If someone tells you to go to hell, book your flight to Japan. There are plenty of hells to chose from! Different religious and folklore traditions combined with Japan's natural volcanic activity have created some fascinating, if terrifying, visions of the afterlife. Let's take a look, if you're brave enough.

Shinto Hell

Let's start our tour of Japanese hells with the hell of Japan's native Shinto religion. Yomi-no-Kuni 黄泉の 国 is the Shinto underworld as described in the Kojiki, Japan's oldest chronicle and source for many Shinto beliefs across the centuries. Yomi-no-Kuni, sometimes called simply Yomi, is a place that has more in common with the Ancient Greek or Roman ideas of the afterlife than Christian or Buddhist hells. Early translations of the Kojiki in English used the word "Hades" for Yomi-no-Kuni. Yomi 黄泉 literally means 'yellow springs' and the characters are also used in China to describe Huángquán, the Chinese realm of the dead. The characters yomi 黄泉 are also used in some Japanese Christian texts to refer to Christian hell.

Shinto hell isn't a very hellish hell. There's no fire, or torture. Yomi is not very well defined beyond being a shadowy land of the dead, but it is thought to be under the ground as it is the third in a triad of realms described in the Kojiki. Takamahara takamahara 高天原 was a heavenly realm, located in the sky and Ashihara-no-Nakatsukuni 葦原の 中つ 国 was located on earth. Yomi-no-Kuni was ruled over by Izanami, one of the creator gods of Japanese mythology.

The main tale involving Yomi in the Kojiki is about Izanagi, the other creator god trying to rescue Izanami after her death. Izanagi went to Yomi to find his counterpart goddess Izanami, who had died. At first she hid from him, telling him that she could not leave because she had eaten the food of the underworld (anyone with familiar with Greek mythology will see the parallels with Persephone here.) Izanagi persisted and wouldn't leave Izanami. She told him she would ask to leave, but that he must not look at her.

Izanagi promised not to, but quickly broke his promise while she was sleeping. He set his comb on fire (as one does) to see through the shadows of Yomi. When he saw Izanami's rotting, maggot-infested flesh he flipped out and ran away from Izanami and Yomi. Izanami woke up and was not impressed by her consort's reaction and broken promise. She sent Yomotsu-shikome 黄泉醜女, the hags of the underworld, to chase him. When Izanagi escaped the hags, Izanami also sent Raijin, Shinto gods of thunder after him before joining in the chase herself.

Despite her efforts, Izanagi escaped from Yomi-no-Kuni and sealed up the entrance with a boulder. Izanami was pretty ticked off to say the least and she shouted from behind the boulder that she would end the life of 1000 people every day as long as Izanagi stayed away from her. Izanagi replied that he would give life to 150,000 people everyday. He then declared Yomi-no-Kuni a defiled and unpure land. This fits in with the general Shinto belief that anything connected with death is unclean and impure – for instance, many people have Shinto weddings, but Buddhist funerals. Shinto prefers to deal with life. Buddishm on the other hand…

Buddhist Hell

Jigoku 地獄, Buddhist hell, is a lot more hellish than Shinto hell. It's got your demons and your fire and all the punishment you might expect. When I first came across the idea of Buddhist hell, I was surprised. I had always thought of Buddhism as a peaceful religion that believed in reincarnation after death. We have to keep in mind that there are a lot of different Buddhist sects in Japan and across the world. Some of them teach that there is a sliding scale of reincarnation. If you live a good life, you will be reincarnated into a better life until you reach Nirvana. However, there's the other end of the scale too: If you live a life that is not worthy of reincarnation, you might find yourself in one of the Buddhist hells.

