opened.

In the first example, 開く is used as a transitive verb, focusing on the transfer of the prince's force to the gate, causing it to open. The second example uses 開く as an intransitive verb, meaning the focus is only on the change of the subject, or what happened to the gate.

And as we learned in the previous section, the difference between " 開ける and 開く" and " 開く" is that the former is more about space being made, while the latter is more about the motion of the gate opening up.

Lastly, 開ける is an intransitive verb, so whenever it’s used, the focus is on the change that occurs in something rather than who makes the change. For example, 開ける can be used when a new road, railroad, or airway has been created, as in:

- シアトル—ポートランド間に、鉄道の新ルートが 開けた。

- A new railway route has been opened between Seattle and Portland.

In this sentence, you can see the focus is not on someone making the new railway but on the change itself. That route didn’t exist before, but now it has opened.

Comparison of Uses

So far, you’ve learned the basic differences of each Japanese "open." Now it's time to explore more examples for a better understanding. We'll start with the comparison of two transitive verbs, 開ける and 開く, and then move on to the two intransitive verbs, 開く and 開く. Finally, we'll take a look at a couple more examples of 開ける.

開ける VS 開く

First, we’ll compare 開ける with 開く when used as a transitive verb. As a refresher, 開ける begins with あ, so it focuses on the making of an opening. On the other hand, 開く begins with ひら, and so it focuses on the movement of spreading out. Now, let’s see why one word is chosen over another or how they are different when used in the same context.

Imagine you order a new desk, which you have to assemble by yourself. When it arrives, you notice the tabletop doesn't have holes for screws, and so you'll need to create them by yourself. To describe this situation, only 開ける works:

- 自分で穴を 開ける必要がある。

- I need to drill the holes myself.

This is because what you are describing is making openings on a surface. It doesn't involve any physical movements related to opening, so 開く is not suitable. 3

Next, imagine you were very thirsty and ordered a bottle of beer. To open the bottle, 開ける is your best option:

- ビール瓶を 開けた。

- I opened the beer bottle.

あける begins with あ, so it focuses on the making of an opening. On the other hand, ひらく begins with ひら, and so it focuses on the movement of spreading out.

In this example, what you are describing is creating an opening to drink the beer. If you use 開く, it would sound as though the bottle had a hinged lid that could open and close, but that's not the case with typical beer bottles. If you are talking about the lid of a water bottle with a pop-up straw though, 開く can also come into play as they often involve an unfolding movement.

Let's move on to the next situation. You are on a train, sitting tightly squeezed among the other passengers. At one stop, a man hops on and sits right next to you, and annoyingly manspreads his legs wide apart. For the "opening" of his legs, you'd use 開く, as in:

- 男は足を 開いて座った。

- The man sat with his legs open.

Here, 開く fits because it's about the movement of spreading out his legs.

Now, let's say this man takes a newspaper out of his bag, opens it up, and brings it obnoxiously close to your face. In this case, 開く is used again because the focus is on the "unfolding" of the newspaper. 4

- そして、男は新聞を 開いた。

- Then, the man opened up his newspaper.

Are you getting the hang of how 開ける and 開く are used? The next example is for when you can use both words, but the meanings will change slightly depending on which word is used.

