Shōchū is a liquor with strong ties to Kyushu, especially Kagoshima. My appreciation of shōchū began in the year I spent studying in Fukuoka. I traveled all over Kyushu, but very little in Honshu. Late in my year there, I went to visit Kyoto and Nara for a weekend. It was there where I realized just how Kyushu shōchū is. Having traveled alone, I went in a bar near my hostel looking for a drink to sip while reading the manga I had purchased that day. I surprised the bar staff, by asking what shōchū they recommended. Friendly, but dumbfounded, one of them said “I don’t know. It’s not popular here. You really have been living in Kyushu haven’t you?”

Most Westerners have heard of sake, even if they have never tried it. Japanese beer brands like Asahi, Kirin, and Sapporo are also well known. However, relatively few Western people have ever tried shōchū or even know what it is. Even for those who have spent time in Japan, shōchū is often overlooked. Admittedly, it is an acquired taste for many, but that could be said of any liquor not disguised in a cocktail dress. Shōchū is a versatile drink, as I hope to show here. I encourage others to experiment and give it a chance, because I think there’s a shōchū out there for everyone. So sit back, relax, and have a cup, while I act as your guide through its history, making, types, and some of the myriad methods of enjoying this beautiful beverage.

History

It is thought that shōchū originated when distillation methods made their way to Japan via China, Southeast Asia, and Ryukyu to southern Kyushu. In fact, from its beginnings, Kyushu and more specifically Satsuma (modern day Kagoshima) was the area most strongly associated with shōchū. In 1410, the lord of Satsuma, Shimazu Motohisa, offered something called nanbanshu (“southern barbarian alcohol”) to the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimochi. It’s thought that this nanbanshu was something along the lines of a rice shōchū from Thailand.

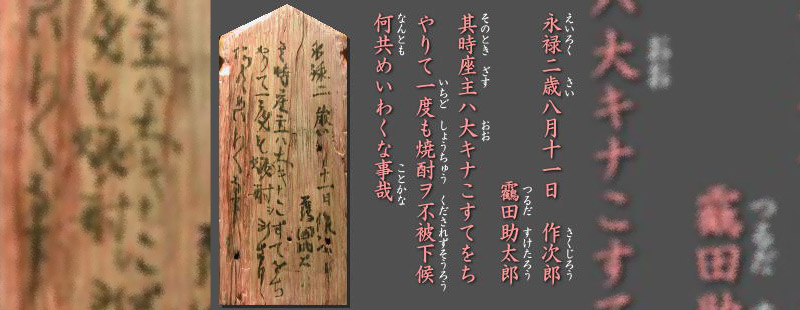

However, the earliest known appearance of the characters for shōchū was graffiti written by construction workers on a board in the roof of the Kōriyama Hachiman Shrine in Ōkuchi, Kagoshima. It dates from a 1559 renovation of the shrine, and in addition to its importance to the history of shōchū, it shows that people have been complaining about their bosses for a long time. It reads, “The high priest was so stingy he never once gave us shōchū to drink. How annoying!”

It seems that the first types of shōchū were based on rice or other grains. Around the beginning of the 17th century, the sweet potato was brought from China to Ryukyu. Europeans had brought it from its native South America to China not long before. It was introduced from there to Satsuma, where it quickly spread over the domain, and then to the rest of Japan. It was around that time that people began using the tasty taters to make shōchū, but rice-based shōchū remained far more popular until the Meiji period.

The man who deserves a lot of the credit for making sweet potato shōchū synonymous with Kagoshima was the daimyo of Satsuma, Shimazu Nariakira. By the time he took his office in 1851, a lot of the strict rules the Tokugawa shogunate had put in place had begun to break down and Western powers were encroaching upon Japan. Nariakira himself was open to all sorts of learning, including Western science, though he too feared for Japan’s future sovereignty.

He encouraged the modernization of military power, including the replacement of barrel loaded firearms with those which used ammunition detonated by percussion caps. The triggering explosive in those caps was mercury fulminate (“Breaking Bad” fans may recall that Walter White used this very same chemical to get himself out of a sticky situation).

