Food is a great way to share culture, but sometimes it can be difficult. Like any other art, certain cultures value certain traits more than others. What's delicious to one may be disgusting to another. Add difficulty obtaining ingredients due to price, season, or general scarcity, combined with differences in cooking techniques, and even food itself can become lost in translation.

Thus, this list. While Japan is often accused of having "weird" food, it's simply a reinterpretation based on local culture. Often we can still find the spirit of the original dish, and hopefully, by discussing some of the origins, we can see how even our own local favorite "ethnic" food might have been adapted for our own culture's taste buds.

1. Pizza

The first time I visited Japan, my family friends thought it would be good to give me something "American" for dinner, to help my stomach adjust to the long flight, lack of sleep, and different weather. What I got was a mayonnaise, corn, "sausage" pizza (wait for my section on sausage). I'd never had any of those ingredients on a pizza since, well, we don't really do that in the states. I was going to say it was "wrong", but despite not liking sushi at the time, I immediately thought of California rolls and a Japanese friend I knew who had complained about fake Japanese food. Rather than shutting my mouth, I accepted the difference and tried to embrace it. I didn't really enjoy it that time, but future adventures went much better.

I feel like pizza is a good place for us to start, because it is one food I feel like is both universal and also…not. For those unaware, there are actually guidelines for what a real Neapolitan pizza is. That's pretty hardcore, not just because a government would outline what allows a food to be called by a certain name, but also because it dictates the region the ingredients must come from. It certainly makes it hard for even Americans to say they've had the "real" thing, but maybe that's okay.

A wise geek has mentioned that pizza is the people's food and, in the old days, was pretty much just dough, cheese, and whatever you had around. In fact, the tomato part of pizza came from America, so while it was created in Italy, its current form is rather modern. In that sense, we shouldn't be too surprised when Japanese people use toppings like shrimp, canned tuna, avocado, seaweed, or even squid ink on their pizza.

I know there are some well known differences between the two regions' pizza styles on the web, but from people I know, the big differences for modern Italian pizza when compared to American pizza (which can be applied to most Japanese pizzas too) are the consistently thinner, wood-fire baked crust, less but fresher tomato sauce or just chopped tomato, lighter amount of cheese, and fewer toppings, especially in terms of the kinds of meat you can use. Pepperoni isn't a kind of meat in Italy because it's the name of a bell pepper in Italy; the meat is an American creation with a confusing name for real Italians.

In that sense, both Japanese pizza and American pizza are odd but normal. Odd in that an Italian weaned on Neapolitan pizza may be surprised that corn is the most popular pizza topping in some Japanese pizza places. But that's okay since, much like the creation of pizza, the spirit of using American vegetables is still being upheld. Oh, and using whatever's around and delicious as a topping. Or something like that. It's normal to use local ingredients, and that's where we'll rest this debate.

2. Cheese

The above photo exemplifies most of the cheese you will find in Japan without visiting an import store: heavily processed, plastic wrapped cheese with no specific name. Honestly, whenever presented with these non-Kraft singles, I ask people what kind of cheese it is. Most people look at the package, and then I list a few names, like gouda and cheddar, which can be found at import stores or some really nice super markets. Then they laugh and usually answer "mild." Which is a pretty friendly way of saying, "This doesn't have a taste and may just be tofu mixed with plastic."

As a processed cheese, it's probably at least a type of what we'd call "American cheese." Oh, there's cheese in there, but there's so many other ingredients that, even by American standards, you can't really call it cheese. This is important because, although cheese is popular in America, we don't eat "raw" cheese, cheese that's been made from unpasteurized milk. The pasteurization process is supposed to make the cheese safe from certain bacteria, but it also changes the flavor, which is why you'll often hear French people dissing American cheese.

Of course, this assumes you like the taste of cheese. There's a reason that Japan uses a lot of processed cheese: it's pretty much a fatty, spoiled milk byproduct. How many readers can actually say they like stinky cheeses like limburger? Keeping in mind that Japan's Buddhist influences upheld a ban on eating (most) four-legged animals until 1867, and that cattle were work animals before this, Japan's history with cheese may seem short. However, despite the fact that it wasn't really popular until the Meiji era, cheese actually was present in Japan around 700 AD from China. Obviously it didn't do so well, since most cheese in Japan is very processed and/or very mild these days.

3. Mexican Food

This one's probably a bit tame and decently well known: takoraisu (or Taco Rice). It's "Mexican" food made in Okinawa that's popular with foreigners. I personally can barely stand the stuff. The "salsa" usually tastes like a sweet, slightly spicy ketchup. It doesn't always include cheese, and sometimes uses cabbage instead of lettuce. However, most tacos Americans know (including myself!) are actually Tex-mex, so you can blame this one on America. Why? Two big hints if you look at a recipe for takoraisu: cumin and beef.

