Fake eggs crossed the line. I had gone through life in Japan, blindly filling my basket at the grocery store, hunting for the best bargains instead of the healthiest or safest options. Then I heard about China’s fake (chicken) eggs – wonders of human innovation created by a complicated chemical process that look real enough to be sold and consumed by unsuspecting consumers.

Really? Artificial eggs? Chickens eat stuff off the ground and lay real eggs. Ethical issues aside, I thought factory farming had that problem solved. If any food seemed to be safe from forgery I thought the egg was it. Boy, was I wrong.

Suddenly, I found myself giving the grocery aisles a shrewd eye. The cheaper an item, the more suspect it became.

I interrogated products. “Green tea, why are you so cheap?!” Labels provided answers. “Oh, because you’re from China huh? Back to the shelf with you!”

Despite troubling trends in food safety, Japan depends on China for a surprising amount of food imports. Everyone living in Japan can stand to take caution. Yet the issue is not exclusive to Japan. China’s continuing growth as a contributor to the global food market means the issue concerns everyone.

Too Bad to Be True?

Global confidence in China’s food products has taken several blows in recent years. In 2007, when several brands of pet food made by the same manufacturer sickened and killed pets, the cause was found to be ingredients from China that were contaminated with melamine. Chicken jerky pet treats made in China have made also made thousands of pets sick and the illness has killed over a thousand dogs. The specific cause of that illness is still unknown and under investigation.

Since news of tainted pet food broke in 2007, scandals have continued to haunt China’s growing food industry. The 2008 San Lu milk scandal shocked China and the world when milk and baby formula tested positive for traces of melamine, a chemical that can cause blindness. Vaughn M. Watson of World Policy Blog reported, “By the end of 2008, China’s ministry of health reported more than 300,000 children may have been affected by the contamination.” But news of scandals only snowballed from there.

China’s food safety issues exploded into headlines earlier this year thanks to the tainted meat exported to Japan. A Shanghai company provided rancid meat to major Japanese fast food chains like McDonalds and Family Mart. Zoe Li of CNN reported on the gloveless meat handlers and forged expirations dates among the company’s illegal and unsanitary practices.

By this point nothing should come as a surprise. If food isn’t contaminated by toxins, it’s altogether counterfeit. If it isn’t counterfeit it’s rancid. At first, cases of gelatin injected shrimp, poison rice, and even glowing meat forced domestic customers to use caution. Now expired meat and poison pet foods have forced the world to take heed. When will China’s food scandals end? More importantly, why are they happening in the first place?

What Gives?

As Chinese food scandals continue to break at home and abroad, consumers are left wondering why. Experts blame pollution, lack of regulations, and the strain of providing affordable food for the world’s largest population.

Pollution

China’s air pollution may actually be more famous than its food scandals, a situation that gained notoriety thanks to the county’s quick cleanup before hosting the 2008 Olympic games. Allison Jackson of Global Post writes:

It’s hard to overstate the severity of air pollution in China. In many cities the level of contamination in the air often reaches levels considered by experts to be hazardous, and much has been said about the devastating impact it’s all having on people’s health.

But the pollution problem doesn’t end with air quality. According to state reports, sixty percent of China’s underground water is also polluted (The Guardian). The less visible, less known problem of soil contamination is nearly as bad. The Wall Street Journal reported:

One survey declassified last December had found that nearly 20% of Chinese farmland could be contaminated with deadly heavy metals such as cadmium and lead. Officials in Guangzhou last year found high cadmium levels in 44% of rice samples.

Yet pollution has done little to deter the land’s use. “In Hunan, rice production in polluted sites has not stopped” said Mr. Wu of Greenpeace.

With its most important resources to food production heavily polluted, it’s no wonder China has given birth to food quality scandals. Produce from polluted land still finds its way to the market and unlucky consumers pay the price with their health.

