When a country's birth rate shrinks, it can face major challenges. When a country's population gets older, that causes problems too. But what if both happen at the same time? Japan knows, because it's facing this exact crisis right now.

According to the Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA, a US think tank dedicated to research, analysis, and better public understanding of the US-Japan relationship, Japan is experiencing a "twin phenomena." Sasakawa USA has done extensive research on this (and many other issues facing modern Japan). So we turned to them for help in understanding Japan's population decline. They worked with us to create this article, providing a wealth of research and giving feedback during the writing process.

This may seem like a "Japan problem," but it will be affecting most developed nations in the next 30–50 years, including the United States. The world’s population growth is projected to be significantly slower1 and tilt strongly towards the oldest age groups. Japan is leading the struggle against a larger, worldwide demographics crisis. The island nation is also the United States' most important ally, helping promote peace in the region. So their successful navigation of this challenge matters. If we want them to remain a strong partner to the US and other countries around the world, we should care about their success.

In other words: If ever there was a time to pay attention to Japan, it's now.

- A Closer Look at Japan's Declining, Aging Population

- The Stats

- How Does a Declining and Aging Population Affect Japan?

- Fixing Problems Caused by Japanese Population Decline

- Are There Any Upsides?

A Closer Look at Japan's Declining, Aging Population

Japan's population is declining, but that doesn't mean the death rate is increasing. In fact, Japanese people are living longer, healthier lives than ever before. This is a good thing under normal circumstances, but pair it with a declining birth rate, and problems begin to emerge.

A healthy total fertility rate for replacement is 2.1 children per child-bearing woman.

To start, the total fertility rate (average number of babies a woman has over her lifetime) in Japan is currently 1.46. A healthy total fertility rate for replacement is 2.1 children per child-bearing woman in most countries. If your country is above 2.1, then you've got a growing population. If it's below this number, your population is shrinking.

The keyword here is replacement. These babies are meant to grow up, work, and replace people who retire. This is where long life expectancy (usually a good thing) becomes a problem.

What's Causing the Decline in Birth Rate?

Why is the birth rate in Japan declining? Several factors:

- Women are marrying later.

- Women have more options besides homemaking.

- Young professionals in Japan have been family-averse for the past 20 years.

- Unmarried women are less likely to have kids. Marriage is still the most socially acceptable way to have children.

For women in Japan, having kids means getting married and not working. Sure, it's technically possible for a woman in Japan to raise a child as a single professional, but Japanese society won't make it easy. So the decision usually comes down to career versus children. Women are choosing careers.

The Stats

This problem sounds bad, but it gets worse when you add the reality of cold, hard numbers (skip this section if you're easily scared by statistical analysis). Let's start with facts from the UN World Population Prospects in 2015. That will help us better understand the problems of Japan's population decline.