One of its ingredients is ethanol, and for Nariakira the most ready source of ethanol was shōchū. To begin with, rice shōchū was used but, because the people relied on rice as their staple crop, Nariakira ordered research into using sweet potato shōchū instead. He thought that if sweet potato shōchū could become a special product of Satsuma it would be good, not only for military and industrial purposes, but profitable for his people as well. In his time, it wasn’t clear what results they would achieve, but during the Meiji period sweet potato shōchū successfully supplanted rice shōchū in Kagoshima.

Production

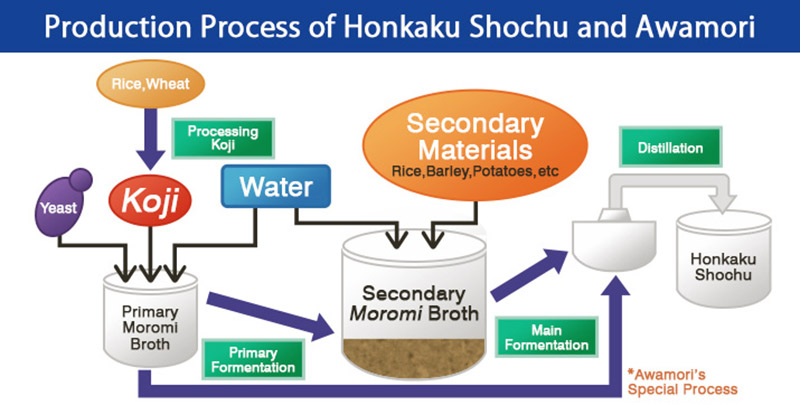

Now that you have some background, let’s look at how shōchū is actually made. As the chart below indicates, water, yeast, and mold called kōji (Aspergillius oryzae) are combined and left to ferment for a few days, creating a mash called moromi. There are different types of kōji, and they contribute different flavors. For Okinawan awamori, black kōji is used, but the rest of Japan generally uses white kōji.

When the moromi is ready, the rice and sweet potato (or whatever the main flavor contributor is to be) is crushed and mixed into the moromi. That secondary moromi is left to ferment for another week or so. Then it is moved to stills for distillation. Distillation increases the purity and alcohol level, but some shōchū has water added after the fact to achieve the desired alcohol content. If water isn’t added it’s called genshu.

