In every culture there are beliefs about animals that are so basic, we don't even quite realize that they are folklore. In English we talk about the lazy pig and the wise owl, even though most of us have never met one personally, and have no way of knowing whether swine are really shiftless or owls actually have a lick of common sense. It just seems to go without saying that that's the way they are.

But then you encounter animals in another culture and it's not so obvious. You don't have to be interested in Japan for very long before you stop and wonder: What's up with all the foxes? Are they good, are they bad, why are they so important, and why are they in my udon?

The fox (kitsune 狐) plays a role in Japanese culture that's unusually rich and complicated. Beliefs that developed when people lived much closer to nature persist in stories, festivals, and language. Even in these rational times, the fox has a magical aura that still lingers.

And if you want a quick summary before diving in deep into fox lore, check out our video that encapsulates kappa lore in under seven minutes:

Done with the crash course?

Good. Because it's time to get extra friendly with this foxy demon god. If wake up naked in a pile of leaves, don't say we didn't warn you.

Inari Fox of the Gods

All foxes have supernatural power. There are good and bad foxes. The Inari-fox is good, and the bad foxes are afraid of the Inari-fox. – Lafcadio Hearn, Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, 1894

If you've ever been a tourist in Japan you've seen statues of foxes at Shinto shrines. It's a little odd from an American perspective, where animals are not much involved in religion, except maybe those cows and camels admiring Baby Jesus in nativity scenes. Surely the Japanese don't worship foxes?

No, not exactly, although it kind of depends on who you ask, as we'll get to later. When you see those foxes, you're at a shrine dedicated to the god inari 稲荷, who's worshipped everywhere from tiny roadside shrines to major tourist destinations like the famed Fushimi Inari in Kyoto. More than a third of the recorded shrines in Japan are Inari shrines and, aside from the fox statues, the obvious symbol that indicates "Inari shrine" is red torii gates.

Entire books have been written on the varied meaning and significance of Inari, but the one thing everyone agrees on is that this god is connected to rice. Given the importance of rice in Japan, Inari is obviously a big deal. Often people pray to this god for business prosperity – perhaps, as the early Western Japanologist Lafcadio Hearn observed, because all wealth in the old days was counted in measures of rice.

OK, but what's the fox got to do with it? The fox is associated with Inari as a symbol, a messenger, a servant, or maybe more. Whatever it is, now it's impossible to tease the two apart, although no one's quite sure how this connection arose – the earliest historical records of Inari worship, before the tenth or eleventh century, don't mention anything about foxes.

The simplest explanation seems to be that rodents eat rice, foxes eat rodents, so foxes could have been seen as protectors of rice. But some of the associated beliefs have no such rational explanation. Take the fact that worshippers at an Inari shrine will commonly make an offering of abura-age, those thin slices of fried tofu with sweet soy sauce flavoring. It's supposedly the favorite food of foxes. That's why udon with fried tofu topping is called kitsune udon, and fried tofu pockets stuffed with sushi rice is inari-zushi.

Foxes are naturally carnivores, so this is pretty odd. There's no agreed-upon explanation for this belief, and again, no clear historical record of how the tradition developed. Animals do sometimes like foods they'd never get in nature – dogs are crazy about peanut butter, for example, and cats love tuna despite the fact that they hate to get near the water. But this one doesn't stand up to empirical testing: one author writing a book about Inari was told by a priest that he saw a TV program where a fox was offered meat, fish, and fried tofu, and – no surprise, really – tofu was the animal's last choice.

The Goblin Fox

But only aged and wise foxes have power to act as people for a prolonged time; incidentally, age and wisdom do not imply benevolence. - U. A. Casal, The Goblin Fox and Badger, 1959

Though Inari foxes are associated with a powerful deity, they're also believed to have less benevolent counterparts. youkai 妖怪 is a class of strange beings that has no real translation into English, and includes everything from household objects that come alive to, evil children offering you tofu, to long-nosed winged humanoid demons. And the kitsune fox demon is part of the yokai. The stories about their powers are strange and varied, involving everything from odd human behavior to unusual weather.

