In February of 2013, the Tofugu staff made a four-day stop at the Showa Shinzan International Yukigassen tournament. We had to see it for ourselves, and this was our chance. This particular tournament (the Showa-Shinzan International Yukigassen Tournament) is the biggest in the world. Not to mention it's where Yukigassen was originally conceived.

With cameras, gloves, and warm jackets, we braved the mountain snows of Hokkaido. The result is this video, which will show you how Yukigassen is played. I'd recommend watching it, otherwise the rest of the article won't make a lot of sense. Plus, it's fun and educational!

As you can see, Yukigassen is essentially a combination of dodgeball and capture the flag, though it's not that simple. There is added precision and strategy that is normally associated with a professional level sport. We'll talk more about that later.

Getting To The Yukigassen Tournament

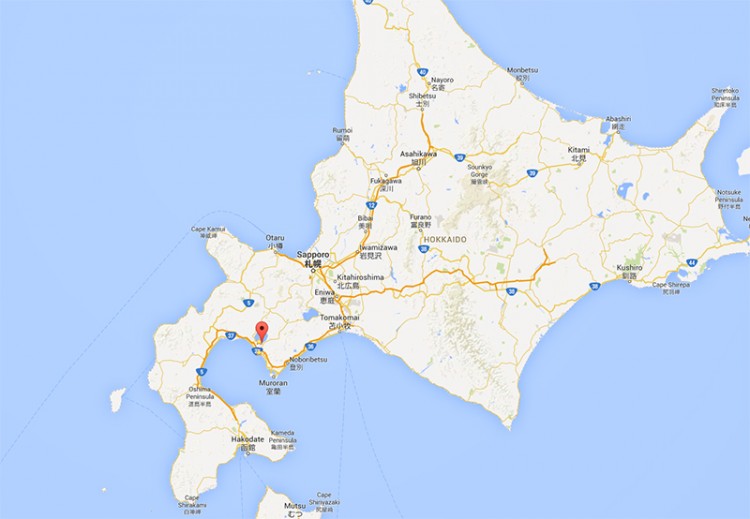

Showa-Shinzan is a small volcano where the yukigassen tournament is held. This volcano is near Soubetsu Town. If you want to visit Showa-Shinzan this is most likely where you'll stay. In the summer, Soubetsu Town attracts a lot of tourists thanks to its hot springs and "nature." During the winter there are still tourists visiting, though the numbers drop dramatically.

Thanks to that, Yukigassen was born. Town leaders were discussing ways to increase tourism in the cold winter months. They saw some people having a good time throwing snowballs at each other and apparently thought, "What if we make the snowballs way harder and had people throw them at each other at 90mph?" After some work and deliberation, the sport of Yukigassen came to be. Now Showa-Shinzan and the town of Soubetsu are flooded with tourists for about a week every winter.