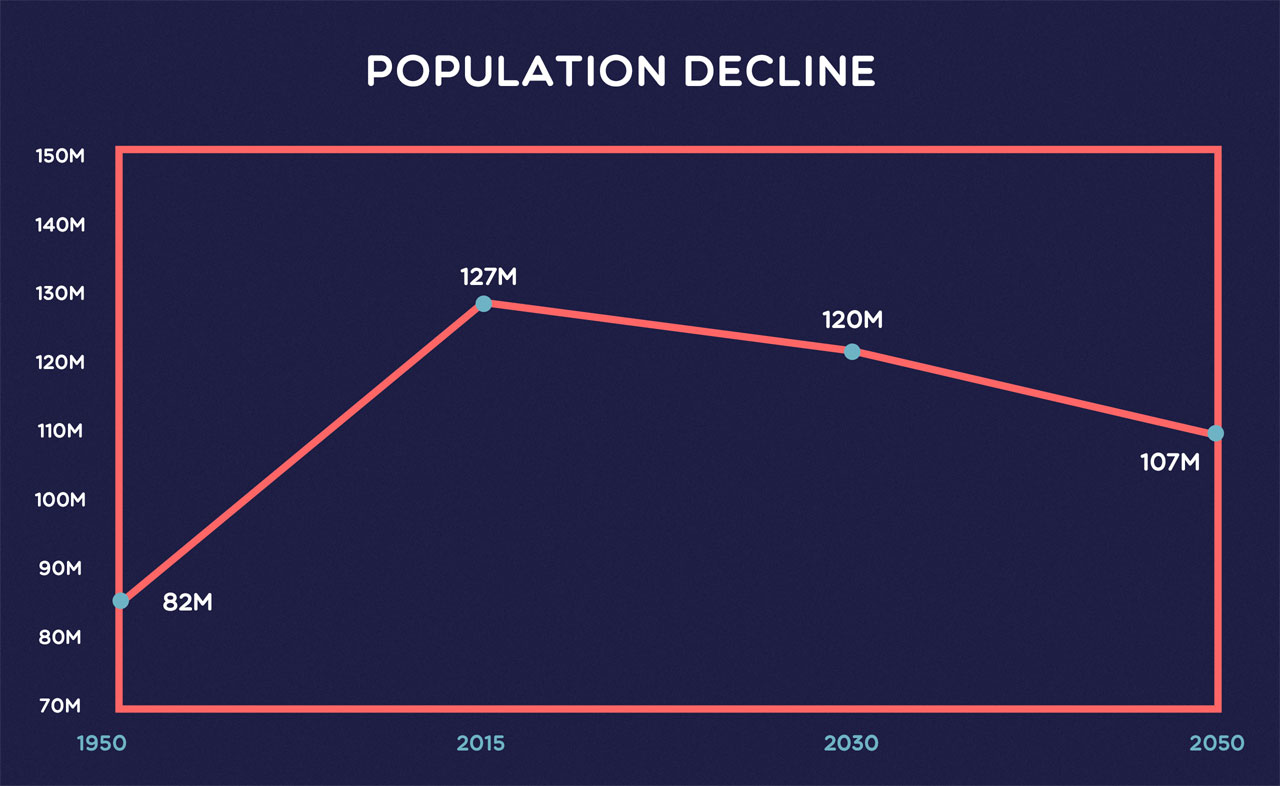

Population Forecast

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 82 million |

| 2015 | 127 million |

| 2030 | 120 million |

| 2050 | 107 million |

This statistic is self-explanatory. At the rate Japan is going, it's going to lose nearly 20 million people by 2050. That's a lot of lost labor.

Population Distribution

| Year | Over 60 years old | Over 80 years old |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 33.1% | 7.8% |

| 2050 | 42.5% | 15.1% |

42.5% of the population will be over the age of 60 by 2050. That leaves way fewer young people to do the work the country needs. Plus, the young people will be outnumbered and have to sustain the elderly.