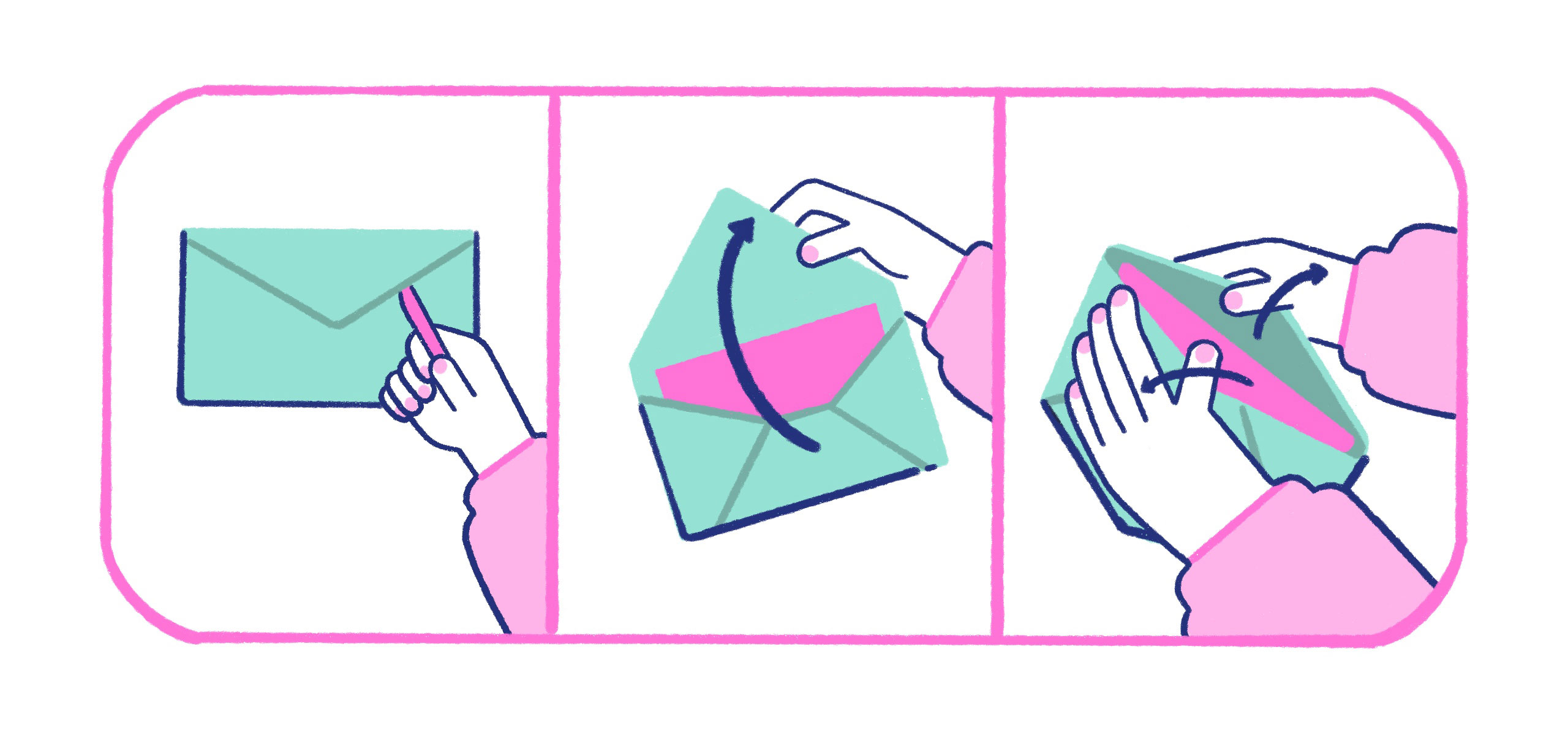

The example that illustrates the different nuances well is opening an envelope. When you say "opening an envelope," there are three different parts of the process: breaking the seal, unfolding the flap, and widening the opening of the envelope.

Whether you are cutting the envelope open with a paper-knife or scissors, or just ripping it open, if you are simply describing the unsealing of the envelope, 開ける is normally used.

- 封筒を 開けた。

- I unsealed the envelope.

Here your focus is on creating an opening so that the content inside becomes accessible. You're not depicting a physical movement like that of unfolding or spreading out. On the other hand, if you are talking about lifting the flap you just opened with your paper-knife, then 開く can be used.

- 封筒を 開いた。

- I opened the flap of the envelope.

In this example, the "open" you are describing is more about the unfolding of the flap. So unless you are still metaphorically talking about creating an accessible opening, 開く is your choice.

Lastly, you can also use "open" when you widen the mouth of the envelope to better reveal what's inside. Perhaps it's a paycheck you are waiting for, or a mysterious letter from a secret admirer. Whatever it is, this "widening of the opening" can take either 開ける or 開く, as in:

- 封筒を 開けた。

封筒を 開いた。 - I widened the opening of the envelope.

When using 開ける, it focuses on creating a space to peer into or to grab the content inside. On the other hand, 開く emphasizes the movement of widening the opening.

When not referring to the physical movement of opening something, the differences may be less obvious, but the same concepts still apply. For example, you can use 開ける and 開く for opening a store. However, while 開ける means to open a shop at the start of a business day, 開く means to start a new business.

- 店を 開ける

- open the shop (as in opening for the day)

- 店を 開く

- open a shop (as in starting a business)

In the first example, 開ける is used because it's referring to unlocking the door and allowing customers to come into the space inside. The second example, on the other hand, uses 開く because it's like describing how your budding business idea is unfolding into an actualized entity. The story of your business is finally starting to unfold.