Regulations

If the Chinese government enforced regulations, pollution, contamination and counterfeiting wouldn’t be such a problem. Instead, the government turns a blind eye, underplaying pollution and questionable practices. The Wall Street Journal points out, “Officials classify pollution data as ‘state secrets’ to prevent the public from pressuring them to take action.”

The Chinese government is so secretive that it falls under suspicion even when it takes visible action. The overemphasis of post-scandal government “crackdowns” force many to question their validity. Conspiracy theorists believe the government set these smokescreens to reassure customer confidence and return things to normal.

Patty Lovera, Assistant Director of Food & Water Watch testified in Washington DC,

Since 2009, the Chinese government has made a point of making public displays of enforcing food safety rules, inspecting food facilities and punishing people connected with tainted food. News reports frequently reference millions of inspections of facilities and frequent “crackdowns” on particular products.

Proper inspections, performed by the Chinese government or other countries, only serve to shake consumer confidence. Stanley Lubman of China Real Time writes, “reports on the state of Chinese food processing establishments are discouraging. More than half of food processing and packaging firms on the Chinese mainland failed safety inspections in 2011, according to a report by Asia Inspection, a China-based food quality control company.”

Profit

Perhaps this is what it takes to feed the world’s largest population. But in reported cases, profit trumps necessity, regulations and well-being. Patty Lovera explains, “China’s food manufacturers often found to cut corners and substitute dangerous ingredients to boost sales.”

A Food Scandals in China timeline on timetoast.com shows meat being injected with water to boost weight, cabbages sprayed with cancerous chemicals to prolong shelf-life and the use of “gutter oil,” a low-cost cooking oil made from “reprocessed garbage and sewage” (Max Fisher). All of these practices serve one purpose – increasing profit. And that wouldn’t be a problem if it weren’t at the expense of consumer health.

The Center for Investigative Reporting‘s Rachael Bale writes, “Halting agricultural production in many of the worst-hit areas simply isn’t an option. It would put people’s livelihoods at risk and could result in food shortages.”

Enforcing food production and pollution rules with adequate inspections costs the government money. The abandonment of polluted land and disposal of contaminated goods equals net profit loss for producers. In terms of profit, enforcement creates a lose-lose situation. By turning a blind-eye everyone makes out, except consumers (and their pets).

But media exposure and the growing distrust of Chinese food producers may eventually lead to a loss of profit and food shortages anyway. For example, the 2008 milk scandal forced many Chinese to avoid domestic milk products and empty supermarkets of imported alternatives, hurting China’s domestic producers and creating shortages

Recently exposed scandals and data hurt China’s reputation and its business’s wallets. The government and businesses are slowly being forced to change. Nations that buy from China are demanding proper regulations some conduct investigations of their own. Hopefully these scandals and tragedies will lead to true reforms that force China to become a trusted food source.

Why Import From China?

Unbelievable scandals and the disregard of its own citizens’ safety begs the question – why would anyone import food from China?

Considering the countries long history of distrust and even downright hatred for one another, the question is especially poignant in Japan. But like other countries, Japan depends on Chinese imports because it cannot produce enough food to support itself.

In the past, Japan’s large population and small, mountainous landmass made providing enough food for its population a challenge. Yet farming techniques and technology helped Japan meet the challenge and for years Japan produced a large percentage of its own food.

Today Japan’s percentage of domestic food production is at an all time low. According to Kazuhito Yamashita of The Tokyo Foundation, “Japan’s food self-sufficiency ratio has dropped below 40%.” Lack of arable land is not the problem. In fact, nature has begun to reclaim abandoned plots of farmland in the country. Unused agricultural plots located in residential areas are being converted into apartments, convenience stores and solar farms. Yamashita writes, “Some 2.60 million hectares-more than 40% of the 6.09 million hectares that existed in 1961 – have disappeared due to abandonment and conversion for residential or other purposes.”