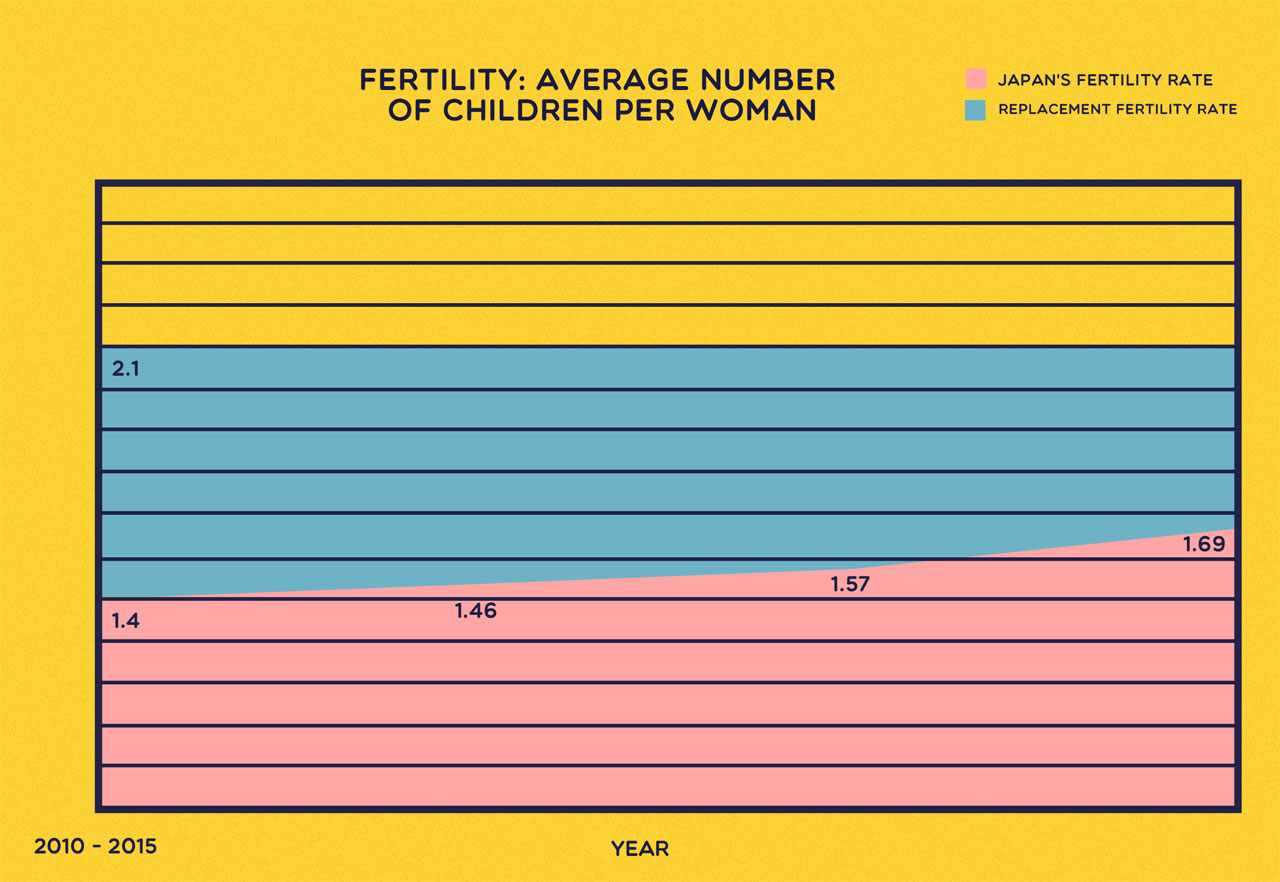

Fertility: Average Number of Children per Woman

| Year | Average Number of Children per Woman |

|---|---|

| 2010-2015 | 1.40 |

| 2015-2020 | 1.46 |

| 2025-2030 | 1.57 |

| 2045-2050 | 1.69 |

A replacement birth rate is 2.1, meaning there are two children born for every woman who can bear children. Japan has been below this replacement rate, and it's projected to stay that way.