Fox Illusions

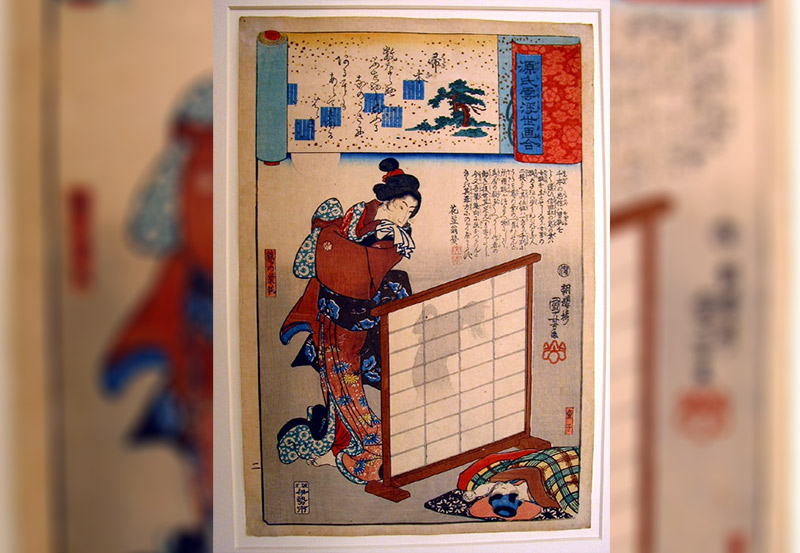

Kitsune can make themselves appear to be humans, usually with mischief – or worse – in mind. A fox might pose as a distressed woman traveller or a monk on a pilgrimage and, after a kindly villager is convinced to take it in, the next morning the villager finds that all his food and valuables have been stolen. To add insult to injury, the kitsune may shave his head bald. Much nastier, though, foxes were said to use these abilities to tempt people to go places where they were likely to get killed.

The fox isn't the only animal yokai that can shape-shift, but they have a special predilection for appearing as a beautiful woman in order to deceive human men. Oddly, in this case they don't always have bad intentions. As Lafcadio Hearn tells it:

The fox does not always appear in the guise of a woman for evil purposes. There are several stories, and one really pretty play, about a fox who took the shape of a beautiful woman, and married a man, and bore him children—all out of gratitude for some favour received—the happiness of the family being only disturbed by some odd carnivorous propensities on the part of the offspring.

Looking like something else is only half of it, though. Kitsune can orchestrate full virtual-reality experiences, making people think they're in houses that don't exist or experiencing an earthquake that isn't really happening. As they kept up with modern technology, foxes were said to make phantom trains run on the earliest railroads, disguise themselves as cars, and deliver fake telegrams. Belief in this ability was so strong that Hearn tells of peasants who would assume that a truly strange experience was a fox-illusion rather than trusting their own eyes:

The most interesting and valuable witness of the stupendous eruption of Bandai-San in 1888—which blew the huge volcano to pieces and devastated an area of twenty-seven square miles, levelling forests, turning rivers from their courses, and burying numbers of villages with all their inhabitants—was an old peasant who had watched the whole cataclysm from a neighbouring peak as unconcernedly as if he had been looking at a drama. He saw a black column of ashes and steam rise to the height of twenty thousand feet and spread out at its summit in the shape of an umbrella, blotting out the sun. Then he felt a strange rain pouring upon him, hotter than the water of a bath. Then all became black; and he felt the mountain beneath him shaking to its roots, and heard a crash of thunders that seemed like the sound of the breaking of a world. But he remained quite still until everything was over. He had made up his mind not to be afraid—deeming that all he saw and heard was delusion wrought by the witchcraft of a fox.

Putting the two abilities for illusions together, a fox may pose as a beautiful woman and lure a man to her remote, luxurious home for a night of passion. But when he wakes up the next morning alone, he is lying in a graveyard, with the leftovers of his sumptuous meal revealed to be a pile of rotting leaves and worse.

Possession

Being deceived by a fox is bad enough, but being possessed by one sounds far more unpleasant. Foxes were said to possess people for a variety of reasons. They might want revenge for some offense, ranging from killing its cub to disturbing its afternoon nap. They might want something done for them that requires manipulation, like having a little shrine built to it, or getting one of its favorite foods like fried tofu or red rice.

The effects could be quite nasty – pain, madness, hysteria, running naked through the streets, collapsing, and frothing at the mouth. But in other cases, the result was simply behavior that was inappropriate or odd: using bad language, throwing money around like a millionaire, barking or yipping, behaving violently, or spitting. One scholar described a particular sort of fox that would cause the possessed person to barge into houses and annoy sick people, blurt out secrets, and mess up silkworm colonies.