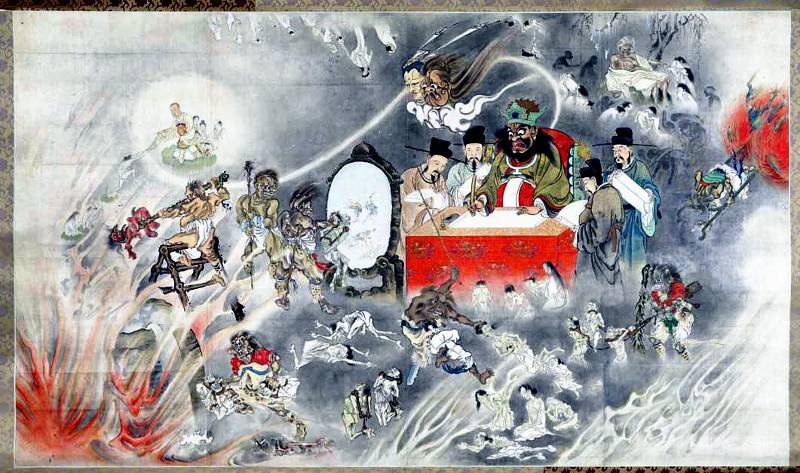

Buddhist hells are depicted in jigoku-zōshi 地獄草紙, hell scrolls. If you want to see some examples, you can find them in the Tokyo National Museum and the Nara National Museum. These scrolls were made in the 12th Century, towards the end of the Heian period. They depict through pictures and writing the inventively unpleasant hells awaiting you after death if you don't live a good Buddhist life. On the Nara scroll, apart from the eight main hells, there are also sixteen lesser hells; The Black Sand Cloud, Excrement, The Five Prongs, Starvation, Searing Thirst, Pus and Blood, The Single Bronze Cauldron, Many Bronze Cauldrons, The Iron Mortar, Measures, The Flaming Cock, The River of Ashes, The Grinder, Sword Leaves, Foxes and Wolves, and Freezing Ice. The names tell you exactly what you are getting. For example, the hell of The Flaming Cock has a giant fire breathing chicken. Very straightforward, if terrifying.

So although Jigoku is considered one location, it is subdivided into many different hells. It's hard to pin down exactly how many hells there are, with some counts putting the number at 64,000 and others at eight. The scrolls seem to generally agree on eight (sometimes sixteen – eight hot, eight cold) major hells, but these can be subdivided into more specific hells. The Tokyo scroll, for example, depicts four subdivisions of the major Hell of Cloud, Fire, and Mist. In Pure Land Buddhism the eight main hells are:

- Toukatsu Jigoku – The Reviving Hell

- Kokujou Jigoku – The Hell of Black Rope

- Shugou Jigoku – The Crushing Hell

- Kyoukan Jigoku – The Screaming Hell

- Dai-kyoukan Jigoku – The Hell of Great Screaming (and you thought the screaming hell was bad.)

- Jounetsu Jigoku – The Burning Hell

- Dai-jounetsu Jigoku – The Great Burning Hell

- Mugen Jigoku – The Hell of Unending Suffering

Different hells are reserved for different crimes. So if you commit murder (including the murder of animals) then you'll end up in the Reviving Hell where Oni will beat you to death, only for you to be revived and killed all over again. (And you though the reviving hell sounded like a good one.) But if you are a murderer and a lecher and an alcoholic, you'll be sent to the Screaming Hell to be roasted and boiled.

By this point you're probably losing track of all the hells. And I haven't even touched on Meido, the afterlife stage that comes before hell, that will have to wait for another time. Don't worry though, the hells have a well organised bureaucracy to make sure you end up exactly where you belong.

Hellish bureaucracy

Let's start at the top with the King of Hell. King Enma 閻魔王 rules over the Buddhist hells. He is the Japanese counterpart of Yama, the King of Hell found in sects of Buddhism across East Asia, including China. He was originally an import from Hindu beliefs. Enma is ingrained in Japanese culture, with parents even telling their children:

- 嘘をつけばと閻魔さまに舌を抜かれる

- If you lie, Lord Enma will pull out your tongue.

King Enma doesn't have time to look after all those hells personally, so he delegates. This belief was heavily influenced by Chinese Buddhism's tradition of the Ten Courts of Hell, where each court was presided over by a different King. As I mentioned before, ending up in Jigoku was not an eternal damnation. These courts are how you can escape hell and return to the cycle of reincarnation.

The trials are held after a certain length of time has passed after death and are each presided over by a different king. After 100 days, you are tried by King Byoudou. If you fail this trail, your next chance comes one year after you died, in the court of King Toshi. If you fail again, then you have to wait until the two year mark, then again for the six year anniversary of your death, and then the twelfth anniversary if you fail that trial. The final trial occurs 32 years after you died.

At this point you might be asking what you can do to speed your exit from hell. Well, it depends on a combination of your own conduct and repentance and the prayers of your family. Memorial services are sometimes held on each of these anniversary dates to help a deceased family member in their trails. You can read more about these memorial services in Tofugu's recent interview with a Buddhist monk.

With all the kings busy in court, those sinners won't torture themselves. That's where Oni 鬼 come in to do the dirty work.

Oni is often translated as demon, and the word is a pretty good fit. Oni do the hands-on jobs in hell, whether it's tearing people with their claws, filling a sinner's stomach with metal balls, or roasting people over pits of fire. Despite these rather terrible actions, oni have a more ambiguous place in Japanese culture than you might imagine. They also appear in folklore, in stories such as Momotaro, where they are less hellish and more like ogres or trolls. They are easily recognisable by their horns, spiked clubs, and wild hair, and while they come in all different colours, the most common are red and blue, often in a pair. While these oni are almost always cast as the bad guys, they aren't the terrifying demons from Buddhist hells scrolls. Oni appear in lots of media meant for children. They also lend their name to the Japanese version of hide-and-seek: Kakure Oni 隠れ 鬼.

