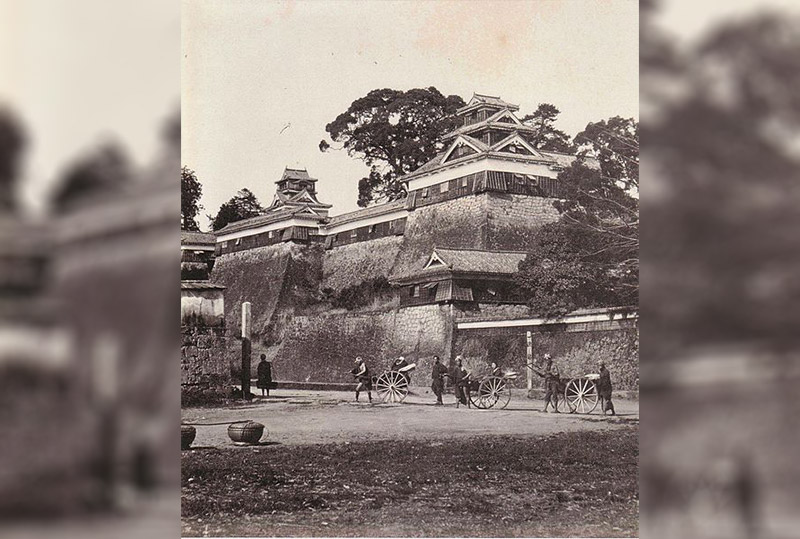

Last fall I visited Kumamoto Castle. Though mostly a reconstruction, it’s impressive nonetheless. There is currently a regular live show on the castle grounds, in which actors dressed as famous samurai stage mock fights and deliver stirring speeches to dramatic music. Chief among them was Kato Kiyomasa, lord of Kumamoto Castle. Entertaining though it was, I couldn’t help but think, “If the real Kato Kiyomasa were here, he would despise this.”

Kato Kiyomasa was an uncompromising military man. However, his family’s reign in Kumamoto only lasted two generations. They were replaced by the Hosokawa family, who ruled there throughout the remainder of the Edo period. Kato Kiyomasa and the Hosokawa lords had vastly different views on how a warrior should live, one uncompromisingly militaristic and the other a balance of war and art.

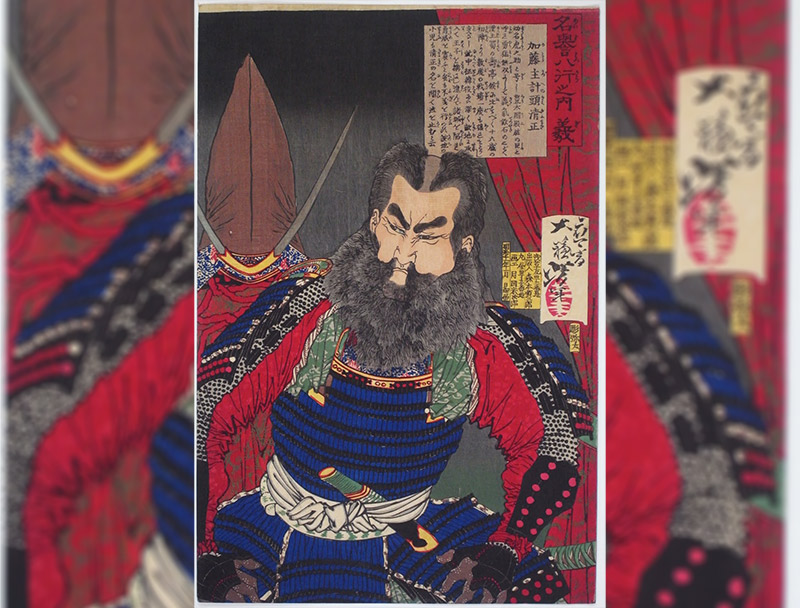

The Demon General

Let’s look at our first representative in this debate, the uber-aggressive and finely-bearded Kato Kiyomasa (1561-1611). He was the son of a blacksmith, born near Nagoya. Kiyomasa first rose to prominence thanks to his accomplishments fighting for Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the Battle of Shizugatake (1583), and became known as one of the “Seven Spears of Shizugatake.”

Kiyomasa fought in Hideyoshi’s 1586 conquest of Kyushu. Two years later, Hideyoshi awarded half of Higo Domain (including Kumamoto) to Kato Kiyomasa, and the other half to Konishi Yukinaga (1555-1600). Yukinaga was a Christian convert, while Kiyomasa was a staunch follower of Nichiren Buddhism. The two hated each other.