Many of those are things that people would probably not do voluntarily, and today the victims would likely be sent for mental health treatment rather than exorcism. But in other cases, you have to wonder if fox-possession was sometimes a handy excuse: there were alleged victims who ate a whole lot of fried tofu and other favorite foods and insisted it was the fox that was the glutton.

Fire and Water

The marriages of foxes (to each other, rather than unsuspecting humans) are said to account for two odd natural phenomena. One is kitsune-bi (狐火, meaning "fox-fire"). This is what's called will o' the wisp in English – mysterious flickering lights seen at night in natural areas like forests and especially wet places like bogs and marshes.

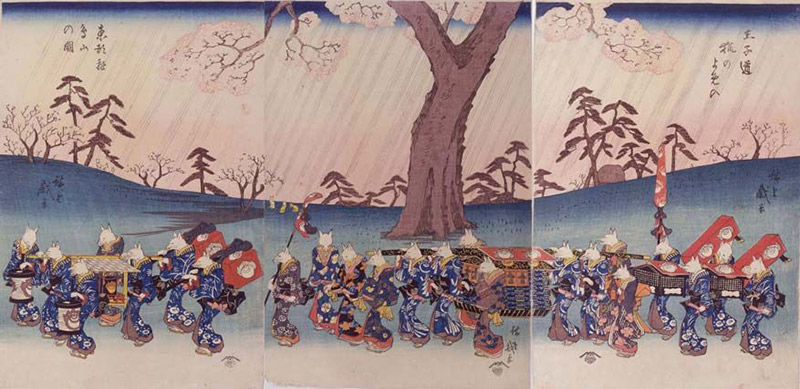

Sometimes a large outbreak of this phenomenon would look a like long procession of flickering lanterns. These reminded people of a traditional wedding ceremony where the bride was escorted to her new home by an entourage carrying lamps, so were said to be the wedding celebrations of foxes. There's never been any accepted scientific explanation of the will o' the wisp, and the processions always disappeared when people tried to get near and find out for sure, so who's to say they weren't?

Foxfire is only rarely seen today, maybe because natural areas aren't what they used to be, maybe because foxes were tired of the paparazzi trying to get close to them. So nowadays "fox's wedding" more commonly has another meaning: They're thought to be holding their weddings on days when it's raining out of a clear blue sky, what we much more boringly call in English a sun shower.

How Not to be Fooled

For one thing, a spook-fox will always emit a certain luminosity, and even on the darkest night his human shape will stand out so clearly that the colour of the hair and the pattern of the kimono is plainly discernible at the distance of some six feet. Hair and pattern show up as if a fire were glowing beneath them! Usually, also, the face of the human apparition is unnaturally long. -The Goblin Fox and Badger

Fortunately, there are ways to tell that a person is really a fox in disguise. The tail is a weak point – reflections in a mirror or pool of water may show a tail, and young foxes who are less experienced at the illusions may have trouble concealing their tails. Shadows may also reveal their true nature – a shadow falling on water shows the true shape of the fox.

Another trouble foxes have – which is maybe the only thing here that makes perfect logical sense – is speaking convincingly like a human. Hearn writes:

A fox cannot pronounce a whole word, but a part only—as "Nish . . . Sa. . ." for "Nishida-San"; "degoz . . ." for "degozarimasu, or "uch . . . de . .?" for "uchi desuka?"

Supposedly "moshi-moshi" was a particularly difficult tongue-twister for them, so unless you want to be mistaken for a fox, make sure you never say "moshi" just once.

But the best defense against foxes is to have a dog. Foxes are said to be terrified of dogs because dogs aren't fooled by illusions. They will bark and let everyone know what's up, sometimes even causing the fox to lose its human form. Dogs were also even used in cures for possession: Smear fish paste all over the victim and have a dog lick it off. The fox will be so repulsed that it will leave the person's body. (And who could blame it?) Less disgusting approaches include protecting against possession by carrying a dog tooth or writing the kanji for "dog" on a child's forehead.

It's not a bad idea to be nice to foxes if you can, because they can be grateful (and given everything they are capable of, you probably would rather have them on your side). They'll even bring little gifts, as best they can. Lafcadio Hearn tells of a man who saw a fox being chased by dogs, and chased the dogs away with his umbrella:

On the following evening he heard some one knock at his door, and on opening the to saw a very pretty girl standing there, who said to him: "Last night I should have died but for your august kindness. I know not how to thank you enough: this is only a pitiable little present. And she laid a small bundle at his feet and went away. He opened the bundle and found two beautiful ducks and two pieces of silver money—those long, heavy, leaf-shaped pieces of money—each worth ten or twelve dollars— such as are now eagerly sought for by collectors of antique things. After a little while, one of the coins changed before his eyes into a piece of grass; the other was always good.