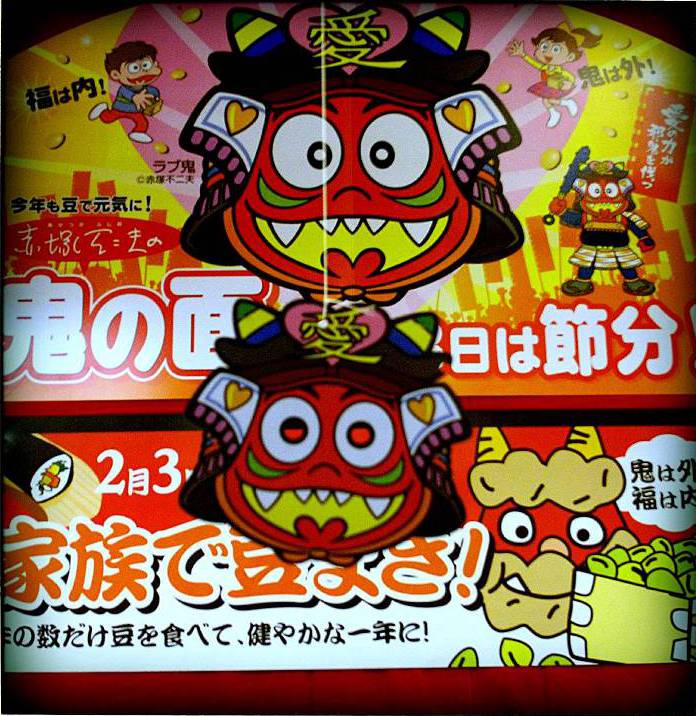

One of the most common traditions that features oni is mamemaki at Setsubun. Setsubun 節分 is the festival of the changing seasons in Spring and mamemaki began in the Muromachi period (1337 to 1573). Originally it was the job of the toshiotoko 年男, a male member of the family born in the corresponding zodiac year, to throw roasted soybeans, called fukumame 福豆 (lucky beans) outside the house. These days the tradition continues with kids throwing soybeans (or sometimes chocolates) and shouting:

- 鬼は 外! 福は 内!

- Demons get out! Luck come in!

The tradition often involves an adult dressing up in an oni mask and lots of screaming kindergarteners. The masks are usually pretty cute and the Setsubun oni are far from the Jigoku oni in terms of terror.

Hell on Earth

Hells have been a fertile ground for Japanese art for a long time and they are certainly not restricted only to religious works. The Hell Scrolls themselves are beautiful if disturbing pieces of art. Author Ryūnosuke Akutagawa wrote a story called Hell Screen jigokuhen 地獄変 about a painter who tortures his apprentices so that he can complete a masterful depiction of hell based on their suffering.

The 1960 movie Jigoku (English Title: The Sinners in Hell) was unique among horror films of its time due to its graphic and gory depictions of hell. Tales of murder, adultery, revenge and deceit are all twisted together and pretty much the whole cast gets their comeuppance. The film was the last one made by Shintoho Studio and critics of the time joked that the movie killed the studio and took it to hell.

Buddhist hell continues to influence Japanese art, albeit often in a lighter mood these days. Hōzuki no Reitetsu is a manga and anime about a demon working for Enma the King of Hell. It's a comedy that plays on many specific Japanese tropes, such as the story of Momotaro. Central to the plot is the different levels of hell and the bureaucracy required to keep them all running smoothly. The focus is firmly on the demons, not the sinners. After reading this article you might not think hell is much of a laughing matter, but if you can get through the thick Japanese cultural references, Hōzuki no Reitetsu is pretty funny.

You can find references to Shinto hell in pop-culture too. The gateway between Yomi and our world, yomotsu hirasaka, gives its name to a location in the video game Persona 4 and a ninja technique in Naruto. The manga Kamisama Hajimemashita uses Yomi-No-Kuni as a setting in a way that is closer to its traditional depiction as an underworld.

Go to Hell(s)

If you want to visit hells in Japan, you're in luck! You have a quite a few choices. It might seem strange to think of hell as a tourist destinations, but they are very popular. Most are centred around volcanic activity, and when you see boiling mud, geysers and the extraordinary colours of the rocks, it's easy to see why people think these places are hellish.

