"What's this?" I asked, unfolding the cloth my friend had handed me. It opened into a big rectangle.

"It's a present for you," he said.

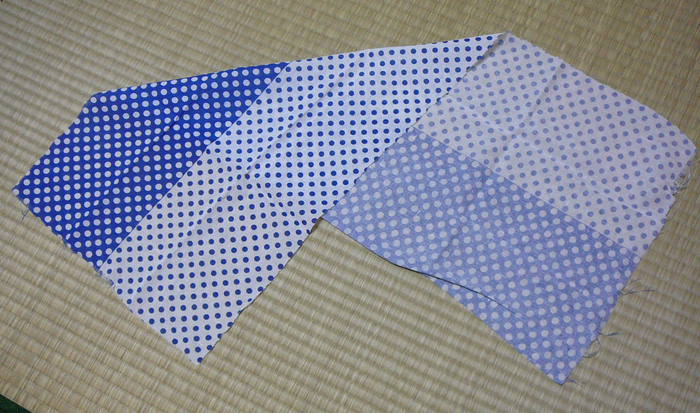

"Thanks, but what's it for?" Aside from its polka-dot pattern the cloth was rough, thin and unhemmed.

"A lot of things. You can wrap stuff in it," he explained.

"Wrap stuff in it?" I imagined a hobo carrying his worldly possessions in a cloth on a stick. The gift confused me, but I pretended to be grateful. Eventually my friend left and the cloth found a home in the closet. I had nothing to wrap anyway. And I didn't intend on wandering the earth – at least not yet.

To the closet with you!

My first experience with tenugui was awkward to say the least. A piece of frayed cloth made a strange gift. It didn't seem useful at all. I had no idea the simple cloth has such a rich history or wealth of uses.

- In Its Simplest Form

- The Origin of Tenugui

- Widespread Popularity

- Birth of Style

- Don't Call it a Comeback – Tengui in Modern Society

- A Lesson Learned

In Its Simplest Form

At first glance a tenugui doesn't look like much. It's fraying edges and thin constitution resemble a used rag – at least to this Westerner's eyes. I even felt that the elaborate images and patterns of some tenugui would be better served on canvases or posters than on vulnerable cloths.

And sometimes that's all tenugui are- plain cloths or rags. In fact, tenugui are sometimes used as rags for drying one's hands or cleaning. So it's no surprise that tenugui's kanji tenugui 手拭い is written with te 手 for hand and nuguう 拭う for wipe. But these "hand wipes" are the plainest, cheapest and least impressive of the tenugui family. Even tenugui's kanji fail to paint an accurate picture of the cloth's origin and capabilities.

The Origin of Tenugui

In reality tenugui have a distinguished pedigree. According to Kamawanu Shop's "A Rambling Talk About Tenugui", original tenugui date back to the Heian era, 794 to 1192 A.D. A time of peace and artistic exploration, The Metropolitan Museum of Art calls the Heian era Japan's cultural enlightenment. Developed alongside well-known cultural traditions like kana script, waka poetry, yamato-e painting style and narrative works like The Tale of Genji, it's easy to see how tenegui got lost in the crowd.

Heian era tenugui were an expensive commodity. Tenuguiya.jp describes them as finely woven cloths of silk or hemp used in ceremonies and religious rituals. Since techniques of mass production had yet to develop, fabric making remained a painstaking and costly process. As a result, prices remained beyond the means of common people.

Widespread Popularity

Tenugui would not become commonplace until well after the Heian period. Fabric making techniques improved throughout the Kamakura and Edo periods, driving cloth prices down while increasing the supply. Once tenugui became affordable, the cloth's versatility fueled its widespread use. More durable than paper, the cloth could be washed and reused. But most importantly, tenugui filled the needs of the time – becoming headwear, belts, wallets, and protective and decorative wrapping. With limitless uses, tenugui became a necessity.

Eventually tenugui became so cheap they could be used for cleaning both the household and its inhabitants. Tenuguiya.jp states that the spread of onsen and practice of routine bathing fueled tenugui's popularity, making it a bathhouse staple. With modern-day towels still years away, tenugui faced little competition.

But bathing wasn't the only cultural practice to embrace tenugui. The cloth's versatility made it a staple of summer festivals – worn as headwear, belts or used as a prop. Tenugui also served as headbands for kendo practitioners – soaking up sweat and protecting their heads from their bulky helmets. The cloth even became a tool of the underworld. The Japanese image of a thief wouldn't be complete without a tenugui tied off under his nose, a mask hiding his identity.

And where would a rakugo storyteller be without a tenugui? Performer Katsura Sunshine explains, "Rakugo features a lone storyteller… who, using only a fan and a hand towel for props, entertains the audience with a comic monologue followed by a traditional story." That towel, a tenugui, shape-shifts in the performer's skilled hands. With a little imagination it substitutes for any prop the act may call for.

