Other parts of the world might be gloomily declaring that print news is circling the drain, but not in Japan, where newspapers have morning and evening editions and newspaper circulation rates are the highest in the world. (Japan’s top newspaper, the Yomiuri Shinbun has a circulation of about 10 million. Compare that to the 2 million of The Wall Street Journal and you start to get a sense of scope.)

But even though Japan is rocking the Casbah when it comes to the number of newspapers people are reading each day, there’s some serious work to be done with the reporting in those papers. According to Reporters Without Borders, Japan dropped 31 places in the World Press Freedom Index in 2013. Kind of strange for a liberal democracy, right? Welcome to the secret world of “kisha clubs.”

Kisha Clubs: What They Do And How They Do It

Kisha 記者 or “reporter” clubs are exclusive groups of reporters from major Japanese newspapers, like the Yomiuri Shinbun and the Asahi Shinbun, who set up camp in government and political party offices. The clubs receive press releases from whatever agency or business they’re assigned to cover. (Usually the agency’s PR offices are right down the hall from the kisha club – so convenient!)

The reporters in the club then edit or paraphrase those press releases to publish in their respective newspapers. Besides reading and revising a whole lot of press releases, kisha clubs also organize press conferences. (The life of a kisha club member: So excite; much report.)

And if you ask the Nihon Shinbun Kyokai (Japan Newspaper Publishers and Editors Association), there are super duper awesome reasons for keeping kisha clubs around. For one thing, they sort through gobs of boring political information, for which everyone is grateful. And although it leads to some pretty homogenous news articles – sometimes quite literally, with identical articles being printed in competing newspapers – kisha clubs receive news incredibly fast. After all, they’re in the same building as their sources.

They’re also a united front: plucky reporters against shifty politicians. Who would dare withhold political information when you have an entire kisha club staring you down? Kisha clubs run on the Wildcats principle…

We’re all in this together.

Majorly Bad Business

The problem is, well, journalism doesn’t really work that way. A journalist’s role is to hold feet to the fire, not give foot massages. (Okay, that metaphor got a little weird.) What I’m trying to say is that journalism works best when it works for the people and not for politicians. Kisha clubs, by their very nature, go against journalistic principles of working independently and maintaining an objective distance from news sources – not acting as a mouthpiece for them. And when these ideals get thrown out the window, all sorts of sketchy things start to occur.

We don’t even need to look very far for one particularly glaring example: the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster of 2011. (To catch everyone up to speed: A terrible domino effect occurred in March 2011 when the Tohoku earthquake hit Japan, which triggered a tsunami, which resulted in a catastrophic failure at the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant, releasing all sorts of radiation into the surrounding area.)

There was not much investigative reporting following the disaster and very little transparency from the government about subsequent radiation levels, evacuees, and how this disaster could have been averted.

The company in charge of these Fukushima power plants, TEPCO, has its own kisha club, but funnily enough, those kisha club reporters never quite got around to asking the questions the Japanese public most wanted and needed to know. Independent and foreign journalists also reported on the disaster. But, because they aren’t part of any kisha clubs, they were often barred from press conferences – one of the many kisha club rules – making reporting that much harder. Those independent journalists who did make it into these press conferences were often shouted down by kisha club members if they dared to ask any off-script questions.

Blackboard Agreements

Whether it’s your 1998 kid detective club devoted to Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen (cough) or your standard, government lapdog kisha club, clubs gotta have rules. (Insert your own Fight Club joke here.)

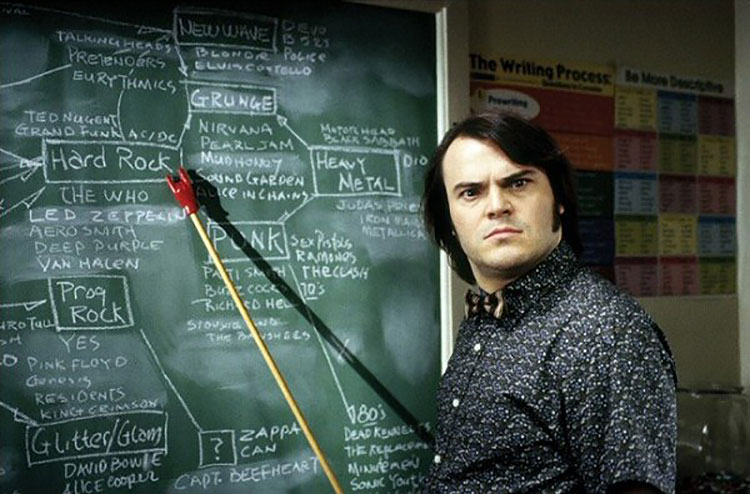

Besides not often allowing journalists from independent and foreign newspapers to participate in press conferences (let alone join a kisha club), there are also these things called blackboard agreements. Sometimes literally written on a blackboard, these are news items and topics that the club has agreed not to report on until a specific later date. The kisha club golden rule? You don’t “scoop” your fellow club member, even if he’s from a competing newspaper. (This is completely counter to how journalism normally works, where reporting a news story first is how many news media survive.)

Following blackboard agreements means having to maintain friendly relations with your sources as well as rival journalists. As with any club, you can get kicked out for not heeding club rules. Some kisha club members do break the rules on rare occasions, because sometimes it’s totally worth it. If a story is huge enough to be worth temporary club banishment because of all the papers it would sell, a kisha club member might just break the story anyway. Of course, there are ways to have your mochi and eat it too.

Weekly Magazines

Japan’s weekly magazines provide an outlet for news stories that may be stuck in blackboard agreement purgatory. A kisha club member will sometimes sell a blackboarded scoop to a weekly magazine, occasionally even writing the magazine article himself. (Club members have been known to sell news stories to foreign presses as well.)

The problem with having your news bombshell break in a weekly magazine as opposed to a newspaper is that Japan’s weeklies aren’t the most respected game in town. Weekly magazines are usually printed on cheap paper and are a whirlwind mix of news, sports, manga, celebrity gossip and porn. Sort of like if The New Yorker and The National Enquirer had a baby.

But, in the most roundabout way ever, once a story breaks in a weekly magazine and gains enough traction, the blackboard agreement becomes null and void and everyone can cover the story in their own newspapers.

But The Internet!

The Internet has decreased some of the power kisha clubs hold, and may yet be a game changer. Independent presses, foreign news sites and citizen journalists have all been part of a movement to provide news outlets that aren’t heavily influenced by government channels.

Independent online news sources like Days Japan and Free Press Association of Japan have started to pop up, but they’ve had some difficulty gaining traction with a Japanese public who are somewhat reluctant to trust online news media over traditional news outlets.

Unfortunately, things are probably going to get worse before they get better. In December of 2013, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe enacted a state secrets law, a move many consider a major step backwards for civil liberties in Japan. Under the new law, those who leak classified information will now face 10 years in prison and anyone found guilty of abetting a leak will get five. Kisha clubs also show no signs of going away.

But there have been some victories in all of this, too. For example, in 2001 Nagano Prefecture’s then-governor, Yasuo Tanako, abolished kisha clubs in the prefectural office. Any journalist, whether they were associated with a major newspaper or a small website, were given the same opportunities to gather information, no blackboard agreements required. And even though Yasuo Tanako has moved on from his Nagano roots, the kisha clubs he pwned haven’t come creeping back.

It’s been relatively easy up until now for kisha clubs to party down without anyone noticing. But with the continuing controversy over how the Fukushima catastrophe was reported in the news and the public outcry against Abe’s new state secrets law, the days of the kisha club may be numbered after all.