Earlier in December, I was extremely lucky and had the chance to go to an early screening of Studio Ghibli’s The Wind Rises (Kaze Tachinu). By this time, I’m sure many of us are aware that this is Hayao Miyazaki’s last film, as he declared in his retirement interview, though he has since kinda sorta come out of retirement (again).

I’m well aware of the amount of story summaries, spoilers, and background informations out there about The Wind Rises, so I wanted to discuss something a bit more different.

A lot has occurred during the last few years in Japan, with the most notable and society-changing incident that took place obviously being the Tohoku earthquake and tsunamis that wrecked Japan in March of 2011. Two (now almost three) years later, Japan is still dealing with the aftermath of this natural disaster— not only is Japan still rebuilding from the devastations of the quake, but the nuclear meltdown in Fukushima continues to worry the livelihood of the Japanese people. In addition to the natural disaster, the Japanese government under Prime Minister Abe is striving to pull Japan back up economically. Of course, the Abe regime’s actions and efforts aren’t without criticisms, as it is frequently condemned among the Japanese public.

In short, Japan is going through some tough, stormy times.

Ghibli’s Kaze Tachinu might be a historical fiction based on a designer of the fighter plane Mitsubishi A6M Zero— but as I watched the film, I couldn’t help but compare the Japanese society of today to that of the one illustrated on screen in front of me. Perhaps it’s the tumultuous times that Japan faced in the last few years that overlaps with the turbulence of Japan before it launched into WWII, but the events and scenes within the film forced me to compare the current Japanese society with the one that Jiro Horikoshi (the main character) lived in during a pre-WWII era.

So I came across this question and wanted to discuss it a little further after watching Miyazaki’s final masterpiece—what did Miyazaki want to say about the Japanese society today through this film? Hopefully I’ll be able to give a different perspective of this film without giving away the plot!

To Be “Japanese”

One thing that’s particularly interesting about this film is that it’s based on an actual historical figure, Jiro Horikoshi, who designed the infamous Zero fighter planes.

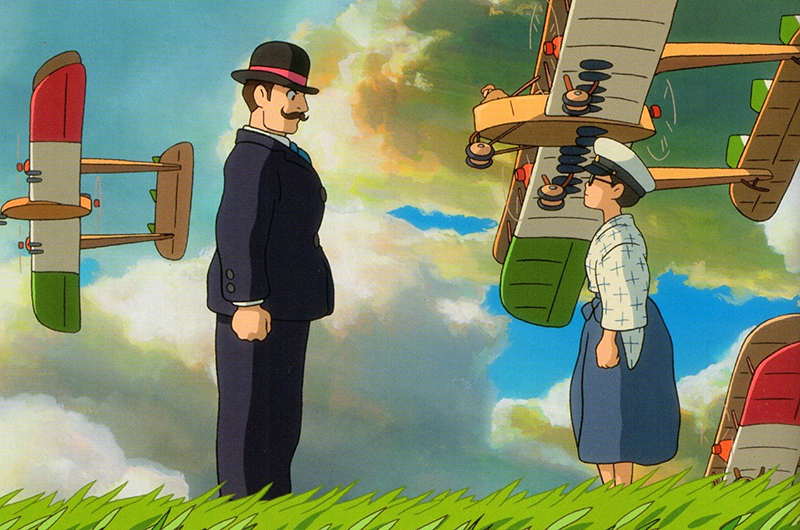

Throughout the film, Jiro meets people of different countries— the famed aircraft engineer and designer Caproni of Italy, the European engineers he meets during his travel to a German aircraft manufacturers, to name a few. I think this movie might be the first time Miyazaki illustrated interaction of characters of different nationalities so clearly to the audience— and perhaps intentionally to make the audience (in this case the Japanese ones) think of what it means to be Japanese.

Historically speaking, Japan appears to have always played the role of “catching up” to the West— for the longest time, Japan’s goal has been to modernize to join the ranks of US and the European states, and maybe even surpass them. Miyazaki’s film touches upon this notion in the film through Jiro’s interaction with the engineers of a leading German aircraft manufacturer.