Beppu

One of the most famous hell sights is Beppu in Ōita Prefecture on the southern island of Kyushu. While the Beppu hells are mostly a tourist attraction, complete with Japanese stamp rally and rather depressing small zoos, they do have religious significance for some visitors.

Human beings need to experience hell in this life at least once, to empty themselves of superfluous accumulations, to reflect on their past conduct, and to contemplate the path ahead. For this important purpose, I highly recommend a visit to Beppu to witness the many aspects of hell. Only those who have been through hell and lived to recount the experience, are worthy to be called real human beings. –Writer and Buddhist priest Kon Toukou

If you see Beppu as hell on earth, then a visit there would make you think twice about your conduct in this life. The hot springs of the Beppu hells are far hotter than most hot springs you can visit in Japan. If you mistook them for onsen hot springs and tried to take a bath, you would have a very bad time.

I can't really recommend the hells at Beppu to visitors, not because of the hells themselves, but because of the industry surrounding them. If you don't like seeing sad animals in cages, give Beppu's hells a miss, or at least the ones with animals.

Noboribetsu

I can however, recommend another hell – Noboribetsu. Noboribetsu is located in Hokkaido, about an hour from Sapporo by train. It's claim to hellishness lies in the Jigokudani, or Hell Valley. This area of blasted volcanic activity, with steam and sulphurous smells rising from the rock, certainly looks hellish. It is one of the Japanese Ministry of Environment's top 100 fragrant landscapes, even though the fragrance isn't all that pleasant! The real attraction is the town of Noboribetsu-onsen 登別温泉. It is one of Japan's top hot spring resorts and the largest one in Hokkaido. You can safely skip the bear park which is located someway out of town. As well as having numerous onsen and hotels, Noboribetsu is also relentlessly hell and oni themed. There are 11 oni statues in Noboribetsu, including the Business Demon, the Romance Demon, and the Train Station Welcome Demon.

The shops in Noboribetsu sell oni in every imaginable form. The town even has a unique way of celebrating Setsubun and mamemaki. Instead of chanting, "Oni wa soto!" (Demon's get out!) the residents chant "Oni wa uchi!" (Demons come in!) because it is thanks to oni and their hellish association that the town prospers. Another highlight is the shrine to King Enma. Depending on what time you visit, he will either show you his kindly or his angry face.

If you want the full hell experience, go for the Jigoku Matsuri, or Hell Festival, which is held in late August. All the fun of a Japanese festival, but with added oni! The festival celebrates the opening of the door to hell, which is supposedly located in Noboribetsu. You might not think this would be a cause for celebration, but it's no stranger than many of Japan's other festivals!

Animatronic Hell

The town of Kurume in Kyushu is largely unremarkable, apart from the fact it has a giant 62 meter tall statue of Kanon towering over it. The Jibo Kanon statue is inside the Naritasan temple grounds. It is a place of pilgrimage for women who have lost or aborted babies. It's not just impressive to look at, but you can also go inside. If you climb up inside the white concrete statue you will find images depicting Buddha interceding on the behalf of unborn children until at the top there is a shrine showing them in heaven. However, if you go down into the basement, you'll find animatronic hell. Here is the entrance:

You can get an idea of what's coming from the charming skull and bones decor. Punishments described in the hell scrolls are recreated in moving models of demons torturing people. As you walk through they are activated and begin their grisly actions. Photography is not allowed inside, but I'm not sure I'd want to share the images with you anyway. When I visited, a family was there at the same time. At first the little boy was excited to go in, but by the end he was crying and screaming that he wanted to leave.

After your walk through animatronic hell, you emerge into a scene of Buddha surrounded by peaceful animals in a garden. The message is clear: be a good Buddhist or you'll end up in hell. This experience changed my view of Buddhism in Japan and made me want to investigate the ideas behind Buddhist hell. If you are in the area, I think it's worth a visit, but it's not for those who are easily creeped out by demonic mannequins.

Yomotsu hirasaka

If you want to visit Shinto hell, Yomi-No-Kuni, you'll have to take a trip to what used be called Izumo Province, but is now the eastern part of Shimane Prefecture. The entrance, known as Yomotsu hirasaka 黄泉津平坂, is found there, but you won't be able to get in. Remember how Izanagi sealed it with a huge boulder? Well that pretty much cut off Yomi-no-Kuni as a pre-deceased tourist destination. You can still visit the Shinto Shrine there though. It is a gloomy place, but that seems appropriate.

In Japan you can find hells to suit all kinds of tastes, from comedies and cute oni to geological and artistic marvels that make you reconsider your life. I think Japanese hell is worth a visit, though hopefully just as a day trip.