Japanese (sparkling water) beer is the medicine that helps the salaryman endure their boss' off pitch karaoke during the frequent work parties. It is the refreshing, crisp drink that gets the common Japanese red-faced in only half a pint. Those who have had the pleasure of drinking the more popular "dry" variety can probably describe them as having a distinct mute flavor and aroma, yet sharp delivery. Definitely a departure of the pale lager's typical hoppy bitterness.

But has Japanese beer always been so light and easily drinkable? Nope.

Before the bubble, Japan's beer market was populated by the more typical pale lager with the bitter note flavor profile. The similar flavors that the Japanese was introduced with when the Dutch opened beer halls in the 17th century to accommodate the sailors running the trade routes. Why the transition to a lighter tasting beer? It's the result of one of the many beer wars among Japan's four major breweries that began in the 1960s.

In order to understand the Dry War, some context is needed. So grab a Super Dry, or the equally appealing, a Kirin Ichiban and kick back.

Events leading up to the Dry War

Modified Source: Tofugu / Original Photo Source: Asahi Prior to the Dry Wars that began in 1985, Japan's beer industry was made up of an oligopoly of beer brewers: Kirin, Asahi, Sapporo, and Suntory.

Kirin dominated the market after World War II and had a 61% share between the mid 70s and up until '85. Sapporo was a distant second with its 20%-25% variable share, followed by Asahi's 9%-13% and Suntory's 5%-9%.

Asahi and Sapporo used to be one entity known as Dai Nippon Brewery. Due to postwar anti-monopoly laws set out to dissolve the zaibatsus, the clique was split into the two we are familiar with today: Asahi Brewery and Nippon Brewery (shortly renamed to Sapporo Brewery).

Because of the high entry barriers in advertising costs, distribution, and government regulations, the four breweries dominated the market. Prior to 1985 and after World War II, only two firms have attempted entry into the beer market. Takara, a distillery, entered in 1957, but shortly withdrew eleven years later. The other was Suntory, whom entered in 1963 and still remains despite having a weak presence in the beer market.

(Ok. Not exactly a commercial dating before the 1980s. But it has the Yellow Magic Orchestra!! Ryuichi Sakamoto!)

Government regulations at the time favored nonprice competition in the beer industry, meaning a stable and reliable source of taxes for the government. With no option of competing in price, the available points of engagement for the breweries to compete with their competitors were product quality, advertising, and control & development of distribution channels. This favored heavily with Kirin since it had the resources to invest heavy-handily into the three groups. Kirin also established a strong reputation among the consumer, having it's name synonymous with beer.

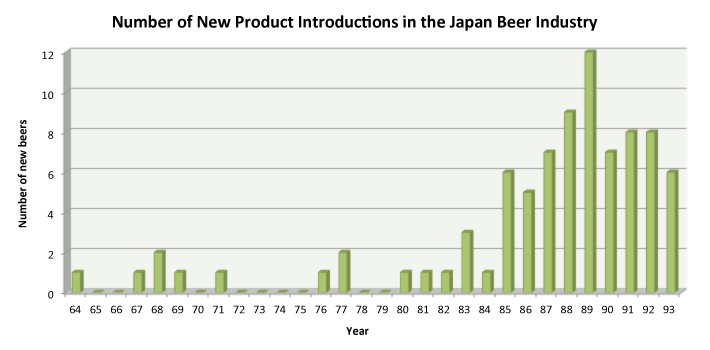

The bottom trifecta's best chance of gaining any marketshare was to invest in product development and innovation. This led to many mini wars.

Up until 1964, Japanese canned and bottled beer went through a heat pasteurization process. Interest in draft beers grew in the nation, which led to R&D investments into bottling "draft" beers. What is known as the draft wars came into fruition. Suntory marketed the first pure draft beer in 1967, which utilized a microfilter developed by NASA. Asahi followed with their pure draft variant in 1968, followed by Sapporo in 1977, and Kirin in 1981. Shortly after its introduction, draft beers accounted for 41% of the market share in 1985. However, the total marketshare in the beer industry between the four groups have not change significantly.

The next notable war was dubbed the container wars in the late 1970s. Each company attempted to differentiate themselves by coming up with various bottle and can designs. Asahi and Suntory started the fight, then Sapporo and Kirin joined soon after. Just like the draft wars, the war fizzled out in the early 1980s with no change in marketshare.

From these two wars, a certain pattern became clear. Whenever one of the lesser breweries introduce a new innovation into the market, it was quickly imitated. If the trend was any threat to Kirin, the brewery would use its overwhelming resources to suppress their competitors growth and the market would be back to its original balance.

