During my eight years in Japan, I've been to my share of conferences and they've covered all sorts of topics. Some are repeated every year – like "Successful Team Teaching" and "Fostering Student Communication." A few topics provided life-saving information like how to perform CPR, use an AED, and prepare for an earthquake. Others pointed out the obvious, like not destroying hotels rooms or driving under the influence.

One crucial topic remained curiously ignored, however: staying safe in Japan.

But Japan ranks as one of the world's safest countries! Home to an incredibly low crime rate! The chances of anything bad happening are slim to none, right? Why worry?

Ironically, Japan's reputation for safety gives the issue even more importance. Don't get me wrong, Japan is safe; safer than the countries most foreigners in Japan hail from. But that feeling of safety makes it easy to grow too comfortable, too complacent. And that's where danger lies.

Japan's crime rate may be low, but crime still exists. The special circumstances foreigners in Japan face as unique individuals in a homogenous society make the topic all the more important for visitors and ex-pats alike.

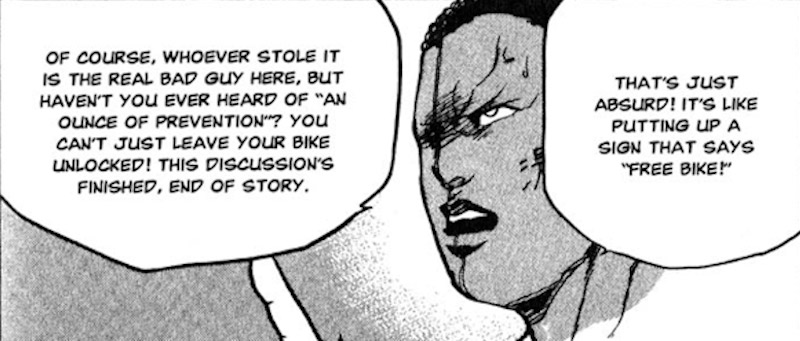

But fear not! An ounce of prevention can be all it takes to avoid becoming part of the small percentage of victims.

Japan's Safe Reputation

A 2014 Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development study ranked Japan as "the safest country in the world." The country touts "the second-lowest homicide rate after Iceland and the second-lowest assault rate after Canada."

So it's no surprise that people in Japan feel safe. Nationmaster.com, a site dedicated to statistical information of countries around the world, lists Japan as number one in people feeling safe walking alone at night. In overall worries about being attacked, Japanese citizens ranked third least worried. Living in Japan offers the undeniable luxury of safe feeling.

Rocketnews24 seconds that notion. In a poll ranking "the top ten instances people feel thankful to be Japanese," public order and safety ranked second behind Japanese food. One participant commented, "I can sleep on the train in peace, and even if I walk alone at night, it's not as dangerous as it is overseas." Interestingly, that comment was made by a 23-year-old female, a member of one of the most at-risk demographics.

The media, both in Japan and abroad, promote this safe, worry-free atmosphere. To people overseas, Japan's low crime rates seem like an amazing oddity. Children walk home and explore shopping malls with no adult supervision. Lone women stroll back allies and dark streets in both populated and unpopulated areas. People leave bags unattended while going to the bathroom.

I'm not alone in these observations. Lucy Rodgers of BBC News explained, "I had been informed that Japanese people did not lock their doors, left their cars running with the keys in the ignition and would never rip you off."

Japan's lack of crime and worry in everyday life shocks visitors used to caution as an everyday practice. Unaccompanied children riding the subway astounded Michael Weening in his article entitled "Is Tokyo Really Safe?" His blog continued the tale of how a man came to Mr. Weening's aid when he had lost his way in the mountains. His reply to the title question: "The answer is yes, (Tokyo) is that safe."

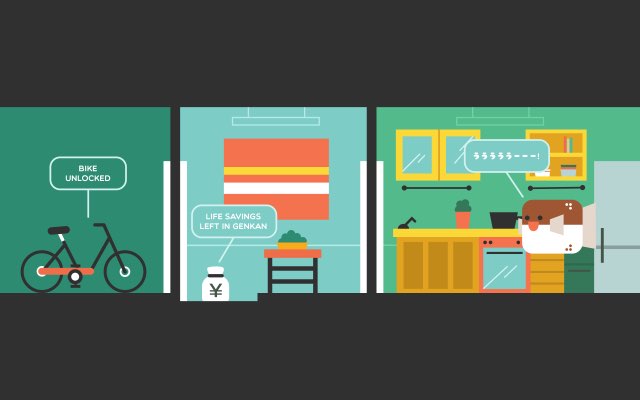

Anecdotes like that are common. An internet search brings up stories of lost wallets being found and returned with money intact, bicycles and even homes being unlocked with no negative consequence.

