Hearing someone say "pottery!" might not inspire quite the same degree of excitement as "new Nintendo system!" or "free beer!". But before you leave this page in search of Nintendo and/or beer related articles, why not give pottery a chance? It's actually a pretty fascinating subject, what with all the possibilities of shape, texture, and colour, and with examples surviving all the way back to the stone age.

No country features a more profound, widespread appreciation for the art of pottery than Japan. This is due primarily to the tea ceremony, a core component of Japanese identity. The implements of this ceremony are accorded high aesthetic status; so if you happen to be a teacup, Japan is the place to be. Teacups are like rock stars there, man.

Why Pottery Rocks

Broadly speaking, pottery (aka ceramics) denotes anything made of baked clay. One of humanity's earliest and most crucial inventions, pottery allowed settled societies to store food and water, and it sure made eating and drinking a lot less messy.

Works of pottery are often one of the chief surviving physical remnants of historic cultures. And since pottery is often painted and/or sculpted, it gives us a glimpse into the aesthetic values of long-vanished peoples. All around the world, wherever settled life developed, ceramic shards have been excavated…fragments of ancient imaginations.

Pottery survives in abundance because it's just so darn durable. Though easily broken, pottery shards are highly resistant to disintegration, allowing modern archaeologists to put humpty together again. Painted designs upon pottery surfaces are also quite resilient, provided they were added before the baking process.

It's kind of ironic that pottery, with its inherent delicacy, turns out to be among the most ruggedly enduring of human creations. Remember the fable about the oak tree and the reed? The mighty oak was blown over by a strong wind, while the seemingly fragile reed simply bent and weathered the storm. So it is with pottery, which endures the centuries in shard form, while murals and statues crumble away.

Baby, You so Fine

A fundamental distinction may be drawn between "fine art", the creation of purely aesthetic works, and "applied art", the crafting of aesthetically pleasing practical objects. Today, society widely recognizes the importance of both for quality of life. In addition to movies and TV shows (two principal contemporary forms of fine art), our modern society yearns for well-designed cars, appliances, and websites (especially this one). So it was for historic societies; only instead of coding html, they made clay pots.

Are you convinced that pottery is cool yet? I don't see how you couldn't be, given that I just compared it to a computer language. So now that you're all ceram-excited (sorry[P.S. I'm not sorry]), it's time to look at pottery styles throughout Japanese history. Don't worry, I'm not going to torture you with thirty-seven distinct stylistic periods. I'm going to torture you with four.

It's Early Days Yet

While Japanese ceramics now stand among the world's most famous and celebrated traditions, they took a while to find their voice. The classic, iconic Japanese pottery style (known as "wabi-sabi"; more on that later) wouldn't mature until the beginning of the shogunate period (ca. 1200-1870). Thus, all the millennia leading up to this development may be grouped as a vast "early period".

The oldest Japanese pottery of all is that of the hunter-gatherer Jōmon culture, which inhabited Japan ca. 10,500-300 BC. The name "Jōmon", meaning "cord-patterned", is derived from this culture's fondness for decorating pottery with patterns of lines (by pressing cords into the wet clay). This was probably done, at least originally, to imitate the textures of woven baskets.

The centuries following the Jōmon period witnessed the rise of agriculture (rice cultivation), metal casting (first bronze, then iron), and eventually a unified Japanese civilization. Technological advances arrived from China, often via Korea.Throughout history, young civilizations have generally been heavily influenced by elder neighbours; after all, why reinvent the wheel (or the kanji)? Japan's story is a typical one, progressing from an "absorption phase" of heavy external influence to an "independent phase", in which borrowed elements are adapted to indigenous culture. The magnitude of Chinese and Korean influence is readily observed in Japanese pottery, which resembles mainland styles for many centuries.

Want some proof? Check out these three works from China…

…and these three from pre-shogunate Japan.

The most renowned cultural period of pre-shogunate Japan is the Heian age (ca. 800-1200), during which mainland influence peaked, then finally began to ebb. Meanwhile, the rise of independent, distinctively Japanese forms of art began en masse. Pottery's golden age gleamed on the horizon.