Mexican chefs from Mexico have noted that real Mexican food usually doesn't have beef or cumin. For meat, most Mexican people eat a lot of chicken and pork, unless they live very far north or are ranchers. Cumin, on the other hand, is another "northern" ingredient. Cumin is relatively new to Mexican cooking, being imported from India via the US or England.

In this sense, I can understand why some Japanese "Mexican" food is just so different from some of the better Mexican food I've had (made by Mexicans who moved to the states or Mexican-Americans who try to uphold their parents' culture). As some Mexicans might tell you, American Mexican food can be rather mild to suit American tastes that may not be able to handle as much heat. Transferred again to Japan, where, despite having spice-loving neighbors like China and Korea, spicy food isn't very popular. So some of the changes make sense. On the plus side though, Japanese people will use more white cheese like traditional Mexican cooking does. However when you have food that actually includes a tortilla, like burritos, corn tortillas are replaced with wheat.

4. Corn Dogs

In Japan, it's called an "American dog," but sadly, it's yet another food Americans can't exactly claim; corn dogs were created by German immigrants to Texas who wanted to sell more sausages. While the stick may have come later, the original recipe did, in fact, use corn meal, which is a bit odd considering that older Germans have told me they grew up thinking of corn as animal feed unfit for human consumption. Heck, my old German teacher freaked out her German roommates when she was studying abroad and they found her eating a big can of something they only expected pigs to eat. Oddly enough, though Germans aren't traditionally corn eaters, they do eat some now, and as per one of my friends from college, Germans now eat corn on pizza.

So what's the big deal? Even though they love corn, Japanese use wheat flour for American dogs. Don't ask why, since I've yet to find out, but corn meal just isn't made out here. No one can tell me why.

5. Sausage

I know I've mentioned her before, but I met a German sausage enthusiast in Japan. I hadn't had a decent sausage in awhile, and she was hurt concerning the reactions to her food. Most people were saying her bratwurst were too spicy, and she kept trying to assure me that it was a traditional, mild recipe, so I picked one up. I've had sausage at least made by Germans who love their food heritage in the states, but aside from the small size (most food gets smaller in Japan), the taste was the same: juicy coarse cut meat and just enough pepper to let you know it's there.

As I said earlier, Japanese people aren't good with spicy. They're more into mild tastes, so it shouldn't come as a huge surprise to say that the first Japanese "sausage" I tried tasted more like a hot dog. Nothing wrong with hot dogs, but don't exactly blame this on America. While popular in the states, its origins lie in Austria.

Hot dogs are a mildly spiced (if at all) type of sausage that are made of finely chopped meat (if meat is used), whereas other sausages tend to be more spiced with coarse cuts of meat. In addition, hot dogs are pre-cooked, while sausages can be sold raw. The "sausage" I've had on several pizzas in Japan were certainly pre-cooked, lightly spiced, and used finely chopped meat, much like that fish sausage/hot dog above.

To be frank, I can't say I've seen a lot of sausage in Japan outside of Tokyo, including at Oktoberfests. Again, using the above description, a lot of what is labelled as "sausage" here is very mild, pre-cooked, and finely chopped. It's not bad at all, but it's not what I'm used to getting when I think of sausage.