Japan's lack of crime makes headlines, impresses tourists, and provides a point of pride for the country and its citizenry. Japanese citizens worry about crime less than any other people in the world. The message is clear – Japan is safe.

But examples of safety are just that, examples. Remember, a low crime rate doesn't mean crime doesn't exist. That fact is key to avoiding victimization.

Foreigners' Special Circumstances

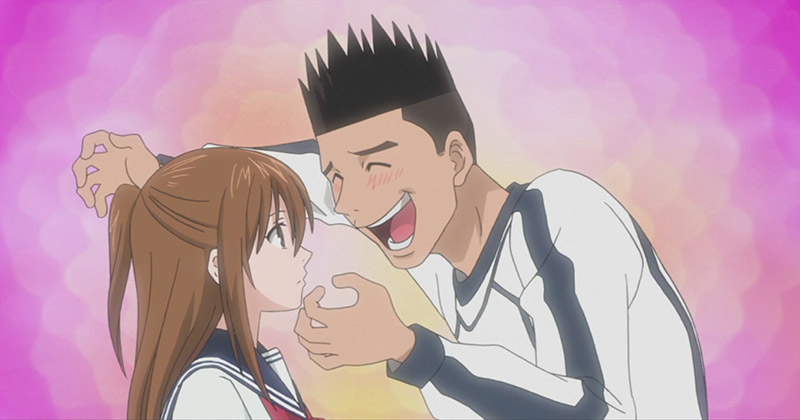

In a homogenous country like Japan, physical differences stand out. Size, hair-color, eye-color, skin color, and language all highlight the fact someone is not "Japanese." Foreigners stick out as exotic exceptions to the average Japanese build and appearance.

Considering the permeation and popularity of western culture and the English language, this can attract both wanted and unwanted attention. Lucy Rodgers explains,"There is a certain fascination – which may have something to do with how foreigners are portrayed on the TV – and you are probably the closest thing some people have to meeting such people, particularly in more rural areas." Any foreigner asked to take photos with random bystanders can attest to feeling like a pseudo-celebrity.

The less foreign people in a particular area, the more one stands out. This is particularly true for foreigners in small towns and secluded areas, where your name, address, and job become common knowledge. Random people might (think they) know your favorite foods, the onsen you frequent, your hobbies, or your love life.

Those with an interest in English may seek you out, hoping to practice. Some even go as far to make you feel it's your duty to provide such services – you know, being a foreigner in Japan and all.

Usually it's just fun, innocent gossip. Local foreigners provide an exotic flavor to everyday life and a chance to learn about life and culture beyond Japan. But occasionally those with an interest in foreigners, particularly of the opposite sex, aren't so innocent.

Holly Lanasolyluna of The Japan Times writes, "In a way, white women become plastic here: imports without feelings — strange, exotic dolls. And if we are dolls, perhaps the groping, leering, stalking and attacking is somehow justified in the perpetrator's mind as a game rather than a crime."

Despite the feeling of safety, people can feel reluctant to get involved, even when a crime is taking place. Holly Lanasolyluna reveals the details of an attack that occurred in Osaka. It was 10am when a stranger overpowered her and dragged her towards a love hotel.

Our struggle went on for at least 10 minutes, and none of the many onlookers helped or even appeared concerned. Finally, I saw a police officer down the street and screamed at my attacker, "Look! Look! It's the police!" That seemed to frighten him, and at that point he walked over to a nearby vending machine, bought me a water, said "gomen nasai" (sorry) and walked away.

Perhaps the language barrier is partially to blame. Even police officers fear dealing with communication difficulties. Attackers can feign ignorance if faced with charges. Add a culture of looking the other way to the mix and you have ingredients for disaster when the rare attack strikes.