If you see a pure white fox, that's the good Inari fox, so you don't need to worry. (Except… if a yokai fox can make itself look like a human woman, wouldn't it be even easier to simply change color? That hasn't happened in any of the stories I've read, but now I've gone and given them the idea, so proceed with caution.)

Foxes in the Family

Being nice to foxes is one thing, but having too close a relationship with them is definitely not worth the price. It was once believed that certain families owned foxes, and in return for being fed, the foxes would use their supernatural powers to the owner's benefit. That sounds like a great deal, but apparently not so much. For some reason they usually came in large numbers – seventy-five was typical – so feeding them was a huge expense. And, being foxes, they weren't particularly trustworthy servants, so they'd often do things that got their owners in trouble, like stealing.

The real problem, though, was that reputed fox-owners were ostracized by the rest of society. Hearn wrote of the effects in the late nineteenth century:

Intermarriage with a fox-possessing family is out of the question; and many a beautiful and accomplished girl in Izumo cannot secure a husband because of the popular belief that her family harbours foxes.It affects the value of real estate in Izumo to the amount of hundreds of thousands. The land of a family supposed to have foxes cannot be sold at a fair price. People are afraid to buy it; for it is believed the foxes may ruin the new proprietor.

Amazingly, as late as the 1950s there was a case in Shimane, where fox belief was particularly strong, of a couple committing double suicide when they were forbidden to marry because girl came from a fox-owning family.

The Fox in Real Life

The fox has played such a big role in the imaginative life of Japanese people, one has to wonder why. What relationship did people have with this animal long ago? The fox isn't a predator that we needed to fear, we didn't eat it, and it didn't compete with us for food. Perhaps it played a role keeping down pests in rice fields, but could that have developed into such a complex and sort of contradictory body of beliefs?

Maybe it's a mistake to assume the reasons have to be practical ones. The fox is an unusual canine, more like a cat in many ways – solitary rather than social, a solo stealth hunter of prey much smaller than itself. Other similarities to cats include claws that partially retract, eyes that reflect light at night, and behaviors when stalking prey and in response to threats. There's also the oddity that it has such a bright-colored coat rather than the inconspicuous coloring more useful for a predator.

People who lived closer to wildlife, who had more of a chance to observe this animal, would surely have noticed these features. Perhaps it's not going too far to imagine that this double catlike-doglike nature influenced the legends of the fox's shapeshifting and trickster nature.

The red fox is found in more places than any other wild canine, living all over the Northern Hemisphere from the Arctic circle and the steppes of Asia to Central America and the north of Africa, and Japan isn't the only place where it became part of the language and folklore, with similar connotations. Where Japan has shapeshifting fox wives, we have "foxy" as a term for a seductive woman, and "vixen" (which means female fox) has been used since medieval times to refer to a woman who's attractive but not very nice. The fox is a trickster figure in the folklore of some Native American peoples, and also associated with fire in some. In English "outfox" means to trick or outwit. All over the world, it seems, people read the same sorts of meanings into the behavior of this animal.

Another reason the fox is associated with cunning and trickiness may be its ability to live among us without being seen. In Hokkaido, where they've got their own subspecies of red fox, it's used as a symbol of unspoiled nature. Which of course means tons of awesome souvenirs:

But in a world where there's so little unspoiled nature that tourist boards use it as a selling point, foxes know better than to stick to the wild. They've always thrived where humans are committing agriculture – after all, that's the whole association between Inari, rice, and foxes. And their natural preference for edge environments – places where woodland and more open space meet – means that by building suburbs where there were once dense forests, we've actually created fox habitats.

So there may be foxes closer to you than you think, but magical or not, better to keep away as best you can, especially from those Hokkaido foxes. They carry a nasty parasite, a kind of tapeworm called echinococcus that can actually be fatal to humans. That's another kind of possession you really don't want to mess with.

Good Fox/Bad Fox/Real Fox

So far we've mostly looked at the relationship of the different sort of foxes, real and less real, to humans. But how do they relate to one another? As some of your Facebook friends say, it's complicated.