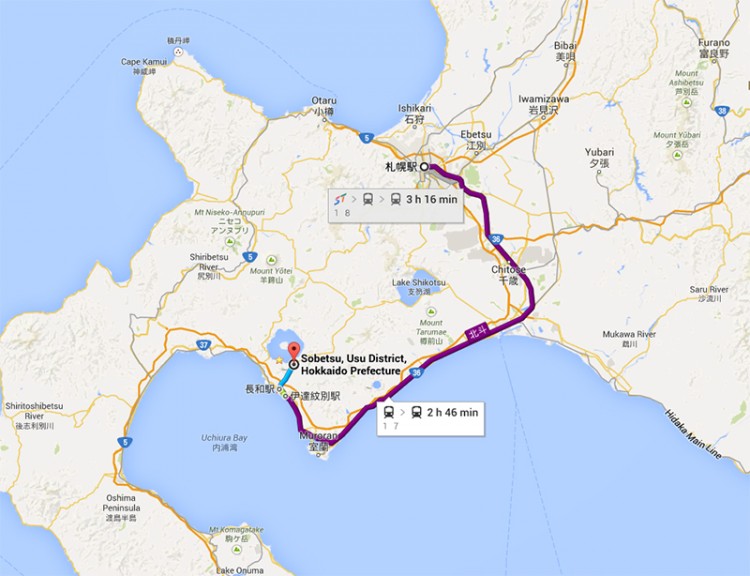

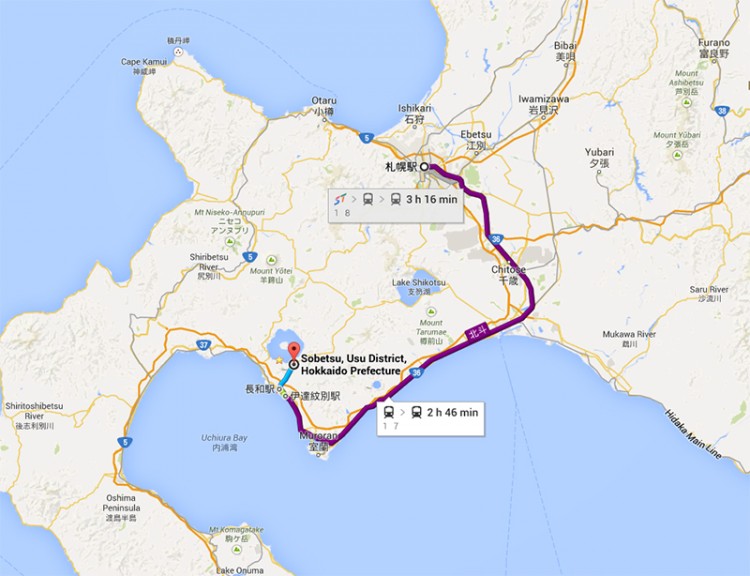

Despite being some kind of Mecca for Yukigassen players, it wasn't easy to get there. First we flew from Narita Airport to Sapporo in the late morning. That was the easy part. Then we got on a train that headed south to Hakodate. Although Soubetsu Town and Sapporo look pretty close on a map, trains make things fairly roundabout. There's a lot of mountains up in Hokkaido, after all.

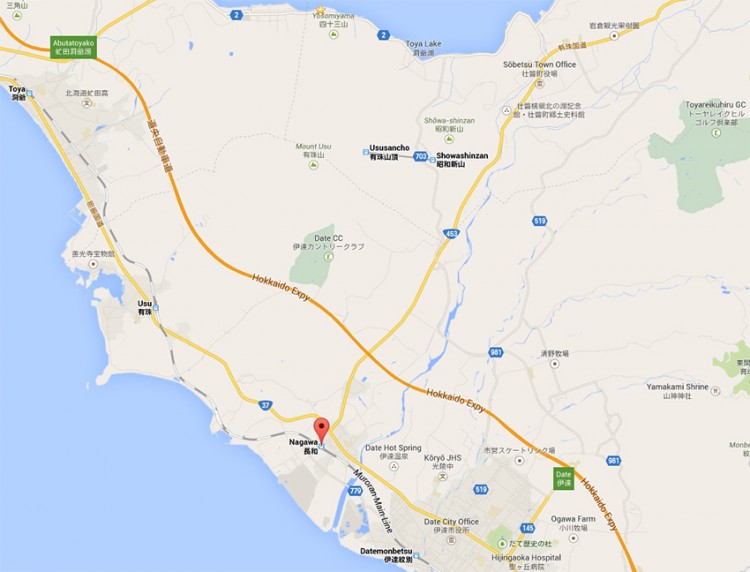

Blizzards, snow, and broken trains delayed us, so it wasn't the easy 3-hour ride that we hoped for. Also, if you follow the directions on Google maps, it has you getting off at Nagawa station. This is a big mistake. We were staying in Soubetsu town, and this is the closest station. But, there's nothing here. It didn't help that it was already dark when we arrived. I wrongfully assumed that there'd be a bus, or at the very least a taxi, waiting for us.

