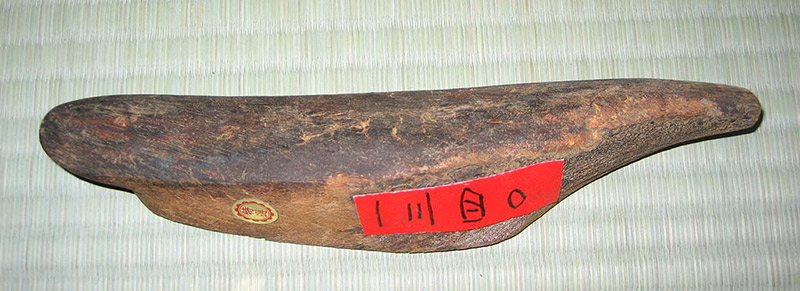

This probably doesn't look tasty to you. After all, it looks like a chunk of dirty wood:

With the above pic in mind, try not to freak out when I have to tell you, if you love Japanese food, you've eaten that thing many, many times. It's a dried fermented fish product called katsuobushi, and its flavor is the backbone of traditional Japanese cooking.

Katsuobushi is probably familiar to you in a different form: those papery-looking fish flakes sprinkled on top of cold tofu or okonomiyaki. But it has a less visible, very important role as a main ingredient in dashi, the broth used in traditional Japanese food. Unlike the soup stock used in most other countries, dashi takes only minutes to make – but that's only after the weeks or months it takes to produce katsuobushi.

Like many traditional foods and crafts, old-fashioned ways of using katsuobushi have been replaced by modern shortcuts in many homes, but the real thing is still hanging on and even spreading across the world.

Start with A Fish

Katsuobushi is made from a fish called skipjack tuna or bonito in English. It's katsuo in Japanese, reflected in its Latin name, Katsuwonus pelamis. As with any food with a long history, there are different types and many regional variations in how it's produced, but for the most traditional and elaborate kind, here's basically how it goes:

The fish is cut into four fillets and simmered for a couple hours, then deboned. Each fillet is then smeared with fish paste to fill in all the cracks and lines left where the bones were, giving it a smooth surface. Then it's smoked for about a month.

After that, the hardened hunk of fish is shaved to make sure the shape is perfect, and then sprayed with mold. No, really, it's okay – after all, many Japanese foods involve our little one-celled friends. In fact the mold used is related to kōji, the microorganism used to make sake, miso, and soy sauce – we wouldn't have Japanese food without it. The moldy fillets then spend about six months cycling between resting in a humid fermentation room and being dried in the sunlight. The result is what you see above.

Nowadays only a very small percentage of katsuobushi goes through that entire process. The simpler kind, called arabushi, is simply smoked for thirty days. As we see with many other foods and drinks like cheese and wine, the longer aging and fermentation processes are reserved for the most expensive, high-quality product, which goes under various names including hongarebushi, karebushi and shiagebushi.

Now What?

