Everyone loves a parade. If you’ve spent time in Japan maybe you’ve been lucky enough to see a festival parade, but today I want to talk about a different sort of parade. During the Edo period, the Tokugawa Shogunate instituted a system of alternate attendance (sankin kotai), whereby the lords of Japan’s various domains were required to spend alternate years in their home domain and in the capital, Edo.

Sankin Kotai

This system of alternate attendance was designed as a way for the shogunate to control the various daimyo (lords). Spending half of one’s time in Edo made it harder to plot against the shogun. As further assurance, a lord’s wife and heir were required to remain in Edo.

There was also a more subtle, but very effective form of control at play in the alternate attendance system. Lords had to maintain a residence in Edo. Also, a lord had to travel back and forth from Edo every year, but he had to do so in a style befitting his station. This meant very lavish and expensive processions of hundreds of retainers and servants. Lords whose domains were far from Edo had to make stops along the way, paying for food and lodging for their retinue. All the expense incurred by these processions made it much more difficult for a daimyo to raise enough troops to threaten the shogunate.

The processions in general were quite interesting, but today we’re going to focus on one domain’s in particular. Satsuma domain, in southern Kyushu, basically corresponded to today’s Kagoshima Prefecture and their processions had something unique. In 1609, Satsuma conquered the Ryukyu Kingdom (today’s Okinawa Prefecture), a country with its own culture, language, and history. They left the Ryukyuan monarchy in place, but forced them to pay tribute to Satsuma. Sometimes, they also took part in Satsuma’s processions to Edo.

The Route

The processions to Edo (Edo nobori) fell into two categories: those to show respect for a new shogun (keiga-shi), and those sent upon the succession of a new Ryukyuan king (shaon-shi). There were seventeen such processions from 1644 to 1850. The round trip took roughly a year. They left Ryukyu for Satsuma where they joined with the Shimazu procession and continued to Osaka via the Sedo Inland Sea, then along the Yodogawa to Fushimi, where they proceeded on foot along the Tōkaidō to Edo.

The first three processions went all the way to Nikko to pay tribute to the shogunate’s deified founder, Tokugawa Ieyasu, but thereafter did so at a branch shrine in Edo. Having a foreign kingdom pay tribute to the shogunate in this way, not only in subservience, but at times almost like religious pilgrims, added to the Tokugawas’ image within Japan, if not abroad.

The processions may have enhanced the prestige of the shogunate, but they were of great political usage to the Shimazu clan as well. Satsuma was the only domain in Japan to rule over a foreign country, and the processions were an excellent way of reminding the shogunate and anyone else of this. On occasion the Shimazu were able to use their relationship with Ryukyu as leverage with the shogunate. In 1710 Shimazu Yoshitaka used it to convince the shogunate to promote his court rank. He argued that Ryukyu was second only to Korea in the Chinese tributary system, and as such he needed to be raised to a rank suitable for dealing with the Ryukyuan king.

Again, during the Tenpō era (1830-1844) the Shimazu daimyo was promoted after making the following argument: “as for maintaining control over Ryukyu, although it is indeed a small country, because it has diplomatic relationship with Qing, it places great value on matters such as court rank. . . . [Low court rank would] raise doubts and lead to numerous obstacles (samatage) in governing [Ryukyu].”

The Crowds

The Shimazu tried to enhance the prestige of the Ryukyuans by giving fancier titles to the king and procession envoys in 1712. In 1726 they began to have all Ryukyuans participating in the processions wear Chinese-style robes, whereas only the highest officials had done so before. The music played during processions was called rujigaku 路次楽, and was heavily influenced by classical Chinese music. This sort of exoticism only added to the attraction of the processions, which were observed along their route by many Japanese of all classes. The procession of 1832 attracted particularly large audiences :