Of course, there wasn't any of this. But, there was a lone telephone booth (our phones weren't getting any signal). I called the hotel and the conversation went something like this:

Koichi: Hello?

Hotel: Hello! What can I do for you.

Koichi: Hi, we're staying there. We have reservations for tonight.

Hotel: Oh, thank you so much!

Koichi: Yeah, ok. Anyways, we got off at Nagawa Station and…

Hotel: Nagawa station…?

Koichi: Yeah, and I thought there was supposed to be a bus, or something… really anything here.

Hotel: There's no bus?

Koichi: No… is there a shuttle service or anything like that?

Hotel: Hmmm, no, sorry not to there. I think you got off at the wrong station. Is there a taxi, or something?

Koichi: Hmm, no. There's really nothing around here. Maybe we'll walk. But, we'll be late, so please keep our reservations.

Hotel: Okay! Is there anything else I can do?

Et cetera. Our only options were to wait for the next train (one hour or more, who knows with the snow conditions), or walk. We foolishly chose the latter. Apparently Toya Station is where we should have disembarked if we wanted to take the bus. If you're going you should double check this though, because we never tried it ourselves.

Soon after we began our trek we realized our mistake. Sure, it was only about three miles away but it wasn't an easy three miles. Snow was stacked up around us several feet high. The ground was either ice, snow, or a combination of the two. Throw in negative twenty degree (Fahrenheit) weather, our backpacks, and several switchbacks we'd have to climb and descend. After about a half a mile we came upon our savior… a Seico Mart, glowing orange in the distance! This wouldn't be the first time a Seico Mart (possibly) saved our lives in Hokkaido. We got in, bought some hot tea, and asked the employee there to call us a taxi. All was well in the world.

One harrowing 45-minute taxi ride and ~$100 later, we arrived safely at Toya Sun Palace (洞爺サンパレス), just in time to get in for our all-you-can-eat dinner. This was just about the only hotel left available, even though we booked a month or two in advance. I guess that goes to show how many people go to this tournament every year. The Toya Sun Palace is a little farther away from some of the other available accommodations, but it was probably one of the nicest / most touristy. It screamed, "We built this in the 80s during the economic bubble!" but after all the cold none of us cared about any of that. A little pampering would do us good. There was an arcade, a great onsen, a swimming pool / water slides, warm food, a lot of Chinese tourists, and even some Yukigassen teams. We talked to the Canadian team a few times, which was fun. They seemed like they were having a good time too, the few times we bumped into them.

We had arrived a couple days early from the start of the tournament to scope it out, so on this night we relaxed.

Soubetsu Town: Where Yukigassen Was Born

Staying in Soubetsu Town in the winter isn't the most exciting thing in the world. It's definitely more of a summer-tourism town, so it was quiet. The cab driver who took us to the hotel the night before gave us his card though, so we called him up and he did most of our driving for us on this trip. There are plenty of busses that go by Toya Sun Palace though, so it wouldn't be hard to utilize those if you didn't have access to a lavish no-limit Tofugu Travel Rewards Credit Card.

The town had some touristy shops, some restaurants, and most of the other things you'd find in a small town. We ate ramen, which was so-so, and we got some souvenirs from a gift shop. There wasn't much else to do after that, so we had the driver take us to Showa-Shinzan, where the tournament was to take place the following day.

The tournament grounds were still being set up while we walked around and took some video, though nobody seemed to mind. The most interesting monument was the volcano itself (Showa-Shinzan), which has a pretty interesting story. Apparently it didn't exist until the end of World War II, when it just sort of… appeared, as volcanoes sometimes do. It was kept a secret from the Japanese public, though, because volcanos appearing is supposedly a bad omen.

The volcano steamed and burped but everybody just went about their business. Just another day in the life of living near an active volcano, I guess.

Not much was happening on the day before the tournament, though, so we headed back to the hotel and went down the water slides forty or fifty times and then relaxed in the onsen.