Birth of Style

Usefulness wasn't the sole cause of tenugui's popularity. Competition between artisans and a growing demand for style fueled the cloth's aesthetic evolution. As tenugui evolved into a fashion accessory, better designs translated into higher profits for sellers.

But the competition wasn't solely economic. According to Kamawanu, design contests fueled artisans' fierce competition, giving birth to new dyeing and print techniques.

These techniques allowed artisans to do things they never could before. For the first time tenugui featured multiple colors, detailed patterns and beautiful images like landscapes, wildlife or people. The most beautiful designs became decorative pieces to display and admire.

However, designs weren't based on aesthetic alone. As tenugui trended, they trickled into the commercial scene and became promotional goods. Tenuguiya.jp explains that businesses, kabuki actors and sumo athletes sold or gave away tenugui adorning their names, images or logos. Families bought tenugui bearing their kamon 家紋 or family crests. Sometimes cloths bearing the owner's information even substituted for meishi 名刺 or business cards.

Advances in fabric production transformed tenugui from an expensive ceremonial tool to an everyday item enjoyed by the masses. And thanks to new dying and printing techniques the plain cloth evolved into a stylish fashion accessory and work of art.

Don't Call it a Comeback – Tengui in Modern Society

Eventually tenugui fell out public favor, replaced by handkerchiefs, cotton towels, single-use napkins and other modern fabrics. Cheap and disposable specialty goods like hats, purses, plastic bags, insulated cases, benou boxes and wrapping paper substituted for the old-fashioned cloth. Buttons, snaps, zippers and velcro revolutionized clothing and accessories, making tenugui seem simple and archaic.

But as Australian architect Harry Seidler said, "Good design doesn't date," and recent necessity has given tenugui new life. Perhaps in the rush to modernize, tenugui's better points were overlooked.

What sets tenugui apart from today's fabrics? Its thin fabric dries fast, so it's still ideal for cleaning, bathing or as a handkerchief or headband. Since they don't hold dust, tenugui are great for wiping surfaces like windows, counter tops, sinks, television screens and monitors.

Tenugui also have personality. Kamawanu explains that as a result of the dyeing process, particularly hand dying, no two tenugui are the same. Natural dyes may differ in color and strength leading to different results. Weather, temperature and humidity also affect the dying process.

Use affects tenugui as well. Gotokyo.com states, unlike other fabrics that degrade with use, tenugui actually improve. Repeated use softens the cloth making it more comfortable against the skin. As it ages a tenugui fades and creases, reflecting it's history and the character of it's purpose. As a result no tenugui are exactly the same.

Tenugui are popular with eco-crowds. Gotokyo.com describes tenugui as "a convenient and eco-friendly tool of life based in traditional Japanese culture." Since they are reusable and biodegradable, tenugui have little environmental impact. As such, tenugui are perfect for today's environmentally conscious societies – particularly in Japan, where the mottainai or waste-not philosophy has given reusable items extra prestige.

My favorite aspect of tenugui is one my friend also appreciated – they make great omiyage or souvenirs. Light, easy to transport and distinctly Japanese tenugui make the perfect gift from Japan. Local cloths commemorate famous imagery. For example, Nara's tenugui might feature deer. One I bought from Ehime has a mikan, or mandarin orange, tree. My blue Tokushima tenugui celebrates the area's indigo dyeing heritage. The Kyoto International Manga Museum even sells tenugui commemorating Japan's vintage manga series.

A true testament to tenugui's timelessness, the cloth is enjoying renewed popularity today.

A Lesson Learned

I recently contacted my friend and re-thanked him for his gift. He laughed when I revealed my original reaction, but seemed pleased with my newfound love for the Japanese cloth.

"Do you want to know why it's unhemmed?" he asked.

"There's a reason?" I said.

"It makes it easy to wring out and allows it to dry faster."

Even the lack of a hem, the characteristic that initially turned me off, has an advantage.

Speaking of my friend's gift, it's no longer stored away in a box in the closet. When I carry a bentou, I use the gift as a wrap. It helps get me through Japan's sweltering summers as a headband or hand-towel. And when I go to the onsen, I bring it along. I should probably invest in more tenugui.

But my favorite tenugui hang on my wall. I used to feel the beautiful images were wasted on a "rag," but isn't canvas just a rag too? A poster just a piece of paper? My collection reminds me of the places I've been or the festivities of the season. They also stand for the lesson I learned. Although it can be mistaken for a simple cloth, tenugui is one of Japan's most useful traditions and I plan on celebrating it whenever necessity calls. Gotokyo.com puts it best, "Tenugui have no rules – they're only limited by their user's imagination."