TV reflects the obsessions of a culture, so there are interesting differences in the TV shows of different countries. Comparing American and Japanese TV, one subject where there's a big cultural difference is in shows about food.

Cooking on American TV is basically always nonfiction. Japan has this type of show too, so in both countries we can watch how-tos that teach us to cook elaborate dishes from scratch, whether we set foot in the kitchen ourselves or not. And for better or worse, there's been cross-fertilization: the US now owns the TV cooking competition, a genre we borrowed from Japan after the successful importing of Iron Chef (a show that I loved, but that I think now has a lot to answer for).

But in Japan there are also many series where cooking and food are a central element of fiction. In these series, chefs are main characters, average people are obsessed with a certain dish, and even the plot may turn on a particular detail of a special recipe or ingredient.

Sure, in the US we have shows where the characters gather to eat in a certain restaurant or bar. There was one old show, Alice, about a waitress in a diner, and historical shows like Upstairs, Downstairs and Downton Abbey may have a shot of the staff working on dinner while they're talking about something else. Maybe you can think of one or two more. Contrast this handful of shows with the fact that on a fansub site like gooddrama.net, there are enough shows with food that you can actually search for it as a separate genre, and that isn't all of them.

Numbers aren't the most important difference, though, because comparing those few shows to Japanese food drama is like comparing apples and oranges, or sushi and a Maine lobster roll. Take two tales that involve a soup-maker. You may have seen the Japanese movie Tampopo, where (in between other odd unrelated food-centric vignettes) the plot follows a woman who owns a ramen shop and is working to come up with the perfect recipe. We see her slaving over variations of broth and getting the advice of experts who make comments on her noodles like "They have sincerity, but lack substance." Compare this to the most famous soup-maker on American TV – the character on Seinfeld who's famous for yelling at people, not for obsessing about the details of his cooking.

The focus on culinary detail in Tampopo is far from unique. Japanese dramas reflect an obsession with the quality of food that isn't seen on American TV – reflecting the fact that it's also not, I'm sad to say, part of American culture.

Becoming A Chef

Let's start by looking at a particular sub-genre of the food genre in Japanese television shows. Yes, the story of "becoming a chef" seems to come up so often that I'm giving it its own category.

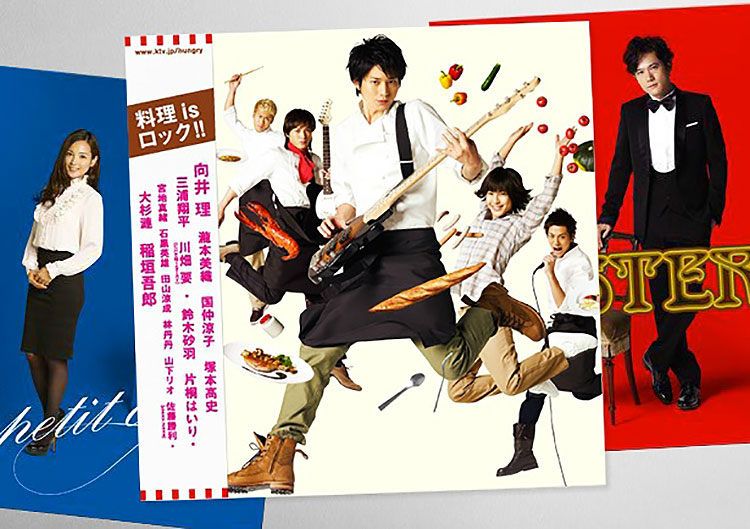

Western food: Hungry!

Start with a drama where the title fits this theme perfectly: Hungry! (Hanguri!). As a child, the main character, Yamate Eisuke, wanted to follow in the footsteps of his mother, a French chef with her own restaurant. Instead, he forms a rock band with three friends, but as the series opens, he's nearly 30 and they haven't broken through to the big time. He goes to his mother and tells her that he wants to return to her restaurant and study to be a chef again. Unfortunately this touching reunion is marred by the fact that his mother has a heart attack and drops dead.

Further complications ensue when he declares he's going to take over the restaurant: his father has already sold it to a rival restauranteur, who in the course of the series becomes obsessed with Eisuke, going back and forth between wanting to ruin him and trying to hire him. (A relevant side note is that this bad guy is played by Goro Inagaki, a member of SMAP, which is a band that has its own line of food products at Japanese 7-11s, something else we'd never see in the US.)

Along with that business rivalry, which turns very personal, there are romantic complications, fights with his friends – but even the interpersonal drama usually turns on the food. One character's family runs a small market garden nearby where the restaurant buys vegetables. She falls in love with Eisuke's cooking first and then, as a sort of side effect, with him. And the rival tries to make trouble by convincing that family to sell all their produce to his restaurant instead. I definitely can't think of an American series where the bad guy's plan of attack consists of buying up all the tomatoes.

And much of the emotional drama is about Eisuke's struggle to learn to be a French chef worthy of his mother's legacy- a process we watch in extreme detail. Don't watch this show when you are Hungry! yourself, because a huge amount of screen time is spent on shots of prepping, cooking, plating and serving French food. They're so serious, they present the name of the dish on-screen when it is served. In fact, they're so serious that there is a recipe book based on the series, and the star took French cooking lessons as part of his preparation for the drama.

Japanese food: Ando Natsu

Ando Natsu is a young woman with the dream of becoming a French baker. She starts as an apprentice at a cafe run by an older woman baker who she worships… who promptly drops dead. Watching these two dramas in succession, you get the feeling that making French food in Japan is not good for the lifespan.