Classic Cool

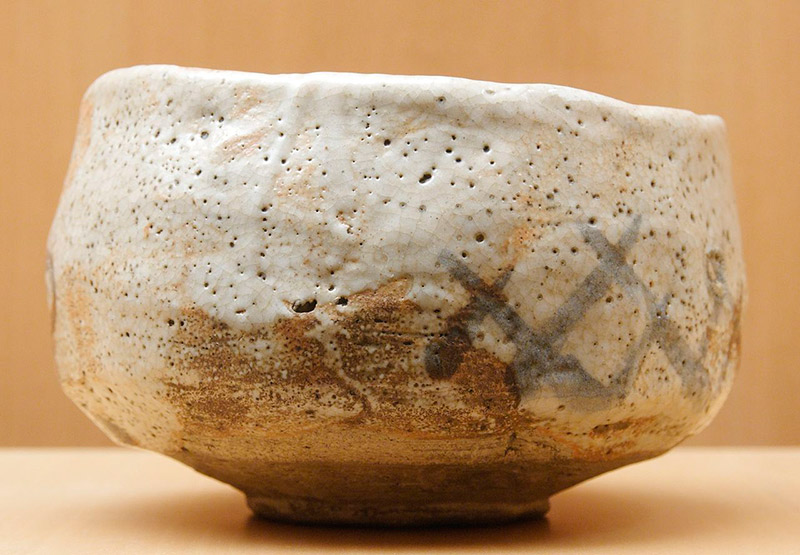

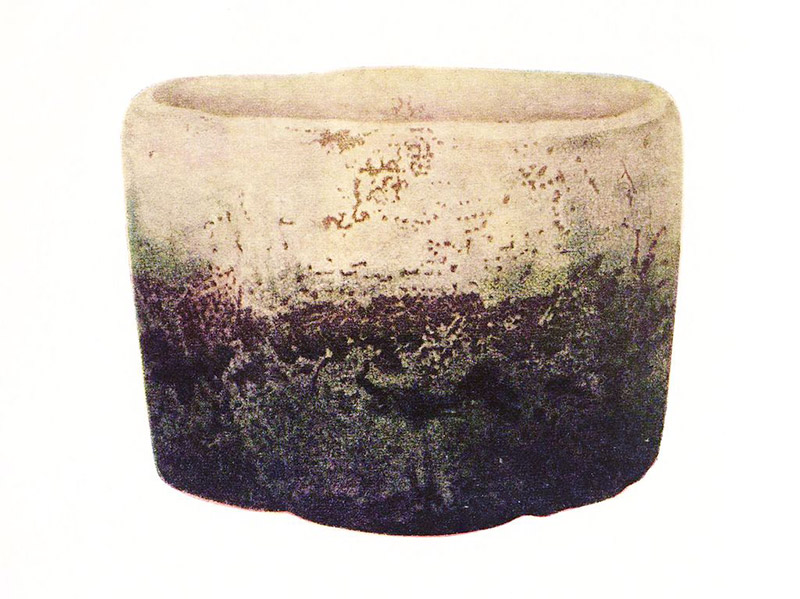

Classic Japanese ceramics, which matured and flowered in the early shogunate period, are guided by the aesthetic of "wabi-sabi". This approach, which reflects the ideals of Zen Buddhism, embraces simplicity, naturalness, aging, and irregularity. The centrality of wabi-sabi to traditional Japanese art has been described as equivalent to that of Greek classicism in the West.

So what does this mean for pottery? We're talking plain, irregular shapes. We're talking cracks, burns, and pits. We're talking haphazard arrangements of colours.

These effects were achieved with several techniques. Vessels were moulded manually, instead of being precisely shaped on a potter's wheel. Baking was conducted at relatively low temperatures, thereby avoiding the glassy, polished look of high-temperature ceramics. Instead of being allowed to cool gradually, hot vessels were removed from the kiln and plunged into straw or water, causing such effects as warping, crackles, and distorted colours.

