A 52-year-old resident was found dead in his Kitakyushu home. While investigating the man's death, officials discovered a journal. The man was starving, and in his final entry he penned:

"3 a.m. This human being hasn't eaten in 10 days but is still alive…I want to eat rice. I want to eat a rice ball."

Headlines swept across Japan in Fall 2007. Perhaps society failed him. Maybe he was proud. Either or, this man died for lack of food. The incident stirred national debate, and not for the mere fact that the man had starved. It was that he had died in hope of eating onigiri.

What Is In A Word?

onigiri is a word with vague origins at best. A Japanese sushi chef, part of my extended family, often teased me saying that onigiri was not actually o-nigiri お握り [a grasp of rice], but oni-giri 鬼義理 [demon-obligation]. As a child, this creepy humor freaked me out, not because I was superstitious, but because he actually believed it. Having a shrine devoted to Inari, the kami of rice within his bar, he hoped to find supernatural stipulation.

Later I discovered that Japanese was more often about the spelling rather than enunciation. And for someone who has watched The Scripps National Spelling Bee, the importance of word origin is sacrosanct to spelling. Is it cliché then, that many Japanese people routinely ask English speakers, "How to spell?"

Japanese is little different, as countless observations reveal Japanese people slashing the air with extended index fingers as they form words in their mind's eye to understand word meaning through character identification. My ojisan understood this principle, clapping his hands and bowing his head before a pillar of rice and burning incense.

The Symbol Of Japan At Its Center

Searching the web, the onslaught of posts dedicated to the rice ball is astounding. There are endless pages chronicling preparation, from rice selection to nori wrapping, yet there is scant information in regards to onigiri's origin and innovation. What is documented, are wisps of history. In the 17th century, samurai consumed onigiri as battlefield-ready meals. 11th century Japanese writings casually mention rice ball consumption as a picnicking item.

"Rice balls for the retainers were set out in the garden." The Diary of Lady Murasaki (c. 973-c. 1020)

And not so ironically, that same right-leaning uncle proclaimed onigiri as Japan's first fast food. I laughed when he said this, but not aloud. He had a habit of claiming Japanese firsts of all sorts. Then he withdrew an old American pocketknife. Cutting through one of the rice balls he had set before me, he asked, "What do you see?"

I crinkled my nose as I spoke, "Umeboshi (pickled plum) and rice, doi!" This was apparently not, the answer. I was not a persnickety child, but the doi had my 8-year-old cousin in stitches.

Denying my youthful absurdity, her father wiped the blade upon his apron, folded and placed the knife upon the glass counter between us. He asked rhetorically if I knew the story of his knife. I did not answer. So he calmly turned the plate as he spoke, "I see a rising sun through a field of cherry blossoms."

My cousin cupped her hands around my ear. "Hinomaru." (Hinomaru = Flag of Japan AKA "Circle of the Sun")

Development To Modern Form

- 300BC to AD250 (Yayoi Period) Chimaki—Glutinous (sticky) rice wrapped in bamboo leaves introduced from Mainland.

- 250 to 538 (Kofun Period) Glutinous rice pervades.

- 538 to 710 (Asuka Period) Glutinous rice pervades.

- 710 to 794 (Nara Period) Pre-chopsticks, the sticky rice "ball" gains popularity.

- 794 to 1185 (Heian Period) Tonjiki—Glutinous rice shaped into snack sized squares emerge.

- 1185 to 1333 (Kamakura Period) Glutinous rice persists.

- 1333 to 1336 (Kenmu Restoration) Glutinous rice persists.

- 1337 to 1573 (Muromachi Period) Hard earthenware is introduced from Korea. Non-glutinous (Japonica) rice supersedes sticky rice as dietary staple. Nori introduced as wrapping.

From this point, the popularity of Japonica rice outpaced sticky rice. It was only in the 1980's when the development of automated rice ball machines solidified the ubiquitous triangle shape into the minds of the masses.

The Experts Remain Divided

Some foodie scholars argue that Korea's Jumuk Bap predates all other iterations of rice ball. Chinese claims are refuted by demonstrating their refusal to eat cooled rice for several centuries prior to onigiri. Yet one thing is undisputed: the modern day Japanese rice ball is the standard bearer in proliferation, quality and variety. It is onigiri that the world thinks of when speaking about the rice ball.

