Koichi recently wrote an article entitled "Why Japanese Education Succeeds: Amae, Stress and Perseverence" – this article is meant to be a rejoinder exploring not really the successes of Japanese education (which there are many), but its limitations.

Now before I begin I need to state where I come from. I'm from Singapore (no that's not in China) with a similarly brutal Asian education system. That means that I will probably have a very different perspective on Japan's education system compared to the other writers. For example, one striking thing to Americans in Japan is perhaps the relatively low school dropout rates. To me however, that's taken for granted, as is the exam stress of the Japanese system.

But, anyway. As Koichi stated, there was (and still is) a trend to hail the Asian countries' education system. It may have shifted away from Japan specifically, but US President Obama's praising of the Korean education system shows that this trend is still going strong.

However, and to be very frank, whenever this happens, many of us on the other side of the Pacific just simply arch our eyebrows. Partly because we don't know how "bad" it is over on the other side – my friend talking about gang fights in his Los Angeles school was eye-opening to me. But also partly because on the flip side many Westerners have an overly rosy view of Asia and its education – it seems as if the education systems of Asia are praised more outside of Asia than within it.

Some of the stuff in this article is very generalizable to other Asian countries as well – there really are a lot of similarities. Some of it is specific to Japan – read on to find out.

Non-Cognitive Skills

Koichi in his article (I'm very sure I'm not doing it justice by summarizing here) pointed out that the amae as well the ganbare culture in Japanese society are the core reasons why the Japanese youth tend to stronger non-cognitive skills, which in turn leads in the long run to higher personal performance. This also translates to their ability to endure the punishing stress of the Japanese education system and life thereafter.

This is true in terms of perseverance, stress tolerance and conscientiousness. However, there are also other non-cognitive skills which cannot be lumped together with the above. Consider the following:

Self Confidence:

A survey published in 2011 (Source in Japanese) stated that 37.3% of Japanese high-schoolers "somewhat agreed" or "completely agreed" with the statement:

- 私は価値のある人間だと思う

- I am a human being with worth

This is contrasted with 75.3% in South Korea, 88.0% in China and 90.4% in the US.

Furthermore the same survey also asked whether participants agreed with the statement:

- 私は努力すれば大体のことができる

- I’ll be able to do most things if I put in effort

44.4% of Japanese participants agreed as compared to above 80% for the other countries. Therefore it's questionable whether Japanese students work so hard because they really believe they can achieve or because they're simply being pressured to do so.

Shyness:

Described as an "overgeneralized response to fear" in this article, Carducci and Zimbardo continue to say that Japan (along with Taiwan) display the highest shyness among surveyed countries and that:

In Japan, if a child tries and succeeds, the parents get the credit. So do the grandparents, teachers, coaches, even Buddha. If there's any left over, only then is it given to the child. But if the child tries and fails, the child is fully culpable and cannot blame anyone else. An "I can't win" belief takes hold, so that children of the culture never take a chance or do anything that will make them stand out. As the Japanese proverb states, "the nail that stands out is pounded down."

Curiosity:

An international survey conducted on adults by the OECD over 2011-2012 asked the question "Do you like learning new things". Japan had 20% of respondents answering "Not at all" or "Very Little", the highest number excluding South Korea which had near 29% answering so. 36.8% in Japan answered "to some extent", however the total for "to a high extent" and "to a very high extent" (42%) was significantly lower than other surveyed countries, except for South Korea.

Whether the education system is the main factor in this is unclear. However, rote memorization based exams may disincentivize students from exploring outside the fixed curriculum – after all, extra knowledge does not beget results.

There's a lot to be said about the interpretation of data because perhaps the above is just reflecting Japanese humbleness. Nonetheless, the margins between countries suggest that in the field of non-cognitive skills the field is rather mixed when you add the above to perseverance.

Curriculum

Moving on to the education system proper, it's also worth looking at what cognitive skills – and skill sets – the education system imparts. While Koichi stresses that non-cognitive skills play the largest part in a person's success I think it's also important to also stress that cognitive skills play a significant role as well. For example, a study by Heckman, Stixud and Urzua in the US (accessible here) suggests that both cognitive and non-cognitive skills play heavy roles in a person's wages.

As Koichi did argue, non-cognitive skills do tend to lead to cognitive skills, which are important for future successes. Non-cognitive may be the "origin" of my success – working harder at math may improve my math skills enough to qualify me to be an accountant in the future – but without those cognitive skills eventually developing I could not have been an accountant.