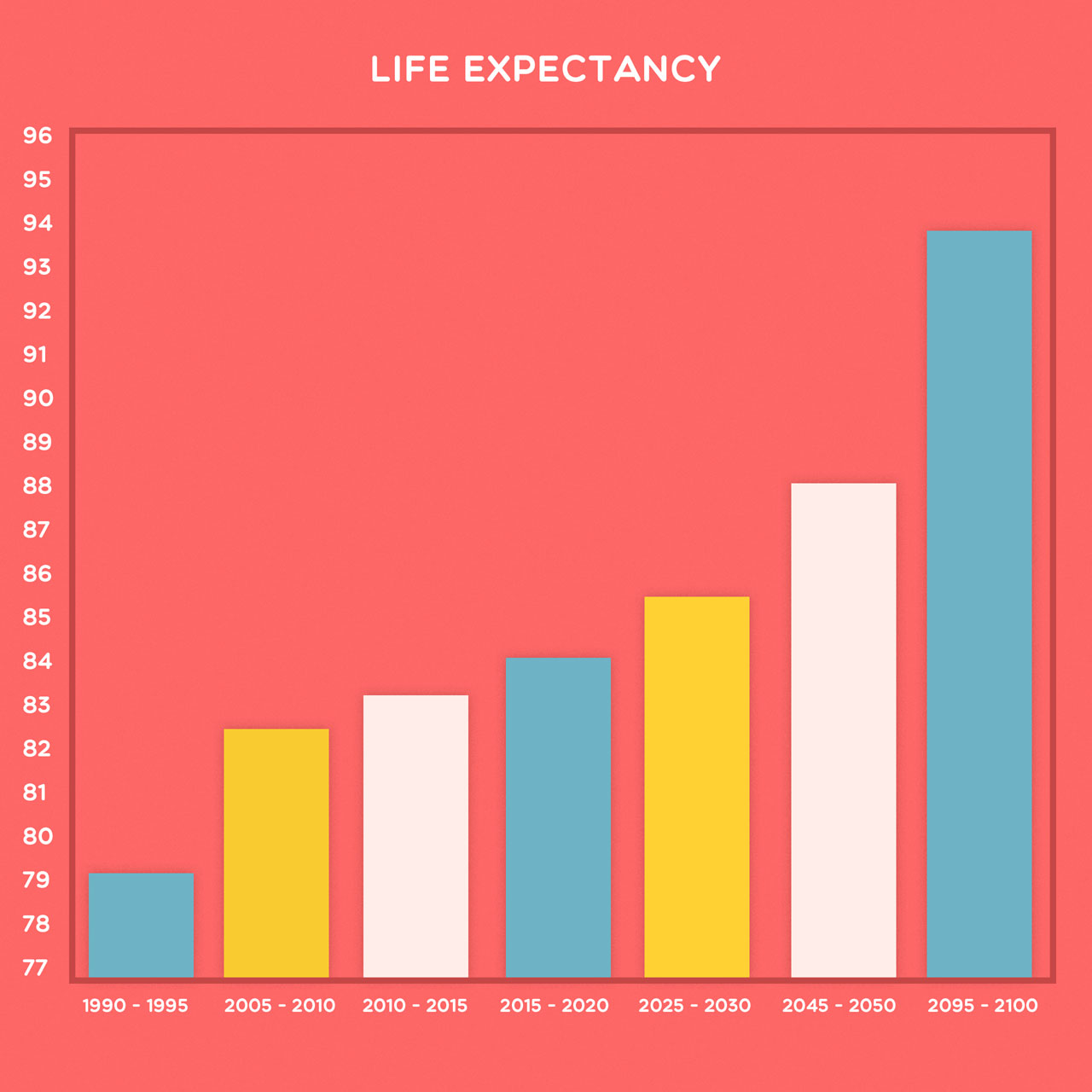

Life Expectancy

| Year | Life Expectancy at Birth |

|---|---|

| 1990-1995 | 79.4 |

| 2005-2010 | 82.6 |

| 2010-2015 | 83.3 |

| 2015-2020 | 84.1 |

| 2025-2030 | 85.5 |

| 2045-2050 | 88.1 |

| 2095-2100 | 93.7 |

Long life expectancy is not a bad thing. But more people living longer means more young people need to produce money and food for the elderly. Japan's life expectancy is projected to get higher not lower. So the low birth rate problem will be compounded.

Key Takeaways

Bottom line: Japan's demographic statistics don't look good. The country will lose 20 million people by 2050, which means it's losing a lot of labor. Unless the total fertility rate increases dramatically (projections say it won't), this trend will continue. On top of this, nearly half of the population will be over 60 by 2050. This means the shrunken workforce will also be half-retired, leaving more work for the labor that's left.

How Does a Declining and Aging Population Affect Japan?