Types

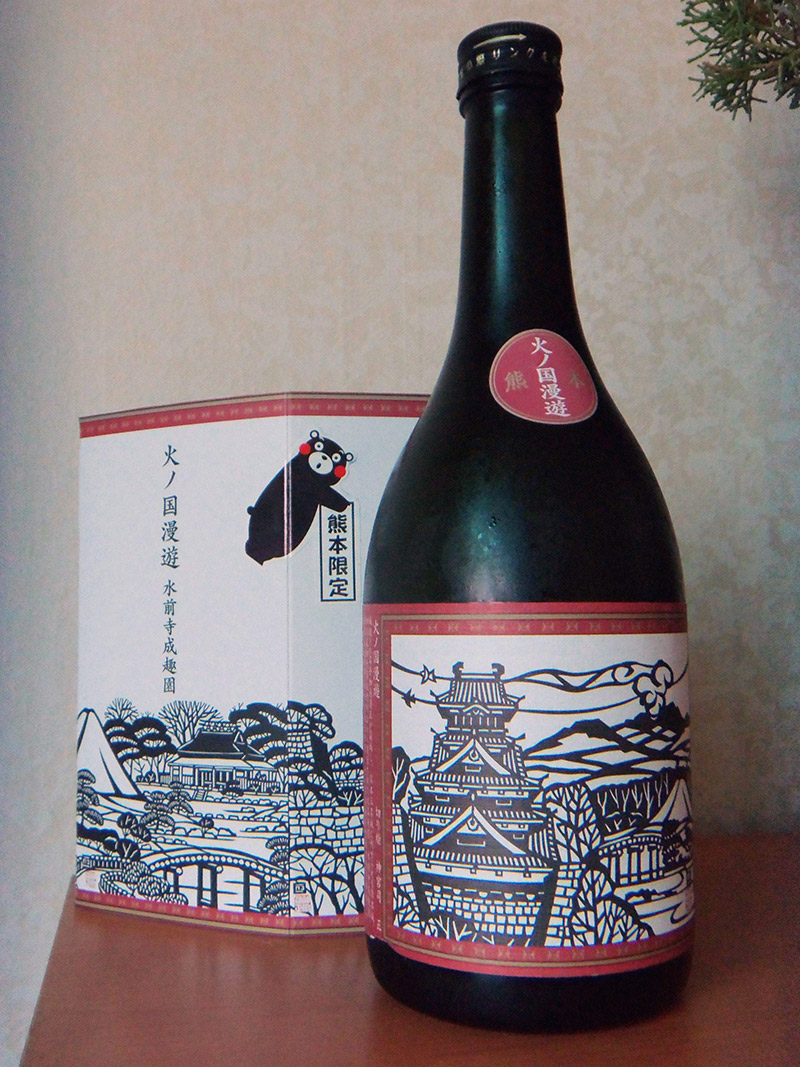

- Kome shōchū: Made from rice and being a bit milder in flavor makes it a good choice for beginners. There are some great examples from Kumamoto, including the hi no kuni manyū pictured at the beginning of the article.

- Imo shōchū: Made from sweet potatoes. Kagoshima is well known for this type. With its strong aroma and flavor, it may not be the best choice for a first timer, but it’s my personal favorite. It’s also the best candidate for drinking warm.

- Mugi shōchū: Made from barley. It tends to be fairly mild and is also a good beginner’s choice.

- Kokutō shōchū: Made from brown sugar. This type isn’t that common, but well worth a try if you can find it. It generally comes from the Amami Islands.

- Soba shōchū: Made from buckwheat. This type is only about forty years old. It’s the only one on this list that I’ve never tried myself, but it’s reported to be quite mild.

- Awamori: Made from long-grain Thai rice. This is Okinawa’s equivalent of shōchū. Although it’s generally 25-30% alcohol, it can be much stronger.

- Chūhai: A fruity, shōchū based cocktail. They can be hand mixed, or bought in a can for a very reasonable price (the canned ones don’t always use shōchū).

Ways to Drink

Not only are there many types of shōchū, but there are a number of ways to drink it as well. Give them all a try because each adds its own little something to the experience.

- Neat: The simplest method of consumption and it allows you to get a general idea of the shōchū’s flavor. However, for many shōchū is an acquired taste and some shōchū may be a little too harsh for beginners to enjoy straight.

- On the Rocks: A little ice is nice, especially in the summer. The downside is that some of the subtle flavors may not come out as much.

- Cut with Water (mizuwari): It may sound a little odd to intentionally water down one’s drink, but this is a common way to drink shōchū. The water rounds the edges a bit, so beginners might enjoy this way or on the rocks. A good ratio of water to shōchū is 4:6 or 5:5.

- With Warm Water (oyuwari): Drinking alcohol warm isn’t that common in the West, but it’s great for shōchū. If you’re doing this at home, the ideal water temperature should be about 158 F/70 C. You don’t want it too hot. Pour the water into your cup first, then the shōchū. The specific gravity of shōchū is heavier so it will sink and the two will naturally mix. The ideal ratio of hot water to shōchū is 4:6 for weaker shōchū or 5:5 for stuff that’s at least 25%. This method creates a nice aroma and brings out flavors you don’t get otherwise.

- Warm: A traditional way to drink shōchū, but not as widely available, particularly in more modern establishments. Shōchū in a little black pot (kuro joka) is heated either on a charcoal stove or in water. When vapor begins to come out of the pot’s spout it’s ready to drink. Don’t overheat it, and don’t heat in a microwave. Warm or cold, rice or sweet potato, in a cup or used to make ammo, shōchū has remained a versatile and fascinating drink for hundreds of years. I hope you’re inspired to give it a try. Until next time . . .Kanpai!