Therefore, the cognitive skills taught in an education system are important too. Japan has clear successes in literacy and mathematical ability but there are some drawbacks to the Japanese system as well. These include:

Foreign language skills including English:

'Nuff said. This can be an entire article by itself. Despite all of the years spent studying English, the average Japanese person is nearly helpless when put in an English-speaking-related situation.

Presentation Skills:

Actually a mix of cognitive and non-cognitive skills (likeability etc). Not very well taught at all. There's no data on this but a majority of my classmates say that the first time they've ever done a PowerPoint presentation was in University. Body-language, reading-from-a-script and extremely wordy PowerPoints are still very common from my experience.

Written expression:

Sumitani and Robert-Sanborn have written an interesting essay here (In Japanese) about the role of essay-writing in education and society. Anyways, essay-writing is not emphasized greatly at the pre-university level given that the University Entrance Examination (センター 試験; 2013 sample can be found here) have no essay based component and are entirely multiple choice. Individual universities may choose to add essay-components in their additional secondary entrance examinations though.

IT education:

Perhaps a surprise? The PIAAC survey published in 2013 noted that while Japan as a whole scores average among surveyed countries in terms of "problem solving in technology rich environments", the group aged 16 – 24 years old performed below average compared to the youth of other countries. IT education is a subject in school so it's not as if they have zero technology education. My view is that the lack of personal research projects, computer presentations etc in other subjects inhibit Japanese youth in developing these skills.

So as with the non-cognitive segment, the cognitive skills segment for the Japanese proves to be mixed in terms of its limitations and successes (reading, writing, numeracy). As you can see, the Japanese education system's effectiveness really gets hit hard when you step outside the bounds of "facts that you can learn." Creativity, the ability to take those facts and apply them to something else (language speaking, presentations, written expression, etc) are all what I'd consider weak points of the Japanese education system.

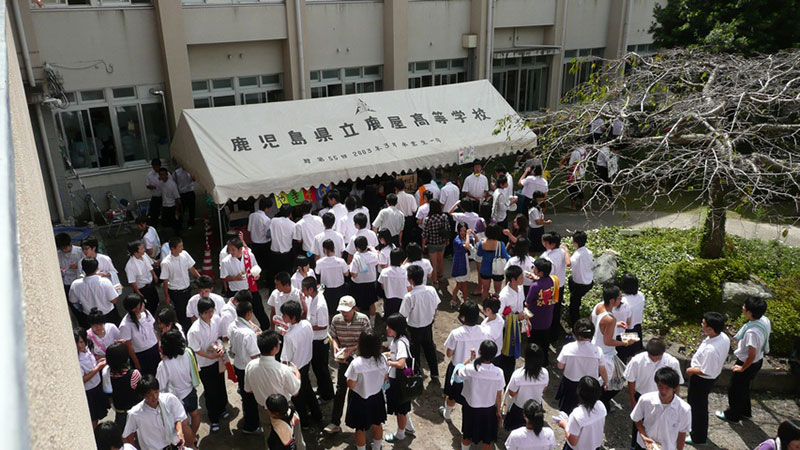

How The Japanese View Their Own Education System

But perhaps one linked (but important) topic that needs to be touched on is how the Japanese evaluate their own education system.

The first thing that needs to be said is that in Japan now, there's a lot of pessimism about the future. Part of this pessimism is a tendency to blame and criticize the young. Perhaps the pessimism is justified by genuine issues among Japanese youth but then again the general pessimism may tint the evaluation of the youth by the people living in Japan (including me as a resident).

We don't know how strong the effect of each direction is but any self-evaluative surveys must be qualified by this possible bias. However, one question which I expect many Japanese to ask is: if our education is so good, why is our economy still doing so badly?

There is in general a perception that Japan's academic standards have been declining. Nakai has written a very complete article here about the debate and its history. Furthermore, there was a survey published in 2004 showing that employers were by and large very dissatisfied with the skills of high-school and university graduates. Given that the Japanese economy has not experienced any significant improvement so far I doubt if the appraisal today would be significantly different.

Given this, it probably would seem odd to many Japanese to hear their education system described in such a positive light. In fact if it were not for widespread dissatisfaction with or fears about the quality of education in Japan, the government would probably not have announced wide ranging reforms last year.

Given The Above…

I really have to caution people about treating Japan, or any other Asian country, as shining beacons of academic excellence. We all have our problems and unless you know a lot about the other side, it's very easy to fall into "grass is greener on the other side" pitfalls.

So while we may laugh at articles from the Onion titled Chinese third graders falling behind US high school students in Math, Science, let me just end by saying that there's actually a lot that Asians (at least those that I know) admire about Western education too. Like the high emphasis on debate, discussion and communicative skills, for example.

But not the math, oh no no no certainly not the math standard. But that's for another article someday.