Watching The Yukigassen Tournament

When we arrived on the day of the tournament, I'll admit that I had a not-so-secret wish that one of the teams would show up missing a player and somehow come up to me and say, "Hey, we need a strong looking dude to fill a spot and that's you!" I'd say "yes, if you insist" and have a great time, meet some lifelong friends, and take home a champion's jersey. I have great childhood memories that involve snowball fights, after all!

Then we saw the first match. That hope and dream went straight out the window.

Ouch.

First of all, it seemed like half of the players were baseball players. Probably pitchers. They threw hard and meant business. I think I saw a few knuckleballs even. And, with the cold in combination with the snowball compressing tools, the snowballs themselves were hard, too. I took one, stood on it, and tried to break it. There I was, a grown man standing on top of a snowball. It didn't break. These people may as well have been throwing perfectly formed rocks at each other.

The strategy involved was fascinating as well, and I'm probably only skimming the surface. You could tell a lot of time and practice went into their tactics. From how they rolled snowballs to the forwards to the captain / other team members telling a person behind a bunker which side they should dodge to as volleys came down around them. That way they could keep their eye on the opponents in front of them.

Notice the defender yelling tactics in the background.

The way they moved forward and gained advantage was well done too. Players didn't just throw snowballs indiscriminately (they do only have 90 snowballs a round, after all). They would wait, and sometimes the tension would grow and grow and grow… until one player made a mistake and all hell breaks loose. Attacks and volleys would be coordinated as well. A forward would have a much more difficult time avoiding arcing snowballs if there were three or four coming at him. You can't dodge in all directions at once, after all.

If you look carefully, you can see a volley about to hit this guy.

This guy is being careful and sneaky, not unlike a ninja (who were also known to enjoy a good snowball fight).

We weren't the only people to be impressed by all these tactics either. Talking to the non-Japanese teams, they seemed surprised as well. Many had never seen this level of competition. As one Canadian team member said: "It's like a chess match to them. They're so patient and methodical. We just try to run it and gun it, then take the flag. They just pick us off one by one."

Watching the Canadians, the Finnish, and the Norwegians play, you could see what they were talking about. The non-Japanese teams were a lot more aggressive… but they made more mistakes as well. Soon a few of their players would get picked off, and the Japanese teams would slowly and methodically move in for the kill.

Apparently the Canadians played a show-match with some local up-and-coming middle school yukigassen players the day before and had their butts handed to them. By kids! Hopefully that gives you some idea of the level that the Japanese teams play at. For many Japanese team members, it's a sport and not a hobby. Just as it should be.

To get a feel for this, I'd recommend watching some of these individual match videos that we put together. It definitely gets intense sometimes.

Although we had a great time watching, it's not something I'd easily recommend to everyone. It's not like going to a professional baseball game or something, where everyone's taken care of. You spend a lot of time standing around in sub-zero temperature. Luckily there are several vendors selling (very hot!) food and a couple tents with heaters, but for most of the day you're trying to avoid frostbite.

I'd guess that 99% of the people there were either players, friends/family of players, or people who worked for the Showa-Shinzan International Yukigassen Tournament. This sport has not reached a level where the masses go to watch the matches… at least not yet.

But despite that, there was quite the turnout. I was told that every year there are more teams and more people watching. Here's the opening ceremony, which shows you mostly players:

And, it's big enough to have its own mascot (though what in Japan isn't big enough to have its own mascot, ammiright?).

Most of the people here were either going to play Yukigassen or support an individual player in some way. I certainly didn't see any of the Chinese tourists from the hotel show up. I had the feeling that most people in Soubetsu Town didn't even know that the tournament was happening, though I only tried to talk to a few people about it.

That being said, it was one of my favorite memories of being in Hokkaido. It was cold and sometimes it was miserable, and the days felt really long, but it's something you can't really see anywhere else, at least not on this scale. Everyone was having a great time doing what they loved, and the energy was really great. No matter who won or who lost, everybody was excited for both the present and future of the sport. If we're lucky, maybe it'll become a winter olympic sport in the coming decades. If that happens I'll probably watch something besides curling for once.