"I now know I can't rely on the goodwill of strangers, as I have in the past when I was verbally harassed in countries such as Mexico," Lanasolyluna admits.

But just how rare are these kinds of attacks?

Women's Special Circumstances

Holly Lanasolyluna's police officer blamed her for the attack, "You're a young girl, and maybe you shouldn't be out by yourself alone at night."

"No details about the incident were recorded," she reveals, "Not only had every bystander ignored my pleas for help, but the police had also given me a terribly disappointing response – basically, 'Shō ga nai, ne?' (What can you do, eh?)."

Confused and ashamed, Lanasolyluna took the situation to the internet. The results were disturbing.

I posted a description of what had happened on Facebook and asked if people had had similar experiences. The response was overwhelming: stories of being attacked while jogging, being stalked by male and female students, being groped on the street in broad daylight, men masturbating on trains, attempted kidnappings. All of these stories came from strong women who put up a vicious fight but still walked away with psychological (and sometimes physical) injuries. In all of these stories, the victims had been in a "safe" public place but no one tried to help them or call the police. If this is so common, why does Japan maintain a reputation for being so safe? And is this image of safety actually facilitating these incidents?

She's not alone, Vivian Morelli of Japan Today writes:

Over my three years living all over Japan, I can recall numerous incidents involving a stalker, or a "chikan" (groper) on crowded trains or empty streets. Those Japanese men are usually curious or obsessed with foreign women, they're mentally unstable, and the experience is terrifying and unsettling."

The harsh reality is, women experience a greater rate of attacks no matter the location. In The Gift of Fear, Gavin de Becker explains, "Women… live with a constant wariness. Their lives are literally on the line in ways men just don't experience… At core, men are afraid women will laugh at them, while at core women are afraid men will kill them"(77).

Although these personal accounts don't represent the norm, it's important to take them into consideration. When it comes to one's safety, it's better to err on the side of caution.

Is Japan safe? Yes.

Is it one hundred percent safe? No.

Is it as safe as Japan would like us to believe? Apparently not.

The Horrible Truth

These accounts add suspicion to the growing evidence of police misappropriation of data in Japan. As a result, crime rates are higher than "official" reports would lead us to believe. By ignoring or failing to report crimes, particularly "unsolvable" crimes, Japan's law enforcement agencies keep crime rates low and success rates high.

In 2014 Asahi Shinbun broke news on police data manipulation in Osaka.

Osaka police have admitted they did not report more than 81,000 offenses over a period of several years in a desperate bid to clean up the region's woeful reputation for street crime. The revelation came earlier this week when embarrassed authorities said they had kept the data out of national crime statistics between 2008 and 2012… The vast majority of covered-up crimes were for theft… but hundreds of more serious offenses such as muggings and even murder may have been omitted from official crime data.

Havard Bergo of Nation Master Blog writes, "Former detectives claim that police (are) unwilling to investigate homicides unless there is a clear suspects and frequently labels unnatural deaths as suicides without performing autopsies."

Bruce Wallace of the Los Angeles Times blames a taboo in regards to handling the dead, but criticizes instances of falsified autopsies.

Forensic scientists say there are many reasons for the low rate, including inadequate budgets and a desperate shortage of pathologists outside the biggest urban areas. There is also a cultural resistance in Japan to handling the dead, with families often reluctant to insist upon a procedure that invades the body of a loved one… (But) police discourage autopsies that might reveal a higher homicide rate in their jurisdiction, and pressure doctors to attribute unnatural deaths to health reasons, usually heart failure, the group alleges.

Instances of falsified data force us to view crime rates with a shrewd eye and remind us not to grow too complacent. Perhaps Japan's crime rate statistics are too good to be true.

Too Comfortable

After the attacks, Holly Lanasolyluna reveals,

Interest from strangers that I could have dismissed as innocent curiosity a few years ago now gives me the chills… When I first moved to Japan, I tolerated the staring, following and persistent nampa (pickup artists), but after being assaulted twice in public, they have taken on darker undertones.

Lucy Rodgers admits growing too comfortable after her arrival in Kochi, a rural prefecture in Shikoku. But a highly publicized attack changed Rodgers attitude. The lesson learned is one that anyone visiting or living in Japan should take to heart. Rodgers explains, "The incident was an early warning to all of us that Japan may not be as safe as it first appeared."