Numbers are helpful with head knowledge, but understanding the effects of Japanese population decline really highlights the seriousness of the crisis. The ripples of the Japan's demographics challenge will impact the economy, politics, and Japanese society as a whole.

Economy

Deflation has plagued the Japanese economy for two decades, and attempts to reverse this trend have more or less failed. Unfortunately population decline promises more problems.

Lower population means fewer people spending money, and a greater pressure on Japan's GDP and wages. There's also falling land prices and exchange rate appreciation (I know "appreciation" sounds good, but it actually means a decrease in a currency's buying power). As Japan struggles, foreign investment may seem less favorable. And Japan can't afford to lose foreign investment in the face of this crisis.

Is there anything that can help reverse these effects? A full package of reforms that includes fiscal consolidation and aggressive monetary easing. But it's easier said than done.

Politics

As the population ages, the voting landscape drastically changes. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe might have trouble holding onto his position if conditions don't improve.

The side effects of the demographics crisis will hit the elderly especially hard, and they're likely to vote in response. Considering the expected growth of the elderly population, Abe had better tread lightly.

Another key demographic Abe is failing to attract: women. Japan is 23rd of the 35 OECD countries in female participation in the workforce. Abe is trying to remedy this situation with his "Womenomics" initiative, but we'll talk more about that later.

Society

The aging population is having the biggest impact on Japanese society. From changes in housing, to lack of funeral support, to the disappearance of entire towns and communities, the demographics challenge is reshaping Japan as we know it.

1. Unauthorized Nursing Homes

As Japan's elderly population rises, there's an increased need for care. A lack of nursing homes has led many retirees and their families to seek alternatives that are unauthorized or illegal.

In 2015, over 15,000 seniors were found in unauthorized nursing homes. Some of these facilities, though they fail to meet safety standards, are safe havens for low-income retirees with no place to go. But that's the best case scenario. Others are purposely predatory, seeking nursing insurance claims. In the worst cases, they are hotbeds for negligence and abuse.

2. Corpse Hotels

The increase in deaths has crematoriums putting people on waiting lists. Rather than keep the body at home or at the morgue, families store bodies of relatives in corpse hotels. These private rooms enable respectful storage of the bodies while loved ones wait for their turn to burn. In the meantime they can visit, place pictures and flowers, and mourn properly. Demand for this kind of business has been on the rise, and one particular hotel reported a 70–80 percent occupancy rate through 2015.

3. Solitary Death

Many elderly people live alone and have no one to take care of them. That's why there's been an increase in kodokushi 孤独死, or solitary deaths. The most recent data from 2013 shows 2,733 people over the age of 65 died alone in Tokyo.

This has created a need for services to handle the deceased's belongings. Though some operate respectfully, there are postmortem cleanup services that treat the possessions of the departed like trash or use false claims to add extra fees to the final bill.

4. Abandoned Homes, Disappearing Communities

With Japan's declining population comes a growing number of abandoned houses. By 2014, 8.2 million homes in Japan were empty. And 40% of them were not being offered for sale or rent.

Even bustling, lively Tokyo is seeing a rise in abandoned homes, a trend that's not likely to reverse any time soon. Communities desperate to attract home buyers have even started offering cash to outsiders willing to move into the community. The once bustling Yokosuka has set up an "unoccupied house bank" that highlights abandoned homes real estate agents won't show.

By 2014, 8.2 million homes in Japan were empty. And 40% of them were not being offered for sale or rent.

This trend affects local elections too. Young people are moving to big cities, so there aren't any new politicians to lead the dwindling communities. This prompted 43.4% of towns and villages to cancel their mayoral elections in 2015. Candidates in these communities were running unopposed.

Fixing Problems Caused by Japanese Population Decline

Japan's population is declining whether we like it or not, and we're just beginning to see the effects. Even though it's a slow process, Japan is doing as much as it can to change the situation.

Hopefully developed nations will take note of Japan's countermeasures, because these will be world issues in the near future.