The final product, shaped by natural processes rather than precise human guidance, is the embodiment of wabi-sabi.

The golden age of Japanese pottery is often dated to the sixteenth century, when the Japanese tea ceremony really took off. The primary figure in the rise and refinement of this ceremony, Sen Rikyū, was pivotal in the establishment of the wabi-sabi aesthetic. Rikyū oversaw the development of "raku ware" tea bowls, which are often considered the pinnacle of classic Japanese ceramics.

The two photos below, as well as the two above, are all examples of raku ware. (And so is the photo in the introduction…I just couldn't get enough!)

Wabi-sabi vessels were originally restricted to a "natural look", in which textures and colours were left to develop on their own. Eventually, some wabi-sabi artists experimented with altering these effects through manual intervention, resulting in a sort of "controlled natural look". Some artists went even further, adding painted designs.

Pretty Colours

After centuries of simplicity and restraint, who could blame potters for wanting to splash some colour around? This was the central focus of pottery during the Edo period (17th-19th c). Smooth, precisely shaped vessels were painted in crisp, vibrant designs, often on a white background. This sort of pottery became technically possible with the adoption of advanced kiln technology from Korea.

Mind you, the rugged wabi-sabi style certainly didn't disappear. It just simmered on the back burner while artists revelled in the glassy, brightly painted ceramic styles that the mainlanders had hogged for so long. A couple of wabi-sabi-ish ceramics from the Edo period are featured here.

Back to Basics

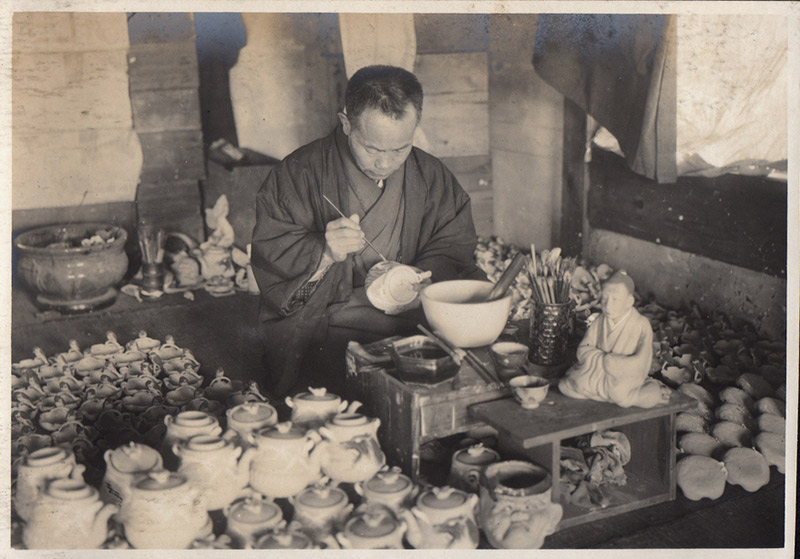

Modern Japanese ceramics, like modern art around the world, comes in a dizzying variety of styles, both old and new. Yet the most consistent thread has been revival of the classic wabi-sabi tradition. The central figure of this revival was Yanagi Sōetsu, an early twentieth-century artist who championed the simple ceramics found in typical Japanese homes.

The photo above of the interior of Sōetsu's house, provides a glimpse into his aesthetic philosophy.

Naturally, the fancier side of Japanese pottery also continued to flourish in the modern period. Kitaōji Rosanjin, also of the early twentieth century, may be the most famous name in this area. Here we see a highly-decorated Rosanjin bowl.

Cooldown Time

So, was I right? Did you find pottery to be a fascinating subject? (If not, at least be Japanese-polite and pretend you did.)

In Japan, the art of pottery achieved exceptional heights. In a land of sublime scroll paintings and transcendent haiku, one might not expect simple functional objects to have received such loving attention. And yet they did.

The respect accorded to the humble tea bowl reflects a profoundly enlightened outlook. Life is so much hoopy-er when we take the time to appreciate all forms of beauty, and to pour them into every part of our lives. Even the part when we are just sitting quietly, sipping tea.