When we constantly feel and are told we are safe, we start to believe it and drop our guards. We might leave a bicycle unlocked one day. Then a second. Then it becomes a habit until one day the bicycle disappears.

Lucy Rodgers puts it best, "There are always exceptions to the rule, and you need to remember that."

Strategies to Stay Safe

Despite Japan's ranking as the world's safest nation, crime happens. Women have the most to fear, but everyone can benefit from learning safety measures and taking extra precaution. The following strategies can get pretty heavy and might leave you feeling paranoid. My intent is not to instill a sense of fear but a sense of preparation, understanding, and even confidence. We are not helpless and being proactive can reduce the chances of falling victim in Japan, or anywhere.

Understand Who the Criminals Are

Since crime and violence involve perpetrators, it's important to realize who the potential criminals are. Few criminal lineups feature men in trench-coats with eye-patches, facial scars, and hook hands. How many times has the news reported, "He seemed like a normal, polite guy that liked to keep to himself"? As mild acquaintances often attest after the fact, criminals appear to be normal, even kind and friendly people.

Anyone can be a criminal.

In his book, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals that Protect us From Violence, violence prediction and management expert Gavin De Becker explains, "When we accept that violence is committed by people who look and act like people, we silence the voice of denial, the voice that whispers, 'this guy doesn't look like a killer.'"

Acknowledge Intuition

By gaining a greater understanding of criminals, criminal tactics, and human nature we can gain an edge against potential crime.

De Becker explains that nature has armed us with a very powerful safety tool – intuition. De Becker describes intuition as a useful, smart, intuitive impulse. He writes, "Intuition heeded is far more valuable than simple knowledge… Trust that what causes alarm probably should, because when it comes to danger, intuition… is always a response to something and always has your best interest at heart."

Intuition usually comes as a "gut feeling" based on subconscious environmental cues. But intuition differs from ordinary worry. De Becker explains, "Worry (is an) habituated, often projective and pointless activity that just makes us needlessly paranoid in situations where we don't have to be." Intuition, on the other hand, occurs out of the blue, often times without discernible reason.

If a situation doesn't feel right, it probably isn't, even if you can't figure out why at the time.

Pre-Incident Indicators and Criminal Strategies

But how should we react when facing confrontation? De Becker presents Pre-Incident Indicators – or PIN's – to help avoid falling victim to violence. The first step is accepting that anyone has the potential to commit crimes. The second is being aware of criminal strategies.

- Forced Teaming – When someone attempts to establish a connection, making us feel like we're facing a similar problem. Usually it's a simple statement to make us feel like "we're in the same boat." De Becker gives an example of a conversation between two strangers seated together on a plane that set off his alarm. The man commented to the woman, "I hate not having a ride." The woman responded, "Wait you don't have one either, shall we get a cab together?"

- Charm – Motivated niceness. "To charm is to compel, to control by allure or attraction" (De Becker). Charm is difficult to overcome because we want to trust kind, charming people. Remember that acting nice can be a strategy to make us feel safe and open up. No matter how charming or engaging someone appears, "you must never lose sight of the context: he is a stranger who approached you."

- Too Many Details – "When people tell the truth, they don't feel doubted, so they don't feel the need for additional support in the form of details." Liars and criminals say too much in an attempt to prove they're trustworthy. Be wary of strangers that offer too much information.

- Typecasting – A man labels a woman in a critical way (maybe even an insult), hoping she'll feel compelled to prove him wrong. Statements like, "You're probably too cool for a guy like me," are actually accusations used to create a sense of guilt. It's safer to live with the guilt than to prove yourself to a potentially dangerous stranger.

- Loan Sharking – A criminal wants to help you "because that would place you in his debt, and the fact you owe him something makes it hard to ask him to leave you alone." Beware of helpful strangers, particularly when they wear out their welcome.

- Unsolicited Promise – Criminals often try to strike deals to get closer to victims. "If you just talk to me for five minutes, I'll leave you alone, I promise." De Becker points out, "There's no compensation if the speaker fails to deliver." Be wary of coercive deals and promises.