Pro-Fertility Policies

With a shrinking population, the solution seems simple: more babies. But convincing a whole nation to have more kids is a difficult task. And Shinzo Abe gave that difficult task to Katsunobu Kato (a father of four). Kato is in a new cabinet position to "reverse the nation's sliding birth rate." His goal: raise the Total Fertility Rate to 1.8. How will he encourage people to have more kids? Maybe by encouraging men to help raise them.

A 2007 Cabinet Office opinion poll showed that women were more willing to have additional children (more babies!) if their husbands helped with child-rearing and housework. That's why the Abe administration wants to increase paternity leave to 13%. Dad helps with kids, Mom wants to have more kids, more kids happen, and that reverses Japanese population decline!

Unfortunately, only 1.72% of husbands took advantage of paternity leave in 2009, so giving more of something men don't use won't have much effect. Not unless societal changes take place along with it.

Women in the Workforce

Japan's shrinking workforce could expand – if only more women were included. With only 70.8% of women age 25–54 working, there is room for growth, and Abe has created a policy within Abenomics designed to encourage this. He calls it "Womenomics."

Womenomics is a series of structural reforms that, in theory, will make it easier for women in Japan to have careers. If successful, Womenomics could change the face of Japanese society by creating more flexible working environments and increasing Japan's GDP by 15% without any change to the population. This could delay the negative effects of the aging population for up to 20 years.

But for Womenomics to work, it has to overcome some obstacles. Here are four big ones standing in the way:

1. Tax Incentives

Currently, there are tax benefits for working men who have stay-at-home wives. This leads to women keeping their income below the designated level so their family gets the tax break. It's an incentive for women to stay out of the workforce.

2. Maternity Harassment

There are also institutionalized obstacles that policies and arrows can't touch, things like マタハラ short for "maternity harassment" where women are "encouraged" to quit their jobs once they become pregnant. Policies can help more women get jobs, but can't dictate how they will be treated.

3. Wage Disparity

In an article for the Wall Street Journal, Abe addressed differences in pay between men and women, admitting Japanese women earn 30.2% less than men. It's hard to get women to work if they know going in they'll be earning less for no good reason.

4. Lack of Daycare Services

Womenomics could increase Japan's GDP by 15% delaying effects of the aging population for up to 20 years.

Young women in Japan face an either-or choice: babies or career. Childcare in Japan is rarely outsourced to non-family members, which makes it difficult for women to have both a career and kids. Existing daycare centers have long waitlists. To meet the demand, Prime Minister Abe has pledged to expand subsidized daycare services to accommodate 400,000 children by 2018.

Local governments are doing their best to reach this goal, but right now they're not keeping up with demand. In 2015, the number of children on daycare waiting lists rose to 23,000.

Filling Vacancies in Labor Markets

Even if Womenomics is a success, Japan will still need more workers. There simply aren't enough Japanese citizens to fill vacancies in all the right labor markets. That leaves the country with two primary options: immigration or robots.

Immigration

With a native population of 98.5%, Japan has traditionally been averse to immigration as a cure for its ailing economy. Even the recent tourism boom has raised eyebrows among Japanese traditionalists who feel tourists are a disruption to the Japanese way of life.

Nevertheless, Japan is reconsidering its steadfast policy of keeping foreigners out of the country. Proposals to open the borders are being introduced, carefully crafted to avoid the red-flag word, "immigration." Instead, terms like "guest worker" are used to describe plans to increase the number of foreigners to Japan.

Masahiko Shibayama, an adviser to Prime Minister Abe, is proposing a five-year visa program that would allow foreigners to fill positions in unskilled labor markets. Abe has also promised highly-skilled foreign workers a fast track to permanent residency, as part of an effort to encourage top talent to choose Japan over other countries that are offering attractive incentives to professionals looking for new opportunities.

In addition, top economists are calling for increased immigration. Respondents from a poll in the Asahi newspaper agreed with the sentiment, hoping it will help offset the negative effects of Japan's population decline.