The Ryukyuan tribute mission [ raichō 来朝]. . . arrived at the [Osaka] mansion and warehouses of Satsuma on the twentieth. . . . On both sides [of the river] great numbers of spectators, both male and female, flocked to see, and even floated boats out into the middle of the river [for a better view], clogging the channel. . . . On the twenty-fourth, when they went upriver by boat from the [Satsuma] mansion to Fushimi, it was just the same. It is said that the spectators were lined up along the river all the way to Fushimi. And what is more, at Fushimi and at Daigo, Imperial Princes, [members of] the Regent’s House, and the senior courtiers were pleased to appear [and watch]. It is even said that the Lord Sentō [the Retired Emperor Kōkaku] secretly made a royal progress [to watch].

It was no different as the procession made its way to Edo, where Matsuura Seizan, the daimyo of Hirado rented a house with a good view near the Satsuma mansion for the day to watch the sight, which he stated attracted numbers “surely neither greater nor fewer than for the regular Sannō and Kanda festivals,” the two largest regular public events in the city. Seizan recorded the experience as follows:

There was no one in any of the shops; they simply left their goods [untended]. . . . Along the route were male and female, young and old, both commoners and samurai. The lines of people were endless, and never gave out, all the way to Ueno. . . . The people were as blades of grass on a mountainside in spring; so many heads they were as grains of sand on a beach. . . . It was as if the dykes had burst and the water had begun to gush forth from the breach.

They were not the only ones watching. Also among the crowd was the popular author, Takizawa Bakin (1767-1848). Years earlier, in 1811 he wrote the novel Chinsetsu Yumiharizuki, the latter half of which was set in Ryukyu. It told the tale of Minamoto Tametomo, a warrior defeated in the Hōgen Disturbance (1156) who fled, eventually making his way to Ryukyu, where he married a princess, brought order to the fighting lords, and fathered Shunten, the first Ryukyuan king.