Kiyomasa also played a large role in Hideyoshi’s invasions of Korea (1592-1598), commanding one of two vanguard divisions. The other division of the initial invasion was led by none other than his least favorite neighbor, Konishi Yukinaga. Despite their antagonism, the invasion was quite successful at first.

The invasion later stagnated due to Korean naval campaigns and Chinese intervention. The Japanese settled in and built many forts and castles to solidify their position. Kiyomasa designed and oversaw the construction of several, skills he would later use to greatly expand Kumamoto Castle to the form we know now.

Oh, and in his down time, he hunted tigers. Yeah. Tigers.

After Hideyoshi’s death in 1598 the invasion ended, and conflict between Toyotomi and Tokugawa supporters began. Kiyomasa did not participate in the decisive Battle of Sekigahara (1600), but sided with the Tokugawa and fought Toyotomi allies in Kyushu. For his support, the victorious Tokugawa awarded him the remaining half of Higo, which Kiyomasa governed until he died of illness in 1611.

The Hosokawa

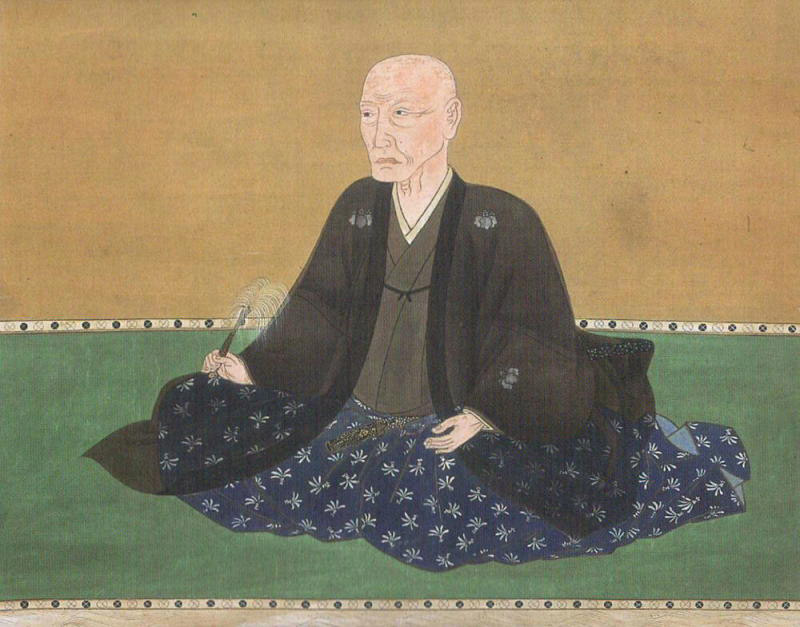

In 1632, Kato Kiyomasa’s heir Tadahiro was arrested for conspiring against the shogun and Higo was confiscated from the Kato family. It was given to Hosokawa Tadatoshi (1586-1641). In contrast to the humble beginnings of the Kato, the Hosokawa were a family with a long history of status, influence, and culture. Descended from the Minamoto, through the Ashikaga, the Hosokawa could claim the blood of two shogun families in their veins. They held many prominent positions and, over time, governed in Shikoku, Kinai, Kokura, and lastly, Kumamoto. This clan reigned in a vastly different way than Kiyomasa.

Hosokawa Tadaoki (1563-1646), fought his first battle at age fifteen and in in many campaigns thereafter, including Hideyoshi’s conquest of Kyushu. His heir, Hosokawa Tadatoshi participated in the suppression of the Shimabara Revolt (1637-38).

Way of the Warrior

Let’s broach the subject of bushido 武士道. Usually translated as the “way of the warrior,” people today generally think of it as a code of ethics followed by the samurai, kind of like chivalry among European knights. The term is hundreds of years old, but appears only rarely until the modern era. It is, for the most part, a term that people of the modern age have projected back on the past.

However, that’s not to say that some samurai didn’t have strong opinions about how a warrior should live his life. Kato Kiyomasa was one such samurai, and he wrote a set of precepts outlining his thoughts on the ideal warrior lifestyle. Since it’s a short document, I have quoted it in full. You may notice that the word bushido does appear, but since I was unable to find the original text, I am relying on William Scott Wilson’s translation. I don’t know if the word bushido actually appears in the original.

