My first exposure to foreign cultures was through a Japanese classmate in kindergarten. Until then I had lived in a limited world, unaware of other cultures, countries, and the vastness of universe. But Takeshi expanded my horizons, introducing me to the culture of his home country, an interesting place called Japan.

Suddenly foreign cultures became a tangible reality. I learned that Japanese people ate raw fish and removed their shoes when entering homes. More importantly, I learned that my beloved M.U.S.C.L.E. toys originated from Japan where it was known as Kinnikuman and even had its own comic and cartoon!

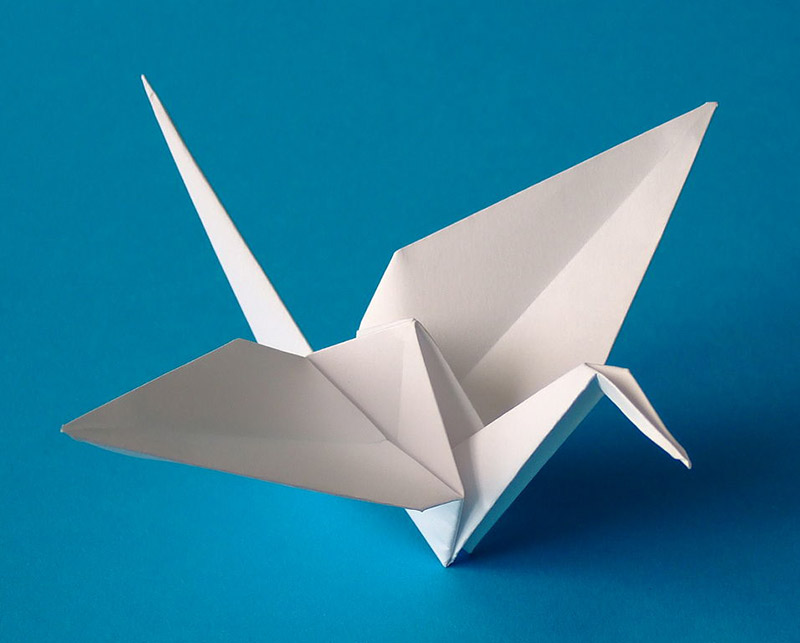

Takeshi also taught my class about origami – the Japanese art of paper folding. I recall being surprised by the delicate paper, overwhelmed by the detailed instructions, and impressed by Takeshi's finished product – a beautiful paper crane (that looked much better than my attempt, which looked more like a backhoe).

Little did we know that Takeshi's origami did much more than expose us to Japanese culture – it helped shape our developing brains. Recent research shows that origami is more than just a cultural pastime or art. In fact, it might be the best activity for children's developing minds, making it perfect for school curriculums everywhere.

The Developing Child

Although children develop at varying rates, every age has developmental benchmarks. For example, four-year-olds can clean-up, dress themselves, and begin to show hand preference. The average five-year-old can grip utensils, write and draw, and begin to comprehend rules. These stages can be found in any child development textbook, but BrooksHealth.org presents a great overview in their pamphlet entitled, A Guide To Your Child's Gross & Fine Motor Development.

As a kindergarten teacher I find a clear-cut distinction between the age groups' abilities and the accuracy of these benchmarks shocked me. For example songs and dances work best with the four-year olds because they cannot yet grasp a game's rules and structure. However, with only a year's difference between them, five-year olds can understand instructions, follow rules, and can therefore play games. Due to these acute developmental differences, lesson-planning varies by age group.

Nature versus Nurture – Providing an Appropriate Learning Environment

Although the nature versus nurture debate – whether genetics (nature) or environment (nurture) takes preference in determining a child's development – continues today, most experts agree that opportunities for children to practice and improve their developing skills are imperative. As James Arthur and Ian Davies explain in The Routledge Education Studies Textbook, "Nowadays even the most devoted environmentalists or hereditarians admit that both nature and nurture play an obvious role in the development and functioning of human intelligence" (99).

Skills can be divided into two main categories, cognitive and motor. Sociability and following instructions, rules, and routine make up cognitive skills while motor skills consist of physical abilities like hand coordination, balance, and dexterity. Although cognitive and motor skills differ, they can develop together in the brain. Bill Jenkins, Ph.D. of Scientific Learning explains, "These abilities (cognitive and motor) were attributed to separate areas of the brain… But… research show(s) that both (cognitive and motor areas of the brain) could be activated during certain motor or cognitive tasks."

It's no surprise that nursery schools and kindergartens facilitate activities and environments to spur a young child's development in both respects. Japanese kindergartens emphasize real-life situations like cleaning up, serving lunch, and packing up. Since students are together throughout the day and cooperation is encouraged, social interaction is constant. As a result, cognitive skill development is naturally incorporated into a student's school life. More deliberate activities like rajio taisou (calisthenics), arts and crafts, dances, and te-asobi (hand-play) facilitate motor development.

Origami, a kindergarten staple, facilitates both cognitive and motor skill development, making it an excellent activity for children. At times teachers incorporate paper folding into lessons as a classroom activity. But constant access to instruction books and origami paper encourages children to explore and practice the activity on their own during free play. With widespread accessibility and practice, Japan has embraced origami as an essential element in providing an appropriate learning environment.