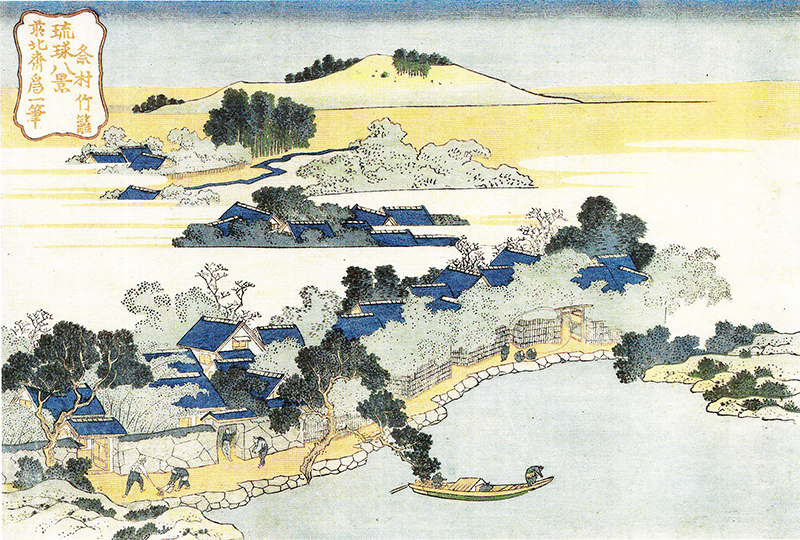

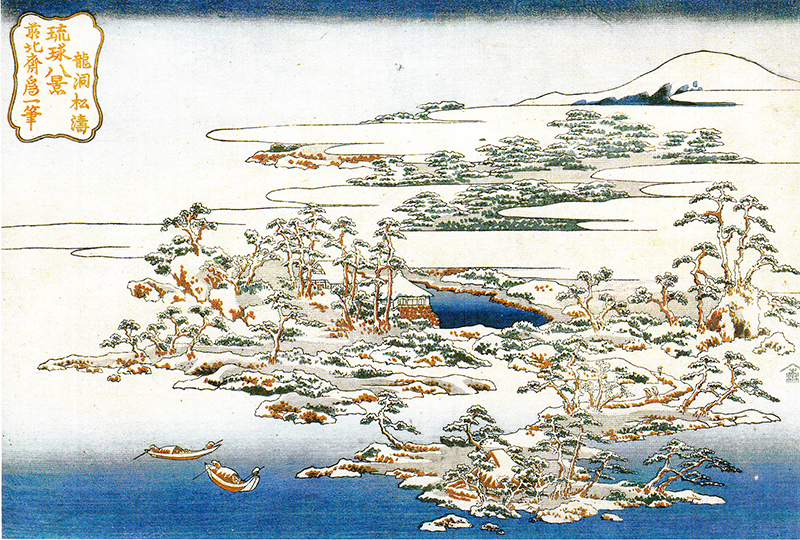

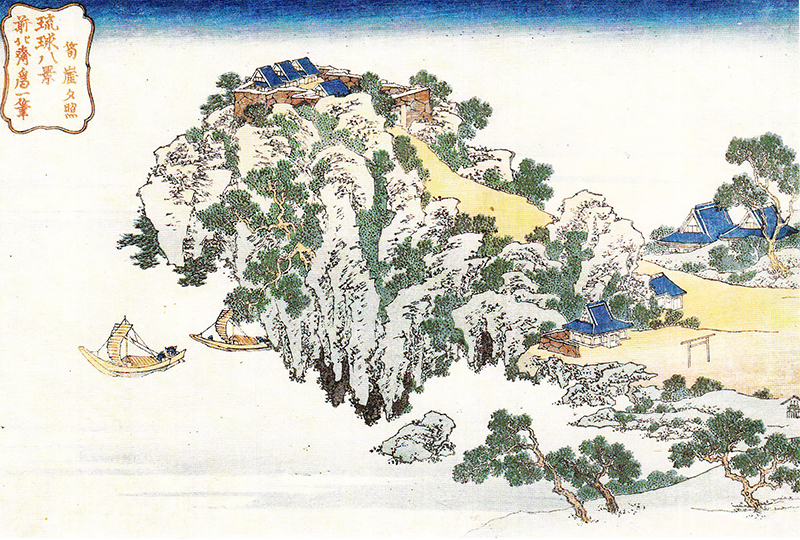

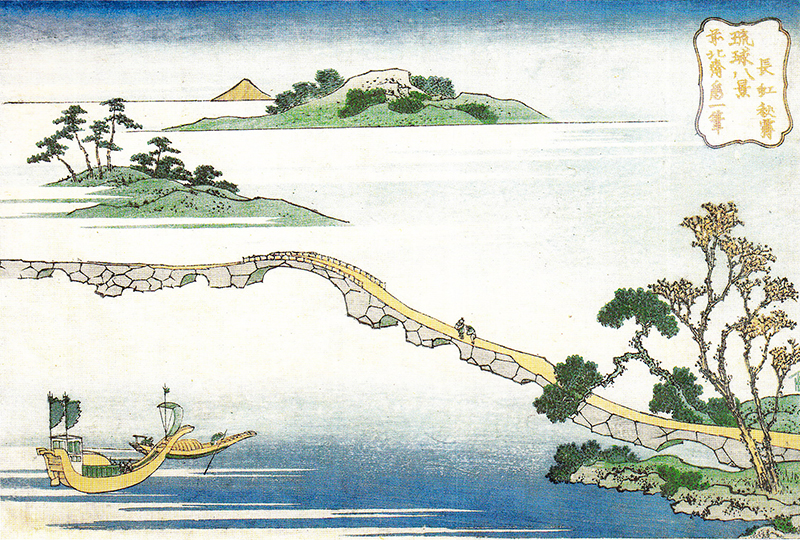

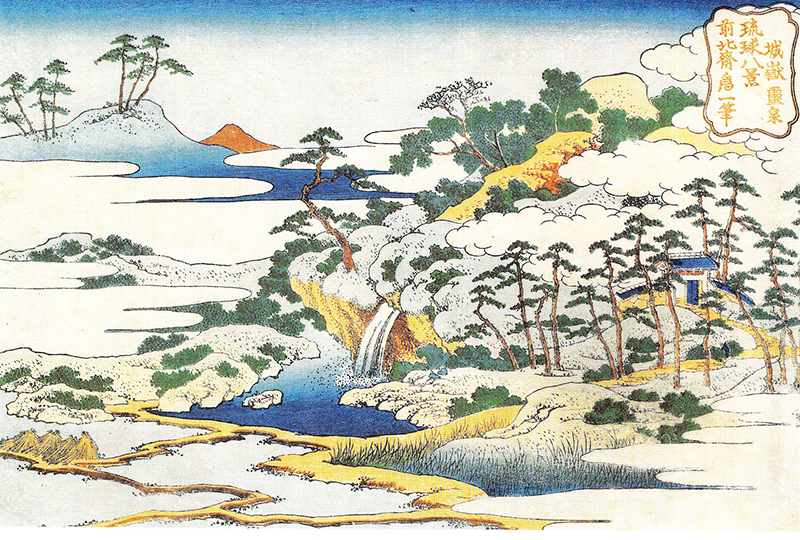

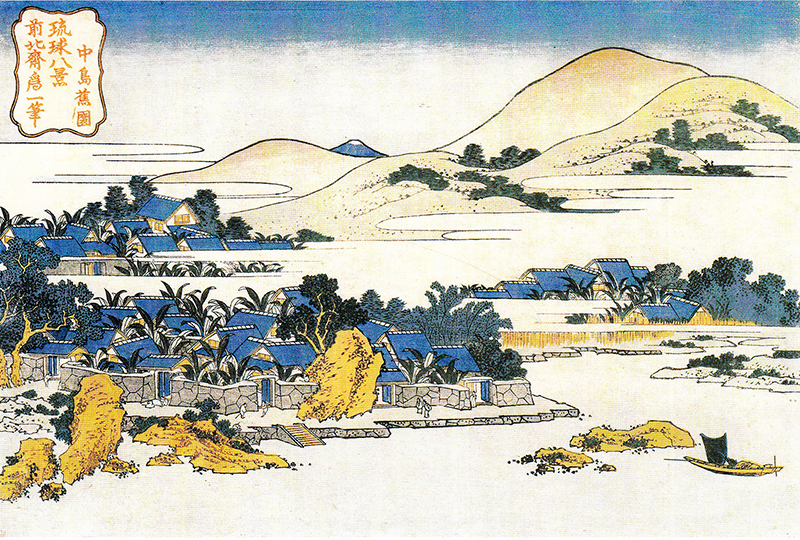

The book was illustrated by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), who also produced a short series of prints, “Eight Views of Ryukyu.” Bakin was not the first to present the theory of Tametomo as the progenitor of the Ryukyuan monarchy. The first known version of this story was written by a Japanese monk named Taichu shortly after Satsuma’s invasion in 1609. In 1650 it became a part of the Ryukyuan prime minister Shō Shōken’s history of the kingdom, Chūzan seikan. It may seem that Bakin and Hokusai were downplaying the differences between the Japanese and Ryukyuans, and there is an element of that. Still, Chinsetsu Yumiharizuki included many stories that may have been made intentionally strange. Neither man had ever been to Ryukyu, their only exposure to Ryukyu through the processions and books, so there was a strong element of the exotic.

In an era where very few Japanese people had ever been to Ryukyu, or seen a Ryukyuan person, it’s easy to see how the processions and the art inspired by them would have shaped their perceptions. They generally painted a picture of a people that may have some connection to Japan, but were still exotic and outsiders. These perceptions would echo through time, affecting modern relations between Okinawa and the rest of Japan.