- Discounting "No" – "No" is a word that must never be negotiated. "The person who chooses not to hear it is trying to control you…. With strangers… never, ever relent of the issue of 'no.' " Once you say "no," do not bend. It sets a dangerous precedent (that persistence will overcome) that you can be coerced.

By assigning labels to "approach strategies," De Becker makes them understandable, easy to discuss, and (best of all) memorable.

Ignore Empathy

Don't worry about angering or disappointing a stranger who approaches you. Anyone with good intentions will understand that receiving the cold shoulder from a stranger is a natural reaction. If the person does become upset or angry, all the more reason to avoid them.

Appear Strong

Never appear weak to a stranger or potential attacker. Stand straight, look them in the face, appear strong and able. De Becker explains, "It is better to turn completely, take in everything, and look squarely at someone who concerns you. This not only gives you information, but it communicates to him that you are not a tentative, frightened victim-in-waiting."

Treat Japan as Everywhere Else

Although Japan might feel safe, always maintain the same habits and caution you would in your home country. Vivian Morelli of Japan Today suggests, "It's fundamental to not put yourself in situations that could potentially be dangerous: walking alone at night in sketchy areas, taking dark roads/streets, not locking the door, or going inside the house of someone you barely know. NEVER, EVER do that."

Falling victim to crimes often follows committing actions, habits or feelings that defy logic. "He wouldn't do something like that," "She seemed so nice," or "It wouldn't happen here," are excuses on the road to ruin. Morelli continued, "People forget and think they feel safe, but they may not be and it can end tragically."

English teachers best heed extra caution. Take prudence when dealing with customers, students, and coworkers. Morelli explains, "If you give private English lessons, NEVER go to their house, only meet in a crowded cafe."

Tell Someone

If something worries you don't keep it secret. Tell your friends, trusted coworkers or the police. Keep important contacts at hand at all times. Don't worry about overreacting. It's better to feel silly afterwards than to become a victim.

Morelli writes:

Avoid any situation or place where he might try to approach you. Take the women-only car in the train at rush hour, even though lurkers sometimes find their way in. Most importantly, live in a safe neighborhood and building, know your neighbors, and always be aware of your surroundings.

Now That We're All Feeling Grim…

Of course not everyone is out to get you, although these strategies (and reading The Gift of Fear) might leave you with that impression. Since I started writing this piece, even I've been feeling a bit on edge.

The challenge lies in balance; being careful but not allowing worry rule your life. When dealing with new people, use extra caution. Until you've gotten to know someone well, limit activities to crowded places at reasonable times of day. Try not to allow feelings to overwhelm logical decision making. In the end, hopefully you'll separate the keepers from the riff-raff.

Remember, these tips and techniques apply anywhere, not just in Japan. We are not helpless. By taking extra precaution, acknowledging intuition while overcoming illogical feelings of obligation, empathy, and fears of overreacting we stand a better chance at avoiding victimhood.

Please Stay Safe and Enjoy Japan!

My arrival in Tokyo in the summer of 2007 coincided with one of Japan's most intense manhunts. Lindsay Hawker, an English teacher, had been murdered by one of her male students. The haunting wanted posters served as a reminder that even in a country as safe as Japan, we should always be cautious.

Yet, amidst all the media coverage and activity, the issue of safety was never brought up in work related meetings, lectures, or events. Hopefully it'll never be necessary, but The Gift of Fear inspired me to write this piece, thinking it might help someone, someday.

Japan is an amazing place with amazing people. Despite a higher crime rate than official data implies, it's still an astonishingly safe country. The Japan Times points out, "Even though the economy has been in the doldrums for two decades, the crime rate has not risen the way it often does in countries facing tough times." But even if Japan was as safe as statistics imply, it's still best to use caution.

Like CPR, AED, and earthquake lectures, I present this article hoping to offer useful, empowering information without any intent to fear-monger or victim-blame. And please remember, there is no fool-proof way to avoid crime, but learning a few strategies can help prevent the worst.

"I would have gone anywhere and done anything," Lucy Rodgers admits. "Especially where I was in rural Japan, but also in the big cities, everyone is so generous and friendly, you forget about safety issues. You don't have the radar for it (danger) anymore."

Please take caution, keep your danger radar turned on and protect yourself. Enjoy everything Japan has to offer, but never lose sight of possible dangers.