For most of us who get the chance to handle a finely crafted nihonto 日本刀 Japanese sword, we couldn't do much more than hold it cross-eyed and bleat out "nice sword." Why some consider a Masamune on par with a da Vinci eludes us. Japanese swords are works of art, but to the untrained eye one isn't much different from another. While being able to properly appraise a sword can take a lifetime, fortunately, you can see what makes a sword unique just by knowing what to look for.

Nihonto or Gunto?

Gunto 軍刀 (meaning either "saber" or "service sword") were the swords of Japanese WWII officers. Although some gunto were either handcrafted or partially handcrafted, most were assembled in factories from standard bar stock. Telling a gunto from a high quality blade is usually easy. If you can read Japanese and know how to open the grip, the signature on the tang (the part of the blade inside the handle) will tell you exactly what it is. If you can't do these things, it's still not very difficult.

If the sword is in Japan it is definitely a nihonto. Since the mass-produced gunto have no artistic value, the Japanese government classifies them as weapons. Owning one is illegal in Japan. There have been cases of American gunto owners wanting to reunite a Japanese soldier's sword with his family, but unfortunately the law makes that almost impossible. If you try to bring a gunto into the country, it will be confiscated and you will be deported as if you tried bringing in an AK-47.

If you're not in Japan, though, one way to tell is the scabbard. Gunto are actually not based on katana, but an older kind of sword called a tachi. Tachi look pretty similar to katana, but were worn horizontally, edge-down behind a samurai's back. Japanese WWII soldiers hung their swords at their hips, but edge-down from loops on the scabbard. So if the scabbard has hangers, it is probably a gunto. The cheapest gunto also have serial numbers on the blade, which immediately tells you they were mass produced.

Still, some WWII swords were family swords modified for military fittings. You would normally be able to tell them apart from the steel's grain or the temper line, but unfortunately, most swords that made their way abroad are in such poor condition the metal's features have faded. The only way to tell is the signature, which most people can't read. It's really too bad, because somewhere out there is a Japanese national treasure called the Honjo Masamune, which was taken by a G.I. and never recovered.

The Basics of Shape

Now that you know if it's a nihonto or gunto, next is viewing the blade's personality. Japanese swords have a lot of details that are hard to catch without proper lighting, so you need a good, strong light source.

It's traditional to bow to a sword before a viewing, though if the occasion is informal it'll probably look strange. First, hold it edge-up and push the hilt away from the scabbard with your thumb. Do not touch the metal. The acid in your fingerprint will cause rust. Slide the sword out along its back to make sure the scabbard doesn't scratch the blade.

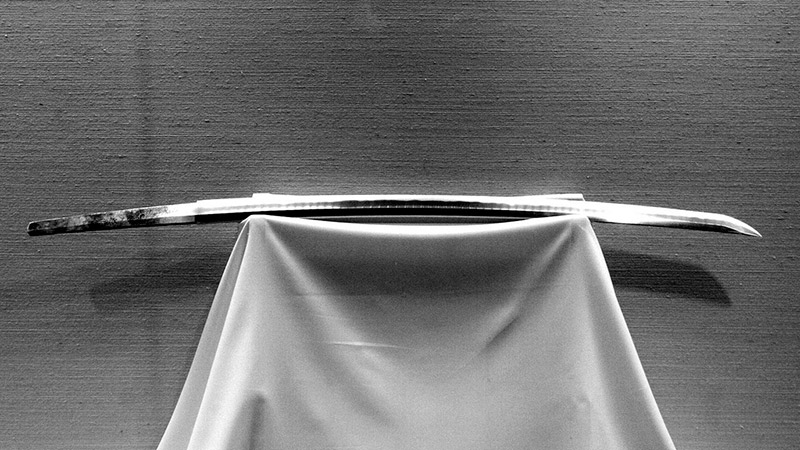

Once out, hold the sword upright at arm's length and notice the curvature. For ancient blades, the placement of the curve affected its cutting power and how quickly it could be drawn. The point determined its piercing power, and could vary from long and curved to short and angular. The smith would also choose which kind of back to forge, from flat to three-sided. Appraisers would use all these features to tell which period and school of swordsmithing the sword came from, but if you're just viewing a blade, it's enough just to know these features exist.

The Basics of Steel

Nihonto are usually made from a high-carbon steel called "tamahagane 玉鋼." Carbon makes steel hard, but it also makes it brittle. Tamahagane has so much carbon that a sword made from the untreated metal would shatter the first time it was used. There's a common belief that a Japanese sword's strength comes from folding it, but folding actually makes tamahagane softer, not harder. Each fold brings down the carbon content about .2 percent until it's soft enough to withstand being used.

Below is a great example of the steel folding process.

The common image of a katana being folded thousands of times depends on what you consider a fold. If you count the actual amount of times the smith folds the steel, folding it a thousand times would drop the carbon content to zero, making the steel unfit for a sword. If you count the number of layers actually created in the metal, though, the number of "folds" grows exponentially. Either way, layering forms a distinctive pattern that appears after polishing. Waves, knots, and even wood-like patterns can be created depending on how the smith folds the billet. To view the grain, place a light above and behind you, then hold the blade horizontally.