Robots

Japan is also considering a technology-based solution to the shrinking workforce: robots. The shortage of workers in nursing homes is especially dire, and several robotics manufacturers are developing machines designed to care for elderly residents (more on this below).

Robots in the prototype stage are being tested in banks, hotels, and stores. For example, a humanoid robot named Nao can answer questions in 19 languages at Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, and could come in handy during the 2020 Tokyo Olympics when foreign visitors require banking services.

Lawson convenience stores teamed up with Panasonic to create a fully automated cashier that scans and bags items without any human assistance. The automated system, called Reji Robo, was created specifically to fill the need of staff shortages.

Prime Minister Abe is also promoting a "robotics revolution" in the form of a five-year program to increase the number of robots in manufacturing, construction, and other industries. He wants the robotics market to grow fourfold by 2020, from 660 billion yen to 2.4 trillion yen.

Enhancing Elderly Care

More people are retiring, which creates greater need for help. That's why the Japanese government created long-term care insurance (LTCI) in 2000. Japanese people pay into the system at age 40, and receive benefits at 65. There is a series of interviews and committees that decide what type of care is needed for each individual, after which time, the patient gets to choose between a variety of care providers. These providers offer different things, from home visits, to grocery delivery, to stays in the hospital. Because the system encourages independence via a-la-carte services, it saves money that full-on "put everybody in a home" care would cost. This savings is then passed on to low-income patients who need extra assistance.

Caregiving Robots to Help out Senior Citizens

Unless elderly Japanese people become more comfortable with foreign caregivers (right now they're not), another solution will have to be found…or created! That's right, it's robots again. Here are a few caregiving automatons that have leapt to the forefront:

-

Twendy One: This robot was an early candidate from Waseda University. Twendy is able to gently handle drinking straws or hoist hefty senior citizens out of bed. Unfortunately, most news about this robot is over ten years old. Though Twendy's official website is updated once a year, it seems its heyday is past.

-

Robear: The Riken-SRK Collaboration Center for Human-Interactive Robot Research developed a 309 lb robot bear which can lift patients from bed to wheelchair. Human caregivers have to do this an average of 40 times a day, so removing this strain enables them to work longer and avoid injury.

-

Paro: Think of this plushy seal as a robotic therapy pet. Paro was created to calm dementia patients, but is now used in care facilities all over the world. It has microphones, tactile sensors, and motors that make it respond to human interaction. Physical help is important, but there's also a need for companionship and comfort.

These robots certainly help Japan's elderly care situation, but there are significant barriers to their success. For example, a robot can't know when it's injuring a human (that's why Robear has a big, red panic button on its back). They're also prohibitively expensive. The sensors in Twendy One's hands cost $21,500. Just the sensors.

Even if these barriers are removed, robots are still only supplements. The goal of robots completely replacing human caregivers assumes there will be major improvements in AI, mobility, and sensor systems.

Are There Any Upsides?

Every challenge presents opportunities, and the Japanese population decline crisis offers big ones. The smaller population gives Japan breathing room to address issues more important than GDP. Some of this focus is already aimed at closing the gender gap and inviting women into the workforce. There's also been much-needed reform of Japanese work culture.

Also it should be noted that, usually, a trend of fewer babies correlates to women becoming wealthier, more educated, and choosing to have fewer babies. More life options for women is a good thing. And logistically speaking, fewer people means less congestion and environmental pressure on the planet, not to mention lower housing costs.

Most importantly, Japan has the opportunity to set an example for other countries. It's the first nation to face this demographics sea change. If it navigates the crisis well, it can become a global leader for other nations, increasing its standing on the world stage.

For example, US population growth is also slowing, and the baby boomer generation will soon leave the workforce in droves. These new retirees can benefit from Japan's example of seniors living full lives 20 or 30 years past retirement.

It may seem bleak now, but Japan is working hard and the show's not over. As Rosabeth Moss Kanter once said, "The middle of every successful project looks like a disaster." In other words, give it time.