Why didn't Kirin just come out and crush the competition with their own innovations? Why were they so slow to react when a new innovation into the market comes along? Anti-monopoly laws. Already a dominant force in the market, Kirin tried not to be heavy-handed in their reactions to avoid being in the spotlight of anti-monopoly whistle blowers. The bottom three also learned that any form of aggression must be handled carefully, otherwise Kirin will step in and subdue any of their attempts.

Then came the mid-1980s, the decade where the Japanese economy was at the top of the world and the center of attention.

Wave of new beer products

The 1980s brought about a new wave of changes in the Japanese consumer and the market environment.

- Changes in competition - Foreign brands of beer had entered the market at full force and marketed at well below cost when compared to the domestic brands (due to the favorable exchange rate at the time).

- Changes in distribution - Due to more singles and younger couples living in small urban apartments, the option of buying larges cases of beer was forgone for buying individual cans from vending machines, convenient stores, and the market. This opened up the option for the consumer to explore different brands and types of beers.

- Demographic trends - The dominate consumer of beers has now transitioned to those born postwar, a generation that has acquired more modern tastes and are looking to distinguish themselves from the older generation

- Dietary changes - Japanese diet had grown more richer. To complement the richer diet, a lighter-tasting beer is more suited. Oil and fats purchased per household nearly doubled, while sugar and salt consumption drop by half between 1965 and 1985.

- Social change - More and more females, especially the younger trend setters, began drinking beers. Their taste was found to be more towards the lighter spectrum.

- Economic change - Income for the typical Japanese has rised dramatically. With the increased income, self-expression replaced homogeny. Beer became less of a commodity.

From the list of changes, it became clear that the consumers were demanding for new tastes and variety.

Three out of the four breweries took note of these changes and started introducing a variety of niche beer products produced in low volumes.

Producing niche products in small volumes didn't affect the marketshare landscape. And one of the breweries recognized this.

Asahi in the 1980s had fallen in a rough patch. Due to poor profit performances, decreasing marketshare, and forcing early retirements for senior employees, the company was forced to come up with a new bold product strategy.

Instead of making niche products that would offer small marginal returns, Asahi's product researchers knew they needed to create a new flagship product. Analyzing the environmental changes, it was hypothesized that beer taste preferences were related to dietary makeup. Before the changes, Kirin's flagship lager dominated the market due to it's bitterness complementing well with the lighter Japanese diet. Since the Japanese diet has shifted, the consumer taste in beers was ready for a shift as well.

To test this hypothesis, a survey was conducted in 1984 and it was found that Japanese beer drinkers were looking for two qualities: 濃こく(koku), rich taste, and 切きれ (kire), sharp and refreshing. Conventional wisdom at the time suggested that you can have one or the other, but not both.

That didn't stop Asahi, though.

Asahi R&D was tasked to create a beer that was both more koku in taste than the Kirin Lager and more kire than the most kire beer out the in the market, Sapporo's Black Label.

And they delivered. The introduction of the new koku-kire beer in 1986 helped increased Asahi's sales by 12%.

With the newfound success, Asahi knew they were on the right track. Asahi researchers then hypothesized that the market was moving further and further away from koku and more towards kire. This hypothesis resulted in the birth of Asahi's Super Dry.

Modified Source: Tofugu / Original Photo Source: Asahi On the date of its release in 1987, the dry lager immediately became the company's top seller. It was so popular that Asahi prohibited its employees from purchasing the product in order to save it for the customers. Kirin, Sapporo, and Suntory brushed it off as a fad and thusly didn't immediately produce a rival product.

This was a big mistake.

13.5 million cases of Super Dry was sold in 1987, which led to a 33% jump in sales. By 1989, Asahi's marketshare increased to 25%, overtaking the second marketshare leader, Sapporo. The dry brew cannibalized into Kirin's market share, which dropped by 11%. By the end of 1989, Super Dry accounted for 20% of all beers consumed in Japan. This success allowed Asahi establish important new distribution channels and sales outlets.

By the time the other breweries wisened up, Asahi solidified itself as the king of dry beers.

Aftermath

How did it play out for Asahi and the others since the introduction of Super Dry? Many attempts of introducing the next beer or imitating the dry taste fell flat. By 1993, all attempts of copying the dry beer was abandoned, conceding the dry beer segment entirely to Asahi. As of 2010, Asahi held the number one marketshare spot with 38%, while the runner-up, Kirin, is not far behind with 37% 2.

All thanks to the (watery) light, cool, sharp, refreshing taste of Super Dry.

-

Craig, T., (1996). The Japanese Beer Wars: Initiating and Responding to Hypercompetition in New Product Development. Organization Science, Vol. 7, No. 3. Retrieved January 5, 2012. ↩

-

Fujimura, N., (January 16, 2011). Asahi Reclaims Lead in Japan's Beer Sales Over Kirin as Market Declines. Bloomberg, Retrieved May 1, 2012. ↩