The New Year is bright and shiny and new and you’re probably thinking about your resolution to study more kanji, while Halloween is far in the rear-view mirror. Well, I’m firmly of the belief that Halloween should be celebrated year-round with some good old-fashioned horror stories, so let’s dive into another discussion of horror fiction in Japan. In the first installment of this series, we talked about the narrative skeleton of Japanese folktales and how these origins influenced the plot structure of Japanese horror. Well now it’s time to put some meat on those bones and talk about some of the emotional themes of Japanese horror tales.

Emotion and Horror

When asked about the need for horror films, David Cronenberg, in defense of his craft, once said,

For me horror films are films of confrontation, in a horror film [you] confront things that you really might not want to cope with in your real life, in a kind of safe dreamlike way. But you will meet these things eventually.

Horror fiction aims to allow the audience to confront things that they know are part of life, but are hoping to not have to face for as long as possible. Things like death, separation, deformity, madness, and disease. Many of these act as the antagonist in horror fiction, not in the same way as, say, Freddy Krueger, but because they represent the nameless, faceless, and quite painful realities of life that most people try to push out of their minds.

Horror fiction makes you face these things in relation to the strong emotions that they convey, and this is especially true in Japanese horror fiction where emotion and atmosphere are central to the storytelling experience. In this article, let’s look at some of the primary emotions Japanese horror explores and how they contribute to its distinctive sense of–

Fear

Okay, what is it that Yoda said about the path to the dark side? Anger leading to hate and hate leading somewhere and then something else? Oh, whatever, the point here is that, for the purposes of this article, fear is the dark side of the Force—because everything leads to fear. Pure primal fear is the emotion that horror fiction is trying to elicit from its audience and all of the other emotions we’re going to discuss are a means to that end.

Fear is typically defined as “an unpleasant emotion caused by the belief that someone or something is dangerous, likely to cause pain, or a threat.” In horror fiction, the fear typically comes in two different flavors: slow-moving disorienting creepiness, and in-your-face fight-or-flight fright (say that five times fast). The former is like seeing a shadowy figure in the distance that disappears after you briefly turn away. You have no way of assessing if this is in fact a threat, but it puts you ill at ease anyway. What’s more, the fact that you don’t know if a stimulus is a threat makes you even more uneasy than if you just knew in the first place. The latter type of fear is more obvious. You know just what you are in for and it ain’t good, like having a chainsaw-wielding maniac run you down in a–

Rage

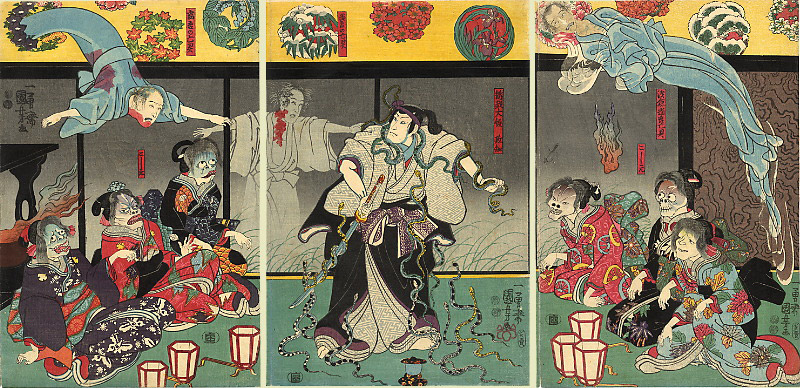

Rage is an important component in the Japanese horror story as it is often a powerful vehicle for the plot. Rage is either treated as a very problematic character flaw that sets dark events into motion, or as a force so powerful and binding that it causes the spirits of the dead to linger on earth to carry about their revenge—sometimes both in the same story.

In “Ju-On: the Grudge” for example, Takeo Sayeki murders his wife Kayako, son Toshio, and cat Maru in a fit of jealous Rage after discovering Kayako’s love for another man. The indignant rage Kayako feels at her family’s brutal murder coalesces into a curse that binds their souls to this earth as vengeful ghosts.

Rage in the case of the jealous husband character is a used as a device that causes deviation from normalcy. Japan is often a very traditionalist country that values things being in routine to create harmony. Anything that deviates from the routine is represented in folklore to be a negative change and worthy of scorn. In this case, rage is used as a mechanism for a heinous crime to be enacted. In essence, it is a cautionary tale towards temperance and controlled emotion in order to avoid disastrous results. Very Buddhist.

As for Kayako, her rage is shown as both her tether to the world of the living and as the seed of a powerfully destructive curse. This makes her an onryō, a type of vengeful Japanese ghost whose origins date back to the 8th century. Again, it is a cautionary tale to:

- Treat others nicely and coexist in society—you don’t know what they’re capable of.

- Keep your emotions in check because there is nothing but chaos to be wrought.