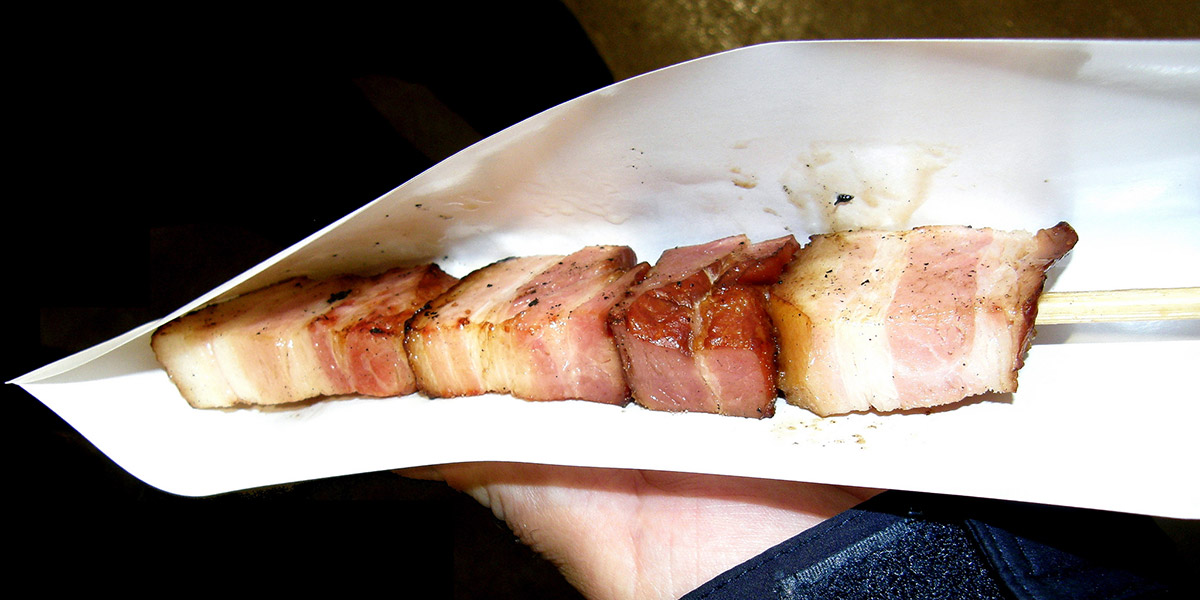

6. Bacon

Koichi spoke about this, so I'll try to expand on what he's brought to the fight so far. Bacon can actually be a little flexible from country to country, but at it's core, it's meat cured either in a brine or through dry packing, usually with salt and can be smoked or boiled. Usually it's pork, but the location of where on the pig it originates from varies. Americans love their pork belly bacon, while Canadian bacon is taken from the back of the animal. Oddly enough, the Canadians have bacon from other parts of the animal, as do Europeans. I guess that's why we're a bit picky about bacon.

Those who have eaten Japanese bacon are sometimes confused and upset by the taste though. When cut into cubes and grilled over a fire, it's not bad, but it often reminds people of ham. While, like America, Japan uses pork belly for bacon, Japanese bacon is pre-cooked, meaning you can eat it right from the bag. Americans reading this might have made the connection by now, but if not, it's similar to ham in the states, which undergoes a decent amount of curing, cooking, or general processing so that few hams Americans encounter are truly "raw."

As a bonus, "ham" in Japanese is totally different from English. While our hams are usually pork thighs (or sometimes turkey), in Japan, it's pretty much just processed meat, not just from pigs. It includes prosciutto, but sliced chicken breast has been called "ham" by some of my Japanese co-workers.

7. Curry

This one's a bit tough, since, like pizza, it's become very international. At the same time, it's been an Indian staple for thousands of years, and at the very least, it's traditionally made with ginger, turmeric, and garlic with some rice on the side. The Japanese have the bare basics down, but their version is pretty different from what I expect from Indian curry. This time, though, we can blame the Brits, who introduced curry after the opening of Japan. Although Buddhism was passed down to Japan from India, curry was somehow left behind. It was the British who gave curry a ride to the land of the rising sun. Oddly enough though, Japanese curry's claim to fame is a roux, a traditionally French technique.

Now, I could just say, "It's milder and uses a roux," but that seems a bit too simplistic. Instead, let's first compare ingredients from the above link. Indian curry uses many more spices than Japanese curry. Japanese curry, conversely, uses several fruits and meats, as well as udon noodles as ingredients. It's not that Indian curry doesn't use other ingredients, but it's usually more about the spice and uses fewer ingredients. Speaking as someone who's tried the lifestyle and has a sibling who still upholds it, Indian curry is also more vegetarian friendly than Japanese curry. Still, if you think this is a bit too broad, let's go with a recipe comparison.

This was a bit tough, since even the most home-made Japanese curry recipes at least use pre-mixed spices like garam masala, but I just found a comparable recipe that also used it and other similar ingredients. Both recipes are for a kind of butter chicken curry. Starting with the garam masala, the Indian recipe uses 1/4 less than the Japanese version, but also uses more of a variety of spices: cinnamon, cloves, chili powder, fenugreek leaf powder, and ginger, but no cayenne like the Japanese version. Both use tomato, but the Japanese version uses ketchup or tomato paste, while the Indian one uses a puree. The Indian version has more tomato, but the Japanese one also uses tonkatsu sauce, so we already can see the Japanese one will be sweeter. The Indian recipe uses honey, but the Japanese version uses a whole apple. Finally, both use dairy to help keep things cool, but the Indian recipe uses butter and cream while the Japanese just uses butter. I think you can see how things differ.

8. Char siu

Now this is something I really miss from less Americanized Chinese places (and Hawaiian restaurants): char siu, a Cantonese method of cooking (traditionally) pork. Think barbecue, both in cooking method and in taste: it's a bit salty, a bit sweet, smokey, and delicious. For some reason, the Japanese changed it. You may now know it as "chashu," and while the change happened centuries ago, the name similarity is enough that even a foreigner to both Chinese and Japanese culture (like me) is able to hear the similarities between the two and make the connection.