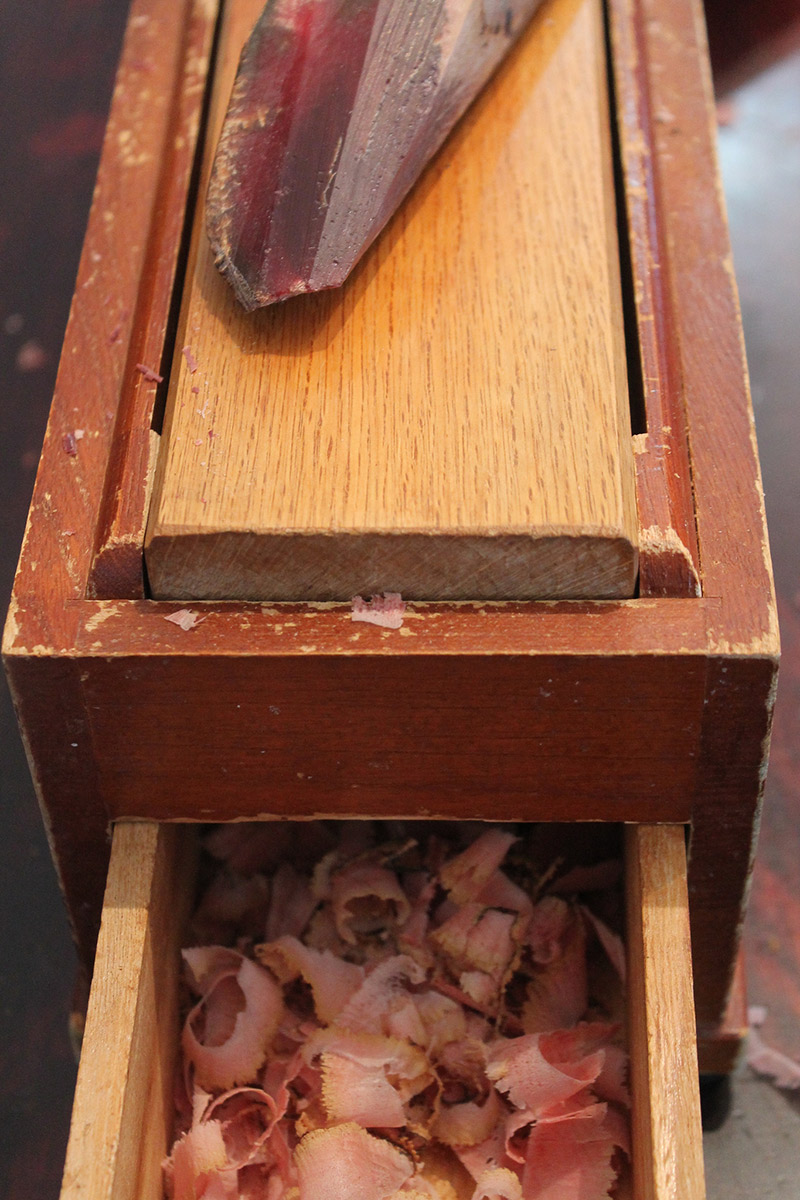

You can't just bite into a hunk of katsuobushi. Although I can't confirm this, I heard on an NHK TV show that katsuobushi holds the Guinness record for world's hardest food. If that's not true, it ought to be. This is why the form we're most familiar with is those flakes, because you've got to shave the hardened fish into paper-thin pieces to use it. The traditional device for producing the flakes by hand, a wooden box with a sharp blade on top and drawers to catch the shavings, is called a kezuriki, pictured above.

The flakes are eaten in many ways – on top of okonomiyaki (where they dance around from the heat), on top of takoyaki, on top of cold tofu, and inside of rice balls. But their most fundamental use is for dashi stock, which is used to make miso soup and is an ingredient in many traditional dishes. You may not know what dashi tastes like plain, but Japanese food wouldn't taste like Japanese food without it.

The most basic dashi is made of kombu seaweed and katsuobushi flakes. There are variations on how to do this, but basically, you soak a piece of kombu for while, then simmer it for ten minutes or so. Then turn off the heat and add the katsuobushi. The dashi is done once the flakes sink to the bottom of the pan (from half a minute to a few minutes, depending on who you read).

I always thought it was interesting and surprising that making dashi goes so quickly. Western soup stocks take hours of simmering to develop flavor, which made me wonder how the Japanese figured out how to make it so easily? But now I know the truth that dashi takes MUCH longer to make – it's just that the majority of the time is taken up in the production of the main ingredient long before it gets to your kitchen.

Why So Good?

Something like katsuobushi has been around since maybe the eighth century, with the first evidence of smoke-dying in the late 1600s and the fermentation process entering the picture about a century later. Various legends tell of some brave soul who found some dried, smoked katsuobushi that had gotten moldy, decided to eat it anyway, and discovered that it had become even more delicious.

But why? In my fridge, mold makes stuff worse, not better. What's going on? Here are some of the effects of mold in the process of making katsuobushi, according to the Tokyo Foundation:

Mold consumes the moisture in the meat to sustain itself, thus accelerating desiccation.

Mold has the ability to decompose fat, ridding the meat of both its fat and smell and converting the fat into soluble fatty acids. The process also takes the edge off the taste, enhancing the savor and aroma.

Mold breaks down proteins into amino acids and other nitrogenous compounds, which also increase savor (umami).

The coating of mold keeps off other microorganisms.

Mold breaks down the neutral fat and increases free fatty acids, resulting in a clear soup when katsuobushi shavings are boiled.

The result of all this is crazy full of umami. Umami is a trendy foodie concept now, but it's actually pretty old – and it originally came from Japan. In fact, dashi itself is where the concept comes from.

You may have heard that there are four primary tastes: sweet, salty, bitter, and sour. But it's generally recognized now that there's a fifth: umami, which is the flavor of savory, meaty things. One reason dashi has become central to Japanese cuisine is that it helps impart that kind of rich flavor to meatless dishes based on soy, vegetables, and fish.