But the highlight here isn’t that Japan lagged behind technologically in terms of aircraft manufacturing— it’s how Jiro interacts with his German counterparts. Jiro’s a collected individual, and seeing the way he interacts and negotiates to achieve an “equal playing field” with the German workers might have been Miyazaki’s desire to remind his Japanese audience to be proud of who they are. It’s not exactly imbuing them with nationalism persay, but perhaps Miyazaki wanted to remind his Japanese viewers that despite certain disadvantages to other states, their country holds a lot of good qualities as well, many of which are portrayed through Jiro’s personality and nature.

Slowing Down

There’s quite a lot of comparison between the “old” and the “new” in the film, during which Jiro was at the forefront of modernizing and making the “new” generation of Japanese airplanes. Jiro might have been placed in charge of designing a new, fast and durable fighter plane in the film— but throughout the film, he drops hints of his appreciation for slowness.

“Is “fast”, “modernity” and “convenience” the be-all and end-all?” I felt like Miyazaki was constantly throwing this question at me during the film. It’s an appropriate question for the Japanese society today, especially in the light of recent Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011. Sure, nuclear energy is convenient for a country like Japan that lacks energy resources— does it mean it should put its dependency and priority on it? This might just be one example, but I felt that Miyazaki was beckoning his audience to question this dependency on modernity, and instead consider the alternatives and remember how things were done in the past. There’s not only one way to do things— and perhaps Miyazaki wants his audience to recognize the implications of such conventional methods on the society today.

All You Need Is Love

My god, the PDA in this film.

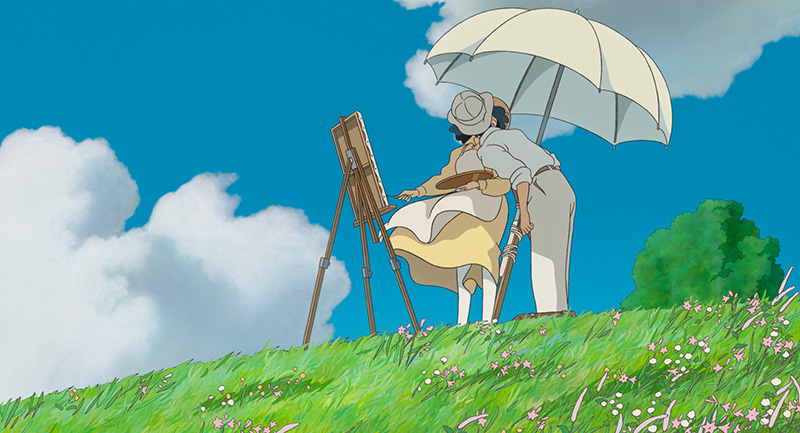

I’m sure many of you are aware that this movie, aside from being about the aspirations of a budding aircraft engineer, also has romance. In the film, Jiro meets and falls in love with a beautiful yet ill-fated girl Nahoko. Despite her illness, the two lovers seek to cherish each other, treasuring every moment that they get to share together.

Miyazaki films aren’t known for overt displays of affection— if I think back, the first time I recognized obvious kissing being part of the film was in Howl’s Moving Castle, when Sophie kisses Howl and in Ponyo on the Cliff By the Sea, when Ponyo also kissed (more like pecked) Sosuke at the end of the film.

Regardless, The Wind Rises goes past the light pecks and kisses and really goes above and beyond to show Jiro and Nahoko’s love for one another— and if the film insisted on such blatant forms of PDA all throughout the movie, I knew it meant something significant.

Despite the volatility in their era, Jiro and Nahoko stuck to one another and supported each other— Miyazaki might have wanted to relay the same lesson to the Japanese society today, which also faces equally disturbing political and socioeconomic issues. As a country still rebuilding from a massive earthquake, there’s a lot that needs to be taken care of in Japan— perhaps through his film, Miyazaki is urging the Japanese to support one another, to cherish your loved ones, and to have each other’s backs in this time of struggle. The Japanese society is still in for a wild-ride, and the people can’t possibly stand it without the help of others. As simple as it might sound, helping other people- and being helped by them- can’t be any more relevant to the Japanese society than today.

All you need is love— and everything will fall in place. I felt like that message sat well in me at the end of this beautiful movie.

So, when this film comes to a theater (or download) near you, be sure to watch out for some of these things.