There are other gods to whom a particular animal is sacred and symbolic, but for some reason the Inari/fox connection is different. Hearn noticed this in the nineteenth century, and didn't much care for it:

Indeed, the old conception of the Deity of Rice-fields has been overshadowed and almost effaced among the lowest classes by a weird cult totally foreign to the spirit of pure Shinto—the Fox-cult. The worship of the retainer has almost replaced the worship of the god.

Did people really think they were worshipping a fox? Do they still believe this today? The scholar Karen Smyers, while writing a book about the worship of Inari, tried to figure this out, and the answer she came up with seems to be "it depends on who you ask."

On the one hand, the priests that she interviewed all said basically, "heck no, no way!" The party line was that the fox was a messenger of the god only. But the mere fact that there has to be a party line, and that priests have to put effort into discouraging the alternative, has to mean something.

Smyers thinks that the official view is probably pretty recent, going back to the Meiji period, when there was an attempt to purge Shinto of its animistic elements, as part of the push to make Japan a Westernized nation. This attempt clearly didn't take as far as the average worshipper went. Talking to devotees, she discovered that some did see Inari as a fox, although they differed on whether the god was benevolent or terrifying. The priests had to deal with this belief all the time, and in some stories, seem resigned to it:

One day a man brought two dusty old fox statues to an Inari shrine to be burned with other retired sacred paraphernalia and rather loudly announced that he had been worshiping them as Inari. The priest grimaced, explain in a rather curt fashion that Inari was not a fox, but said that he should have a prayer service anyway.

The yokai foxes get mixed up with the religious side as well. In the old days, cases of fox-possession were brought to Inari shrines to be cured, although the priests insisted Inari had nothing to do with it. The connection between yokai foxes and fire also rears its head: Oji Shrine is associated with fire prevention, and a fox saved Daitsuji Temple in Nagahama from a fire and people still offer her fried tofu in thanks.

Real foxes were also seen to have a connection to Inari shrines. Shrines were sometimes built over a fox den, or where a wild fox had done something odd or useful. Police worshipped at one built in 1923 in Kobe, where a fox had unearthed the weapon in a murder case. Live foxes were fed offerings of fried tofu at shrines, and in some places, they still are.

And Inari was sometimes considered responsible for the behavior of real foxes: one Edo-period story tells of a boy who went to an Inari shine and beat on it with sticks and yelled at it because a fox had stolen his chicken. The fox reportedly returned the chicken, and although it seems doubtful it would have been in a useful condition, sometimes it's the principle of the thing, you know?

The Fox Today

As the real fox has adapted to modern life, so do the folkloric ones. Authors of fiction and manga and anime put their own spin on kitsune, and some of these can even make their way into tradition. Multiple tails are traditionally a sign of great magical power, but a blogger who researched the now-common idea that the number of tails increases with age and rank concluded that it probably originated in a modern fantasy series.

Festivals persist, such as one at Oji in Kita, Tokyo, once supposedly a site where kitsune-bi was often seen, and where tradition said that foxes from all over the region gathered on New Year's Eve. Now, people from all over gather in fox masks for a parade.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Lafcadio Hearn predicted that western education would eradicate belief in the supernatural qualities of foxes. That hadn't happened by the 1950s, when one folklorist had no trouble finding believers, although even in those days it was often one of those things that happened to the friend of a friend:

They openly admit their fear of being bewitched. Nobody is ashamed of it, and if an uncomprehending foreigner laughs at the superstition, examples are immediately forthcoming of "well-authenticated" cases, or at least of people who knew people whose friend was once fooled by a fox.

By the 1990s when Karen Smyers was doing her research, people would tell her about things that happened to their grandparents, or that happened to them as children, not contemporary stories. She wondered sometimes if their answers were basically edited for her as a foreigner, though, and found that people seemed to be uncomfortable with the notion that she was hanging out with so much fox stuff:

Japanese people regard this kind of talk as old fashioned and superstitious. But the figure of the fox still retains some of its sacred and dangerous aura- at least to judge by the comments I heard when I talked to people about my research or showed them my extensive collection of fox statues. The idea that I was in such close touch with all those foxes seemed to make otherwise rational people rather nervous.

Whether you're a believer or not, it's probably best to be careful, as she found from her own experience when writing the part of her book about how foxes have modernized their methods over history:

I never heard of any computer-related mischief of foxes, but surely they are working on it.*

*While working on the final revisions of this text, I deleted this sentence as somewhat gratuitous – and soon thereafter lost the entire chapter and the backups as well.