In fact umami was first identified in 1908 by a Japanese scientist named Kikunae Ikeda who was thinking about why dashi had that meaty flavor. His analysis identified a component of kombu seaweed that he decided to call umami from the Japanese word umai, "delicious." (Ikeda built an empire on that work: basically he had discovered MSG, which he sold under the name Ajinomoto, now a giant food and chemical corporation.)

The combination of ingredients in dashi, because of the inosinic acid in katsuobushi and glutamic acid in kombu, have a synergistic effect that more than doubles that umami effect.

"One plus one becomes three or more on the umami scale," as one chef puts it.

Still, the very highest quality katsuobushi is about more than just a couple of molecules. There are subtle variations in flavor, with resulting differences in price (like in the photo above) and individual and regional preferences. Supposedly many cooks in fancy Kyoto restaurants prefer what's called Satsuma type made in Makurazaki in Kagoshima Prefecture. And individuals have individual preferences as well – dashi that tastes like mom made it can be a big deal. On my first trip to Japan, a friend took me to an udon place where she waxed ecstatic about the flavor of the dashi, a subtlety that was completely lost on me. And she's clearly not alone – it's even a trope you can find in fiction, like in a drama that I've written about elsewhere, where the proprietor of an old restaurant says she'll have to shut down if their traditional katsuobushi maker goes out of business, because their food would never be the same without it.

Modern Cheats

It's no surprise that such a complicated food would be the target of modernizers. If you've ever bought katsuobushi yourself, you probably bought it already shaved. That's a modern development, if you count the early 20th century as modern – which is fair to say given how long katsuobushi has been around. Before that, everyone had to have one of those shaver thingies to make the flakes themselves. The shop that's said to have first started selling katsuobushi in flake form in the early Showa era is still in business at Tsuskiji Market: Akiyama Shouten, which was founded in 1916.

It's also worth noting that nearly all of that pre-shaved katsuobushi in packets is the kind that's produced the fast way, by just smoking, not the kind that's fermented for six months. You're not going to find the best quality product in packet form, same as how you won't find the finest aged Parmigiano cheese pre-grated in a cardboard box with a shaker top.

It still counts as making dashi from scratch if you start with a packet of shavings, though, and you should try it because it's really easy. But of course nowadays there are even shorter shortcuts. Given how fast it is to make dashi I'm a little ashamed to say that sometimes I use these little tea-bag things that have the seaweed and fish and other ingredients in them, which you just pop into a pot of boiling water and steep for a while. They're really not bad though, compared to the fact that you can also buy dried instant granules and liquid concentrate. Can we all agree that there's no excuse for that? At least use the tea bag thingies, okay?

Not Dead Yet

Although there are worries about the preservation of Japanese traditional food culture and few people shave their own bonito flakes at home anymore, production of katsuobushi has actually been rising. And despite my own sad feelings about instant dashi granules, the reason for this increase is precisely the demand for its use in processed foods – not just convenient forms of dashi but entirely pre-made dishes like instant miso soup.

And while the majority of production is the simpler arabushi, there are producers committed to preserving the handmade product. One city, Yaezu, Shizuoka, where katsuobushi production is a major industry, has designated the art of making it the traditional way as a living cultural treasure.

Not only that, people are starting to make it overseas. This year, the first katsuobushi plant in France is supposed to begin production. The idea for the plant started when some visiting producers tasted a bowl of miso soup in Paris and were shocked at its lack of umami flavor. They discovered that the reason was that the French couldn't get the fancy kind of katsuobushi from Japan because EU rules prohibited the import of moldy foods. So they decided to build a plant to make it locally. Another chef is reported to be planning to make his own for an udon shop in Switzerland.

A famous American chef is even extending the technique to non-fish. David Chang of Momofuku in Los Angeles, who's known for being into fermenting anything he can get his hands on, has invented butabushi, processing pork in a similar way. Chang seems to be another brave man in the history of fermented foods, judging from tales of the initial attempts:

Pork loin is steamed, smoked and "left to rot." The first time he made it, it was "a technicolor weird thing" covered with mold. "I wondered, am I dying as I'm breathing this in?'" But when cut into, it was the same amber as katsuobushi, and just as delicious, according to Chang.

He had a hard time replicating it at first but eventually even got a scientific journal article out of documenting the process, which included having the DNA sequence of the mold analyzed.

At the end of the day, katsuobushi seems to be doing all right. People are preserving the old ways as well as changing with the times. And I'll raise a cup of miso soup to that. But not one made with granules.