Origami and the Developing Brain

But Japan isn't alone in recognizing origami as a developmental tool. In fact, Amera Khanam of A Learner's Diary explains that "Friedrich Froebel, the godfather of kindergarten, "was the first to introduce origami into formal education… Froebel recognized the value of children learning through play and exploration. He considered the manipulation of the paper as a means for children to discover for themselves the principles of math and geometry."

Mr. Froebel pinpointed origami as a perfect activity for childhood development. And he isn't alone, recent research has served to bolster the claim.

Hagit Shalev of Theragami (New York's Educational-Therapeutic Origami Program For Children and Adolescents) wrote, "In this learning by doing activity, (in which co-ordination and motor control play an important part), there is a continuous interaction of the action and thought process. Children watch how each fold leads to a more advanced one and how together they all progress to create a life-like pliable material… Origami is a method of active research. There is a gradual progression, a sequential order, research into new relationships of folds, and creative possibilities which encourage the advancement of new ideas."

Katrin and Yuri Shumakov of Oriland performed extensive research on origami's effect's on children's brain activity in their 2000 study entitled "Left Brain and Right Brain at Origami Training." They reported, "Our findings allow recommending… origami training for (the) development of motor, intellectual and creative abilities of children…. The training of origami… causes intensive interaction of brain hemispheres and… effectively develops motor, intellectual and creative abilities (of) children."

Leveling Up

Origami's varying levels of difficulty provides another benefit – tiered learning. As A Guide To Your Child's Gross & Fine Motor Development shows, children use mastered skills as a springboard for learning new skills. While children master specific origami projects, a child will never master origami – there is always another, more difficult project waiting to be challenged.

Kurt W. Fischer of The University of Denver explains, "(Children's) development is relatively continuous and gradual, and the person (child) is never at the same level for all skills. The development of skills must be induced by the environment, and only the skills induced most consistently will typically be at the highest level that the individual is capable of" (Fischer, 480). As children level-up, they need new, more complex activities to push their development.

My previous article on beigoma (battle tops) exemplifies the process. At first, four year olds are given simple tops that involve pulling a string or spinning the stem between their palms. These tops familiarize the younger children with the top's physics and skill sets needed to make them spin. The experience with those tops will be reapplied and expanded on when the children are five years old and they learn to use more difficult tops.

With no limit to its complexity or difficulty, origami proves to be the perfect developmental activity once again. Some origami activities require only a few simple folds (like this mouse). Others include detailed instructions with numerous, complex folds (like this elephant). In fact, some origami is so complex one can continue the practice into adulthood. There's no end to the challenge – just check out this rose!

Mr. Fischer continued, "The level of skills that are strongly induced by the environment is limited, however, by the highest level of which the person is capable. As the individual develops, this highest level increases, and so she can be induced to extend these skills to the new, higher level."

When practicing origami, a child improves at his own pace. Once a simple origami is completed, the child can move onto more complicated ones, constantly using mastered skills to build new skills and level up. And with a wide range of difficulty, the activity suits children at all ages and all skill levels.

Children and Origami

From a teacher or parent's standpoint, origami is a perfect activity to foster a child's development. But there's another benefit as well – (most) children love origami. What makes origami such an enjoyable activity?

Origami caters to a child's interests. Children can create anything through origami – from useful wallets and protection amulets, to cool bugs and cute animals, to toys like shuriken, swords, and tops. One boy even made a Nintendo 3ds which could play any game imaginable (or should it be – only games imaginable?). With so many options available, children can choose something that they want to create. This makes origami more motivating than other, by-the-book school activities.

Origami empowers children with choice. Children choose what to make, what kind of paper to use and what color to make it. Once the origami is complete a child has control over it and can chose what to do with it. Many of my students use their origami as a way to show they care by giving them as presents. The Sadako Sasaki story of One Thousand Cranes famously exemplifies origami gift giving.

Origami builds self-confidence. Mistakes are forgivable as paper can be unfolded and refolded. Completing a project creates a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. Furthermore, with the finished product at hand, there's a sense of instant gratification. There's no wait for glue, paint or clay to dry. A child can instantly enjoy the fruits of her labors.

Perhaps Hagit Shalev of Teragami put it best, "To the unsuspecting child, the transformation of the flat sheet of paper into a three dimensional form, using only two hands, seems almost magical."

Origami For All

Okay, maybe doing origami once in kindergarten wasn't enough to actually shape my brain. But Takeshi's well made crane showed that his consistent practice paid off – he could follow the directions and make the correct folds in the paper. I never did origami again (until recently) so I never leveled up – but the experience left a lasting impression.

Connecting my childhood experience to what I know today, Japan and origami seem like the perfect fit. Learned patience and attention to detail can later be applied to cultural practices like flower arrangement, bonsai trees, tea ceremony and writing kanji – as well as the Japanese workplace. Therefore paper folding is the perfect activity to start children on their way to successful adulthood in Japan.

Yet, with all its benefits there's no reason origami shouldn't be embraced as an educational tool outside Japan as well. It doesn't take much – a piece of paper is all you need to watch the rich and challenging world of origami unfold (or fold?) before you. In fact, most of you probably have the necessary tools in your pocket right now! Get folding!