Rage scares us as humans because it is the emotion that is the most likely to be violent or destructive. It’s also possible to be so blinded by rage that people can find themselves doing things that they wouldn’t otherwise do. Powerful emotions like this form the basis of horror because not only do they make villains scary, but they can also make you scary to yourself, leading to regret and–

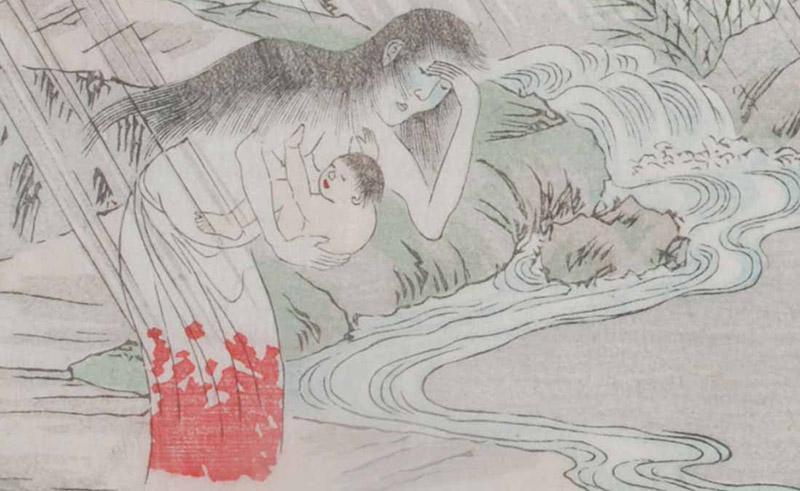

Sorrow

Sorrow has a similar role to rage in Japanese horror with quite a few Japanese ghosts being born of extreme sadness and not explicitly rage—such as the ubume. Ubume are ghosts of women who died during childbirth and they return sorrowfully either chanting that they wish they could give birth to their baby, or else swaddling a rock or jizo statue in effigy of the child they never got to hold. That is at least twenty kinds of sad.

Sorrow is employed in contemporary horror very similarly, having bad things happen to good people makes an audience sympathetic and loosens them up to be unsettled. Like the ubume, much of the sorrow in horror comes from characters with powerful feelings of–

Love

When thinking about the components of horror fiction, love probably doesn’t immediately come to mind—but it should. The feeling of love is another powerful emotion that instigates a lot of the events in horror and embodies most of its impact. Back to the first example, if Kayako didn’t fall in love (or at least appear to) with another man then the events likely would have been avoided. Similarly, if Takeo hadn’t been madly in love with his wife (albeit to a controlling and creepy extent) he never would have committed his awful crime.

For the audience, love is primarily the lens through which we interpret our connection with the characters. If a slasher murders a random victim, it’s perhaps scary or off-putting, but it’s different if a slasher murders their spouse. Now there’s intrigue. Now there’s emotion. Not only that, but it gets us thinking about our own loved ones. Would they ever do this to us? Hopefully not, but that is a scary thought.

In Japan, the exploration of love as a motivator for scares dates as far back as the onryō, many of them found themselves in their incorporeal predicament because of love one way or another. In the 17th century one of the most popular tales of eerie affection came to light. In the story of “Botan Dōrō,” a widowed samurai falls for a woman who walks by his house at nights holding a peony lantern. They meet often (she visits at dusk and must leave before dawn—typically that’s a red flag) and promise themselves to one another. The samurai’s neighbor becomes suspicious and sneaks in at night to check on him. She finds him sleeping with a skeleton. For his own protection, the neighbor locks him in the house and places a warding charm to prevent the ghost from gaining access. His ethereal lover is no longer able to enter, but she calls to him from outside. Eventually, the samurai decides that he loves the ghost too much to resist and leaves to be with her. The two lovers retire to the woman’s abode, a temple grave. The next morning the samurai’s dead body is found there embracing the woman’s skeleton.

For more modern explorations of love in Japanese horror fiction, turn your attention to who else but the horror manga godfather, Junji Ito. The film “Love Ghost,” based on one of his manga works, explores many of the ways that love can interact with, despite horrifying scenarios. His multi-part manga and movie series about an evil entity known as Tomie is another good exploration of the concept. The titular Tomie, a deathless monster in the guise of a gorgeous woman, has unearthly beauty that causes any man who beholds her to fall madly in love with her and deep into her manipulative grasp. If you get the chance to check any of those out, I’d encourage you to do so. It might make you think of love first when thinking of horror. After all, two of the biggest emotions that drive Japanese horror fiction are love and–