Although tamahagane is crucial for making Japanese swords, it was almost lost to modern science. The steel is made in a smelter called a tatara, all of which ceased operations in 1945. Fortunately, in 1975 a society formed to preserve interest in nihonto and managed to revive tatara operations in Shimane prefecture. Smiths occasionally make their own metal, but most of Japan's tamahagane is still being made by that very same tatara.

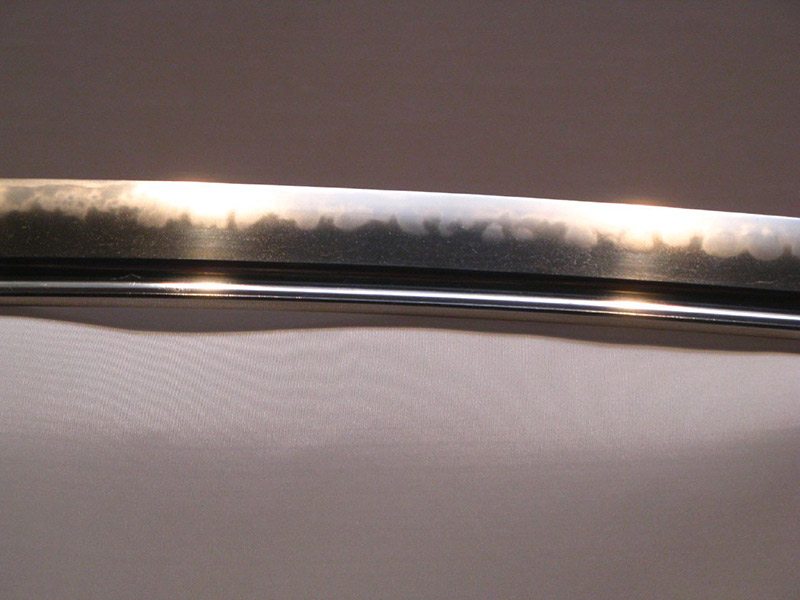

The Basics of the Temper Line

In the picture above you can clearly see the wavy line where the side of the steel near the edge is lighter than towards the rear. It's called the hamon 刃文or temper line, and it's a Japanese sword's most distinct feature. In manufactured swords it's nothing more than a decoration, but the hamon of crafted swords is part of why katana are some of the best swords in the world. Japanese swords are forged from at least two steels. The rear of the sword is soft steel that acts as a shock absorber, while the edge is made of harder steel for cutting.

Before quenching (when the red hot blade is suddenly submerged in water) smiths coat it with a clay mixture to cool the edge slightly faster than the back. The difference is only a few thousandths of a second, but it turns the edge into an even harder kind of steel called martensite. It also creates the hamon. In ancient times, its main function was to create a powerful blade. Today, it's an opportunity for the smith to express himself artistically.

Examine the hamon by pointing the sword just below your light source with the edge up. Moving it continuously should reveal a thin white line along the boundary between the steels. If the sword was well-made, you'll also see any number of hataraki 働き or special features within it, like cloudy patterns or "feet" that extend towards the edge. A lot of swords on the internet sport fake hamons, which, like gunto, probably won't have any hataraki or patterns within the grain.

Smiths sometimes gamble with the hamon. At times they don't use clay, but heat the edge and rear of the blade at different rates to create a natural pattern. A smith using this method has no control over the hamon's appearance, but the natural quenching could create distinctive and beautiful patterns impossible with clay. While this can create stunning hamon, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Many nihonto admirers prefer to appreciate the smith's hand in creating a distinctive hamon rather than one at random. Appearance is important, but hard work and effort is appreciated even more. A beautiful hamon made without clay is merely a matter of luck, after all, and not skill.

Bells and Whistles

Making a blade takes months, but a sword takes even longer. The smith does a rough grinding and polishing after he finishes a blade, but then it's sent to a professional sword polisher. The polisher uses a series of increasingly finer stones to bring out the steel's details. Without a skilled polisher, the blade would just look like a featureless piece of metal.

Many collectors only care about the blade itself, so many new swords are only sheathed in a shirasa, a simple wooden scabbard. However, if the smith wants all the bells and whistles, he will send his creation to a scabbard maker. He might then himself make the tsuba 鐔(guard), habiki はばき (the small metal piece that fits the sword into the scabbard), and any engraving, or he can send it to individual specialists for each. Whether by the smith or another craftsman, each part of a Japanese sword has a lot of effort put into it, so take a moment to examine them in turn before you finish your viewing.

Viewing a Japanese Sword

Even if you can't tell a Bizen from a Soshu blade, you can still look at a Japanese sword and understand what you're seeing. It's a lot like admiring the brushwork of a Van Gogh. Before you realize it's there, you can only see the picture. But once you do, you can see the master's hand at work.