Japan’s aging farming population has also forced Japan’s dependance on imports. The country’s farmers have reached retirement age. According to one government report, in 2008 sixty percent of Japan’s farming population was sixty-five years old or older (maff.go.jp), and no one is replacing the void left by these retirees. Most young people have no desire to live in the country or farm for a living. They perceive the farming lifestyle as uncool, inconvenient and therefore undesirable. Current population trends show Japanese citizens are migrating to cities. The Japan Times reports,

The three largest metropolitan areas around Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka combined had a record high population of 64.39 million as of January, accounting for 50.9 percent of the whole nation, while 39 of Japan’s 47 prefectures lost population compared to the previous year.

Thanks to government subsidies Japan still produces enough rice for its population. But that’s not true of all Japanese food staples. Kazuaki Nagata of the Japan Times explains,

Although Japan’s self-sufficiency rate for rice, eggs, whale meat and mandarin oranges exceeds 90 percent, the rate for essential ingredients for Japanese cuisine, including soy beans, is a mere 5 percent, and just 13 percent for daily necessities like cooking oil. Half of the meat products consumed in Japan is imported.

Japan isn’t alone – countries around the world are growing dependent on Chinese imports. Patty Lovera, Assistant Director of Food & Water Watch testified in Washington DC on behalf of the American people,

China is the largest agricultural economy in the world and one of the biggest agricultural exporters. It is the world’s leading producer of many foods… apples, tomatoes, peaches, potatoes, garlic, sweet potatoes, pears, peas – the list goes on and on.

Like Japanese and Chinese citizens, Lovera worries about the dangers of Chinese products and advocates stricter enforcement of import regulations at home to make up for the lack in China. As China grows as a global food producer, we all have reason to use caution.

Major Chinese Imports

After learning to read Japan’s food labels, I found the amount of food imported from China surprising. And there was usually one dead giveaway – the lower the price of the product, the more likely it originated in China. Most of my local supermarkets’ honey and peanuts came from China. Honey from other countries sold for about five times the price. Non-Chinese peanuts went for triple the cost.

Deeper investigation revealed the majority of Japan’s garlic, pumpkin seeds and frozen berries also come from China. China’s garlic is so cheap that it undersells locally grown garlic, despite shipping costs. In America, cheap garlic imports are putting California’s local garlic growers out of business. As China increases its production of green tea and kimchi, local Japanese and Korean industries might face the same threat.

Now I don’t want to seem unfair. All countries have their share of contaminated food products. Japan has strict regulations on American beef imports due to mad cow disease. Germany and Scandinavian countries lead the world in incidents of campylobacter, salmonella, yersinia, e.coli and listeria. Perhaps some degree of contamination comes with the food business. But out of all the world’s food scandals, China’s are the most consistent, bizarre, and alarming. And research shows we have reason to worry.

What You Can Do?

Although strict regulations and enforcement would be optimal, they are not a reality. Right now we have to take responsibility for ourselves. Since China has become a global food provider, anyone that cares about their health needs to remain vigilant.

But taking extra care can prove tricky abroad, where language and cultural barriers add a layer of difficulty. Throw in three different types of characters (hiragana, katakana and kanji) and it becomes downright intimidating. That’s why Tofugu is providing these tips and tricks to help our fans in Japan protect themselves.

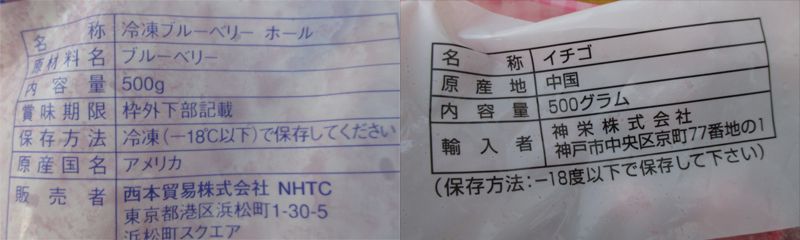

Most packaged foods feature important product information on the back of the package, framed by a convenient little table. Here are the categories that usually fill out the table’s left side.