“The Precepts of Kato Kiyomasa”

ARTICLES CONCERNING WHICH ALL SAMURAI SHOULD BE RESOLVED, REGARDLESS OF RANK

One should not be negligent in the way of the retainer. One should rise at four in the morning, practice sword technique, eat one’s meal, and train with the bow, the gun, and the horse. For a well developed retainer, he should become even more so. If one should want diversions, he should make them such outdoor pastimes such as falconing, deer hunting and wrestling.

For clothing, anything between cotton and natural silk will do. A man who squanders money for clothing and brings his household finances into disorder is fit for punishment. Generally one should further himself with armor that is appropriate for his social position, sustain his retainers, and use his money for martial affairs.

When associating with one’s ordinary companions, one should limit the meeting to one guest and one host, and the meal should consist of plain brown rice. When practicing the martial arts, however, one may meet with many people.

As for the decorum at the time of a campaign, one must be mindful that he is a samurai. A person who loves beautification where it is unnecessary is fit for punishment.

The practice of Noh Drama is absolutely forbidden. When one unsheathes his sword, he has cutting a person down on his mind. Thus, as all things are born from being placed in one’s heart, a samurai who practices dancing, which is outside of the martial arts, should be ordered to commit seppuku.

One should put forth great effort in matters of learning. One should read books concerning military matters, and direct his attention exclusively to the virtues of loyalty and filial piety. Reading Chinese poetry, linked verse, and waka is forbidden. One will surely become womanized if he gives his heart knowledge of such elegant and delicate refinements. Having been born into the house of a warrior, one’s intentions should be to grasp the long and the short swords and to die

If a man does not investigate into the matter of Bushido daily, it will be difficult for him to die a brave and manly death. Thus, it is essential to engrave this business of the warrior into one’s mind well.

The above conditions should be adhered to night and day. If there is anyone who finds these conditions difficult to fulfill, he should be dismissed, an investigation should be quickly carried out, it should be signed and sealed that he was unable to mature in the Way of Manhood, and he should be driven out. To this, there is no doubt

TO ALL SAMURAI

Kato Kazuenokami Kiyomasa

Hosokawa, Rennaisance Clan

In an approach nearly the absolute opposite of Kato Kiyomasa, Hosokawa Tadaoki was accomplished not only in matters of war, but also of peace. He was a seasoned warrior, with plenty of experience on the front lines. He was well versed in the designing of castles, and responsible for some innovations in armor.

Sword mountings made by Tadaoki

He was one of the closest students of Sen no Rikyu, developer of the tea ceremony, and a tea master in his own right. He was also a poet, a painter, and a master of lacquer ware.

An eggplant shaped sake flask created by Tadaoki

After his son was given Higo Domain, Tadaoki retired there, at Yatsushiro Castle. During his retirement he commissioned the creation of the Kouda-yaki style of ceramics.

Modern kouda-yaki cup

Hosokawa Tadatoshi continued the family tradition of balancing martial and peaceful pursuits. He was an avid swordsman, proficient in the Yagyu Shinkage style. He also became well acquainted with the legendary swordsman, Miyamoto Musashi, a friendship that highlighted his balanced approached to samuraihood. The two initially met at a poetry circle in Kyoto. Musashi’s prowess in dueling and the arts interested Tadatoshi. Eventually, Musashi entered his service, and wrote The Thirty-Five Articles of the Martial Arts at his behest.

Tadatoshi also designed the Suizenji Jojū-en, a garden in Kumamoto. It was originally a tea retreat, the location chosen for its clean spring water. Much of the garden was designed to replicate the fifty-three post stations of the Tokaido, the road from Kyoto to Edo. The easiest example to spot is the mini Mt. Fuji, seen above.

The Sword? The Brush? Both?

Kato Kiyomasa and his opinions could be seen as a reflection of his time. The chaos of constant war allowed lowborn men such as him to rise in status, and his obsession with martial pursuits served him well. However, as the wars drew to an end, it was the attitudes exemplified by the Hosokawa that took hold with the warrior class during the peace of the Tokugawa era. With little fighting to be done, bureaucrats were needed more than soldiers. At the same time, samurai continued to train for battle, and dojo culture flourished. Two attitudes indicative of the Sengoku Period and Edo Period, respectively. And both housed within the mighty walls of Kumamoto Castle.