If you wander the streets of Japan looking for mythical creatures, sooner or later you’ll bump into one–well, at least a statue of one. Stone kitsune stand guard at thousands of Inari shrines and ceramic tanuki figurines grin on shelves nationwide. But why is there such a depressing lack of real, live specimens? Where have all the nine-tailed kitsune gone? Whatever happened to all those tanuki with scrota more versatile than a Swiss army knife?

Even though it might seem futile, don’t give up the hunt! There are living Japanese legends to be found if you just know where and how to look. While you might be hard-pressed to encounter a flesh-and-blood tengu or kappa on your travels, consider this your field guide to a few of the legendary creatures known to currently exist in Japan.

Kirin 麒麟

The Legend: Long before debuting as a beer mascot, kirin referred to a fantastic creature Japan imported from China, known as a qilin in Chinese and often misleadingly translated as a “Chinese unicorn.” While depicted in a variety of ways over the centuries, the kirin generally sported a horn on its head, a multicolored coat with a yellow stomach, a horse’s hooves, a deer’s body, and an ox’s tail. Known for its laid back demeanor, when the kirin wasn’t signaling the appearance of a wise sage or benevolent ruler, he could most often be found munching grass and other vegetarian foodstuffs.

The Living Legend: During the early 15th century in China, a man named Zheng He returned from an overseas voyage to Africa and presented a kirin to the reigning emperor. A contemporary drawing of the specimen can be viewed below:

If it looks a lot like a giraffe to you, that’s because it is. But to Chinese eyes, this never-before-seen creature unmistakably resembled their legendary accounts of the qilin–a deer’s body, an ox’s tail, a horse’s hooves, a multicolored coat with a yellow stomach, and hey, even horns(-ish)! This case of mistaken identity has been immortalized in the Japanese (and Korean) language: kirin is still the word for giraffe today.

Where to Find One: There are two basic options here. You can attempt to achieve sagehood in the hopes that a kirin will grace you with its presence, or you can conserve your wisdom and go to one of a handful of zoos in Japan to see a kirin up close and personal. Ueno Zoo in Tokyo is a solid choice, although Kushiro Zoo in Hokkaido is now home to a baby kirin.

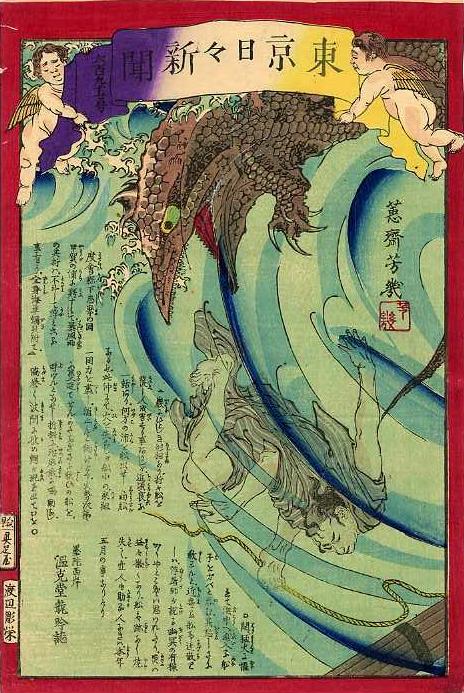

Wani 鰐

The Legend: The wani (not yet combined with a kani) is an amphibious and ambiguous sea monster that first made a splash in Japan’s oldest existing written work–the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters; early 8th century). According to this myth, the daughter of the Sea-Dragon Deity transformed into a wani when she caught her husband creeping on her while she was trying to give birth to their son (AWKWARD). Whether it appears to be dragon-like, serpent-like, or shark/fish-like, the wani is invariably depicted as loaded with scales and teeth.

The Living Legend: While the original sea monster wani has yet to be discovered, in a process similar to that of the kirin, wani eventually came to refer to crocodiles/alligators. Like the giraffe, the crocodile is another species not indigenous to Japan that just so happened to be the spitting image of a previously conceived mythical creature (or close enough, anyway).

Where to Find One: Your best bet is to swing on over to the wani exhibit at Tokyo Zoo after you’ve finished investigating the kirin there.

Dokyo osamushi (ドウキョウオサムシ)

The Legend: The 8th century Buddhist monk-turned-politician Dokyo was well-known for a number of reasons: his rise to power thanks to the patronage of Empress Koken, his reputed love affair with said Empress, his attempt to usurp the throne, his exile by the rest of the court…and his genitalia of legendary proportions. At quite possibly the most X-rated show-and-tell in world history, Prince Shotoku and Dokyo supposedly went head to head in a “phallic contest” to determine who could better “serve” Empress Koken. Presumably after refastening his robe, Dokyo was declared victorious.

The Living Legend: Even though Dokyo and his dong have long since passed on, the legend survives in the beetle sub-species named after him: Dokyo osamushi, or the Dokyo ground beetle. What do a power-hungry monk and a ground beetle have in common? Well, apparently they’re both extremely well-endowed. The Dokyo osamushi’s endophallus (I’m sure you can guess what that is) is 1/3rd the length of its entire body.

Where to Find One: Fittingly, the Dokyo osamushi struts its stuff where Dokyo himself used to strut his–Nara prefecture, the seat of the Japanese imperial government during Dokyo’s lifetime. Keep your eyes on the ground and check under rocks–especially if you decide to hike up Kongou Mountain (金剛山), a particularly popular spot for these critters to hang out. You might even catch an impromptu “phallic contest.”

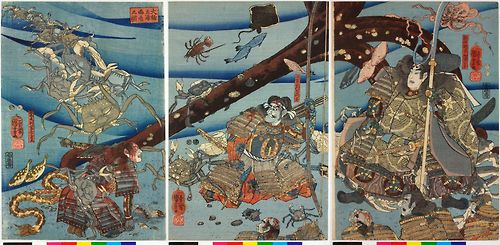

Heike-gani 平家蟹

A rendering of the fall of the Heike by ukiyo-e (‘floating world’) artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

The Legend: During the Genpei War of 1180-1185, the Taira (also known as the Heike) and the Minamoto (also known as the Genji) clans duked it out for control of Japan. In the decisive sea battle at Dan-no-ura, the Minamoto destroyed Taira resistance once and for all. In addition to the Taira casualties slain at the enemy’s hand, many of the clan chose to commit suicide once the outcome of the battle became apparent, including the boy Emperor Antoku and his grandmother. What became of all those angry samurai tossed into a watery grave?

The Living Legend: Look no further than the Heike-gani. With shell patterns disturbingly reminiscent of vengeful Taira/Heike warriors, it’s no wonder the locals thought of them as the reincarnated spirits of the fallen, consequently coining the term Heike-gani, or Heike crab.

Where to Find One: If you’re the adventurous type, you could go hunting for them yourself in their natural habitat–Japan’s Inland Sea. But if you’d rather stay on dry land, keep an eye out for a display at markets around the shore line. And if you’re willing to “shell out” roughly $8 US dollars, you can even buy your very own samurai ghost crab.

The Hunt Continues

From the kirin to the heike-gani, these legendary creatures are living history–literally and figuratively. While not legendary creatures in the sense that they possess supernatural powers, they are legendary creatures in the sense that their names and appearances physically embody legends. They’re real, live evidence of the interdependence between culture and language–not to mention proof that penis jokes are timeless.

But I’m sure there’s a lot more where that came from. What did I miss? What are some other interesting combinations of Japan’s history and Japanese etymology?

Happy hunting!