In Japan, instead of using a nice fire, the pork (just loin) is rolled, braised, and lacks five spice and sugar. Oh, and the modern day food coloring addition. It's certainly less colorful, but still rather good, despite the name taunting those of us who know its origins. Chashu's pretty good on it's own, which is why it's ramen's best friend, but not everyone agrees with the changes.

9. Cheesecake

Just looking at this picture makes me a little sad. It's not that Japanese people can't make cheesecakes, nor that souffle cheesecakes are bad (hint:they're not!). But the cheesecake made in Japan really is nothing like what I'm used to. I think of cheesecake as a rather decadent dessert. In Japan, it's… not. If you go by a basic definition, what Japan makes is certainly cheesecakes. However, what I like in the states is called "baked cheesecake." For me, it'd be like buying "baked bread." I see it as the food's default state. No, in Japan, cheesecake here often seems to be something different.

Finally, we have a food that at least I feel comfortable enough to call "American," and not because it naturally grows there! Cream cheese is actually an American food, being made by failing to recreate Neufchâtel cheese to make something richer and creamer. While other cheeses are used in other countries, Japan's cheesecake is described as seeming a bit plasticky, probably due to the way it emulsifies its ingredients. Cornstarch and flour aren't ingredients I think of being in cheesecake (unless it's made by a cheap restaurant or used in the crust), but the very first recipe on a popular Japanese recipe site uses it for a "baked cheesecake." This makes the cheesecake less dense and less sweet, but that's not the first thing Japan does differently.

"Rare" cheesecake is what we'd call "no bake" cheesecake in the states. This recipe's no-bake cheesecake method is pretty much what I'm used to. Yeah, it's a bit less "cheesecake" and uses cream, but it's still pretty rich. In Japan, they sometimes use gelatin, yogurt, or milk. Once again, these make the cheesecake less dense and less sweet, which is fine, but certainly not what my American stomach craves when it thinks cheesecake.

The most different style cheesecake, though, is the souffle. A simple google search will result in recipes that constantly call it "Japanese Souffle Cheesecake" because, well, it really is a Japanese creation. Again looking to popular Japanese recipes, we see not only substitutions to cut back on the cream cheese (such as using whipping or sour cream), but the addition of yogurt and use of cake flour. While this is a light, fluffy, subtle cake sure to please someone with a delicate palate. However, those with a carnal desire for unadulterated American cheesecake will certainly be in for an unpleasant surprise. Just see if there is any "baked cheesecake" and live with the fact that it'll be milder than what you're used to.

10. Western Breakfast

Just searching Google in Japanese for waffles and pancakes will visually show you the difference, but for those too lazy to click the link, here's the hint: they're desserts. While I know many Americans joke about this, I think if you want to a restaurant and saw pancakes or waffles on the dessert menu, you'd be pretty confused. I know I was the first time I played Tomodachi Life in English and found both foods in the dessert section, and one looking much smaller than I'd anticipated.

Pancakes are sometimes a little sweet. Fruit and whipped cream aren't that uncommon, but if you look at the Japanese Google results, you see far more of that than maple syrup, butter, and bacon being served along side a stack of pancakes. It isn't entirely sweet in Japan though. No, I'm not talking about savory crepes. While I haven't tried them, I was assured they were becoming popular. One site shows things like curry pancakes, tomato pancakes, Christmas cake pancakes, and cheese fondue pancakes. It's also got the more traditional variety we're used to, but the Japanese pancakes certainly make use of local tastes to experiment with the form.

Waffles, on the other hand, seem much more limited to sweets. I've been told you can find American style waffles in some places, but overall, Japanese waffles are more like soft cookies, which is exactly how they appear in Tomodachi Life. While you may imagine Belgian waffles as the definition of waffles, those are actually American waffles based on Belgian styles (notice the s!). Despite sometimes calling them "Belgian Waffles," Japanese waffles are more similar to Liège waffles, a (real) Belgian style waffle that's richer and denser than what Americans eat (and oddly, the opposite translation of the Japanese cheesecake!).

Now, while these are both a bit in between for Americans, any style is pretty acceptable, since historically, both pancakes and waffles played both sides, with early pancakes using cheese sometimes and early waffles using orange blossom water.

Bon Appétit

So, there you have it! Ten foods pulled from around the globe, translated differently in Japanese culture than what you might have expected which, perhaps, in turn, you didn't realize was different from it's original. Hopefully with this in mind, the next time you try another country's version of a pizza or pancake, you remember just how far the recipe's come from its humble origins!