開く VS 開く

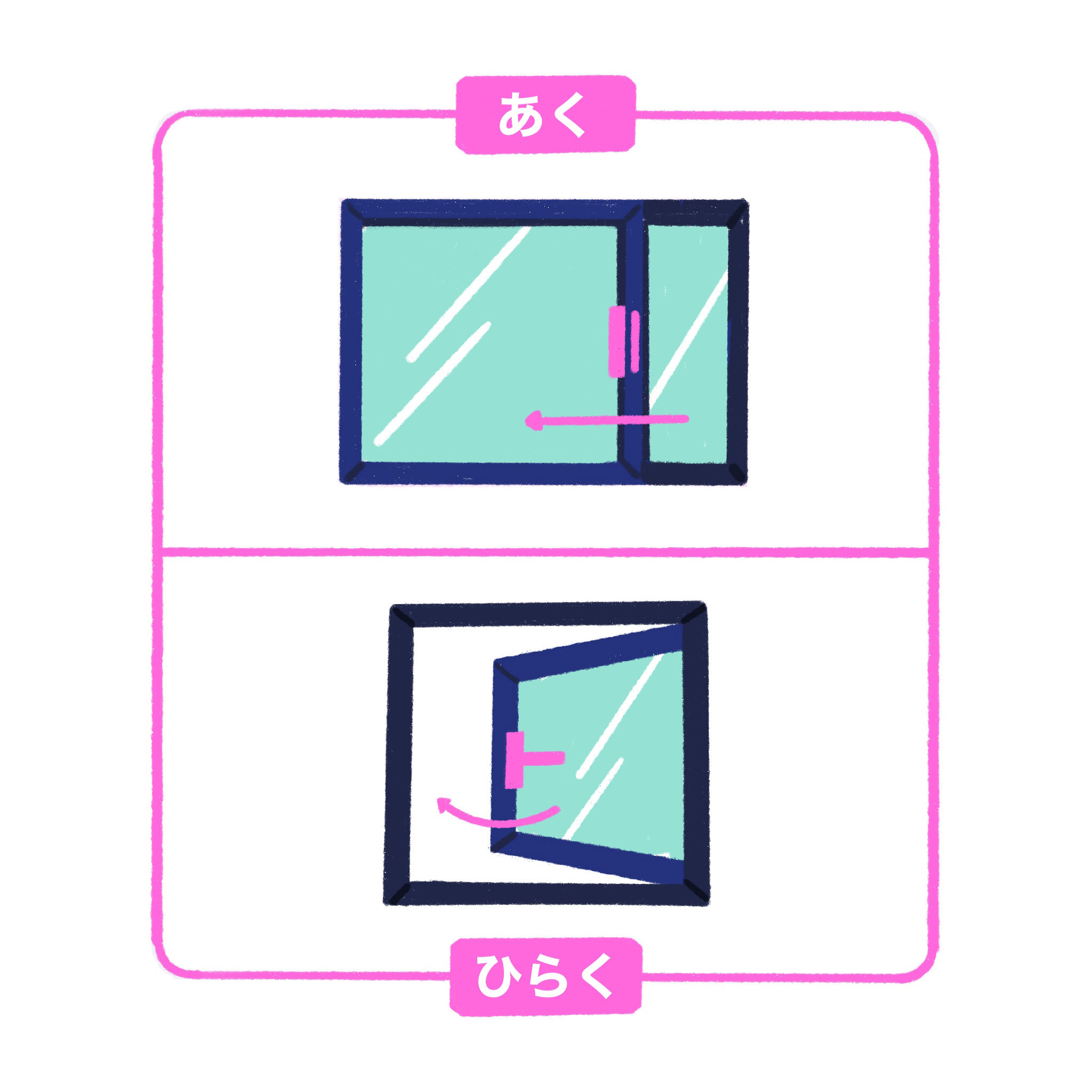

Next, let’s compare 開く with 開く when used as an intransitive verb. As you learned earlier, intransitive verbs describe a change in the subject (here, from being closed to open) without necessarily specifying the cause. For example, to describe the opening of a window, you can use these phrases and say:

- 窓が 開く。

窓が 開く。 - The window opens.

In this intransitive expression, somebody or something opened the window, but we don't necessarily know who or what. Maybe a ghost did it, or maybe it was just the wind. Whatever the case, all that matters is what happened with the window — it opened.

So the difference between our two intransitive verbs comes down to the difference between あ and ひら. The sentence with 開く, which begins with あ, places focus on how the window was moved to create an opening. On the other hand, 開く begins with ひら, and its focus is on the physical movement of the window. Thus, while 開く can be used for the opening of any type of window, 開く is more suitable for hinged windows that can be swung open.

For the same reason, you would use 開く to describe a flower opening, as in 花が 開く, or for a book opening, as in 本が 開く, because it depicts physical movement.

What about when you are talking about opening your mouth? Just like the envelope-opening example in the last section, the opening of a mouth can also take either 開く or 開く, depending on what you'd like to focus on. That is, if your focus is simply on a space being created, 開く fits the description. Thus, to talk about someone whose jaw has dropped open from being dumbfounded, 開く is used. This is because your focus is not on the movement of the mouth, but on the fact that it is wide open in suprise.