Loneliness

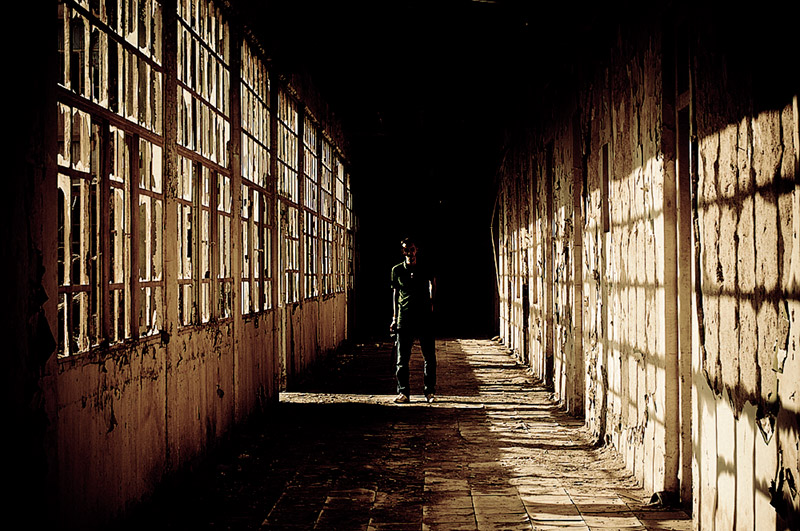

Despair coming from intense feelings of loneliness and isolation is one of the main vehicles for scares in Japanese horror. Nothing generates fear faster than being in a situation where you feel that you need help and there’s no one there to save you. We can’t help it, we’re social animals. This sense can be created by positioning your character in situations where he or she is alone and in harm’s way, but more often than not it’s also helped by the use of claustrophobic environments.

This is done in part by choice of setting—small dilapidated houses or apartment buildings, empty hallways in abandoned buildings, dark corridors down Tokyo side streets—but visual mediums have additional tricks to employ. In cinema, the use of low angle shots help create a sense of isolation by cutting off the peripheral views and making the subject look encased by the surroundings. Color palette can also be used. Saturating the frame with browns, greens, and blues creates a dark tone that is reminiscent of smog and urban sprawl making the characters seem alone in a larger, uncaring environment. Manga has its own set of tricks because panel size, panel spacing, and use of form and line can all make environments seem to shrink around their subjects.

This idea of isolation or exile can be particularly effective for ghost stories. Let’s take these two cases for example, because, yes, Japanese horror has at least two cases of women being thrown into a well: Sadako Yamamura from “Ringu” and Okiku from the classic ghost story “Banchō Sarayashiki.” These two, when they inevitably return as ghosts, are not only spiritually exiled from the world, but physically exiled due to having their bodies thrown into the confines of a well. This allows audiences to relate to the isolation and hatred they must have felt. However, it also makes the exiled women themselves things to be feared because of their separation from our world, creating a sense of anxiety and–

Insecurity

The type of insecurity I am referring to here is not necessarily a lack of confidence in oneself (although that can be a trait of a horror character seeing as it can make protagonists sympathetic or give antagonists vile motivations) but of a driving desire for stability that horror tends to flip right on its head. People have a tendency to desire safety through stability and constancy. The very prospect of horror introduces a force that disrupts just that in the character’s lives. Forces beyond individual control change things and the people are in need of reassurance and security. In this way, insecurity represents a natural human fear of change.

The Japanese are often criticized as a highly xenophobic nation. The claims can be exaggerated, but they aren’t too far from the reality of the situation. Japan is a very homogenized society and is highly custom-based. Foreign things that enter into that culture without appropriation are often unsettling to people that are very much reliant on the status quo. It isn’t just strangers from other nationalities that are unsettling, it is the very idea of strangers and what they represent: that which is unknown. This is based on preconceived notions of a “village” social model where people that would interact on a daily basis would get to know each other. In modern times, Japan’s crowded cities don’t often let that be the case. As Timothy Iles, Assistant Professor of Pacific and Asian Studies at Victoria University, puts it:

Horror represents the inchoate fears of an urban citizenry who daily encounter strangers—countless scores of unknown people, whose motives, desires, and potential capacity for harm remain immeasurable. These unknown people are all potential opponents. They are all potentially in competition for the very things each individual wants, yet whose true desires, because they remain unknown, are potentially far more threatening than they were in the ‘traditional’ pre-modern ‘village’ social model

This insecurity is a big component of Japanese horror. This is the reason that most modern Japanese horror stories play up the urban environments and the difficulties of everyday life. The instability that change represents is also the reason why many turn of the 21st century Japanese horror films have a technological aspect: “Chakushin Ari” (2003) deals with the proliferation of cellular phones, “Kairo” (2001) deals with computer technology, and “Ringu” (1998) with home video . The rapid advancement in technology changes the landscape and that unsettles people who are hoping that everything will be the same, and that everything will be okay.

If you take this emotion to its extreme you get a sense of paranoia and delusion that can also make for very effective horror characters—characters that become obsessively afraid and let that become their downfall. If you have the time to sink into a 13-episode anime series, I’d recommend “Paranoia Agent” for this understanding of how insecurity and anxiety, as well as the prevalence of information technology, can lead to a gripping paranoia with widespread consequences. Also, it’s a great show.

Delving Further into the Darkness

It’s important to look at how horror functions not just at the intellectual level but at the emotional level. Next time you are watching a Japanese horror movie or thumbing through a Junji Ito manga think about the ways the creators might be using these emotional themes to get under your skin and creep you out. Again, I think there’s more that I can say about Japanese horror (can you tell I’m a fan?), so join me next time when I go another step deeper and talk about motifs and iconography. Until then, I urge you to put aside some time in this new year to dive into some Japanese horror!