Through the wild expansion of Family Mart in Southeast Asia, to the quaint Mussubi restaurant in Paris, to the flourishing Western adoption of Japanese food, there is but one sort of rice ball to be found: onigiri.

In lieu of the above-mentioned, the one outstanding, often overlooked fact, proving once and for all that onigiri is and will remain Japan's greatest food innovation, are the Japanese themselves. This is a circumstance in which the people define a food, not the other way around.

Saying Rice Means Eating It

Time to hit the streets, and by streets I mean immediate Japanese friends, family and co-workers. I posed the question: What makes onigiri especially Japanese?

Everyone had an opinion, with most answers embedded in nostalgia. They remembered school field trips when mom had packed simple salted onigiri within their boxed lunches. Another shared the story of summiting Mount Fuji, and the well-deserved mountain top treat our uncle prepared the night before. There were those who reminisced on the time separated from their families while on business or at school and the comfort they felt biting into a store bought onigiri being so far away from home.

The irony was that it did not matter if the onigiri was good or bad. When asked, all of my respondents seemed rather unimpressed with the onigiri they recounted. My cousin who shared her story of eating a rice ball atop Fujisan said that the onigiri was mediocre at best, "The nori wasn't kept separate so it was soggy, and the rice was a bit dry." But her fondness for the memory will always be associated to that rice ball.

I understood this sentiment, often associating events, people and places with food. My delight in expressly refrigerated German chocolate cake is ever connected to my sixteenth birthday. I often reminisce about barefooted Swedish summers when eating strawberries. And then, there's my association with onigiri.

When I think of the rice ball, I remember picnics with my family, the lack of extravagance and the simplicity of sharing onigiris prepared by my mother. The rice ball is profoundly Japanese in its design and consumption. All of the people I spoke with remembered events, because that event involved onigiri. In the rice ball's singularity, it is a transcendental food. Everyone can relate to the humble onigiri and in turn, to each other.

Sentimental Rice

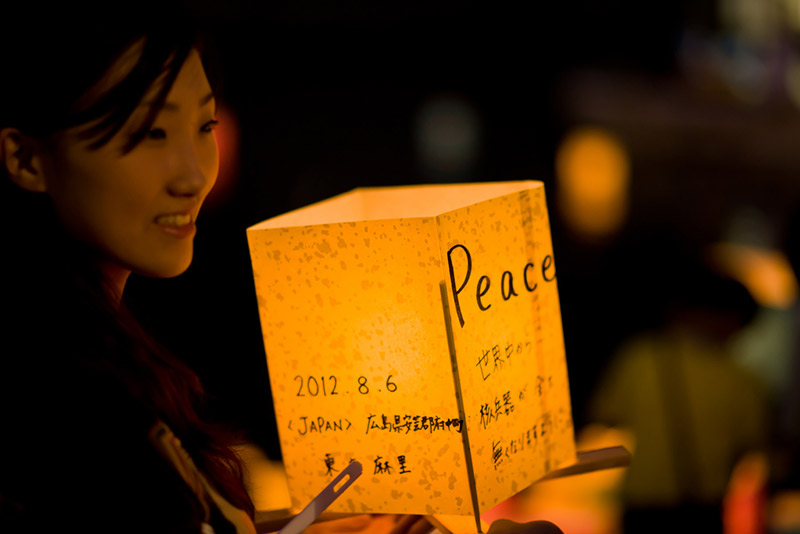

Onigiri holds this nostalgic place in the hearts of most Japanese I know. No matter their story or association, the rice ball always signifies that moment of pause, an absolute moment of self-reflection. This was the key to unlocking their nostalgia; that no matter what one was doing, be it in good company or alone, in joy or in sorrow, the onigiri transported their minds to tranquility.

"Yeah, it's just a ball of rice, but…" my friend Yo-yo would say with a sidelong glance, "Rice is life." She reflected on her own grandmother's wartime struggle to source enough grains in a week to make a single rice ball. "That was a real treat. You should see her face when she tells it, my grandma's delight in such simplicity. I cannot imagine sharing onigiri, let alone splitting it four ways." Yo-yo smiled serenely from some far-off place.

I understood her. The nostalgia enraptures us as we stand before the hum of an open cooler. The distant memory of sweeping up grains of rice to this moment's no want for lack of choice grants us pause. A battalion of perfect pre-made triangles are stocked and color-coded in every variety imaginable. We do not purchase any, but take comfort in knowing they are there.