- あきれて口がポカンと 開いた。

- I was dumbfounded.

(Literally: My mouth dropped open in disgust.)

On the other hand, if your focus is on the actual movement of a mouth opening up, such as on the lips spreading apart, then 開く works. For this reason, if you are talking about someone who had kept a secret for a long time and finally opens up to tell you the truth, 開く is more suitable, as in:

- 男の重い口がついに 開いた。

- At last, the tight-lipped man began to talk.

(Literally: The man's heavy mouth finally opened.)

Here, 開く can express the movement of the tightly-shut lips opening up. If 開く is used, it feels like a more abrupt opening. It feels too direct and frank to depict the intense moment of the heavy lips of the mouth lifting to finally reveal the secret.

Lastly, let's take a look at one figurative usage, that of someone opening their heart. In this case, you may think 開く is suitable because the focus is on the person's heart becoming accessible to others. However, 開く is usually used for it, as in:

- やっと彼女の心が 開いた。

- Finally, her heart opened up.

This is because you are describing it as if a tightly closed shell has finally opened up. If you use 開く, it would sound like an actual physical space opened up inside the heart, which doesn't make much sense in this context.

However, if something sad happens and you feel empty and emotionally numb, you can use 開く to describe this state using 穴 (hole), like:

- 心に大きな穴が 開いた。

- There's a big hole in my heart.

(Literally: A big hole has opened in my heart.)

In this case, your focus is not on the movement of what's opening up but on the open space being made in your heart. This hole represents your feeling of emptiness. 5

開ける

Another use of 開ひらける is to describe a view unfolding before your eyes.

This final section is about the advanced word 開ける. Earlier, you learned it's commonly used figuratively and carries a more formal tone. We touched on one example of how it's used, which was 開ける as in "becoming civilized/modernized." Here, we'll check out a couple of other examples to get a better grip on it!

Another use of 開ける is to describe a view unfolding before your eyes. Imagine you are on a hike, walking up a trail surrounded by the woods. Halfway up, there is an opening where you can look over the foot of the mountain. When you get to the opening, a beautiful view becomes visible before you.

- 眼前に美しい景色が 開けた。

- A beautiful view opened up before me.

In this sentence, 開ける is perfect because it can describe the beautiful view suddenly unfolding and spreading out in front of you. It carries a formal tone, so it matches the literary feeling of the sentence as well. If you use 開く, it sounds odd as it's more closely linked to the literal movement of something opening up.

開ける is also used to describe finding a way to move forward in a situation. For example, let's say you start a new business, but for a while it struggles to take off. Yet, you keep working hard, and gradually your business plan begins to find its way. To describe your situation, you can use 開ける and say:

- ようやく道が 開けてきた。

- Finally, things are looking up for us.

(Literally: Finally, the road ahead has opened up for us.)

In this example, it's like you were lost in the wild, but then the right track suddenly began to present itself to you.

A New Door Opened?

Yay, you made it to the end! There are plenty of other examples in the wild, but now you should be able to figure out why one is chosen over another!

To sum it up, the "opens" beginning with あ ( 開ける and 開く) focus more on creating space or an opening, while the ones beginning with ひら ( 開ける and 開く) focus more on the movement of something opening up. And they can be broken up further into transitive and intransitive functions.

Knowing all that and having plenty of examples in your back pocket, you should be ready to open a new door and step on through to your next Japanese language adventure.

-

Some dialects may use 開ける differently. For example, Awa-ben (Awa dialect) in Tokushima prefecture uses 開ける as a transitive verb. And just like 開ける, it can be used to describe the physical opening movement, as in 窓を 開ける. ↩

-

When used to mean opening a door, the differences between 開く and 開く are so subtle that native speakers are not necessarily aware of them. Some may use these two interchangeably without any intention of adding effect. ↩

-

This あける can also be written with the kanji 空, as in 空ける. While both 開ける and 空ける are used to describe removing an obstacle to create an opening, 開ける's focus is on "making it accessible," and 空ける's focus is more on simply "making a vacant space." Thus, 空ける can also be used for other situations where the focus is on making something empty/vacant, such as グラスを 空ける (emptying a glass), 家を 空ける (to be away from home), or 予定を 空ける (freeing up one's schedule). ↩

-

There is another expression for opening an newspaper, which is 新聞を広げる. ↩

-

Just like footnote [3], if it's to emphasize the feeling of emptiness, the kanji 空 might be more suitable, as in 心に大きな穴が 空いた. ↩