| Japanese | English |

|---|---|

| 名称 | the product’s name |

| 原料, 材料 | ingredients |

| 原料原産地名 | the goods’ or ingredient’s place of origin. |

The following locations are featured on the right:

| Japanese | English |

|---|---|

| 国産 | domestic |

| 県 | prefecture |

| 中国 | China |

| 韓国 | Korea |

| アメリカ, 米国 | America/United States |

| カナダ | Canada |

| 保存方法 | storage instructions |

| 商品の 情報 | product information |

| 内容料 | the content quantity/weight of the goods/package |

| メーカー 名 | name of maker/manufacturer |

| 製造者 | manufacturer |

Overwhelming labels become less intimidating when you know what to look for. The most important kanji to remember are genryou gensan chimei 原料 原産 地名, kokusan 国産, ken 県 and if you intend on avoiding Chinese products, chuugoku 中国.

From the examples above we can see that the package on the right contains strawberries (イチゴ) from China chuugoku 中国. That label lists little information and is easy to decipher. The one on the left contains more detailed information. But when you know what to look for, finding the important information becomes easy. It contains blueberries (ブルーベリー) from the United States (アメリカ).

Happy label reading!

The Label-less

While produce like loose vegetables and fruit don’t have labels, they often have signs nearby explaining their origins. In the case of imports, the signs will show the country of origin. This is where knowing the kanji for China comes in handy.

In the case of domestic produce, the sign will display the prefecture’s name. Remember, prefecture/ken is written with ken 県. So if the sign shows a bunch of kanji with ken 県 at the end, the item is probably domestic, from one of Japan’s prefectures.

Research Online

If a food seems suspicious, for example it has an unbelievably low price or a strange taste, search for it online. I didn’t know Japan imported green tea from China until I bought a cheap, odd tasting green. The package revealed that it came from China and this article from Greenpeace informed me that Chinese tea leaves test positive for banned pesticides. From then on I made sure to buy domestic green tea.

When I searched for Chinese honey, I discovered that the United States bans the product due to illegal antibiotics and heavy metals. Cassandra Profita of Oregon Public Broadcasting reports, “Chinese honey producers inject some honey with water, heat it, filter it and distill it into syrup, which wipes out antibiotics but turns it into a diluted, less valuable product that can be sold below the price of regular honey production.” The enterprise is so profitable it has given birth to global Chinese honey smuggling rings.

A search for cheap garlic revealed that Chinese garlic had “high levels of lead, arsenic and added sulfites” (The Washington Post). The trend continued and my searches exposed antifreeze contaminated toothpastes, “catfish laden with banned antibiotics, mushrooms laced with illegal pesticides, and others” (The Washington Post).

When you’re uncertain about the quality of a product from any country, do an internet search. What it reveals might surprise you and change your shopping habits!

You Are What You Eat

In the past, I shopped for the best deals. Price dictated what I bought and quantity ruled the day. But when getting more for your money includes extra antibiotics, heavy metals, molds, and pesticides it may be time to change your shopping habits. Watching your budget is important, but so is protecting your health.

China’s recurring food scandals should have us all taking extra caution. Although news of China’s tainted dog treats first broke in 2007, instances of sickness and deaths from those treats continue today. It’s unfortunate, but these instances can be avoided. Small efforts, like checking labels and doing a little research can go a long way.

Although I’ve become cautious, there are always new surprises. Thanks to this article I learned my frozen strawberries come from China! Time to do more research!

Of course, even with extreme caution, you can never be too sure. The idea of honey smuggling seems like a joke, but it’s a real problem. Though the label may say pure honey from India, customers might actually be buying watered down, contaminated honey smuggled from China.

Each new China food scandal makes the next one easier to swallow (pun intended). Instead of shock, we’re left wondering, “what’s next?”

From gutter oil to fake eggs and poison milk, nothing about the bizarre state of Chinese food production surprises me anymore. But with a little effort I hope to avoid becoming a victim of food scandal – it’s bad enough having to read about them.