With no idea what to do next, she stumbles into a wagashi shop in Asakusa. Wagashi are those exquisite traditional Japanese confections that are basically small edible works of art, made in different seasonal shapes including flowers. She sees that these sweets give the same joy to the customers as French pastry does, and asks to become an apprentice.

The title of this series and the character's name actually refers to sweets – Ando Natsu is a pun on An-donut (a doughnut filled with sweet bean paste) which is pronounced the same in Japanese, and other characters often tease her by referring to this pun.

This series also spends a lot of time in the kitchen, referencing how hard it is to make the beautifully detailed sweets, how long the apprenticeship lasts, and the menial tasks the beginner is saddled with. Natsu washes a lot of dishes and gets very excited every time she's allowed to do some simple part of the actual confection-making process for the first time.

Particular processes and ingredients in making wagashi are often central to the plots. In one episode, Natsu has to stay awake all night to supervise the fermenting of the starter for a special order for an important memorial service. She's called away for a time to prevent someone from committing suicide. (Yes, really. The writers of this series did not fear improbable melodrama.) She thinks it still looks OK when she gets back, but in the morning, the master tells her it's ruined. Fortunately, they're expecting a delivery of koji, the starter for fermentation, and might have just enough time to make a new batch – till they find out the delivery truck was in an accident, and all the containers overturned and spilled.

Natsu thinks she's solved the problem when she runs all over town and manages to buy a package of koji that comes from the same prefecture. Unfortunately, that's not close enough. She's crushed when they tell her they can't use it, that without the exact same koji, they can't claim to be selling the same sweets they've always made. The master explains in mystical detail that the skill of the chefs is nothing without the wind in the town, the atmosphere of the store, and the tiny living things in the koji.

You understand, this is like saying it's not worth baking bread if you can't get the same brand of yeast you've always used. For all I know this is true about wagashi, or even bread if you're a true connoisseur, but that fact sure wouldn't sustain that amount of drama in an American TV series.

Another element we see in Ando Natsu that frequently recurs in this type of drama is someone's longing for a favorite food from long ago. One episode is about a woman who comes to buy their persimmon-shaped sweet which is the favorite of her dying father. For complicated and dramatic reasons they no longer make this sweet, but Natsu finds the recipe and tries to replicate it. This effort to satisfy a dying customer gets her fired (temporarily) for trying to pass off her inferior beginner's work as the product of this revered generations-old shop. (Don't worry, there's a happy ending and the man does get his wagashi in the end.)

Cooking at Inns

Not all shows about professional cooks are set in restaurants. Some are about traditional inns, where the quality of the cuisine is a huge part of their reputation.

O-sen

O-sen, about an inn in Tokyo's old shitamachi neighborhood, is practically an education in traditional Japanese cooking. (Like some others of these shows, O-sen is based on a manga – there are also many manga where fictional plots, settings and characters are food-related.) As we watch the training of a character who's talked his way into a job in the kitchen without really understanding what this kind of cooking is all about, we learn about different kinds of miso, why a fire made of straw is best for cooking rice, and other details of extremely traditional Japanese cuisine.

O-sen is another show where a vital plot point turns on a particular ingredient. The cooks use a traditional hand-made katsuobushi, the dried bonito fish which is the fundamental ingredient in the broth used in nearly every Japanese dish, but is now mostly made in a more mass-produced way. The inn not only uses the hand-made variety, in fact they've always used the katsuobushi of one particular producer who is now threatened with being closed. Without this particular dried bonito, O-sen says, the taste will change, the food will no longer be their food, and the inn will have to go out of business.

There isn't space here for me to explain all the intrigue that swirls around this – but all I can say is, I wish I lived in a country where dried fish can be so important to a plot.

Kamo, Kyoto e Iku

Along with the longing for a favorite food from the past, another recurring theme is people's exquisitely accurate memory for such foods. Kamo, Kyoto e Iku is set in a traditional inn in Kyoto. One episode is about a couple who has been coming to the inn for 40 years. The woman, who's had a stroke, loves a tofu dish they serve, so her husband brings her to the inn so she can have it again. While she no longer recognizes her own husband, she remembers the taste of the dish well enough to be disappointed that it doesn't taste exactly the same. The inn's owner goes to the 200-year-old tofu store to ask what's happened. The tofu maker blows up at the suggestion that the tofu has changed, but eventually admits that the woman is right, that he's gotten too old to make it properly. The happy ending comes when he teaches a younger tofu-maker his method, and the woman gets to have exactly the dish she remembers one more time.

Not Just Professionals

You'll also find these elements in shows that aren't set in inns or restaurants and where the main characters aren't culinary professionals. My favorite example so far comes from Tokyo Bandwagon, which is about a family that runs an antique bookstore. In one episode the family is trying to reunite the cook from their local izakaya with a former momento. Long ago he wronged this man and can't believe he will ever forgive him. They invite the cook for a meal and present him with a dish of simmered turnip. One taste and he basically says "OMG, it's him!" and insists that no one else but his former master could have made that dish. He's proved right when the man steps into the room for a dramatic reconciliation. It's ridiculously improbable, but if you're a fan of Japanese food, how can you not love it? (What's more, how can you not weep with envy when they sit down to one of the family meals pictured above.)

I've also just started watching the first episode of a show called Lunch Queen. The main character is a waitress in a coffee shop who keeps a detailed notebook about places to go to eat lunch. A customer tries to convince her to pretend to be his fiancé as part of a ruse to approach his estranged family. She's having none of it – till he tells her that they own the restaurant that makes the best omu-rice in all of Japan. I can't wait to see what hijinks – and recipes – follow.